I spot Lin-Manuel Miranda half an hour before our interview, strolling through the New York hotel where we have arranged to meet, bouncy as a puppy, cocky as a rooster. I had been a little worried about his mood, because earlier he had tweeted to his 2.5 million followers that “my kids slept VERY little last night” and that he was “grumpy/hangry”. But no man has looked less grumpy/hangry in the history of mankind. He bounds down the hallway, tossing his phone from hand to hand, not just smiling at passersby who recognise him, but catching their eye, encouraging recognition. Miranda grew up only a couple of miles away, a second-generation Puerto Rican immigrant who was so obsessed with musicals and hip-hop that he listened to his cassettes until they broke. Here he is today, the crown prince of Broadway, decked with Oliviers, Emmys, Tonys, a Grammy and a cherry-like Pulitzer on top, thanks to his blockbuster hip-hop musical, Hamilton. It is hard not to be a little bit charmed by the sight of a man who, still under 40, is clearly living his wildest dreams.

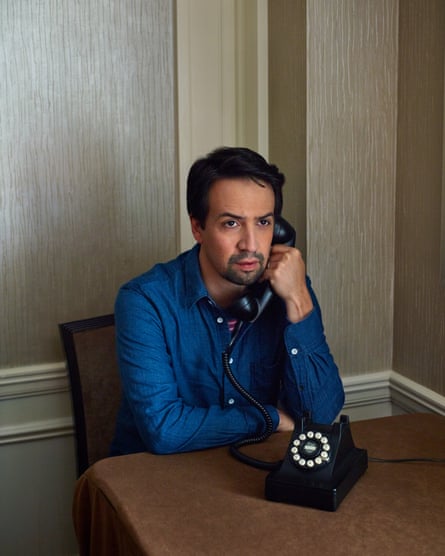

Eventually, I am taken into the room where Miranda is waiting – with a retinue, it turns out. Among the various publicists, there is a man with a camera who continually snaps pictures of Miranda and, as I sit down next to him on the sofa, me. “He’s following me around for a thing. Smile, you’re famous now!” Miranda grins, his leg jiggling with energy. He is wearing a denim shirt and soft cotton trousers, as well as his signature goatee. He is small but stocky and full of eagerness to please, a circus cub ready to perform.

Click click goes the photographer, chronicling his every gesture. Alongside the photographer is a man who Miranda says is there “to keep away the intrusions”, meaning, presumably, a quasi bodyguard. Miranda, 38, has had a lot of intrusions in the past three years. His first musical, In The Heights, which opened in 2008, won him several awards and respect within the industry. But Hamilton, his ingenious musical about Alexander Hamilton – “The 10-dollar founding father without a father,” as Miranda’s lyrics put it – made him a bona fide mega-celebrity. The show has since gone global – it opened in London in 2017 – and Miranda has been feted by everyone from the Obamas to Oprah Winfrey. He managed to create something no one in the history of musicals had created before: a genuinely cool Broadway show. The hip-hop stars Miranda grew up worshipping – Busta Rhymes, Jay-Z, Queen Latifah – have all been spotted in the audience, applauding his virtuosic skill at turning even the driest details of US history into epic rap battles.

Today, we are here to talk about Mary Poppins Returns, a sort-of sequel to the 1964 Disney film, this time starring Emily Blunt as the airborne nanny. If you loved Paddington, with its vision of pretty, twee London, but would have preferred a flying woman instead of a talking bear, you are in luck. I can’t really see the point in remaking a classic musical, but railing against Hollywood reruns is like shaking your fist at the clouds, so we may as well lean back and enjoy. Miranda plays Jack, a lamplighter who, as a child, worked as an apprentice to Dick Van Dyke’s Bert. I am sorry to inform you that, as well as teaching Jack how to light lamps, Bert bequeathed him his deeply unfortunate accent. “Oooh, the lahvely Lahndahn skoyyyy!” sings Miranda in the film’s opening number, cycling through cobbled streets in a baker boy cap.

You know Britain is never going to forgive you for this, I tell Miranda. “Whatever do you mean? Bert’s accent was spot on! I think the problem was his accent was too good. It humiliated British people that he went to their home court and played it so well!” he replies with mock indignation. “No, I know, it’s funny. Dick told me that, too. He’s like: ‘They still haven’t forgiven me!’ Haha! You guys traumatised him so bad that, in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, he didn’t even try to put on an accent.”

Miranda insists that his English accent is completely different from Van Dyke’s. Um, is it? “Oh yes, I didn’t go so far as to put on a cockney accent – that’s the triple Lutz of accents! I went more East End – more Anthony Newley and Billy Bragg, that’s where I aimed.”

Miranda’s schedule being what it is, we don’t have time to debate the location of Bow bells, so I ask if it was weird singing songs he didn’t write. The songs in Mary Poppins Returns were written by Marc Shaiman, a brilliant and experienced songwriter, but his work here is not a patch on A Spoonful Of Sugar or Feed The Birds.

“It was a relief,” Miranda says, with a stagey sigh. “I’ve been working my butt off so I could earn the right to sing songs I haven’t written. You know, the only reason I started writing musicals was because I loved musicals but couldn’t see my way in.”

US musicals have long been a white, stuffy closed shop. Even Porgy And Bess was written by three white men (George and Ira Gershwin and DuBose Heyward). But through sheer talent Miranda broke his way in and, instead of treating his ethnicity as something to be ignored, presented it as an advantage. He started writing In The Heights while he was in college, setting it in his neighbourhood of Washington Heights and focusing it on the dreams and struggles of his Hispanic community. After its early Off-Broadway success, it went to Broadway, where it won four Tony awards. This paved the way for Hamilton, which tells the story of the founding of the US with a Hispanic and African-American cast (on Broadway, Miranda cast himself as Hamilton, the irresistibly handsome genius).

That he, a Puerto Rican American, has been cast as a cockney lamplighter in a mainstream Disney film is testament to his success at promoting colour-blind casting. Aside from Mary Poppins Returns, he has contributed music to the 2016 Disney film Moana and is writing songs for Disney’s forthcoming live-action version of The Little Mermaid. Is it a coincidence that Miranda and his wife, Vanessa Nadal, have two sons, Sebastian, four, and Francisco, one? Is he picking his post-Hamilton work according to what his children can watch?

“The honest answer is there are things inside me I want to make – Hamilton is one of those things, Heights was another. And since the success of Hamilton, my life has been about finding the balance between the things I always wanted to make and the opportunities that are so incredible I’d be angry if they opened and I wasn’t in them. So Mary Poppins and Little Mermaid definitely fall into that category. I think there is always a part of me that is checking in with childhood Lin and asking: ‘Would little Lin be freaking out about this?’ If the answer is yes, then I say yes,” he says.

It takes a moment before I realise his answer to my question is no, he isn’t making these movies for the kids he has – he is making them for the kid he was.

Miranda lived in London while he made Mary Poppins – in Notting Hill, the one place in England that looks vaguely like the England of Mary Poppins Returns. “The timing was perfect, because it was right in the middle of all the Hamilton stuff. So what do you do when life gets a little crazy? You run away and join the circus!” he laughs.

“The Hamilton stuff” refers to the furore that erupted when Mike Pence, then the US vice-president-elect, went to the Broadway show shortly after the 2016 election and was booed by the audience. With its focus on the value of immigration and political idealism, Hamilton has widely been seen as a riposte to Donald Trump, not least by Trump himself. That night, Brandon Dixon, an African American actor in the New York production, addressed Pence from the stage after the show: “We are the diverse Americans who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents… We hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and work on behalf of all of us.” The newly elected president was outraged and tweeted: “The cast of Hamilton was very rude last night to a very good man, Mike Pence. Apologize!” (They did not apologise, making Hamilton the site of Trump’s first failure as president.)

But Miranda shies away from making political statements. “I feel very ill-equipped when people ask me about politics. Honestly, I do. I’ll never forget, my first interview was three months into Hamilton and the reporter kept asking these political questions and I was like: ‘Does anyone give a shit what I think about this?’”

I assure him they do. “I find that surprising, because the politics inherent in Hamilton are: everything that was at the origins is still here now, such as the original sins of slavery and gun violence – we’re all still dealing with the ramifications of those. So the notion is everything past is present and that’s about as political as the show gets. I do not think that qualifies me for politics.”

What would a musical of Trump sound like? Miranda makes a long exhale. “Here’s where you write: he exhales for 20 seconds,” he says. “I don’t know. It’s so much noise right now. I feel like we careen from headline to headline and the real story won’t emerge for years. I don’t know how to score that yet.”

Miranda’s stay in London – the first time he had lived outside the US – coincided with the Brexit referendum and the US election. “We were there for a very strange time,” he says solemnly, before quickly perking up: “But the silver lining to all that is we were making this movie that is just unalloyed joy. So you’d read a headline and see hardship, then you’d go to work and say: ‘Well, we’re making [Mary Poppins]. That is literally just designed to make people feel deliriously happy.’”

It didn’t feel a bit irrelevant, given how politically relevant his last show was? “No! It felt good putting our psychic energy to something like that during a very unrestful time in both countries.”

His time in London also coincided with the casting of the London production of Hamilton, so I suggest he had the perfect balance: on the one hand, the simple joys of Mary Poppins; on the other, the anti-Brexitness of Hamilton. He makes an “I don’t think so” face at the idea of Hamilton being anti-Brexit, so I say that the show emphasises multiculturalism as part of a nation’s story, which is the kind of thing Brexit denies.

“Mmm, yes,” he says uncertainly. “But the real silver lining to being in London was I got to see Giles Terera and Jamael Westman’s auditions, so I got to be in the room where it happened!” he says, quoting one of his own songs from Hamilton. (Terera and Westman play Aaron Burr and Hamilton, respectively.)

Before meeting Miranda, I spoke to a couple of people who had worked with or met him socially. Everyone told me the same thing: he is just like Hamilton. With his inexhaustible energy and obvious intelligence, it is easy to see why the comparison gets made, but the more I talk to him, the more he reminds me of Hamilton’s nemesis Aaron Burr, the man who never says what he thinks. Despite what he says, Miranda is far too smart, and has written too political a show, to claim with any credibility that his opinions are uninteresting. But, as Burr says, when you say what you believe, “every proclamation is free ammunition for your enemies”.

“I live in fear of saying the wrong thing, no matter how voluminous my Twitter output, and I get paralysed by choices [like Burr does],” Miranda agrees. “With Hamilton, before I recognised myself in him, I recognised my father.”

Miranda was born in New York City, the son of Luz Towns, a clinical psychologist, and Luis Miranda Jr, a political consultant, although that doesn’t begin to describe his father’s achievements. Since arriving in the US as a teenager with little English, he has worked for three New York mayors and Hillary Clinton’s successful campaign for the US Senate, as well as serving as the founding president of the Hispanic Federation, a non-profit organisation – and that is not mentioning the multiple boards he sits on. It is not hard to see where Miranda got the inspiration for Non-Stop, the song in which Burr stares at Hamilton in wonder: “Ev’ry day you fight like you’re running out of time / Keep on fighting in the meantime / Non-stop.”

His son was a smart kid – “and spoiled”, Miranda admits – whose parents were always supportive of his theatrical leanings. When he was eight and had to write a book review for school, he made an impressively elaborate movie of the story, with his father on camera duty and his mother, sister and great-grandmother roped in as actors. (He has since put the footage on YouTube.) Miranda Jr later recalled watching his 10-year-old son on TV, performing with his school choir for a charity event. “There are 20 kids singing, all very shy, and there is Lin-Manuel,” he said fondly, flinging his arms around in imitation of his attention-grabbing son.

After college, Miranda was offered a teaching job at his old high school and wrote to his father asking for advice: should he do the safe thing or pursue his dreams? “I really want to tell you to keep the job – that’s the smart ‘parent thing’ to do,” his father wrote back. “But when I was 17, I was a manager at the Sears [department store] in Puerto Rico and I basically threw it all away to go to New York. I didn’t speak a lot of English. It made no sense, but it was what I needed to do.”

Today, Miranda and his young family live just a few blocks away from his parents and the place where he grew up. “I walk around there and people are like: ‘Oh, that’s Lin.’ There’s none of the urgency, like if I’m walking on Broadway and it’s like: ‘Oh my God, he’s here!’ There’s none of that.” This time, his relief is unexaggerated. His wife also helps keep things normal, he says: “After all, I married a woman from my neighbourhood.”

Miranda and Nadal were childhood sweethearts and their wedding video, which is also on YouTube, gives an interesting insight into their relationship. He surprised his new bride by getting their families and friends to join him in an impromptu performance of L’Chaim, from Fiddler On The Roof. It is an undeniably charming testament to Miranda’s love of classic musicals, but it also puts the bride in the position of being in the audience on her wedding day – which, it has to be said, Nadal seems to enjoy immensely. In their family, it seems Miranda is the performer and Nadal the supporter.

As a husband, he must be – I begin, but he interrupts. “I’m as much of a pain in the ass as any other husband,” he tells me with a reassuring pat on the leg, apparently in the belief I was about to say “wonderful”, when I was going to say “exhausting”.

“I have to be told 50 times to get off Twitter. And I’m a writer, so I’ll tell my wife: ‘Honey, I’ll make you bagels,’ then I’ll have an idea for something, so I’ll go to my room to write and she’ll come in with these burnt, on-fire bagels that I forgot to finish. So it’s not easy to be married to me. But I think we complement each other very well. My wife is incredibly smart and resourceful, but also incredibly silly and fun. So we have a good yin-yang.”

There is no doubt Miranda is enjoying his celebrity – and quite right, too: he earned it through his extraordinary drive. But the longer I spend with him, the more his hamminess feels like jazz hands to distract people from the quietly private man he is, albeit one who really, really loves to sing and dance and fling his arms about, and put his wedding video on YouTube.

These days, Miranda dreams of taking “a month off in a hammock”, but he is deep in preparation to take Hamilton to Puerto Rico and has “at least three” other ideas cooking: “I check on them like a chef, like: ‘How are you? Still raw? OK, let’s let you wait.’”

Why keep working so hard when there is no longer a financial imperative? Why not just lie in the hammock? For the only time during our interview, Miranda is momentarily lost for words: “Well… well… there’s this sense that there are all these ideas waving their hands at me and I don’t know if I’ll have time to get them out. What if I don’t get them out? That’s the main driver,” he says.

To quote a certain musical, the man is non-stop.

Mary Poppins Returns is out on 21 December.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).