Jenni Finlay didn’t tell her father that she was recording their conversations. Her dad, Kent Finlay, had been recently diagnosed with multiple myeloma for the second time when she started recording their phone calls. “I wasn’t thinking about doing a book,” Jenni says. “I just wanted his voice on tape. I would call Dad and say, ‘Hey, tell me your black-eyed peas recipe.’ We would have these conversations like we’d always have, but it was taped. I was sneaky about it. Finally I had a friend who told me this would be a great book.”

After Brian T. Atkinson, author of I’ll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt, agreed to collaborate on the project, Jenni told her father what she’d been up to. “I told Dad, ‘By the way, I’ve been recording you, and I want to do a book.’ Dad was all about it. He said, ‘Well, alright, let’s start setting up meetings.'”

The two met twice a week for the next year and a half, holding court at either Cheatham Street Warehouse, the legendary San Marcos honky-tonk Kent opened in 1974, or at Kent’s home in Martindale along the San Marcos River. “If we were at Cheatham Street, we’d each have a Coke and a pickle,” Jenni says. When the snacks were gone, it was time to take a break.

Those pickle-and-Coke sessions now comprise the first half of Kent Finlay, Dreamer: The Musical Legacy Behind Cheatham Street Warehouse (forthcoming from Texas A&M University Press). Jenni took special care to keep this portion of the book in Kent’s voice, and the result is an easy flowing biography with intimate details chronicling his life, from the cotton fields of his boyhood to his professional career as a songwriter, educator, and businessman.

As the proprietor of Cheatham Street Warehouse, Kent played an immeasurable role in shaping Texas music and helped launch the careers of some of the biggest stars in music history. Black-and-white photographs hanging in the venue today harken to a time when two preteens named Charlie and Will Sexton opened Tuesday nights for a white blues guitarist billed as “Stevie Vaughn.” Other pictures depict Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff sharing the stage during the heyday of the Cosmic Cowboy craze, while two other framed portraits capture the night Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt ignored the city’s club curfew and played to a small, enraptured crowd well past midnight. In the late eighties, songwriters like James McMurtry, Bruce Robison, Hal Ketchum, Terri Hendrix, and Todd Snider honed their craft playing around the wood-burning stove on songwriter’s night. And in more recent years, acts such as Hayes Carll, William Clark Green, Sunny Sweeney, Owen Temple, Jamie Wilson, Adam Carroll, and Randy Rogers developed their artistry under Kent’s careful mentorship.

Many of these artists shared their memories of Cheatham Street and spoke of Kent’s influence on their careers with Atkinson. The second half of the book, “The Players” section, includes remembrances from Texas music veterans Ray Wylie Hubbard, Joe Ely, Marcia Ball, Eric Johnson, Joe “King” Carrasco, as well as venerated songwriters such as Radney Foster, Cody Canada, Robyn Ludwick, Willy Braun, Slaid Cleaves, Walt Wilkins, Scott H. Biram, and Jack Ingram.

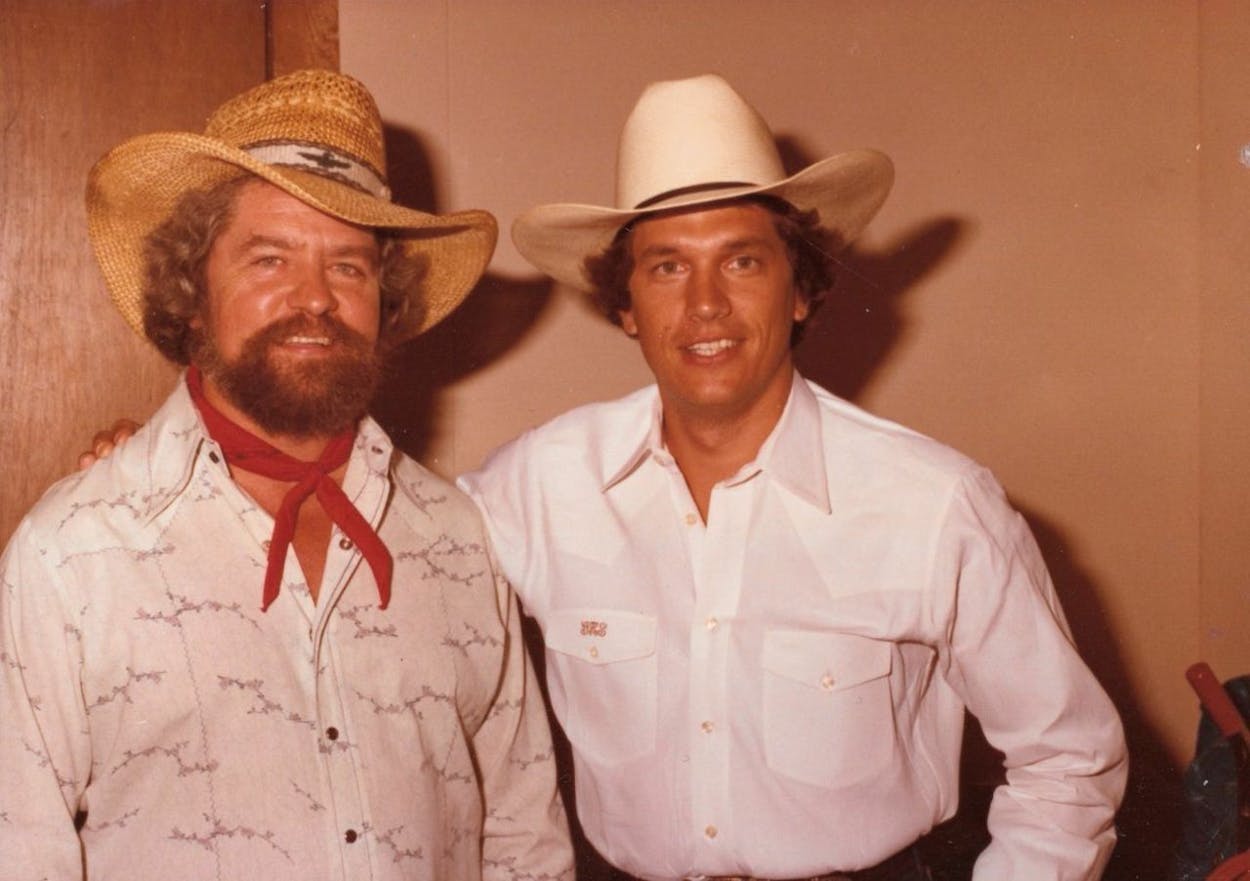

Among these fond—and often funny—recollections is the following excerpt by George Strait, who played his first gig with the Ace in the Hole band on the beer-stained stage at Cheatham. When the King of Broken Hearts won his first Male Vocalist of the Year Award in 1985, Kent broke from his typical modesty to post a handwritten sign outside the door to Cheatham. “I told you so!” it bragged. Signed in large letters underneath: Kent Finlay.

Chapter 25: George Strait

I think it wasn’t until the first time we played at Cheatham Street Warehouse that I met Kent. My impression of him at the time was, This guy’s pretty cool to have such a classic little honky-tonk. I want to be friends with him. I’m sure I was very nervous playing. I don’t remember what our set list was or if we even had one. We just knew a lot of songs and were excited to get to go out and start playing them for people. In those days, we would do a forty-five-minute set, take a fifteen-minute break, and then do another set. We would do four sets.

Kent gave guys like me a place to hone our skills. The live music scene back then was great, and we had some of the best places to play. It doesn’t get any better than Cheatham Street, Gruene Hall, and the Broken Spoke, and those old dance halls and honky-tonks were where we learned to play in front of people. I’m not sure I would’ve been ready to do that if I had been signed to a record label right away. I needed those years to learn how to play and sing on stage.

Kent was friends with a songwriter named Darrell Staedtler, and he introduced us. Darrell was writing for Chappell Music back then and needed to go to Nashville to demo some of his songs and asked me if I would sing on the demos. I had been wanting to go to Nashville forever, so I was excited and ready to go, just to maybe open some doors for us. So Kent and Darrell and me loaded up Kent’s delivery van with a few cases of Coors beer since they couldn’t get Coors in Nashville at the time. We put a cot in the back, and I think there also was a lawn chair, and off we went. It was a great trip for me and gave me some studio experience, which I needed. I thought the demos turned out great and just knew I would be signed if the right person heard them. I was so wrong. I remember Kent and Darrell were very encouraging, though, and didn’t let it get me down. We came back to the great state of Texas and continued to play music and have fun.

Kent was writing, and of course Darrell encouraged me to write as well. I wrote “I Don’t Want to Talk It Over” and “[That] Don’t Change the Way I Feel about You” back around 1976. I remember how hard it was to introduce them to the band to learn. I mean, you never know how someone else is going to react to your songs, but I still have plans to record those songs again someday. I redid “I Just Can’t Go on Dying Like This” on my last record [2013’s Love Is Everything] and thought it turned out pretty good. I wrote that one about the same time. I’m not sure of the inspiration behind those songs. I guess it was just life in general.

I think about those days all the time. Those memories will be with me forever. It’s part of my history as an artist. I think about the great old music we were playing back then and how we would order some beers to the stage during the set if we were thirsty. Beer was free for the band, and we were always thirsty, it seemed. I think about all of the great crowds we had and people filling up the dance floor. That’s how you knew you were doing well. If they weren’t dancing, you were doing something wrong. We didn’t make a lot of money, but we were doing something we loved and getting paid for it.

The reason I thanked Kent from the stage on the [2014 farewell] tour was because I wanted people to know some of those stories and know who played a part in my career. Kent was a very important part of that. He is a friend and was an inspiration to me and a whole slew of others he let on that stage at Cheatham Street Warehouse. He knows good songs and knows good music. I went there a lot as a spectator, and I never once saw a band there that sucked. He wasn’t going to let you play there if you sucked. I mean, just look at the amazing list of people who have played there. I saw Ernest Tubb at Cheatham Street. How cool is that? I think that was a dream of Kent’s all along: to give a platform to artists to develop their skills and just have a damn fun way to make a living. Kent and his band would play there as well, and it gave him a chance to introduce some of the songs that he was writing at the time. That’s how I think Kent will be remembered, a guy who was a friend to the songwriters and artists in our great state of Texas, who believed in our music and was willing to do his part to help you get to wherever it was you wanted to be.

From Kent Finlay, Dreamer, by Jenni Finlay and Brian T. Atkinson. Copyright © 2016 by Brian T. Atkinson and Jenni Finlay. To be published in 2016 by Texas A&M University Press.