Will Trump or Biden be better for Asean countries amid US-China stand-off?

- Under Biden, US foreign policy will not ‘snap back’ to that of the Obama era, and its hardline strategy towards China will remain largely unchanged

- Whichever candidate wins, Asean countries will find themselves at the centre of an intensifying Sino-US rivalry, especially over the South China Sea

If Trump is re-elected for a second term he is likely to pursue many of the same policies, domestically and internationally. The Republican National Committee opted not to publish a 2020 party platform, instead deciding to persist with the 2016 party platform. A second term is also likely to be characterised by the same rancour and unpredictability that marked his first term in office.

Unless Democratic challenger Joe Biden wins an overwhelming majority of the states, the popular vote and the electoral college, Trump could legally challenge the result, leading to political uncertainty and possibly violent protests for several months. Such a scenario would likely be more destabilising than the aftermath of the 2000 contested presidential election.

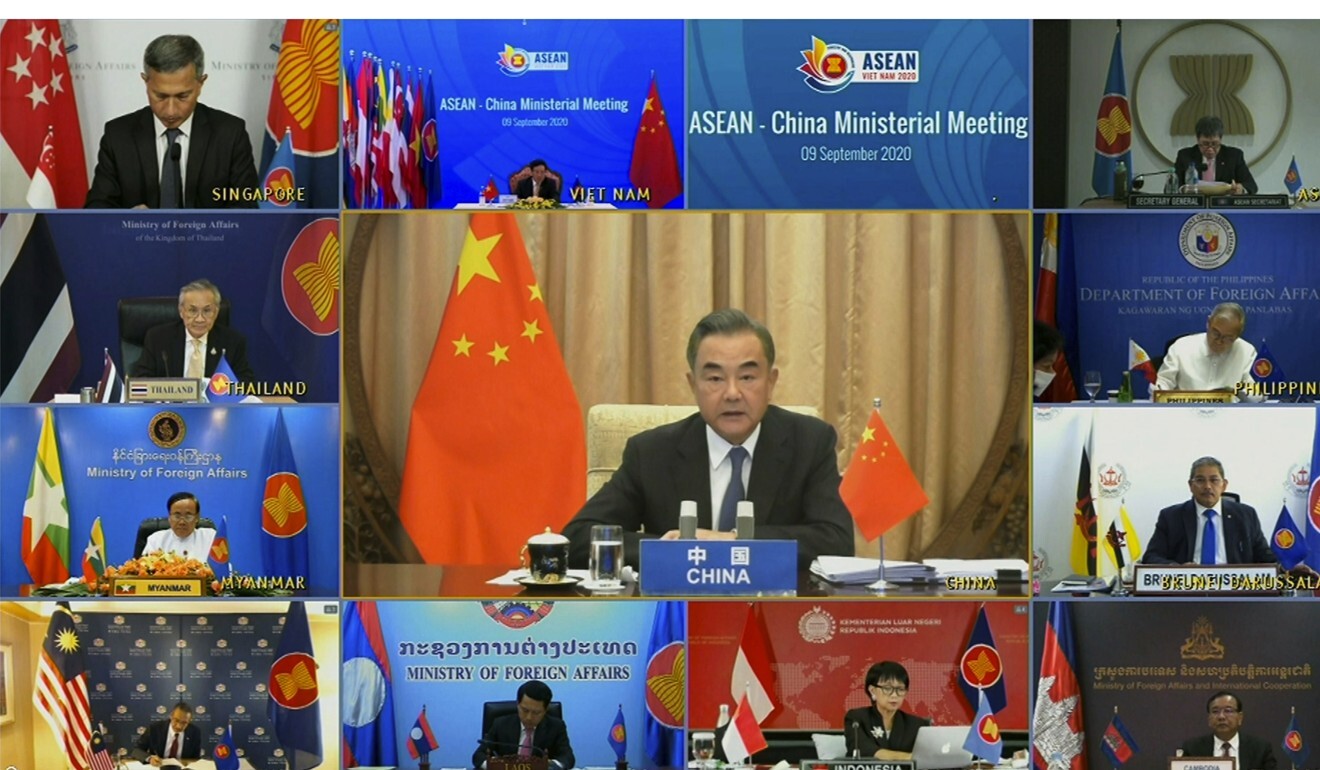

Beijing’s South China Sea talks with Asean worse off than it lets on: experts

If Biden does take office in January 2021, his administration is likely to be less unpredictable and more consistent than his predecessor, with fewer high-level resignations and fewer posts left unfilled. Under Biden, US foreign policy will not “snap back” to that of the Obama era, though his administration may place a greater emphasis on strengthening America’s relations with allies and international organisations, which have frayed under Trump. America’s more hardline strategy towards China will remain largely unchanged under Biden. The atmospherics of Sino-US relations could improve slightly and the tactics used by Washington to pursue this rivalry may also change.

MIXED RECORD

Compared with the Obama administration, Trump has paid little attention to Asean

Except for the Philippines, Southeast Asian states have not responded positively to the Trump administration’s push for new bilateral trade deals. Two years after planned US-Philippine exploratory talks were announced, details on them remain sparse.

The Trump administration’s more aggressive approach to China’s economic policies long deemed unfair by the United States, and China’s responses to these Trump administration punitive actions, will have more effect on Southeast Asian economies. The 2020 ISEAS State of Southeast Asia survey report shows that 64 per cent of those surveyed expect these knock-on effects to be bad for the region.

DEFENCE ENGAGEMENT

Since Trump took office, US-Thai defence relations have been normalised, while security ties with Vietnam, Singapore and Indonesia have been further consolidated. Because of President Duterte’s pro-China and anti-American leanings, the US-Philippine alliance has come under strain, though the country’s national security establishment has been largely successful in preserving defence ties with America. Most significantly, in June 2020 the Duterte administration suspended for 6 to 12 months its February decision to terminate the 1998 Visiting Forces Agreement.

South China Sea: Malaysia rejects Philippines’ Sabah claim

The Trump administration’s tougher South China Sea policy has generally been welcomed by the Southeast Asian claimants, especially its support for their sovereign rights in their exclusive economic zones. However, there is some concern that a US-China military confrontation in the area could embroil the region in an unwanted crisis.

Overall, America’s image in Southeast Asia has suffered over the past four years. In its annual survey of regional elite opinions in January 2020, the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found that 49.7 per cent had little or no confidence that the United States would “do the right thing” internationally, while 77 per cent believed America’s engagement with Southeast Asia had declined since Trump took office. Three-fifths agreed that a change of leadership in the November 2020 US presidential election would increase their confidence in America’s position in the region.

A BIDEN ADMINISTRATION AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Although US party platforms are not meant to be concrete pledges of action, they do give a general indication of the policy directions the administration will take. The Democratic Party platform makes a number of promises on foreign policy, such as standing up to China over intellectual policy theft and industrial cyber espionage.

Close Uygur camps, dial back ‘wolf warriors’: how China can win support

America’s South China Sea policy under Biden will remain unchanged. We can anticipate an increased tempo of exercises with allies and partners, presence missions and FONOPs. The United States will continue to provide capacity-building support for the Southeast Asian claimants.

SOUTHEAST ASIAN PERSPECTIVES

Is Beijing trying to exhaust Taiwan’s air force?

Southeast Asian states will be less enthusiastic about a Biden administration if it adopts a strong rhetorical stand on promoting democracy and human rights, as previous Democratic administrations have done. These concerns would be aggravated if a strong proponent of human rights is appointed as secretary of state.

Concerns about America’s relative decline against China were prevalent in Southeast Asia before Donald Trump’s surprise 2016 presidential victory. Fears about US disengagement from the region and China’s more aggressive use of its growing power over the last four years have aggravated these significantly. A second Trump administration or a first Biden administration will find it hard to address these worries but will need to gain greater regional support for US policies on China and efforts to reassert US leadership.

Ian Storey is Senior Fellow and Malcolm Cook is Visiting Senior Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. This article first appeared in the publication ISEAS Perspective 2020/112, titled The Trump Administration and Southeast Asia: Half-time or Game Over?