Only a few kids in the fourth-period girls’ PE class noticed the new student. She had long black hair and mahogany eyes, and when she walked into the gym, she sat by herself in the bleachers, staring curiously at the other girls in their shorts and T-shirts doing jumping jacks and push-ups. She seemed a little lost, unsure what she was supposed to be doing. It was September 11, 2017, and after two weeks of cancellations caused by Hurricane Harvey, classes had resumed at Santa Fe High School, some 35 miles south of Houston.

Just before fourth period came to an end, one of the students approached the girl in the stands. She had straw-blond hair and turquoise eyes, and she wore a blue T-shirt with a Bible verse, Matthew 4:19, printed on the front in white: “Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

The girl with the blond hair smiled. “I’m Jaelyn,” she said.

The girl with the black hair smiled back. “I’m Sabika.” She said that she was a foreign exchange student from Pakistan.

“That’s so cool,” said Jaelyn. “Pakistan.”

The girls kept talking. Jaelyn told Sabika her full name was Jaelyn Cogburn. She was fifteen years old, a freshman, and new to the school herself, so she didn’t know many people. Sabika said her full name was Sabika Sheikh. She was sixteen, a junior. She didn’t know anyone at all.

The bell rang, and Jaelyn and Sabika moved on to their other classes. At the end of the day, Jaelyn hurried out to the parking lot, where her mother, Joleen, was waiting. When Jaelyn climbed into the passenger seat, she mentioned the girl she had met in her PE class. “Mom,” she asked, “where’s Pakistan?”

“It’s on the other side of the world,” Joleen said. She gave her daughter a quizzical look. “Are you sure she said Pakistan?”

Despite its proximity to Houston, Santa Fe, with a population of 13,000, still feels very much like a small town. Joleen, who is 35, and her husband, Jason, 46, live with their six children (three of whom are adopted) on three and a half acres in a comfortable two-story home next to a small pond. Their neighbors grow vegetables and own livestock. “To be honest with you, not much happens down here,” Joleen said one afternoon, sitting at her kitchen table. She let out a light laugh. “Well, one day our pastor did run into a cow on his way to church.”

Santa Fe is a deeply conservative community. In 2000 the town attracted national attention when officials from the school district appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court to defend their practice of conducting public prayers before football games. (They lost the case.) And the Cogburns are the town’s Brady Bunch. Every Sunday, Joleen and Jason take their children to Santa Fe Christian Church, which holds as a central tenet that the Bible is literally true. The affable Joleen, who grew up in Santa Fe, sometimes teaches a women’s Bible study class. On Friday nights, the equally good-natured Jason, a former high school quarterback from nearby Texas City who owns a wholesale seafood and crawfish company, would lead a recovery group for addicts and alcoholics. “We are Kingdom-minded,” Jason explained, brushing his shoulder-length blond hair out of his eyes as he took a seat at the table. “We like to tell our children that we live in this world but that we are not of this world.”

Like all of the Cogburn children, Jaelyn, the oldest birth child, had been homeschooled by Joleen, who followed a Bible-based curriculum. Jaelyn was shy. Outside of her own siblings and a couple of girls from her church youth group, she mostly stayed to herself. But earlier that summer, she had surprised her parents, telling them that she wanted to meet new people. She said that God had “put it on my heart” to go to Santa Fe High.

Joleen and Jason assumed that their daughter would have trouble adjusting to life at a public high school with 1,500 students. Instead, Jaelyn came home on that first day of school, a smile on her face, talking excitedly about meeting a girl from Pakistan. As Joleen began fixing dinner, Jaelyn retreated to her bedroom, where she kept five Bibles on her bookshelf. She googled Pakistan and learned that it is in South Asia, bordered on one side by India and China and on the other by Afghanistan and Iran. She also read that almost all of Pakistan’s 200 million residents are Muslim.

Jaelyn returned downstairs, walked into the kitchen, and told Joleen that Sabika was likely a Muslim. “You know, Mom,” she said, “I’ve never met a Muslim.”

“Well, maybe God has put you together for a reason,” Joleen said. “Who knows? Maybe the two of you will become friends.”

That same night, at the home where Sabika was staying with her host family, a Pakistani-born Muslim couple who had lived quietly in Santa Fe for years, she went to her room and called her parents, 8,500 miles away in Karachi.

It was morning in Karachi, the sprawling port city on Pakistan’s southern border. Sabika’s mother, Farah, and her father, Aziz, had been up with their three other children since dawn—awakened, as they were every morning, by the formal call to prayer that warbled from loudspeakers attached to the minaret above the neighborhood mosque. “Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah” (“I bear witness that there is no god except the one Allah”), the mosque’s muezzin had chanted, his voice echoing through the streets and into the open windows of the Sheikhs’ three-bedroom apartment. “Ashadu anna Muhammadan Rasool Allah.” (“I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.”)

Sabika told her parents about her first day at the American high school. She had been assigned to classes in art, calculus, physics, girls’ PE, and English literature. She mentioned that she had met a few American students, and she was looking forward to getting to know them better.

“And are you being treated well?” Aziz asked her.

“Yes, Baba,” Sabika said. “Very well.”

Aziz is fifty years old, a trim, friendly man who owns a small wholesale business, Al-Basit Traders, that sells women’s cosmetics. Farah, a gracious woman in her early forties, has dark eyes and highly drawn cheekbones, and she wears a traditional head scarf and loose-fitting, floor-length cloak. Every morning they set aside time to read the Quran, and five times a day they heed the muezzin’s calls to prayer. Farah usually prays in her bedroom with the lights off. Aziz prays at home, his office, or the neighborhood mosque where, shoulder to shoulder with other men, he presses his forehead to the ground as he appeals for forgiveness and for intercession against misfortune known and unknown.

They met on January 21, 2000, the day of their wedding, a traditional ceremony arranged by their families. Ten months later, Sabika was born. Aziz and Farah were overjoyed. Holding Sabika for the first time, they whispered a prayer of thanksgiving into her ear: “Allahuu Akbar, Allahuu Akbar.” (“Allah is most great, Allah is most great.”)

From the time Sabika was a young girl, Aziz and Farah had taught her the Islamic commandments for leading a virtuous life—that she should not hold anger, greed, dishonesty, or distrust in her heart and that if she wanted mercy from Allah, she should be merciful to others. They arranged for a Qari to visit their home thirty minutes a day to teach her passages from the Quran in its original Arabic, and they sent her to private schools.

Sabika was a superb student. By the end of elementary school, she was fluent in English. In high school, she won a Golden Pen Award for creative writing, and she scored second in the class’s final exams. She was an avid reader, devouring everything from Roald Dahl’s children’s stories to Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner. After school, she would study for at least two hours at home.

She also made friends easily. “Everyone wanted to be friends with Sabika,” said Duaa Wasim, who had known her since childhood. “She was jolly. She had such a bright face. I called her every day just because she put me in such good spirits.”

On the phone, Sabika would banter with her friends about Pakistani TV dramas and Pakistani pop singers who had appeared on the music show Coke Studio Pakistan. They talked about American television shows they watched on YouTube: American Idol, America’s Got Talent, Friends, and the Ellen DeGeneres Show. And sometimes they wondered what life was really like in America.

With a population somewhere between 15 and 20 million, Karachi is often called one of the world’s least livable cities. The main roads are perpetually choked with motorized rickshaws, motorcycles sputtering clouds of exhaust, dented cars banging over potholes, and wooden wagons hitched to donkeys. At roundabouts, beggars press themselves against car windows while merchants in sandals and soot-streaked tunics hawk pomegranates, baby mangoes, sacks of rice, baskets of live chickens, lemonade, and ice cream.

Parts of Karachi are distinctly modern. There are skyscrapers and universities and fine restaurants. The city’s elite reside in elegant neighborhoods near the sea, their homes tended by servants and encircled by fortresslike concrete walls. Middle-class families like the Sheikhs live on side streets in walk-up apartments, one stacked next to the other.

Many residents, however, are locked in poverty. On the northern and eastern edges of the city, millions dwell in slums—in shabby tents and teetering shanties separated by narrow, sewage-stained alleys or empty lots piled with garbage. There are more than six hundred such slums in Karachi, which are home to roughly 65 percent of the city’s population. According to some reports, up to 40 percent of Karachi’s citizens earn less than $1 a day, and they often lack basic services like water and electricity.

As a result, Karachi is plagued with crime, from petty cellphone thefts to armed robberies and murders (as many as 1,500 a year). Consulates, embassies, and the Jinnah International Airport in Karachi have been targeted by such militant fundamentalist groups as the Taliban and Al Qaeda. To discourage suicide bombers, small armies of soldiers and police officers stand sentry over government institutions, and heavily armed private security guards and bomb-sniffing dogs protect the city’s finer hotels and well-to-do establishments. Many upper-class residents, worried about kidnappers, hire guards to accompany them wherever they go. In 2002 Karachi made international headlines when the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl was abducted on a downtown street and later beheaded.

Still, Sabika loved Karachi. She loved piling into her father’s green four-door Toyota Corolla with the rest of her family for the fifteen-minute drive to the beach, where they strolled along the water that lapped against the gray sand. She eagerly anticipated family visits to the Dolmen Mall, a brightly lit indoor shopping center.

And late in the afternoons, she looked forward to playing badminton on the roof of the family’s apartment with her sisters, Saniya and Soha, and her brother, Ali. The aromas of spice-laden dinners wafted from neighbors’ apartments, and the sounds of the street emanated from below—stray dogs barking, men arguing over politics, an ice-cream vendor pinging the bell on his pushcart. Hitting the shuttlecock gently so it would not fly over the roof’s edge, they would play until the sun set, when the voice of the muezzin resounded through the neighborhood. Then they would descend the stairs back to their apartment, where they knelt in their rooms and offered their prayers to Allah, just like their parents.

Sabika was well aware of her country’s reputation. She had not yet reached her first birthday when Al Qaeda attacked the United States on September 11 and the war on terror began. U.S. officials implicated Pakistan as a breeding ground for extremism, and over the next decade, American military drones flew over the country’s tribal regions, hunting for terrorist hideouts. In 2011, when Sabika was ten, Navy SEALs killed Osama bin Laden in the small northern Pakistan city of Abbottabad, where he had been hiding in a three-story compound. Convinced that the Pakistani government had known bin Laden’s whereabouts for years, many Americans vilified the country as a terrorist haven, filled with angry young men in robes and skullcaps who were determined to bring down Western civilization.

Sabika was disturbed by this characterization of her country, and she told friends and family that she planned to join Pakistan’s foreign service and become a diplomat when she grew up. She said she wanted to show people that the vast majority of Pakistanis were not supporters of terrorism, that they were friendly and accommodating, and that there was nothing to fear about their Islamic faith. She wanted to impact the world like Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani teenage girl who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize after she was shot in the head by the Taliban in 2012 because of her campaign to promote girls’ education.

In the fall of 2016, Sabika’s older cousin Shaheera Jalil Albasit told Sabika about the U.S. State Department’s Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study Program. Established by Congress after 9/11 to strengthen cultural ties with the Muslim world, the program provides funding for high school students from countries with large Muslim populations to study in the United States for a school year. Sabika went straight to her parents and told them she wanted to apply.

Aziz and Farah were uneasy. They had been following the U.S. presidential campaign, during which candidate Donald Trump had proposed that Muslims from particular countries be banned from entering the United States; one poll found that 50 percent of Americans supported his proposal. Aziz and Farah feared that their daughter would be disparaged by anti-Muslim Americans. But Shaheera, who was in the midst of applying to graduate school for public administration at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., reassured them, describing a trip to America as “an unforgettable cultural experience.” They agreed to allow Sabika to apply and sit through the written exams and interviews.

In January 2017, Sabika learned she was one of roughly nine hundred students selected for the prestigious program. She was ecstatic. “I was jumping around like a madman,” she said on a YouTube video she made for friends. In a subsequent email, she received news that she would be sent to the town of Santa Fe, Texas. She and her parents went online and looked at photos of the town and of the high school, a long, boxy redbrick building alongside Highway 6.

To prepare for her trip, Sabika began researching American teenage life. She watched the movies Mean Girls and A Cinderella Story; read Fangirl (a young adult novel about a girl starting college in Nebraska); and studied the motivational bestseller The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens, which the publisher billed as “the ultimate teenage success guide—now updated for the digital age.” She even memorized slang such as YOLO (“You only live once”) and ELE (“Everybody love everybody”).

In August, Sabika packed her things into one suitcase and a small carry-on bag, which contained a notebook she had filled with inspirational sayings. (“If Allah shuts a door on you, stop banging it. Maybe what is behind it is not good for you.”) On the day she left, Aziz and Farah arranged for a Sadaqah, a ritualistic sacrifice of a goat, to protect Sabika from harm during her time away. The goat was brought to their apartment, where Aziz, Farah, and the Sheikh children recited passages from the Quran while petting the animal. The goat was then led away to be butchered so that its meat could be donated to the poor, and the family piled into the green Corolla to take Sabika to the airport.

Despite reassuring her parents that her first days at Santa Fe High had gone well, Sabika confided to her cousin Shaheera that she was struggling to fit in. Her research into American teen life had been futile; she had a hard time following her classmates’ jokes and pop culture references. She also sensed that other students were uncomfortable around her, unable to grasp what she was saying because of her accent.

The one exception, she told Shaheera, was a shy girl in her PE class: Jaelyn Cogburn. Every day during fourth period, Jaelyn happily walked laps around the gym with Sabika, asking her questions based on what she had read online. Was she really not allowed to eat pork because it’s considered unclean? (Correct.) Would she allow her marriage to be arranged by her parents? (Most likely, though she would want to meet him first.) And did she truly believe that the Quran was the final word of God? (Of course, Sabika said.)

During their walks, Sabika, who had never before met a Christian, would ask Jaelyn about her faith. Jaelyn explained that she had devoted her life to Jesus Christ at the age of five. She was a fan of contemporary Christian music, particularly the groups Hillsong and MercyMe, and she wrote religious poetry. (“If I were God I’d end world hunger, I’d stop disease,” one of her poems began, “and give you supper and a life of peace.”) She showed Sabika the Bible app on her phone, and Sabika in turn pulled up her Quran app, along with her phone’s digital compass, which she relied on to face east toward Mecca for her daily prayers. “They were the odd couple, the Christian girl and the Muslim girl,” said their PE teacher, Connie Montemayor. “In a way, it was a perfect pairing of opposites.”

Jaelyn and Sabika began meeting every day for lunch at the school cafeteria. (Sabika stayed away from pork, but she loved cheese pizza and was obsessed with cheese enchiladas and refried beans and rice.) Another student from the PE class, Samantha Lane, an irrepressibly upbeat sophomore who had attended Santa Fe public schools her entire life, gave them a primer on high school life, pointing out the cliques at various tables: the athletes, the cheerleaders, the band nerds, the brainiacs, the loners. Sabika and Jaelyn just stared, utterly absorbed.

In October, Jaelyn invited Sabika to her house to meet her family for the first time. “Welcome to Texas!” Joleen said, giving her a hug. To Sabika, Joleen was like all the American mothers she had seen on television: pretty, outgoing, always ready to drop everything to help one of her children. Over the next few weeks, Joleen drove Sabika and Jaelyn to a movie theater to watch Chris Hemsworth in a Thor movie, to the football stadium to watch the high school’s football team play Texas City, and to the high school auditorium to watch the theater department perform Shakespeare’s The Tempest. On Halloween, Joleen took them to Samantha’s house.

The Cogburns had never celebrated the holiday, so Jaelyn had never been trick-or-treating. Neither had Sabika. Jaelyn dressed up as a pirate, Sabika as a zombie vampire, and Samantha as a ninja. Although Sabika was mystified the entire night by the ritual—one day a year, American kids wore elaborate costumes so they could get free candy?—she cheerfully went along with the other girls, ringing doorbells and trilling in her Pakistani accent, “Trick or treat!”

In early December, Sabika mentioned to Jaelyn that she had asked a representative from her scholarship program about moving in with a new host family. Her host parents were perfectly pleasant, she said, but she really wanted to experience what life was like in a non-Muslim American home. That evening, Jaelyn asked her parents if they would take in Sabika. “Honey, I’ve already got six children to raise,” said Joleen. But she noticed a pleading look in Jaelyn’s eyes that she had never seen before, and it was soon arranged for Sabika to live with the Cogburns.

On December 21, her first night with the Cogburns, Jason brought home pepperoni pizza from Domino’s. When Sabika informed him that she couldn’t eat pepperoni because it was made from pork, Jason was flabbergasted. “What? You’re never going to eat a slice of pepperoni pizza?”

“Never,” said Sabika, scraping the pepperoni off with a fork.

She was given an upstairs bedroom. She hung a Pakistani flag on the wall, and she taped one of her favorite passages from the Quran to her bed’s headboard: La yualid, wala hu mawludun. Walays hunak mithluh. (“He begets not, nor is He begotten, and there is none like Him.”) On the bedroom door, she taped a drawing she had made of an airplane flying over a globe. Beneath the airplane was the phrase, written in English, “Up in the clouds, on my way to unknown things.”

That evening, after the sun set, an alarm on her phone signaled it was time to pray. She shut the door, removed her shoes, unrolled her small prayer rug, placed a scarf over her head, faced east toward Mecca, and began a melodious chant. Without knocking, Jaelyn walked in and paused in the doorway. Sabika continued praying, unfazed. Jaelyn, delighted, crept back downstairs. “Mom,” she whispered, “Sabika is praying to Allah!”

For a couple of days, Jason and Joleen didn’t tell their friends about their new houseguest. They could imagine the response: “What are you doing with a Muslim girl from a country where the terrorists live?” But when Christmas Eve arrived, Sabika said she wanted to go with the family to church. She dressed up in an ankle-length, traditional Pakistani dress and sat next to Jaelyn. She listened in bewilderment as the pastor talked about Jesus being born in a manger to a virgin, and she watched the congregants observe the Last Supper by drinking grape juice and eating wafers. She rose with everyone else to sing contemporary Christian songs, and she closed her eyes during moments of prayer.

The next day, Sabika celebrated Christmas with the Cogburns. Joleen bought her last-minute presents: a camera, a scrapbooking album, a ring decorated with a crescent moon, pajamas, sweaters, and socks. And the week after, she went with the Cogburns to a Christian retreat center in West Texas. There, word spread that Sabika was a practicing Muslim, and a teenage boy confronted her, snidely asking if she was a terrorist. “Stop it!” Jaelyn snapped. “Sabika’s my friend!”

“You’re friends with her?” the boy pressed.

“We’re best friends,” said Jaelyn.

When the new semester began, Jaelyn and Sabika developed a routine. They woke at 6:30, threw on clothes, brushed their hair (neither wore makeup), and ate a quick breakfast. Either Joleen or Jason would drive them to school. The two girls would chatter along the way, and then Jaelyn would walk Sabika to her first-period art class before heading to her biology class on the opposite side of campus.

Just as she had been in Pakistan, Sabika was a straight-A student. In physics, she made nearly perfect grades. In English, she dutifully read American classics such as Of Mice and Men, The Crucible, and The Great Gatsby, and she wrote a research paper on the #MeToo movement. (“One of the best students I’ve ever had,” said Dena Brown, her English teacher.) In history, she gave a presentation about Pakistan in which she described the friendly people and delicious food. And she left an impression in other ways. “I don’t know how to explain this, exactly, but you felt happy around Sabika,” said her PE coach, Montemayor. “She never argued, and she never got upset. She was a peacemaker. I used to tease her and call her my Nelson Mandela.”

Because her scholarship required her to perform community service, Sabika volunteered at the Santa Fe Public Library. She and Jaelyn visited residents at a Texas City nursing home, and they also worked the scoreboard at the girls’ varsity soccer games.

And each evening, after Sabika prayed and called her parents to check on her family and recount the details of her surreal American life, she and Jaelyn would lie in Sabika’s bed—Sabika’s head at one end, Jaelyn’s at the other—and talk late into the night. Using their phone apps, Jaelyn would quote the Bible, and in turn Sabika would quote the Quran. Jaelyn would tell Sabika that Jesus was God’s son and that he was crucified and raised from the dead. Sabika would clarify that Jesus was a fine prophet, but the most sacred of Allah’s prophets was Muhammad, who had received the writings of the Quran from the angel Gabriel. Jaelyn would declare that all a person had to do to get to heaven was accept Jesus as Lord and Savior. Sabika would maintain that the only path to heaven was through good works, as laid out in the Quran.

On and on they’d go, late into the night, until they eventually changed subjects and swapped funny stories about things that had happened at school that day, like the boy who approached them in the hallway and pulled down the collar of his T-shirt to show off a tattoo of angel wings on his chest.

Just as her cousin Shaheera had predicted, Sabika was having an unforgettable experience. She and Jaelyn went to a Super Bowl party, an indoor trampoline park, and a wedding. (Sabika later said she preferred Pakistani weddings, which are elaborate celebrations that last up to four days.) She spent weekends with Jaelyn at the Cogburns’ seafood market—her first job ever—answering the phone and working the cash register. (She eventually ran the entire crawfish department, gushing to customers, “I eat crawfish every day!”) She even began listening to country music: Luke Bryan, Blake Shelton, Lady Antebellum, and George Strait. (Joleen once told her that every Texan was required by law to memorize the lyrics to Strait’s “All My Ex’s Live in Texas.”)

Occasionally, Sabika did encounter tragic aspects of American life. In January, she and Jaelyn learned that a boy who attended Santa Fe High had killed himself. And on Valentine’s Day, they got alerts on their phones that a shooting had occurred at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida. Seventeen students and staff members had been killed and seventeen others were wounded by a nineteen-year-old ex-student armed with a semiautomatic rifle. When they got home, Sabika and Jaelyn turned on CNN and watched footage of students running from the school with their hands in the air, screaming and sobbing. Commentators described it as the deadliest shooting at a high school in U.S. history.

Sabika was familiar with school violence. Over the years, in the tribal regions of Pakistan, the Taliban had forcibly closed schools that educated girls. In 2014, in a particularly gruesome act, gunmen from the militant group Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan ambushed the Army Public School, in the northwestern city of Peshawar, killing 149 people, including 132 students. But Sabika was baffled by what she saw playing out at Parkland. Why, she asked Jaelyn, would an American boy, blessed with privileges that most Pakistanis only saw on TV, go on such a rampage? If he was having a hard time, didn’t he have anyone to talk to? Couldn’t his own family have helped?

During one of her nightly phone calls with her parents, Sabika opened up about the side of American high school life that troubled her. Some of the students seemed so lonely, she said. They weren’t close to their families the way Pakistani children were.

Aziz and Farah asked Sabika if she felt safe, and she assured them there was nothing to worry about. She and Jaelyn were together always; they looked out for each other. “We will never put ourselves in danger,” she said.

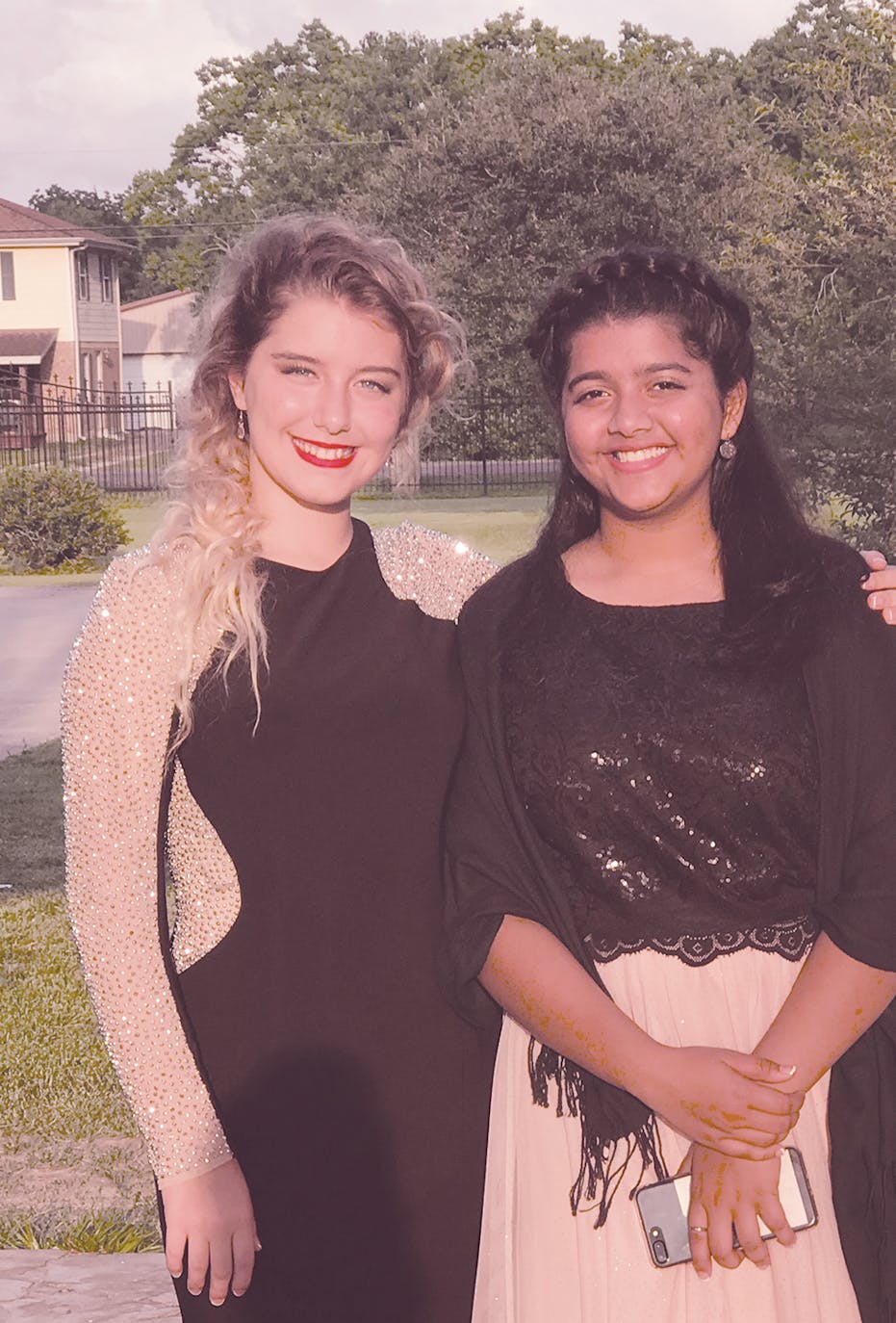

Spring arrived. Her time in the U.S. dwindling, Sabika tried to squeeze in as much as possible before returning home. She wore Jaelyn’s cowboy boots to the Houston Rodeo, where she watched cowboys get slung off of bulls. She attempted to ride a bike (she kept falling off) and drive the Cogburns’ ATV (she bumped into a tree). In early May, she and Jaelyn decided to go to the high school prom together, and they also invited another girl, a shy senior, because they didn’t want her to miss out. Joleen took Sabika and Jaelyn to the mall to buy dresses at Dillard’s. Jaelyn picked out a floor-length black sparkly gown. Sabika settled on a long pink skirt, a black top, and a black scarf that she wrapped around her shoulders. The afternoon of the prom, Joleen did their hair and makeup and snapped their photo in the Cogburns’ front yard.

The prom was held at the Tremont House, a historic hotel in downtown Galveston. Sabika had never been to a dance before, but she stayed on the dance floor most of the night. She giggled and rolled her eyes when a boy attempted to flirt with her. When the prom ended, Joleen and Jason picked the girls up in front of the hotel, and Sabika was elated. “I get to tell my friends in Karachi that I went to a prom,” she said, shaking her head in disbelief.

The Cogburns, though, could tell Sabika was starting to feel homesick. She would sit at her computer and watch replays of cricket matches between the Pakistan national team and its archrival, India. She’d stream the Coke Studio Pakistan television show. During one phone call to her parents, she gave her mother a list of the Pakistani dishes she hoped to eat upon her return: halva, haleem, karahi, and biryani. Aziz and Farah told her they were planning to invite more than one hundred people to their rooftop the day she flew back to Karachi for a welcome-home party.

Sabika emailed her Karachi girlfriends about all that she hoped to do to improve Pakistan. She said her time in America had inspired her to campaign for more public schools, so that all kids could be educated. She wanted to push for more job opportunities for women, and she planned to join a climate change organization. (In the summer of 2015, southern Pakistan had endured a devastating heat wave, leading to the deaths of more than one thousand people from dehydration and heat stroke.)

Still, Sabika was anguished that her time with Jaelyn and the Cogburns was coming to an end. She penned a letter to Jaelyn. “I really don’t know how I’m gonna bear your absence after I go back,” she wrote. “You’re awesome, witty, caring, sensitive, God loving, people loving, naturally happy, positive, and just plain awesome.” (“Awesome” had become one of Sabika’s favorite American words.) She wrote a letter to herself about all that she would miss about Santa Fe. “Dear Me,” it began, “Leaving all of this behind is incomprehensible. Can’t even imagine.”

Sabika was scheduled to return to Karachi on June 9, which meant that she would be spending most of Ramadan, the holiest period on the Islamic calendar, with the Cogburns. Sabika explained to them that every day during the monthlong observance, Muslims are required to fast from dawn until sunset. They are not allowed to engage in thoughts or behaviors considered impure. It is a time of introspection and communal prayer. Sabika told the Cogburns that she couldn’t even drink water.

SABIKA WENT UPSTAIRS FOR HER EVENING PRAYER, AND AS SHE UNFURLED HER PRAYER MAT, THE BEDROOM DOOR OPENED BEHIND HER. THERE STOOD JAELYN, HOLDING HER OWN PRAYER RUG.

Jaelyn, Joleen, and Jason responded in a manner she couldn’t possibly have expected. They said they wanted to fast with her. They didn’t care what their friends might think of them performing an ancient Muslim ritual. “It was our way of honoring Sabika,” said Joleen. “It was our way of letting her know how much she was loved.”

And so, on May 16, the first day of Ramadan, Jason, Joleen, Jaelyn, and Sabika woke earlier than usual and prepared a full breakfast, which they ate before the sun rose. At school, Jaelyn and Sabika still walked laps during PE, but they didn’t take a sip of water. When they got home, they avoided the kitchen. Joleen prepared a dinner of chicken spaghetti, and the family gathered around the table, waiting for sunset. “We can’t eat it yet, but you can smell it!” Sabika said. At precisely 8:08 p.m., they devoured the meal.

Afterward, Sabika went upstairs for her evening prayer, and as she unfurled her prayer mat, the bedroom door opened behind her. There stood Jaelyn, holding her own prayer rug. She placed it beside Sabika’s and said she wanted to pray with her. Sabika nodded, dropped to her knees, and prayed to Allah.

“Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah,” Sabika recited.

“Dear precious Lord and Savior, thank you for this day,” Jaelyn began.

The next day, May 17, Sabika and the Cogburns continued their fast. The morning of May 18, Sabika and Jaelyn quickly ate a predawn breakfast of scrambled eggs, yogurt, and fruit. Jason and Joleen were busy preparing for an upcoming crawfish festival at their store, so they told Jaelyn she could drive the family’s old green pickup to school. (Jaelyn didn’t have a license, but the school was less than a mile away down a back road.) On the way there, they listened to Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud,” and when they reached the parking lot, they sat in the truck and chatted. The bell rang, and Sabika asked if they could hang out a little longer. Jaelyn, though, had a test in her first-period biology class, and she spotted what appeared to be a parking lot monitor coming their way.

After getting out of the truck, they realized the monitor was just another student. “Let’s go back to the truck and keep talking,” Sabika urged.

“We’re already late,” Jaelyn said. “Let’s just go.”

Minutes after Jaelyn took her seat in her biology class, the fire alarm sounded. “It’s probably just a drill,” her teacher said. “Leave all your things at your desks.”

Jaelyn filed out of the classroom and exited the school through a side door with other students. Once outside, several police cars sped past, their sirens screaming. She crossed the street to where other students were gathering in the parking lot of an auto mechanic shop. Jaelyn overheard a teacher saying that there had been a shooting in the art room. Panicked, she sprinted back toward campus, but a teacher grabbed her. In the distance, she glimpsed a girl limping out of the school, her knee covered in blood. Jaelyn found Samantha and borrowed her phone to call Sabika, but it went straight to voicemail. She tried again, over and over. She then began running from one student to another, asking if they had seen Sabika. She called her parents. “I can’t find Sabika!” she screamed. “I can’t find her!”

As word of the shooting spread, the terrified students scattered down Highway 6. Soon, news helicopters were hovering overhead. Local television stations broke into their regularly scheduled broadcasts to announce that an active shooter was at Santa Fe High School.

Half a world away, Aziz, Farah, and their children had just finished iftar, the evening meal at the end of the daylong fast. Aziz turned on the television to catch the latest news on Pakistan 92, and he saw on the ticker that there had been a shooting at a Texas school. He switched to CNN. On the screen was a photo of the same high school that Sabika had googled on her computer when she had first learned she was going to Santa Fe.

Aziz called Sabika, 24 times in a row. He finally called Jason, who by then had driven to the high school with Joleen. The two men had never spoken. Talking slowly so that Aziz could understand him, Jason said Sabika was missing, and as soon as he was given more information he would call back.

Jason, Joleen, Jaelyn, and other families who were still looking for their children were sent to a nearby school-district building that officials were calling a “family reunification center.” Periodically, a bus arrived with students who had been inside the high school since the police lockdown. The Cogburns watched each student step off the bus, hoping Sabika would emerge. At 1:30 that afternoon, the final bus arrived, carrying students who had been in the art room. Joleen asked if anyone had seen Sabika, and someone said she had seen Sabika go into the art classroom earlier that morning but hadn’t seen her come out. By then, only ten families remained at the reunification center. Jason got a call from a friend at the hospital. He ushered Jaelyn and Joleen into an empty room to tell them Sabika was dead. Jaelyn collapsed to the floor, and Joleen began screaming.

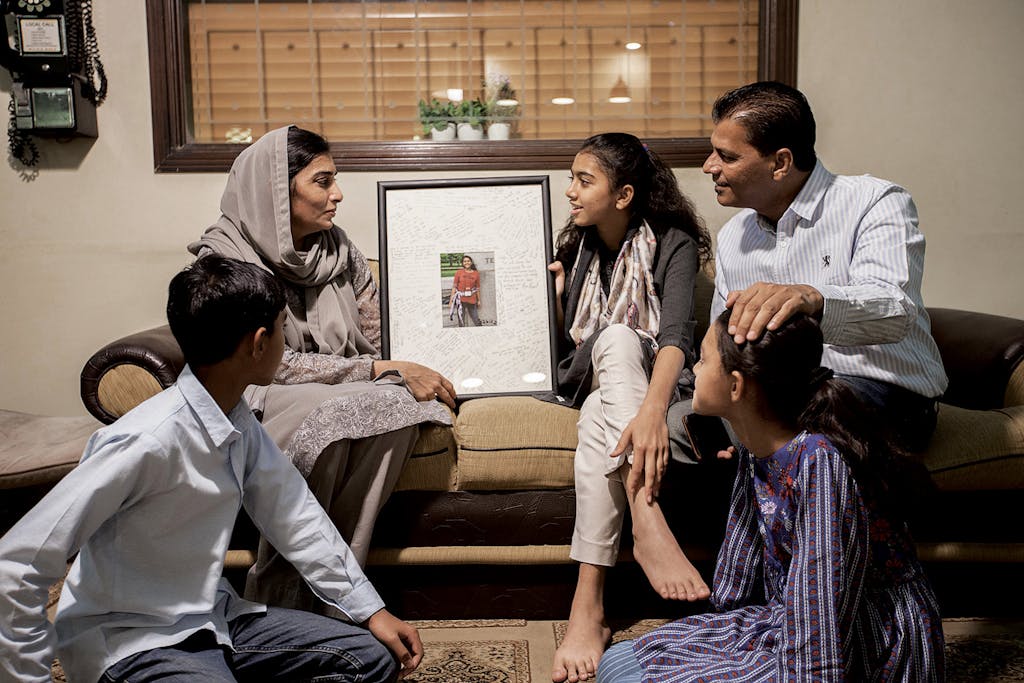

After the Cogburns drove home, Jason composed himself and walked outside to call Aziz, who was standing in his living room, surrounded by friends and relatives who had heard about the shooting. Farah sat with the children on the sofa. After speaking with Jason, Aziz lowered his phone. He turned to everyone in the room and said, “Sabika is no more.”

One by one, the men at the Sheikhs’ apartment clasped hands with him and quietly quoted the Quran. “Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un.” (“Verily we belong to Allah, and truly to Him shall we return.”) Farah kept her head bowed and said little.

In all, eight Santa Fe High School students and two teachers were murdered, and thirteen others were wounded. A seventeen-year-old junior at the high school, Dimitrios Pagourtzis, was arrested. He waived his Miranda rights and confessed to the killings.

Dimitrios had no criminal history. When he was younger, he was a member of a dance team at his family’s Greek Orthodox Church, and he had played defensive tackle on the Santa Fe High freshman and junior varsity football teams. He was a quiet kid. Many students had no idea who he was. Jaelyn and Sabika had never met him, but their friend Samantha had tried talking to him a couple of times; she once complimented the combat boots he often wore to school. But he had brushed her off, saying nothing.

Allegedly, Dimitrios was set off by an interaction with a sixteen-year-old student named Shana Fisher. That spring, Dimitrios had made several romantic advances toward Shana, and she had turned him down. A few days before the shooting, according to her mother, Shana had rejected Dimitrios in front of several classmates, humiliating him. In retaliation, Shana’s mother believed, he had decided to go on a killing spree.

That morning, Dimitrios wore his combat boots, a T-shirt that read “Born to Kill,” and a trench coat. Underneath the trench coat he carried his father’s Remington 870 shotgun and a .38-caliber handgun. He walked toward the school’s art lab, which was composed of two rooms, connected to each other by a walk-through supply closet. He stepped inside one of the rooms, where Shana was at work on a painting. He pumped the shotgun and began shooting. Shana was one of the first to die.

A few students leaped from their chairs and tried to run. A few others played dead. Still others, including the teacher, who was a substitute that day, made for the supply closet.

Sabika, who had been painting a landscape in the adjoining art room, wasn’t sure where the shots were coming from. She and others ran into the same supply closet. Sabika huddled in a corner, her lips moving. One girl would later say it looked as if she was praying.

To block Dimitrios’s access to the closet, Christian “Riley” Garcia, who was just fifteen, barricaded himself against the door that led to the first art room. Someone’s cellphone rang. “You want to get that?” Dimitrios shouted, and he shot through the door, killing Garcia. He flung open the door and continued firing. Bullets ripped into cans of paint on the closet shelves. The cans exploded. Kids in the closet screamed and tried to escape out of the opposite door.

Sabika was among those who attempted to flee. Dimitrios shot her in the right shoulder, the forehead, and the cheek. He then moved out into the hallway, taking aim at more students, another teacher, and a school security officer. Finally, thirty minutes after he started shooting, Dimitrios surrendered.

For days, mourners gathered on the high school’s front lawn. They formed prayer circles, held hands, and cried. They tacked hand-drawn posters (“Pray for Santa Fe,” “Santa Fe Strong”) to the trees and laid sympathy cards, photos, balloons, teddy bears, and flowers in front of ten white crosses that had been planted across the lawn. There was a candlelight vigil. Justin Timberlake, who was in Houston for a concert, visited the wounded in hospitals. Houston Texans football star J. J. Watt promised to cover the funeral costs of every victim. Texas politicians—Governor Greg Abbott, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Senator Ted Cruz—arrived. Donald Trump, who was already scheduled to visit Texas for fundraising dinners, announced that he would be meeting the victims’ families at Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base, twenty miles from Santa Fe.

A couple of days after the shooting, Jaelyn and her family drove to a funeral home to view Sabika’s body, which had been washed, wrapped in white linen sheets, and placed in a plain wooden casket. The bullet holes in her face had been patched over with cosmetics. Although the funeral home director asked the family not to touch Sabika, Jaelyn laid her cheek next to her friend’s cheek and sobbed.

Later that afternoon, she and her parents went to the Brand Lane Islamic Center in the Houston suburb of Stafford, where the Islamic Society of Greater Houston held a memorial service for Sabika. More than two thousand people showed up. The indoor worship area quickly reached capacity, so attendees hunkered outside, shedding their shoes and kneeling in the grass or dirt to say their prayers. Jaelyn, her head covered with a prayer shawl, told the crowd in a trembling voice that Sabika was “loyal to her faith and her country. She loved her family, and she couldn’t wait to see them. She was the most amazing person I’ve ever met. I will always miss her.”

Sabika’s casket was wrapped in the green-and-white flag of Pakistan and taken to the George Bush Intercontinental Airport, where it was loaded in the cargo bay of a 787 commercial jet airliner and flown to Karachi. A Pakistani honor guard, waiting on the tarmac of the Karachi airport, removed the casket from the airliner and placed it in a van, which transported it to the Sheikhs’ apartment. A throng of people was already gathered there. There was an uproar when the van appeared. Men surged forward to help carry the casket to the Sheikhs’ front door. Women wept into their scarves. Reporters and photographers pushed their way toward the Sheikhs’ apartment, where Aziz stood by the front door. When someone asked how he was feeling, he said, simply, “My heart drowns.”

A brief prayer service at Hakeem Saeed Ground, a public park, was attended by hundreds. Sabika’s body was then taken to a small cemetery, removed from the casket, and laid in a shallow grave, not far from her grandparents. Aziz turned her face to the east so that she always would be looking toward Mecca, and he helped toss dirt and small stones over her body. A few days later, he returned to the cemetery to watch workers install a headstone over the grave. Inscribed on it was a long passage from the Quran about nothing being worthy of worship except Allah. There were also two short sentences in English: “Pakistan’s Brave Daughter, the Dedicated Young Student Who Went to America for Study . . . May the Sky Shower Peace on Your Final Resting Abode.”

Throughout South Asia, Sabika’s death was front-page news. Reporters described her as Pakistan’s martyred daughter: an idealistic, promising young woman who had traveled to America with a message of peace, eager to experience the best of its culture, only to suffer its worst. Angry Pakistanis declared that the United States had no right to denounce other countries when it was plagued with its own version of terrorism. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, then Pakistan’s prime minister, visited the Sheikhs at their home. “Extremism is not the problem of any single country or region,” he told reporters afterward. “The whole world is affected by it.”

Aziz had never been politically active, but he gave interviews in which he begged President Trump to pass laws preventing American teenagers from obtaining firearms. “Sabika’s case should become an example to change gun laws,” he told Reuters.

He spoke by phone to attorneys from Everytown for Gun Safety, a New York–based nonprofit, and he and Farah eventually agreed to join a lawsuit along with other Santa Fe parents who had lost children in the shooting. The lawsuit, which was modeled on a similar suit successfully filed by parents of victims of the 2012 school shooting in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, accused Dimitrios’s parents of criminal negligence for not safely storing their guns.

“No other parent should ever have to experience this unbearable grief,” Aziz and Farah stated in a press release put out by Everytown. “Sabika’s picture is in front of our eyes every single moment, and her voice and laughter echo in our ears. For a mother and a father, this trauma and mourning stay until their last breath.”

In the months that followed, there was little that soothed the Sheikhs’ grief. Farah would often forget that Sabika was gone. When she set the table for a meal, she would include a plate and silverware for Sabika. When she walked past Sabika’s room, where a couple of her books, Kite Runner and Fangirl, remained on the nightstand, she would hear Sabika talking. At night, she would dream that Sabika was alive and happy and finishing her school year in Santa Fe. Then she would jolt awake and weep into her pillow, doing her best to stifle the noise so she wouldn’t wake the children.

Every day, Aziz would visit Sabika at her grave site. At the cemetery’s front gate, he would purchase a bag of red rose petals from a flower vendor, and he would sprinkle the petals over the dirt and stones that covered Sabika’s body. He would pray to Allah, his left hand over his right, and afterward he would gaze at the grave and make a promise to his daughter: “I will be back tomorrow.”

Sometimes in the late afternoons Aziz would ask Farah, Saniya, Soha, and Ali to accompany him to the rooftop of their apartment, where Sabika loved to play badminton. “You must remember that Sabika is with Allah,” he would remind the children. “She is at peace.”

There would be silence, and the children would try not to cry.

The Cogburns turned to their own church for solace. In late May, Joleen asked the senior pastor, Greg Lackey, to hold a memorial service for Sabika. It was a peculiar request: a memorial for a Muslim at an evangelical church. But during Sabika’s time in Santa Fe, the congregation had come to adore her, so Lackey agreed to hold the service on a Wednesday night.

More than one hundred people attended. They sang Sabika’s favorite contemporary Christian songs, “Reckless Love” and “What a Beautiful Name.” Lackey spoke briefly, as did Joleen, Jason, and Jaelyn. Photos of Sabika were displayed, and various members shared their favorite memories of Sabika.

After the service, Jaelyn was in better spirits. But as the days passed, she had trouble focusing on anything but Sabika’s death. She sent texts to Farah, telling her that she felt overwhelmed, and one evening, she called Farah just to hear her voice. But Farah sounded so much like Sabika that Jaelyn broke down.

Jaelyn told her mom that her life was without joy. Joleen recited a famous passage from the book of Psalms: “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning.” The Bible, she said, teaches that God numbers everyone’s days, and he knows their beginnings and ends.

Jaelyn, though, was haunted by one thought in particular: if only. If only she’d stayed with Sabika in the green pickup in the parking lot on the morning of May 18, Sabika likely wouldn’t have been in the art room when the shooting started. It’s possible that her life would have been spared. Why, Jaelyn asked herself over and over, hadn’t she talked with her best friend a little longer? Why hadn’t she stayed with Sabika?

Like Farah, Jaelyn was tormented by a recurring dream: She would travel to Karachi to see her friend, but each time Jaelyn tried to approach her, Sabika would turn and run away. Sabika’s face looked as if it had been burned. “I don’t want to talk to you!” Sabika would shout. “Leave me alone!” Jaelyn would run after her, but Sabika would always disappear.

In her bedroom, Jaelyn spent hours in prayer, begging God to “make a way” for her, and in June, just after her sixteenth birthday, she told her parents that God had heard her prayers.

“What does God want you to do?” Joleen asked.

Jaelyn said that God had put it on her heart to move to the Central American country of Belize.

A year earlier, before Sabika arrived in Santa Fe, Jaelyn had embarked on a ten-day mission trip with her church’s youth group to the impoverished Belizean village of Teakettle. (Joleen went along as a chaperone.) She volunteered at an orphanage and worshipped at a tiny, tin-roofed Baptist church. When the trip was over, Jaelyn told her mom she wanted to return someday.

Now she was convinced God was calling her back to Belize. Just like Sabika, she told her parents, she wanted to live for a year with host parents and attend the local high school. She wanted to volunteer at the orphanage and spread a message of love to the Belizean people she met.

“We knew that some of our friends would say, ‘Come on, you can’t let your daughter go over there all by herself,’ ” said Jason. “But we also knew that if Jaelyn stayed around Santa Fe, nothing would get better. The only way one gets through tough times is to serve other people.”

And so, in August, Jaelyn and Joleen flew to Belize, rented a car, and drove to a part of the country that Caribbean-loving tourists rarely see: its interior, thick with rain forests and tiny villages, where dirt streets are lined with shanties and smoke from cooking fires lingers in the air.

When they arrived in Teakettle, Joleen and Jaelyn were greeted by Zayra Jones, whose brother Job was the pastor of the tin-roofed church. Zayra, a single mother of three, gave them a tour of her small cinder-block home. In her living room, an electric fan dispatched a thin breeze across a pair of sagging brown couches, and propped against a chair were a weed cutter and two cans of motor oil. Zayra escorted Jaelyn to her bedroom, which was just big enough to fit a bed, a nightstand, a lamp, and a fan. She showed Jaelyn the bathroom and explained that if she wanted to take a shower she would need to fill a bucket of water using a hose that ran through a hole in the wall. To wash her clothes, she would have to scrub them at a nearby creek. There was spotty phone service and no internet. Meals usually consisted of tortillas, beans, rice, and plantains picked from a backyard tree.

Jaelyn unpacked her suitcase. On her bed she placed a pillow imprinted with a photo of Sabika, and above the nightstand she taped Bible verses her mother had handwritten for her. Joleen stuck around for a couple of weeks to help her daughter settle in, sleeping down the road at a cheap motel atop a gas station. Finally, she realized there was nothing more she could do. She and Jaelyn said a long prayer together, and Joleen drove away.

Jaelyn settled into a new routine. In the mornings, she ate a plantain for breakfast, put on her school uniform (a blue dress with white knee socks and black slip-on shoes), walked a mile to a bus stop by the main road, and waited for the school bus that would take her to Belmopan Baptist High School, about seventeen miles away. Some three hundred teenagers attended the blue two-story building at the end of a gravel road. The rooms were furnished with secondhand chairs and desks. Because bathroom supplies were limited, Jaelyn had to bring her own toilet paper to school.

She began each school day by singing the Belizean national anthem and reciting the school pledge along with her classmates, and she took a standard slate of courses. After school and on Saturdays, she visited the King’s Children’s Home, a low-slung building that’s home to some fifty children, ranging in age from five to eighteen. Jaelyn was only allowed to associate with other girls, with whom she played card games or volleyball in the courtyard or simply talked about what life is like in America.

On Sundays after church, Jaelyn liked to go swimming in a river with Zayra’s children. At the end of each day, she called Joleen, she read her Bible, and she drifted off to sleep.

As the weeks passed, Jaelyn continued to experience flashbacks from the day of the shooting. Whenever she heard a fire alarm or a siren, her body trembled involuntarily. One afternoon, when she was shopping at a convenience store in Teakettle, a man with a rifle and an ammo belt walked in. Jaelyn was seized by a panic attack, unable to breathe. Another day, she was sitting in class and, unprompted, began to cry uncontrollably. She was ushered to the principal, who asked if she was being bullied by other students. “No,” said Jaelyn. “I’m sorry. I just can’t talk about it.”

In December, the school announced its annual poetry contest, and Jaelyn decided to write about Sabika. It would be the first time she told anyone at the school about the shooting. The day of the competition, the entire student body gathered at the outdoor chapel to hear the contestants read their work. The themes were, for the most part, typical of teenage life: a girl’s lamentation about other girls who pretend to be friendly but really aren’t; a boy’s adoration of his brother. When it came time for Jaelyn’s reading, she shuffled to the stage and stood in silence, rivulets of tears forming across her face. A minute passed. Then another. Jaelyn finally looked up and announced the title of her poem, “Why I’m Here.” She began:

I’m an American girl in Belize living her life alone.

You’ve never seen me. I’m unheard of and unknown.

She described her friendship with Sabika.

I swear I’ve never been closer to a person. Nor will I ever be.

She was like an angel sent from God and came to set me free.

She recounted the shooting.

A boy went to school with a gun in his hand.

He started shooting. And I just ran.

She shared the despair that still haunted her.

I know what it’s like to hurt, to have pain, to gain, to lose.

I know what it’s like to live when death has come so close.

When she finished, her fellow students gave her a standing ovation. Jaelyn broke into tears again and slowly walked back to her seat.

In early March, as he had done every day since Sabika’s murder ten months earlier, Aziz climbed into his green Corolla and paid a visit to his daughter. He sprinkled rose petals across her grave. He prayed over her body. He promised he would return the next day. But when he arrived home, he told Farah it was time to make a change. On the anniversary of Sabika’s death, he would fly the family to Saudi Arabia for Umrah, a pilgrimage to Mecca. And later, he wanted to take them to visit Santa Fe. He was worried that Sabika might feel abandoned if they left Karachi, but he said she would understand if he didn’t come see her for a week or two.

Farah was quiet. She feared that the family would experience anti-Muslim hostility in America. But like Aziz, she knew that a visit to Santa Fe might ease their sadness. So she emailed Joleen. She mentioned that they wanted to see the high school Sabika attended, the library where she volunteered, even the bedroom where she stayed when she lived with the Cogburns. And, of course, they wanted to meet Jaelyn.

Joleen was thrilled. She wrote back and told Farah that the Sheikhs could stay at their house as long as they wanted. She and Jason would love to host them, and she’d fly Jaelyn in from Belize for a few days.

Joleen called Jaelyn, who was also elated. They talked about how the trip could be healing for everyone. Then the conversation naturally shifted to Jaelyn’s future—specifically, what she planned to do when the school year concluded. Joleen and Jason had assumed Jaelyn would return home. They had suggested she take dual credit classes at a junior college near Santa Fe. Or she could resume homeschooling. (Jaelyn had told her parents that she could never again walk the hallways of Santa Fe High School.)

Jaelyn, though, had already settled on another idea. “I believe God is calling me to stay in Belize,” she told her mother. Since the poetry competition, she had been making new friends. And she felt like she was making a difference at the orphanage.

“You really want to stay?” Joleen asked. “For another year?”

Jaelyn calmly explained that she was getting the chance to do for others what Sabika had done for her. She was keeping Sabika’s spirit alive.

“Is there anything better I could do with my life?” Jaelyn asked. “Anything?”

This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Sabika’s Story.” Subscribe today.