By: Thomas Kim

Hello there!

My name is Thomas, and I’m a rising senior majoring in International Relations with a minor in Environmental Studies. Welcome to the June 4th edition of What and Where Has Global East Asia: Japan Eaten and Been to Today! On today’s edition, we indulged our taste buds in sushi followed by a personally interesting visit to a Korean school.

After a late night of working on my final paper draft, I woke up, hungry and ready for sushi. I held out, mentally fortifying myself against the thoughts of warm toast and butter in the lobby. In what seems like an eternity later, we finally made it to a revolving sushi restaurant in Shibuya.

Heaven on a Conveyor Belt

Growing up, my grandparents owned a sushi restaurant, so to see my childhood favorite, tamago (egg) sushi, made every bite even more wonderful. The food exploded with flavor, and we spent a blissful hour there, stuffing our faces with wonderful sushi and our eyes with little trains delivering orders across the restaurant.

Tamago sushi

Marinated Salmon sushi

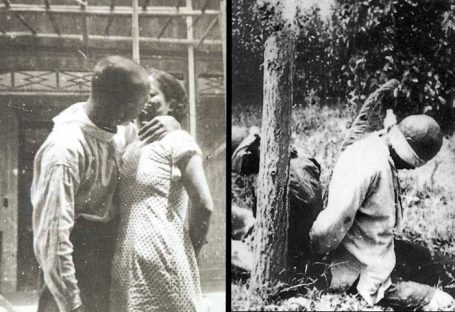

Now to the big event from today: our visit to a Korean school. For some background, the ethnic Korean population in Japan is referred to as the zainichi, and they are historically treated as second-class citizens within Japan, even today. They originally came to Japan for economic opportunity when Korea was a Japanese colony from 1910 to 1945, and now the zainichi population has been here for several generations. Post-World War II, the respective North and South Korean governments began funding schools for the Korean diaspora that continued to live in Japan. Fast forward to the present, and there are only 9 such Korean schools left around Japan. In this time frame, the North Korean government has financially supported many of these schools.

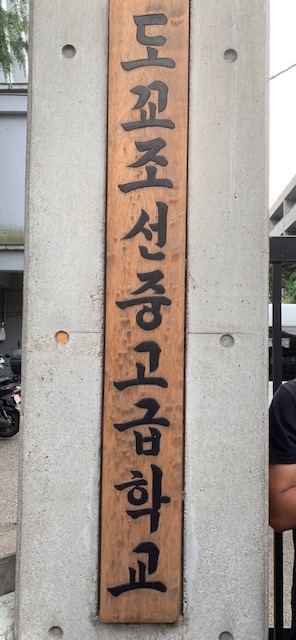

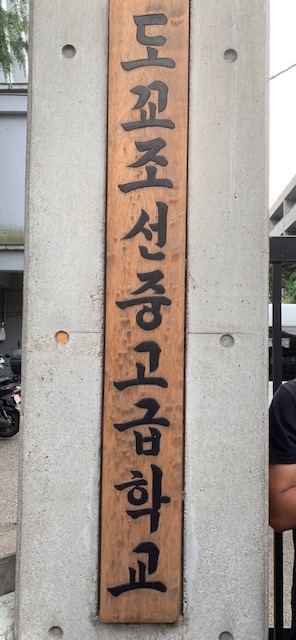

“Tokyo Korean Middle and High School”

Junior High and High School Building

As soon as we walk through the gate, the buildings loomed a little ominously. What could we expect from a school that has received financial support from the North Korean government? Our guide for the visit escorted us into a conference room where he introduced the school and some of its history. The school, Tokyo Korean Middle and High School, is the largest of the 9 Korean schools still in Japan, with about 113 middle school students and 358 high school students. Established on October 5, 1946, the school is celebrating its 73rd anniversary, and most of the students are 3rd or 4th generation zainichi. The students’ nationalities are split between South Korean, North Korean, and Japanese. Our guide mentioned that the school is not geared academically towards funneling its students to college; rather, it seemed like the school wanted to bring athletic prestige as he rattled off the rankings of its various sports teams. Officially, the school has 3 pillars: Intellect, Ethics, and Athletics, and its main goal is to nurture the spirit of Korean culture by learning its language and history. Students are not allowed to use Japanese while at school, except for the younger ones who enter because they would only know Japanese. The students also come from all over Tokyo; some take a 2.5 hour commute because they take it seriously on behalf of their parents’ passion for them to better understand their heritage.

Student art depicting a chima-jeogori

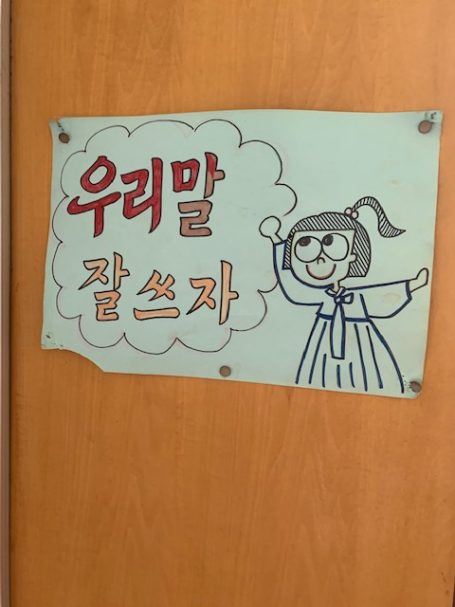

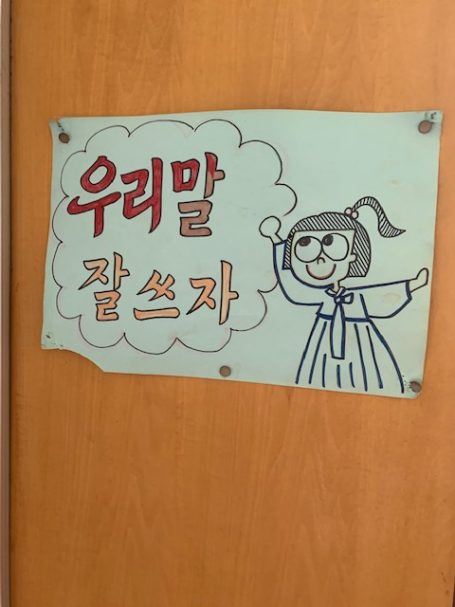

After this general orientation, he took us to various classrooms in the junior high (7th to 9th grade) and high school floors (10th to 12th grade). I do not know what I expected, but I did not expect the students to look at us in the hallway and start smiling and waving at us. It could have been the traditional chima-jeogori that female students were wearing as well as the more elaborate ones that female teachers were wearing. It could have been the portraits of deceased North Korean dictators Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il hanging up at the front of the high school classrooms, or the teachers speaking to their students with a clearly North Korean-dialect. This showed me that even though the teachers themselves are zainichi, the North Korean influence is visible. Interestingly, the junior high classrooms did not have the Kim portraits, and the junior high English classroom was full of laughter and fun. Keith, who wrote about our earlier visit to Miyajima Island, was brought up to the front for the students to practice a conversation with a native English speaker! But as we traveled between classrooms, there were signs everywhere saying the same thing: “우리말”, which basically translates to “Our language”. This refers to their policy of using only Korean at school.

“Let’s use Our Language very well!” aka: USE KOREAN

After touring several classrooms and many waves and smiles later, we returned to the conference room, where our guide brought 8 high school students. The 4 guys and 4 girls split the table, so that they were separated by gender. Then began an awkward attempt at questions and answers from between our two groups, as the language barrier made it so Kyohei, Professor Katada, and our guide had to translate and facilitate conversation. When asked about how they, as zainichi living in Japan, see the North vs South Korea issue, they stated that they feel sad because all three groups of Koreans are all one ethnic group. They have a strong desire for reunification and seek to help play a role in that future. Because my project with my partner, Kenny, focuses on the immigrants’ perspective on living in Japan in the context of discrimination and anti-immigrant sentiment, I asked how they felt about discrimination as zainichi. The captain of the girls’ basketball team said that when they play against Japanese schools, sometimes the Japanese teams are normal and amicable, while others could seem cautious and wary about them because of who they are. She later went on to say that once she revealed her zainichi heritage to her Japanese friends in her youth, some stayed friends with her while others became fearful and hesitant to talk to her after that. She even experienced some bullying from it before she entered the Korean school.

At the end of our visit, we took a group photo and gave our thank you’s for the opportunity to learn about the school and talk to the students. I personally could not articulate how I felt. Even while sitting in the hotel and writing this blog post, I cannot find the best ways to phrase this tension that the visit gave me. As a Korean American, whose grandma fled North Korea when the Korean War broke out, I was honestly never super patriotic about my Korean heritage. This was made worse by living in South Korea for four years, a place I do NOT miss. Yet as a Korean American who had lived in South Korea before, the heavy North Korean influence bothered me. However, what I saw and heard from the guide and students was a completely different worldview. If anything, my perspective of South Korea as the “right” side because of my past and my knowledge of South Korea as a key American ally felt wrong. There was no North vs South. It was all one Korean people, living in an unfortunate and difficult situation to where our people are pitted against one another. These students are roughly half North Korean and half South Korean by geographic heritage, yet they do not feed into that notion. They consider themselves Koreans, albeit Koreans living in Japan. For me, as someone who still struggles with his Korean American identity at times, seeing these Korean Japanese students confirm their identities as simply Korean astounded me. Additionally, seeing Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il’s portraits at the front of the classrooms made me feel conflicted. Some of these students are proud to have North Korean nationalities, but it seemed like they had no idea about the plight of the North Korean people under these past dictators and the current dictator. Yet they are not the cult-like devotee citizens that we in America are taught about.

“Put your hand to your heart!” A message on pride for your Korean heritage

If anything, this visit truly opened my eyes to another worldview. I was raised in a North vs South Korea ideology by my Korean relatives and the American education system. To see another view, one that speaks to the Korean people as a whole, held with such strong conviction shocked me. While I still need some time to consolidate my feelings, identity, and thoughts after this visit, I can say that this visit was one of the most impactful events thus far on my Global East Asia Japan journey, as it shook me to the core, rattling my perception of my identity as an ethnic Korean. But why else do we travel if not to challenge our own preconceptions on identity and worldviews?