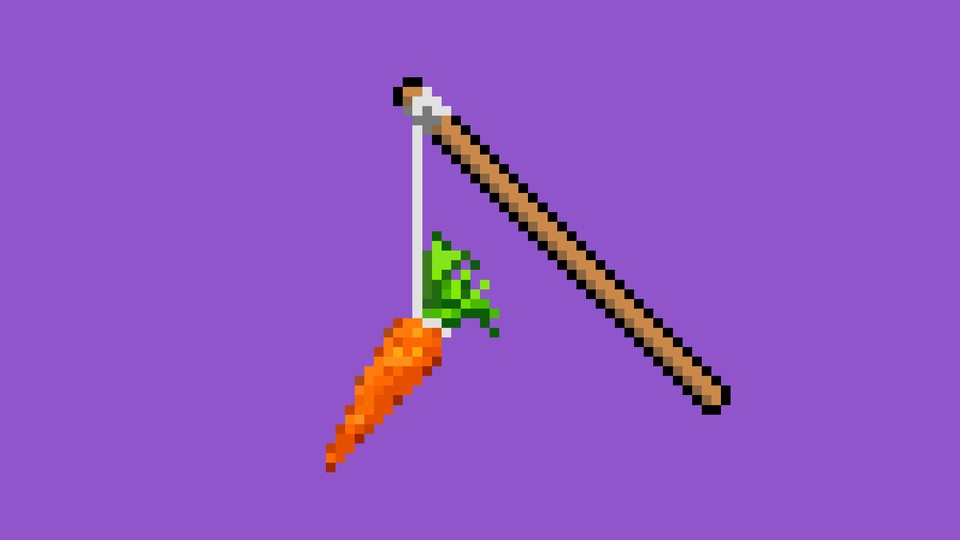

ChatGPT’s FarmVille Moment

The immediate future of generative AI looks a bit like Facebook’s past.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

Updated at 2:49 p.m. ET on January 17, 2024

ChatGPT has certainly captured the world’s imagination since its release at the end of 2022. But in day-to-day life, it is still a relatively niche product—a curiosity that leads people to ask questions that begin “Have you tried … ?” or “What do you think about … ?” Its maker, OpenAI, has a much more expansive vision. Its aim is seemingly to completely remake how people use the internet.

For that to happen, the bot needs to be more than a conversation starter: It has to be a functioning business. The company’s launch of the new GPT Store on Wednesday was an ambitious step in that direction. Initially announced two months ago, the GPT Store allows the product’s business and “ChatGPT Plus” users—those paying $20 a month for an upgraded version of the service—to create, share, and interact with customized AI agents (called GPTs) that are tailored to specific tasks. The company claims that its users have built more than 3 million of these custom bots since they were granted the ability to do so in November, in preparation for this launch.

When OpenAI debuted the store, it highlighted six specific GPTs: A bot that will recommend hiking and biking trails, one that synthesizes and summarizes academic papers for you, a coding tutor from Khan Academy, a presentation-design assistant from Canva, an AI that recommends new books to read, and an AI math-and-science tutor. The immediate aim of these entries and others is presumably to persuade users to pay that monthly subscription fee. But the broader project here is more ambitious. OpenAI is trying to turn ChatGPT into a platform.

It’s deeply reminiscent of Facebook circa 2007. OpenAI has begun the hunt for its FarmVille.

2007 was the year when Facebook rolled out the Facebook Platform, which allowed developers to create their own applications that would run within the company’s “walled garden”—a term for a tech platform’s private ecosystem. Before then, Facebook was still just MySpace for college kids. You could visit friends’ pages and “poke” one another. But there wasn’t much else you could actually do on the site. The idea that Facebook would eventually swallow the entire news business or be described by this magazine as a “Doomsday Machine” was unfathomable. Facebook was still a toy.

Most of what the developer platform initially enabled were silly games. But those games expanded the range of what the social network was good for. They gave Facebook a built-in advantage over competing sites and made the platform more addictive. In 2008, Facebook overtook its rival MySpace in unique visitors, and by 2009, time spent on the site had skyrocketed. This was still in the early days, back when Facebook was a “social-network site” rather than part of the now-ubiquitous “social media.”

FarmVille broke through in 2009 as the developer platform’s clearest success. It was a simple social game, impossible to describe today in ways that make sense of its appeal. In FarmVille, you were a farmer. Click a button, plant a crop. Click the button again, milk a cow. Send requests to your Facebook friends for help tending your farm. They clicked along, making your farm bigger and filling one another’s Facebook feeds with FarmVille activity updates. Sell your crops for in-game currency to buy in-game luxury goods. Or, if you were impatient, you could convert real dollars into in-game currency and buy that FarmVille villa you craved. It was, in many ways, the forerunner to the mobile games that would flood the Apple and Android app stores in the decade that followed. FarmVille tapped into Facebook’s ethos of networked participation and fit Facebook’s algorithmic News Feed like a glove. Zynga, the game’s developer, reached a multibillion-dollar valuation based entirely on its ability to create games within platforms that people could not stop playing.

These were the transition years, when niche social networking expanded into social media. Facebook didn’t make FarmVille: Rather, during this crucial chunk of time, FarmVille made Facebook. OpenAI is at a similar juncture today. 2023 was supposed to be the year of the ChatGPT revolution. The AI doomers and AI bloomers were everywhere, yet viewed with a bit of critical distance, the technology is still little more than a toy.

Sure, the first time you have a conversation with the chatbot or ask it to rewrite your grocery list in the form of a Shakespearean sonnet, the result can be astonishing. But the novelty wears off. ChatGPT is not omniscient. It has neither personality nor perspective. How often do you actually need a computer to produce some fake Shakespeare for you, anyway?

Plenty of people have tried OpenAI’s products, and the company boasts that it has 100 million weekly users. But those statistics mask the question that the GPT Store is designed to answer: What exactly are most users supposed to do with it? What are the uses that would eventually be worth paying for? A little more than a year in, it seems as though devout ChatGPT users generally fall into one of four buckets. First, there is the subset who were already using machine learning in their jobs. Generative-AI products such as ChatGPT do the job better than the older products that came out of the Big Data hype cycle a decade ago. These are the people who remain the most genuinely excited about the revolutionary potential of the technology. But their group is also pretty narrow.

Then there are students using ChatGPT to cheat on tests or for help with homework. ChatGPT usage declined in the summer, when kids were out of school, surprising approximately no one. There are also the managers who spent the past year or so using generative AI to cut costs while sacrificing quality, particularly in the media industry. Finally, there are the hobbyists and hype bros, people who just like to play around with ChatGPT because it feels like the future to them, or because they think they smell profit. The same type of Twitter accounts that spent 2021 hawking NFTs—and 2022 crowing about the metaverse—are now all-in on prompt engineering.

The problem for OpenAI is that the majority of ChatGPT’s 100 million weekly users rely on the free product. Meanwhile, the company’s CEO, Sam Altman, has described the cost of keeping ChatGPT’s underlying engine running as “eye-watering.” In the short term, the more outside developers that OpenAI attracts, the more tailored GPTs offering trail recommendations and science tips it hosts, the greater the chance that those free users choose to sign up as paying subscribers. The company did not comment on its plans when reached for this article—a spokesperson only pointed to a November blog post about the GPT Store—but the medium-term ambition seems identical to Facebook’s in 2007. OpenAI can take the next step in remaking the internet user experience only if it can come up with a better answer to the question “Okay, but what else will people use it for?”

Altman, like Mark Zuckerberg before him, has imperial ambitions. Zuckerberg aimed to colonize the internet, remaking it in Facebook’s image. He largely succeeded. Altman’s ambitions are even larger. And so, like Facebook, his company has reached the point where it is hoping someone else can develop the next wave of use cases. He’s attempting to turn it into a platform.

Whether this will work is unclear. OpenAI was rocked by internal strife immediately after Altman announced the GPT Store in November. ChatGPT is the best-known generative-AI tool, but it has numerous competitors. OpenAI is also going to be battling major lawsuits throughout 2024, which won’t help matters.

When Facebook invited developers to build tools on top of the Facebook platform in 2007, the company was experiencing fantastical growth and had seemingly limitless revenue potential. OpenAI is inviting developers in 2024 to build tools that could themselves become lawsuit targets. OpenAI has created a moderation system to weed out GPTs that violate its brand guidelines and usage policies, but there is a pretty wide gap between OpenAI’s position on acceptable GPT uses and the position of potential litigants. And meanwhile, the direct revenue potential for developers is still an aspirational promise, to be revisited sometime in the first quarter.

Still, for OpenAI, the purpose of the new GPT Store seems clear. It worked for Zuckerberg and Facebook. The 2010s became the Facebook Decade, for better and for worse, in part because Zuckerberg courted third-party developers and used the products of their labor to make his own product stickier. Altman and OpenAI have similar ambitions, and they won’t get there on their own (or with an AI-powered Microsoft Clippy 2.0).

ChatGPT needs its FarmVille. OpenAI is betting that some unknown developer, somewhere, will come up with it.

This article originally mischaracterized the duration of Zynga's multibillion-dollar valuation.