The Young Caregivers

Very little is known about the million-plus American children providing significant medical care for adults. Melinda Kavanaugh wants to change that.

After Brennon Colburn’s father was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – commonly known as ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease – his dad’s health rapidly declined. So Brennon, then 13, biked several times a week through the streets of Oshkosh from the home he shared with his mother to his father’s house. There, he did laundry, carried his father upstairs, and even helped him bathe and use the toilet.

“He used to do that for me,” Brennon says. “I felt sad, but I felt like I owed it to him.” He’d repay the debt for nearly two years until his father’s death in October 2016.

Brennon was part of an invisible army of children providing short- and long-term medical care to adults. It’s a phenomenon at the core of Melinda Kavanaugh’s research at the Helen Bader School of Social Welfare.

Only a handful of people nationwide study the topic, however, and she bemoans the small knowledge base for something more common than you’d think.

An estimated 1.4 million children in the United States could be classified as young caregivers, the total reported by a 2005 study. That study, a collaboration between the National Alliance for Caregiving and the United Hospital Fund, was the first attempt to discern the prevalence of young caregivers, and it remains the only one.

Kavanaugh, an assistant professor of social work, thinks that estimate is low, considering all the factors involved. “You think of how many people have a disease,” Kavanaugh says, “and it’s hard to get care anyway, and we know that most care is provided by family members.

“So, of course, kids are going to get involved,” she continues. “But how they are involved, and the impact of their involvement, is what we study.”

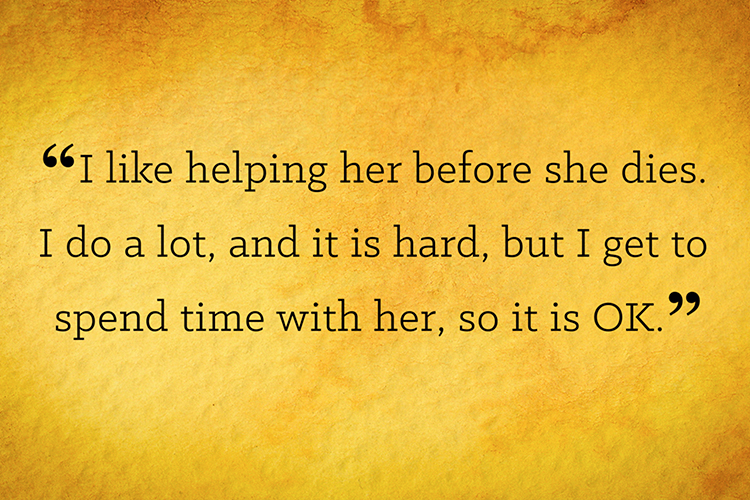

Most of Kavanaugh’s research involves interviewing children ages 8 to 19, but some as young as 6 have expressed an interest in talking about their experiences. The tasks they handle vary depending on age, but Kavanaugh shares how even some 8-year-olds have helped parents get dressed, bathe, use a feeding tube or administer medication.

“We do know that these kids grow up fast,” she says. “One thing I hear a lot is, ‘I lost my childhood.’”

It manifests in something as simple as being unable to play after school because an ill parent is waiting.

Kavanaugh has learned that children hardly ever get training in how to give care, even (or especially) for medical procedures. For many, the best-case scenario is that they watch an adult do it once. They are often afraid of a mistake that will make things worse.

So Kavanaugh goes beyond using her research to inform practice and toward making a difference in the lives of her subjects. “I really connected with her,” Brennon says. “She told me that this is what’s going to happen, and I’ve got to face the facts. She told me that he was still the same person, even if he couldn’t talk or eat. She wasn’t acting like a social worker to me. It was more like she was a mentor.”

And Kavanaugh never wants to overlook that part of her job. She spent the first part of her career as a social worker in health care settings and pursued her doctorate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison so she could research young caregivers. “Sometimes, being in research is therapeutic in and of itself,” she says. “You’re letting them tell the story, and you are bearing witness.”

She’s found parents are proud of their children for their care contributions, but also feel guilty about needing those contributions. A key question, without a definitive answer yet, is how many parents rely on a child because they can’t afford anyone else.

The few federal and state programs that aid family caregivers are often underfunded and don’t acknowledge caregivers under 18. In the United Kingdom and Australia, family members, including children, are eligible for financial support and respite care. “Light-years ahead of anything we have here,” Kavanaugh says.

Because the issue of young caregivers is so far beneath the radar, Kavanaugh’s duties often include a public education component. When speaking about it with policymakers, she concentrates on economics and how children’s home responsibilities keep them from being engaged at school, so they’re less prepared for the workforce.

Federal research tracks children’s health, but the physical, mental and emotional impact on a child caring for a family member falls through the cracks.

“Emotionally, it was my normal,” says 16-year-old Ian Turley of Menomonee Falls, who spent some four years in a caregiving role before his father died of ALS in 2014. “I didn’t know what having an able dad was. You think that any person could be responsible for someone in that situation.”

The situation can be made better, however, particularly if children are acknowledged and valued. “They need support,” Kavanaugh says, “and friends who understand it, and people to help them provide care.”

Among the support outlets for young caregivers are summer camps, which are often sponsored by disease-centric organizations. In 2016, Kavanaugh asked Ian to speak to an audience of younger children living with an ALS patient, which helped speaker and listeners alike.

Stan Stojkovic, dean of the Helen Bader School, says that as the U.S. population ages, caregiving in general will become a more important area of social work. He says Kavanaugh is ahead of the curve on the other end of the age spectrum, and that helps UWM in more ways than just funding and exposure. “The real benefit,” Stojkovic says, “is her connection to the community. It’s good for the campus and the students and faculty.”

As an example, in one of Kavanaugh’s current projects, she’s working with Milwaukee’s United Community Center on school-based interventions for Latino youth caregivers. “I value research with a translatable component,” she says. “How can it really, truly go back to the community?”

And while continuing to move her research forward with every child she interviews, she remains connected to her past.

“I can still close my eyes,” Kavanaugh says, “and be that social worker doing a home visit, seeing the youth as a caregiver.”