An attorney representing the Horry County School District collaborated with a builder to cra…

A former Horry County Schools spokeswoman insists she was fired from her job because she provided media outlets with public information that HCS officials did not want her to release, according to a lawsuit filed this week.

Teal Britton, who worked for HCS from 1993 until her termination in 2020, filed the wrongful termination suit in Horry County on Wednesday. In her lawsuit, Britton contends that she drew the ire of top HCS officials because she released records about the district’s controversial school construction program in response to S.C. Freedom of Information Act requests.

“Plaintiff was terminated in violation of the following clear mandates of public policy found within the South Carolina Freedom of Information act and South Carolina Procurement Code,” the lawsuit states.

Horry County Schools spokeswoman Lisa Bourcier said the district wouldn’t comment on the lawsuit, but former school board member Holly Heniford said board members weren't happy with Britton because they needed someone to speak for them in a timelier manner than she did. Heniford was no longer on the board when Britton was terminated but recalled the board’s frustrations. Heniford wasn't sure of the exact reasons Britton was fired.

“We were not getting questions answered in a timely fashion from the district office, if at all,” Heniford said. “We hired Lisa [Bourcier] so we could make sure the information got out in a timely fashion and we had more control over that. The district was throwing us under the bus. Folks would say stuff about the board that needed to have a comment.”

The district’s building program came under scrutiny after HCS leaders deviated from their normal procurement practices to choose a builder for five new schools.

The company that received the contracts, Firstfloor K-12 Solutions, had responded to the district’s solicitation for conceptual design services in 2013 but wasn’t chosen for the work.

The following year, the district sought qualified vendors for design services and production architecture for the new schools. However, Firstfloor did not respond to the HCS request for qualifications.

Yet members of the school board and district legal counsel met to discuss a plan to build “energy positive schools,” a concept touted by Firstfloor, according to the lawsuit. The idea behind these schools is that they should generate more energy than they use.

For more than two years, Horry County Schools fought against giving school builder Firstfloo…

The lawsuit provides a timeline of the events that led to Britton's firing.

At an Oct. 20, 2014, board planning retreat, then-HCS Board Chairman Joe DeFeo invited Firstfloor CEO Robbie Ferris to pitch his proposal for the new schools.

The district ultimately abandoned its RFQ process, prompting then-HCS Superintendent Cindy Elsberry to voice ethical and legal concerns about the board veering from its normal procedures.

“The superintendent complained that ‘her advice had gone unheeded,’” Britton’s lawsuit states. Elsberry announced her resignation on Nov. 17, 2014.

Rick Maxey, the district’s chief operations officer, was named interim superintendent.

“A new RFQ was then published by agents of the district that was particularly tailored [to] Firstfloor,” Britton’s lawsuit states. “Firstfloor also contributed to the drafting of the RFQ. The Board Chairman for HCS at the time, Joe Defeo, also participated in drafting the RFQ. Mr. Defeo … did not have construction or architecture experience.”

Heniford blamed the school board’s attorney, Keith Powell, for letting Ferris have a hand in drafting the RFQ.

Horry County Schools’ former executive director of facilities, Mark Wolfe, is suing the dist…

“I wasn’t involved with that process, but the attorney allowed the conversation. He did not have to talk to Robbie and the attorney knows who he represents, or should know,” Heniford said. “The attorney works for the whole school board. Even if he was directed by one person to work on this contract with Robbie, he shouldn’t have, because he was hired to work for the whole school board.”

The board dropped the interim tag from Maxey’s title in 2015 “without an executive search or competitive interviews,” according to Britton’s lawsuit.

Britton maintains DeFeo told her on multiple occasions that Maxey could remain superintendent as long as he did as the chairman told him.

DeFeo then handpicked the five school board members who would serve on the district's procurement selection committee that supported Firstfloor as the managing architect for the school construction project, the suit said. In November 2015, Firstfloor was awarded the contracts to construct the five new schools.

“All five contracts were signed by Mr. Defeo who did not have signature authority to sign for capital improvement projects for the district,” according to Britton’s lawsuit. “The authority for these matters instead rested with fulltime District Administration. District Administration did not have an opportunity to review the final versions of the contracts prior to there being signed. The contracts were also signed before a formal board vote occurred.”

Heniford defended Defeo’s actions, reasoning that had the board voted down the contract, Defeo’s signature would have been meaningless.

“There’s nothing wrong with that,” Heniford said. “If we voted it down, then the signature’s void. His signature’s not valid without the vote. He can sign all the contracts he wants to. They’re not valid unless the board votes on ‘em.”

The former head of Horry County Schools’ facilities department accused Superintendent Rick M…

Once the contracts were signed, DeFeo’s former employer, Southern Asphalt, was named a subcontractor on the project, according to Britton’s lawsuit.

"If you remember how quickly we were going to build these things and the manpower to make it happen, there were only certain companies that could meet that," Heniford said. "If it happened to be Joe’s friend, it happened to Joe’s friend. It was huge. The qualified people that were available were what they were going for."

Although Britton was not involved in the contractor selection process, she did field public records requests about the project.

“The district was inundated with Freedom of Information and general media requests about its building program from 2014 onward,” the lawsuit states. “Mr. Defeo positioned himself as a spokesperson for the building program and spoke freely with members of the news media about it. Those media outlets would often file records requests thereafter to validate Mr. Defeo’s comments. Mr. Defeo asked Plaintiff and other individuals in the communications department to apply excess fees to discourage requests for information. Mr. Defeo told the Plaintiff that he intended to deter requests through expensive fulfillment fees.”

Heniford said DeFeo wanted the district to receive compensation for what it cost them to fulfill FOIA requests.

“I heard Joe talk about raising the FOIA fees because of what it was costing us to pull all this paper together and send it to people,” Heniford explained. “That’s what I heard. But we were looking at how to recoup the time and energy of employees that we had to pull off their jobs to handle these FOIA requests. How do you calculate that? That’s’ the conversation I heard.”

In December 2015, Britton was interviewed by the State Law Enforcement Division (SLED) during its investigation of the building program. The lawsuit states that the investigation remains open, though a SLED spokesman could not immediately be reached for comment.

Two years later, Britton angered DeFeo when she responded to requests about whether HCS staff was able to review Firstfloor’s contracts before they were signed, according to the lawsuit. She said district staff was “largely excluded from the contracting process.”

“This angered Mr. Defeo, and when he was interviewed by a media outlet about it, he falsely stated that Plaintiff had ‘misunderstood,’” the lawsuit states. “Shortly thereafter in or around, second incident occurred where Plaintiff drew the ire of Mr. Defeo and allied board members for releasing a statement from HCS administration in regard to media requests about the absence of records pertaining to subcontractors and their fees for the building project. That statement from administration indicated an opinion that the public had the right to know how the public monies were being spent on contractors.”

A company that supplied construction materials for Horry County’s five new schools filed a s…

The contractors’ records led to a dispute with Firstfloor, according to the lawsuit.

“Firstfloor’s contracts with HCS said they were responsible for maintaining proper records on their subcontractors and providing them to the District upon request,” the lawsuit states. “The CEO of Firstfloor told the Plaintiff: ‘I can hire who I want and I can pay them what I want.’ Firstfloor insisted it would not provide records for subcontractors and Defendant HCS ultimately did not press the matter. The authority to press the matter on FOIA production and transparency lied with Joe Defeo as the signatory to the contract. The Board thereafter consistently declined to press for transparency with respect to the terms of the contracts for subcontractors hired by Firstfloor.”

Britton said that led to her receiving requests from lawyers representing subcontractors who said they had not been paid for work on the new schools.

“The district had no means to validate if the named subcontractors or materials at issue had been used because the district was not privy to the relevant records,” the lawsuit states. “These two incidents, where Plaintiff performed her job in a way that complied with the Freedom of Information Act, resulted in Mr. Defeo and his allies on the Board pressuring the Superintendent of HCS to change Plaintiff’s position.”

Britton was named director of internal communications and staff engagement later in 2017.

“The context of Plaintiff’s position change indicates that the motive of doing so was to reduce the frequency upon which she would be called upon to reply to public information requests appropriately, lawfully, and dutifully,” the lawsuit states.

The board also created the position of director of external strategic communications and community engagement around the same time. Bourcier was hired for that job, and began performing job duties that previously fell to Britton, including handling FOIA requests and questions from the news media.

“Lisa would have never been hired if [Britton] had been more transparent,” Heniford said. “There were things that were thrown at the board from the public and the media and the district office wasn’t responding in a timely fashion. They weren’t responding and we would ask them to respond and they weren’t responding.”

Firstfloor Energy Positive, along with Horry County Schools and four other companies are bei…

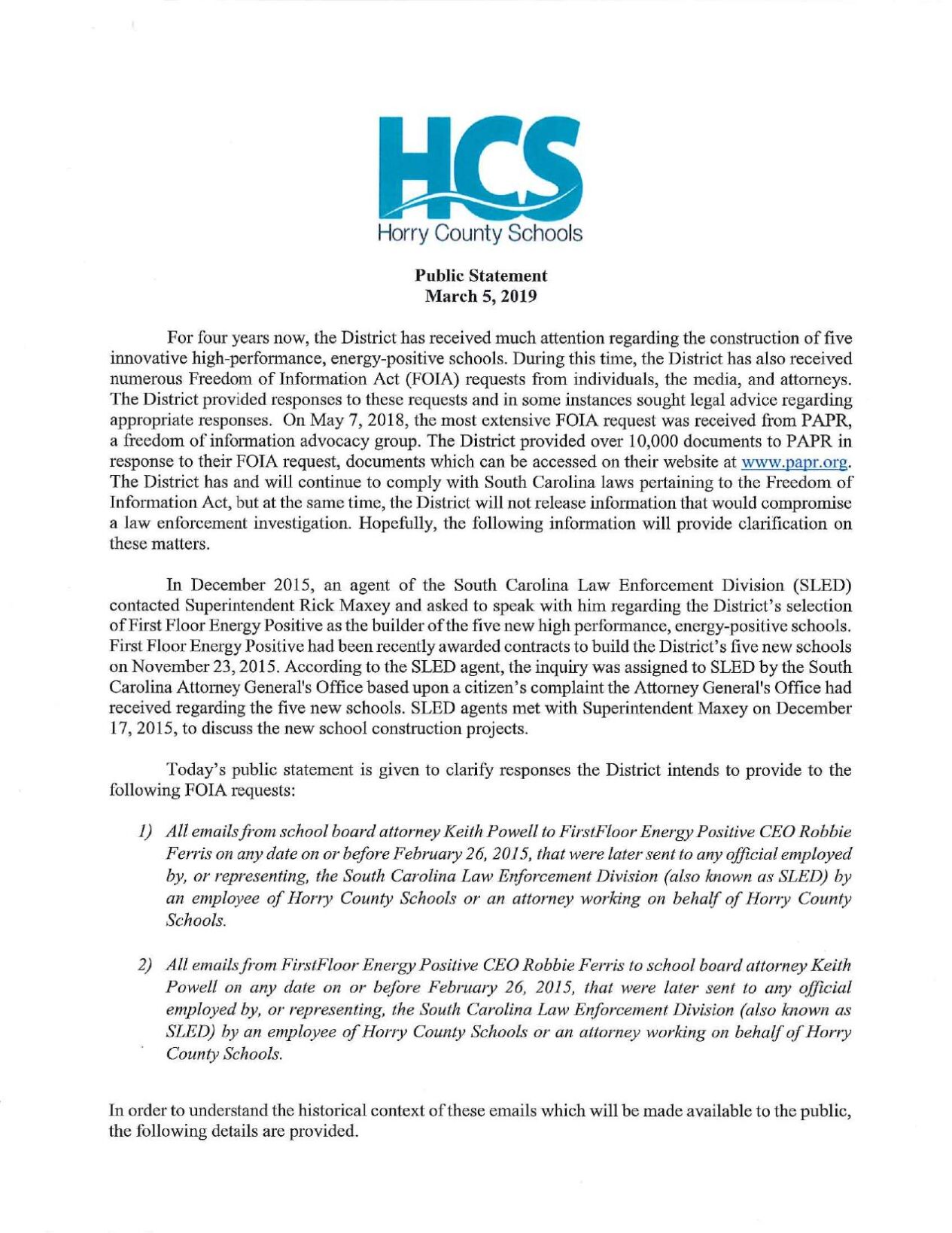

DeFeo died in 2018. Britton contends that she tried to go along with the changes in the department. But in March 2019, she discussed concerns with her supervisor, staff attorney Kenny Generette, after viewing a statement from the district about the building program.

That day, the district acknowledged that the program was being investigated by SLED and issued a statement in response to inquiries and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests from MyHorryNews.com. (You can click here to read the district's statement confirming the SLED investigation.)

In her lawsuit, Britton said Maxey criticized her for sharing her concerns.

“After berating Plaintiff, the Superintendent would not speak to Plaintiff again until June 2020,” the lawsuit states. “Plaintiff thereafter observed a negative change in the way she was treated by her supervisory chain.”

Britton contends that district officials began to nitpick her work and she was criticized for missing an assignment while she was out sick with bronchitis in August 2019. She maintains she was later excluded from important meetings that she needed to attend to do her job. On Feb. 12, 2020, Britton was reprimanded for not responding to a message that was left on her colleague’s voicemail, according to the lawsuit.

The following month, Britton provided statistical information about HCS’s recent graduating classes to a Coastal Carolina University official. Britton said she released that information because it was public.

Britton insists her supervisor was aware of what she had done but later denied it, according to the lawsuit. On May 27, 2020, Britton was told she could resign or be terminated.

“Plaintiff expressed on May 29, 2020, that she would not resign because she had not done anything to warrant a forced resignation or termination,” the lawsuit states.

She did not receive her termination notice until Aug. 6, 2020, according to the lawsuit. She requested a grievance but the board voted to deny her a grievance hearing.

Britton is the second former HCS staffer to file a lawsuit tying the building program to a firing.

Mark Wolfe, the former head of Horry County Schools’ facilities department, had accused Maxey of wrongfully terminating him after he opposed corruption in the district’s most recent school construction program, according to court records.

Correction: this story has been updated to show that Holly Heniford did not know why Teal Britton was fired but could only speak to school board members' frustrations.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.