50 Years Ago, Americans Fired Their Dysfunctional Congress

Like Obama, JFK and LBJ found their agendas stymied by a hostile Congress, until American voters stepped in to demand change.

It’s almost impossible to find anyone who is optimistic about Congress. The good news is that this is not the first time we’ve despaired over congressional dysfunction. In fact, in the years leading up to one of the biggest outbursts of legislative productivity—the passage of the Great Society in 1965 and 1966—there was a huge chorus of critics who decried the inaction of Congress. Revisiting that history can teach us about how to navigate the present political morass.

We just finished one of the least productive sessions in American history. Partisan gridlock, incivility, and extremism have paralyzed Capitol Hill. There are not many observers who believe that President Barack Obama’s current policy agenda stands much of a chance of passing through a broken Congress.

Whereas Obama has been stymied by congressional Republicans who controlled the House and capitalized on minority power in the Senate, John F. Kennedy squared off against a coalition of southern Democratic committee chairmen and Republicans. Since the 1937 backlash against Franklin D. Roosevelt, this conservative coalition had been the principle roadblock to liberal reform. Southerners, elected to safe districts, thrived in a committee system based on seniority.

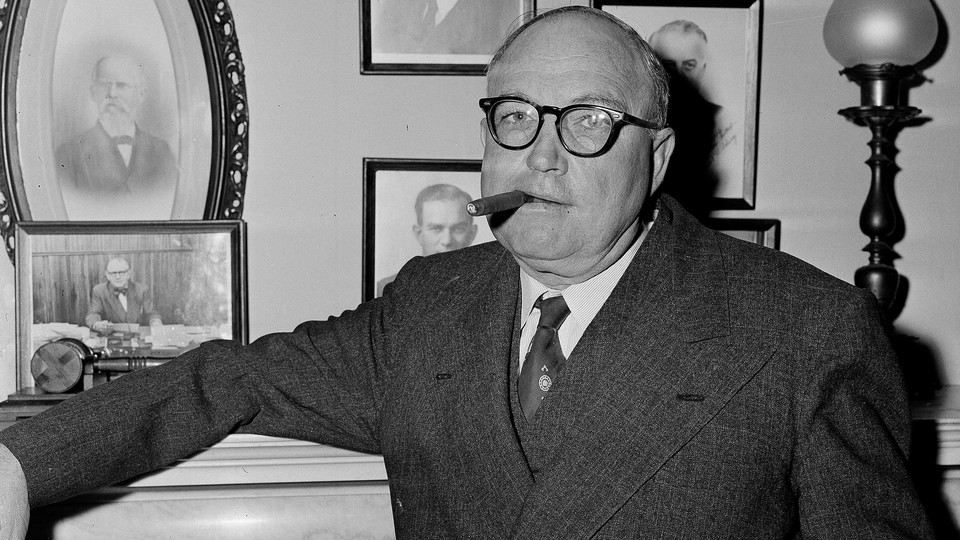

The longer a person stayed in office, the more power they obtained. Senator James Eastland of Mississippi, an ardent racist, chaired a subcommittee responsible for civil rights. He liked to joke that he had special pockets made in his pants just to carry around all the bills he wouldn’t let come up for a vote. In the Senate, southerners killed bills through the filibuster, which, according to journalist William White, made the upper chamber “the South’s unending revenge upon the North for Gettysburg.”

By the time that Kennedy was elected president in 1960, liberals had lost faith in the existing Congress. Democrat Senator Joseph Clark called his colleagues the “sapless branch” of government and wrote that the conservative coalition was the “antithesis of democracy.” Soon after Kennedy’s election, the House Rules Committee Chairman Howard Smith, who had once pretended there was a fire on his barn in Virginia just to prevent a vote on a civil-rights bill, told reporters that he would “exercise whatever weapons I can lay my hands on” to stop the new president.

Though Kennedy’s critics complained that he was too disengaged on domestic policy, even when he did move forward with legislation, the coalition remained powerful enough to block much of his progress.

On every major domestic issue, Kennedy failed to gain any traction. “I think the Congress looks more powerful sitting here than it did when I was there in Congress,” the president admitted.

Despite Kennedy’s reputation for coolness, he undertook an aggressive campaign to push his proposal for Medicare, a bill that would provide hospital insurance to the elderly, paid for by Social Security taxes. The administration worked with organized labor to build pressure on members of Congress. In December 1962, the president spoke at a massive televised rally in Madison Square Garden to urge citizens to demand that their representatives support him. At the same time, top officials in the Social Security Administration worked behind the scenes to conduct negotiations with the main committee chairs over the details of the legislation. The campaign did significantly broaden public support for Medicare.

But the opposition to Medicare within Congress was stronger. Members of the conservative coalition were firmly opposed to Medicare, which the American Medical Association branded as “socialized medicine.” The chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Arkansan Wilbur Mills, refused to let the bill come up for a vote. The AMA conducted the most expensive lobbying campaign in history to oppose Medicare. It sent pamphlets to the offices of physicians so that patients leaving their appointments would read warnings about how government bureaucrats would make the decisions at their next visit.

Then there was the civil-rights legislation, aimed at ending racial segregation in public accommodations. The civil-rights movement, led by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., had been steadily mounting grassroots pressure for President Kennedy to send a bill to Congress. At first, Kennedy hesitated. Top advisers, including the ardent civil-rights supporter Harris Wofford, convinced the president that a bill would tie up the rest of his agenda, but couldn’t even make it out of committee. James Foreman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee complained that Kennedy was a “quick-talking [and] double dealing politician.”

The movement didn’t take no for an answer. As the protests in Birmingham, Alabama, in April 1963 brought international attention to the white violence that African Americans faced in Dixie, Kennedy was finally persuaded to move forward with a proposal. The protests had created enough support among Republicans to get the legislation through the House Judiciary Committee. But the administration was still uncertain whether the legislation could make it through the House floor or survive a filibuster.

When Lee Harvey Oswald killed Kennedy in November 1963, most of the president’s domestic agenda was stalled. In Life magazine’s memorial issue for JFK in December, the lead article by the editors warned: “The 88th Congress, before the assassination, had sat longer than any peacetime Congress in memory while accomplishing practically nothing. It was feebly led, wedded to its own lethargy and impervious to criticism. It could not even pass routine appropriations bills. It was a scandal of drift and inefficiency.”

The first year of Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidency saw more progress. Most importantly, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The success of this bill, however, stemmed from the overwhelming pressure placed upon Congress by the civil-rights movement. It also relied on the impressive organization and tactical fights that liberals mounted against the southern civil-rights filibuster in the spring of 1964.

Outside of civil rights, Johnson’s gains remained limited. The situation was better than one year earlier, but Congress was not yet ready to endorse a Great Society. Congress did pass the War on Poverty, but the program obtained a very meager budget that paled in comparison to most other major domestic programs. To secure support for an across-the-board tax cut, LBJ agreed to hold the federal budget under $100 billion, so that he could obtain the support of Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia, the conservative chairman of the Finance Committee. Most of his advisors agreed this was insufficient to fund any new programs of major significance,

Grassroots pressure was not always enough to move a bill as it was on civil rights. While Johnson kept pushing for Medicare, conservatives in Congress didn’t seem moved by the sentiment surrounding Kennedy’s death to pass a bill. When liberals in the Senate tried to circumvent Wilbur Mills by adding Medicare as an amendment to Social Security legislation, Mills killed the proposal in conference committee.

Then everything changed. In the 1964 elections, Johnson defeated right-wing Republican Barry Goldwater in the biggest landslide since 1936. Voters elected huge liberal majorities in Congress, rejecting Goldwater’s brand of right-wing conservatism. Democrats reminded voters that Goldwater had voted against civil rights, and stood opposed to programs such as Medicare. While Johnson touted his liberal agenda, his main goal was to depict Goldwater, and the kind of extremism that was common on the Hill, as far from the political mainstream.

Democrats came out of the election with 295 seats in the House and 68 in the Senate. The balance within the Democratic Party shifted decisively to the liberals. Most Republicans were terrified of being associated with the conservatism of Goldwater, lest they suffer the same fate.

As a result of the election, Johnson had all the votes that he needed to move forward with his bills. “There were so many Democrats,” Illinois Republican Donald Rumsfeld said, “that they had to sit on the Republican side of the aisle.”

Congress passed Medicare and Medicaid, federal aid to elementary and higher education, the Voting Rights Act, environmental regulation, and much more. Opponents of liberal reform realized that they would be beat. “Suddenly, after years of deadlock,” Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota recalled, “the floodgates burst open.” After Congress passed immigration reform, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts noted: “It’s really amazing. A year ago, I doubt the bill would have had a chance. This time it was easy.”

The window for legislating was short. In the 1966 midterms, a backlash against civil rights and political unrest over Vietnam allowed the conservative coalition to regain its strength in Congress. Republicans gained 47 seats in the House. The Democratic majority shrunk to 248 in the House and 64 in the Senate. “We’ve beaten the hell out of them,” Richard Nixon boasted to his advisors upon hearing the results.

Today, President Obama faces a Congress that will be just as obstructionist as the one that Kennedy faced, but he lacks the same kind of vibrant grassroots liberal movement that existed at the time. Regardless of how much Obama twists arms or how aggressive he is toward the GOP, he will not be able to make much progress with his legislation.

That doesn’t mean the future will always be bleak. The 89th Congress is proof that average Americans have the capacity to dramatically alter the status quo. In 1964, the civil-rights movement was able to put the pressure on Congress necessary to end segregation. That fall, voters elected huge liberal majorities that were ready and eager to pass many bills. An overwhelming majority of voters also rejected the kind of conservatism that Goldwater was peddling.

If Democrats are going to fundamentally change the dynamics in Washington, they will need to focus on the next series of elections in 2016 and 2018. They must also pay more attention to government reforms on matters such as partisan gerrymandering that make it hard to swing the composition of the House, so that future presidents have a better playing field.

If voters don’t change Washington, nobody else is going to do it for them.