Young, geeky and black in Memphis

- Published

Facebook has more than one billion users and hires more than 1,000 people each year in the US. But in 2013, just one of these new employees was a black woman. Fewer than 2% of employees at Google, Twitter and Facebook are black. The tech industry is trying to tackle this diversity problem - but efforts are also being made at the grass-roots level.

If you've ever read a profile of a successful US tech company, you've probably read a story like this: white men meet while studying at a prestigious university and start a business out of a garage. HP, Apple, Google, Amazon - all started by white men in garages. It's a story that inspires young tech entrepreneurs to follow in their path.

But in places like Memphis, where two-thirds of the population is African-American, there are few role models to show young black girls that a successful career in tech is possible.

"White guy, Oxford shirt, black slacks," recalls Audrey Jones. "The IBM uniform. That's what I thought a smart person looked like, not like me or anybody else that I knew."

Audrey grew up in South Memphis, one of the city's poor, African-American neighbourhoods. Her mother struggled with drug addiction and died when Audrey was in her teens.

"That's the tragedy of being in this neighbourhood," she says. "You can easily, easily get sucked into the wrong lifestyle, and it's difficult to get out."

Audrey could easily have been trapped in poverty herself. She married young, had a child, got divorced, and ended up working in a call centre.

But then, back when MySpace was in its heyday, she wanted to change the look of her MySpace page.

"I didn't want to pay for those layouts," she recalls. "They were 99 cents, I was a single mom, I didn't want to pay for that."

So she found the code in a book and did it herself. She says she thought nothing of it, until a colleague saw what she'd done and encouraged her to speak with the company's IT guys.

"A light bulb went on," Audrey remembers. She continued to soak up information and teach herself, and eventually landed an IT job with a big company.

"It was crazy because it was night and day," she says. She'd gone from barely getting by to making good money.

Her own journey has inspired Audrey to help other girls from similar backgrounds make it into coding and technology.

She recently co-founded Code Crew, an organisation that runs summer camps and after-school coding classes for children from under-privileged backgrounds.

"I can't change everybody at once," Audrey says. "But if I can work for a girl maybe that will ignite a fire and give her the inspiration to change."

Memphis and its suburbs are the poorest metro area in America, and among the most economically segregated. Two-thirds of the population are black, and poverty affects them disproportionately.

This year's season features two weeks of inspirational stories about the BBC's 100 Women and others who are defying stereotypes around the world.

The digital divide is stark here too. Memphis has one of the lowest rates of internet access in US - a third of residents have no internet access at all.

But the city is also home to a growing number of grass-roots groups like Code Crew working with young women and minorities to get them interested in so-called Stem fields - science, technology, engineering and maths.

Karen Farrell-Shikuku, who has spent 17 years in the tech industry, is used to being the sole African-American woman in the room.

"I've actually gone to quite a few conferences. They have over 10,000 attendees," she says. "So you imagine walking around there and you see no-one that looks like you, you see no-one with a dress."

I meet Karen in a lecture theatre at the University of Memphis. It's a Saturday morning, and the normal academic calm of the place has been shattered by a group of 50 or so African-American girls aged between 10 to 16.

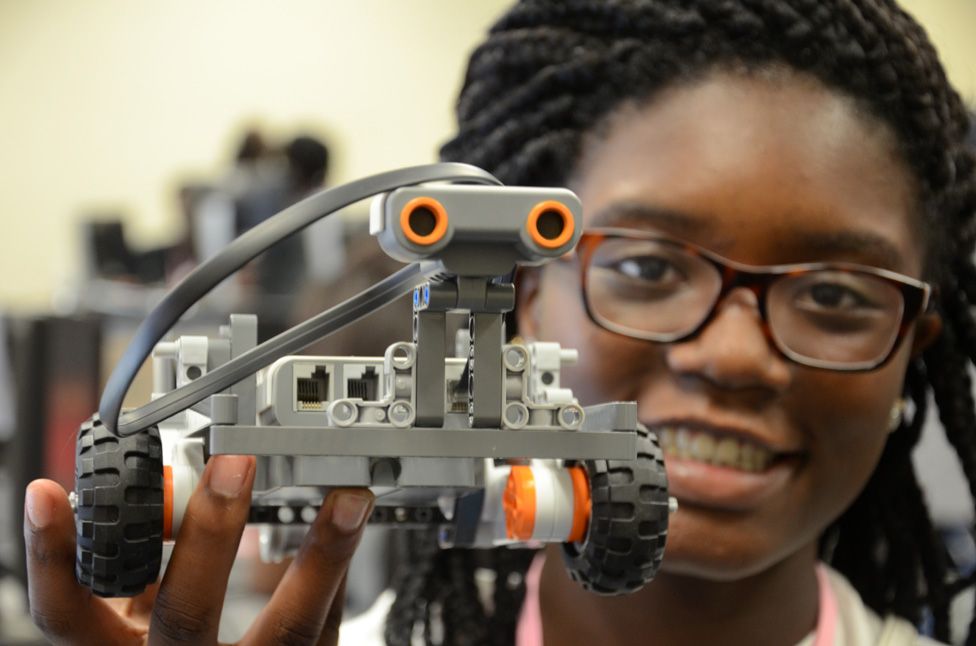

There's clapping, rapping, and an energetic, unpretentious atmosphere as Karen and a team of volunteers teach the girls how to build and programme small robots.

The day is organised by the Memphis chapter of Black Girls Code, which Karen helps run. The national organisation was started in 2011 to encourage more minority women into Stem careers.

"It's about getting these young ladies exposed to what technology is, and showing them it is nothing that only this elite group of super-smart people can do," says Karen. "No. It's something that's attainable by anyone and everyone."

Women currently make up just under half of the US workforce - but only a quarter of the computing workforce. It wasn't always this way. Many early coding pioneers were women, and in the mid-1980s, 37% of computer science majors were female. But by 2012 that number had halved.

"People already in a major can be exclusive to outsiders," says Top Malasri, an instructor in the computer science department at the University of Memphis.

"It's a traditional boys' club, not very welcoming of other people, and the more diversity we can bring into the the field the better that situation is going to get, hopefully."

The girls soon have their robots scooting across the floor, smashing into the walls, and tackling obstacle courses and more advanced challenges. If excitement, decibels and high fives are any measure, the workshop is a big success.

"Right now I'd probably just be waking up, and going to the mall or the movies," says 13-year-old Anaya Neal, as pizza arrives for lunch. "I didn't even know I liked programming."

The next day, I drive to one of Memphis' predominantly African-American suburbs, where Anaya Neal lives with her mother. On the way, I pass cracked and overgrown sidewalks, empty lots, and houses boarded-up and falling down.

The Neals' home sits behind a well-kept lawn. In the living room Anaya's academic achievement certificates take pride of place.

"I want better for her," says Anaya's mum Elicia. "I am invested in her future, if I don't do it no-one will. I will not allow her to become a statistic."

Elicia has been the driving force getting Anaya into coding. She's taken a year off from her job as a medical support worker just to supervise Anaya's schooling, and says that's what it takes in this neighbourhood.

"It's changed since I was a kid," she says. "The crime rate is pretty high, there's drugs, gangs, prostitution. I've seen girls as young as Anaya's age, 13, pregnant."

Elicia's ambition for her child seems to have sparked a genuine interest in coding. It appeals to Anaya's problem-solving side.

"Coding is a good way to focus your brain," Anaya tells me.

"I like to struggle through stuff, make my mind work. I do not like to get help."

Like most teens, she's glued to her phone most of the time, communicating with friends on apps like Snapchat, Whatsapp, Kik and Instagram.

But she also tells me that some apps and games don't feel like they're made for her - for example where the only character she can play is white, or where black characters are so dark they look burnt, as she puts it.

"That's really rude because we're not burnt, we're brown," she says. "I was like, 'I don't want to play this any more.'"

Anaya dreams of starting her own business, possibly in the technology world. And mum Elicia feels that even if she doesn't become a coder, the exposure to technology is essential.

"Technology is everywhere," she says. "You can't do without it."

Across the US, the big tech companies are making moves to address diversity issues - hiring diversity officers, supporting organisations like Black Girls Code, and funding programmes to promote STEM education for women and minorities.

But progress is proving slow. In 2014 Facebook hired 18 black women in the US - better than the year before, but still just 1.4% of their overall hires.

Groups like Code Crew and Black Girls Code are reaching hundreds of children, and have plans to expand further - making a difference to individuals like Anaya Neal, but not enough to change a whole city like Memphis. So what could really move the needle?

"We have to bring coding back to schools," says Code Crew co-founder Meka Egwuekwe, who, after a successful career in the software industry, found there was a lack of opportunities for his two young daughters to follow a similar path.

In Tennessee and across the US, coding isn't currently a compulsory part of school curriculums. It's not tested, so it's often not taught, especially in more disadvantaged schools where resources are tight.

That's not poverty, that's not ignorance," says Vee Barrett, a volunteer at both Code Crew and Black Girls Code. "That's intentional, systematic prejudice designed to keep you back economically."

The feeling that African-Americans might be missing out on access to the key economic opportunities of the future resonates particularly strongly in Memphis.

It was here that civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr was assassinated in 1968, at the Lorraine Motel which is now home to the National Civil Rights Museum

"We're still about the same thing that Dr King was talking of," says Vee Barrett.

"That's equality."

Teaching coding in the slums of Ghana

As part of the BBC's Young, Geeky and Black series looking at black coders, Bola Mosuro travelled to Ghana to meet women and girls coding there.

Nima is one of the largest and poorest districts in the Ghanaian capital Accra.

But in a first-floor classroom above a local mosque, something remarkable is happening. Groups of girls in brightly coloured hijabs and school uniforms crowd around a few available laptops. This is the Achievers club of Nima, and with the barest of resources, they're teaching these girls coding.

"It's the imams who are becoming a major challenge," says Amadu Mohammed, who helps organise the classes. "According to them all a girl needs to do is be obedient, learn Koran, pray, submit to husband."

But coding is giving the girls the opportunity to express themselves, on websites and blogs.

Listen to the Programme on the BBC World Service, on Tuesday 1 December from 00:30, or catch up afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.