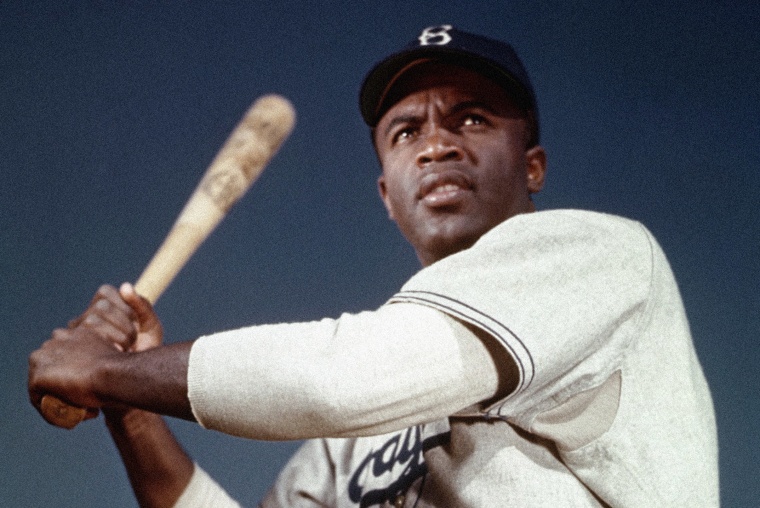

Major League Baseball’s decision to move the All-Star Game from Georgia to Colorado created shockwaves throughout the sports world. I've argued that one of the biggest factors in the league’s choice can be boiled down to two words: Jackie Robinson.

Every year on April 15, the sport commemorates the Brooklyn Dodgers player’s historic breaking of the color barrier with Jackie Robinson Day — and the last thing MLB wanted was a thousand questions about the hypocrisy of celebrating Robinson while holding its All-Star Game outside Atlanta. (And if you still don’t understand why the state’s newly enacted election law is racist, this thread will be helpful.)

But what would Robinson himself have thought about moving the game? Are we correct to claim the moral authority of Robinson, who was famously a Republican himself until he quit the party, by saying definitively that he would celebrate the decision? After speaking to six sports historians, I feel very comfortable answering “hell yes.”

Howard Bryant, a journalist, historian and baseball aficionado, told me Robinson all but predicted the current GOP efforts to restrict voting rights.

“At the end of his life, he was becoming more and more pessimistic about the direction in which the nation was headed, and he wasn’t vague about why,” Bryant said.

“He was afraid of and for the Republican Party,” Bryant continued, with Robinson having seen how the party had embraced racism in 1964 when it nominated Barry Goldwater as its presidential candidate. “I think he would have been horrified by the current GOP and it would have increased his resolve.”

Robinson would likely have been “overjoyed,” Bryant argued, “but he also would have been shocked because Major League Baseball at the end of his life was openly hostile to Black people; openly hostile to the idea of Black managers and executives; openly hostile to Curt Flood. So his framework, his starting point would be that anything today looks progressive compared to what baseball was, an entity that conceded nothing to Black ballplayers.”

Amira Rose Davis, an assistant professor of history and African American studies at Penn State, mostly agreed. After his career ended, Robinson “was not just a civil rights advocate, but also someone who believed that business and entrepreneurship were key to Black self-determination and pursuits of equality,” Davis told me.

She pointed to Robinson’s writings on how Black Americans could gain progress through “the ballot and the buck,” which he exemplified during his time as a coffee executive with Chock Full o'Nuts.

“From that platform, he used his position and his athletic celebrity to send letters to President Eisenhower calling for civil rights, very pointedly on Chock Full O’ Nuts stationary,” Davis said. “Or he used checks from Chock Full o' Nuts to fund an NAACP voter drive.”

MLB’s decision to pull the All-Star Game reminded her of those initiatives, but she caveated her assessment with a reminder that Robinson was not pro-union during his time as an executive.

“The movement to get the All-Star Game out of Georgia is not a story about collective action on the part of athletic workers, but corporate pressure,” Davis said. “I think overall, Jack would have supported the MLBs move and seen it and other corporate action in defense of voting rights to be the embodiment of his ‘ballot and bucks’ vision.”

If that weren’t enough to convince me, I also reached out to Richard Zamoff, an associate professorial lecturer in sociology at George Washington University and director of the Jackie Robinson Project, who’s spent years teaching about Robinson and his legacy.

Zamoff was unequivocal in an email: “If J.R. was alive today, I firmly believe he would be an outspoken supporter of MLB’s decision to move the All-Star Game out of Georgia.”

“If J.R. was alive today, I firmly believe he would be an outspoken supporter of MLB’s decision to move the All-Star Game out of Georgia.”

“It’s no coincidence that he was an invited guest on ‘Meet the Press’ to discuss not baseball, but civil rights, race relations, education, housing, substance abuse and other issues facing America,” Zamoff continued. “J.R. never sat on the sidelines. He believed deeply in athlete activism, using his platform to vigorously agitate for social change. By the end of his life, he had realized he had underestimated the intensity of the resistance to social change. He would have understood with clear eyes the efforts of the Georgia and other state legislatures to turn back the clock on equality. And he would have none of it.”

“It’s usually problematic to presume what someone might say about something decades after their death — except in this case,” Chris Lamb, author of numerous books on Robinson, including “Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography” most recently, quickly agreed.

In fact, the only person I spoke with who said Robinson wouldn’t be loudly applauding MLB right now was Nicole Kraft, director of the Ohio State University Sports and Society Initiative. Given how the All-Star Game decision came after the bill became law, Kraft argued, Robinson would instead be trying to have an even greater impact.

“Perhaps that would have meant keeping the game in Atlanta and using it as a platform to highlight voting rights and equity,” Kraft suggested. “It could have turned every at-bat into a statement about the right to vote and against racism.”

But it was Lou Moore, a professor at Grand Valley State University and author of the book “We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality,” who all but closed the case. Here’s what Robinson himself said in an 1956 article he wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier, which Moore emailed me:

To a large extent the Southerners, particularly those in politics are to blame [for Jim Crow]. On the other hand, it’s my belief that baseball itself hasn’t done all it can to help remedy the problems faced by those playing in organized baseball. Baseball, as everyone knows, is big business. Every year millions of dollars are spent in the South directly or indirectly because of baseball. It is my belief therefore that pressures can be brought to bear by organized baseball that would help remedy a lot of the prejudices that surround the game as it’s played below the Mason-Dixon line.

I know there are those who say that the fight for equality isn’t baseball’s to solve. But I remember when there were people who said when Branch Rickey first signed me that I wouldn’t be accepted in the majors. I, and those who have followed me, are living examples of how far-fetched those statements were. That is why I believe that baseball, as an organization, can help combat a lot of injustices.

Here are the facts: During the last decade of his life, Robinson threw off his allegiance to the Republican Party. He saw it as the new party of violence and white supremacy and was very outspoken about that fact. He was also frustrated with the slow pace of the march toward racial justice, not only in Major League Baseball but in the country as a whole. From there, we can only assume he would be like many of us — both outraged by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp’s voter restrictions and subsequently shocked to see baseball take this kind of a stand.

What is absolutely certain is that Jack Roosevelt Robinson would be demanding more: more from baseball, more from the politicians of Georgia and more from all of us. He knew above all else that the fight against racism is not a spectator sport.