Are Your Team Members Lonely?

Despite the prevalence of team-based collaboration in the workplace, many employees feel isolated on the job.

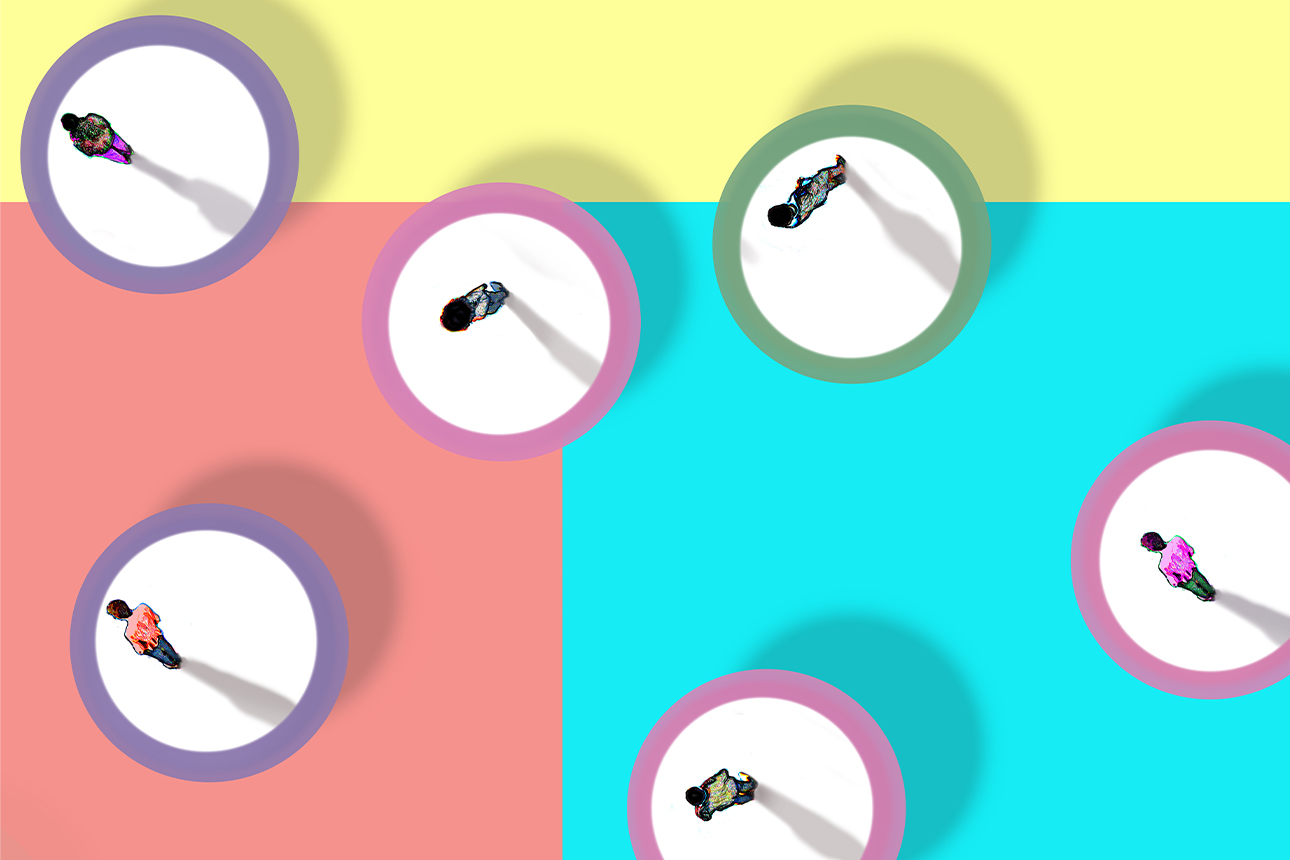

Image courtesy of Gary Waters/theispot.com

While loneliness is often thought of as a personal issue, it is an organizational issue as well. A lack of social connection — whether with friends, family members, or coworkers — can have serious consequences. It is associated not only with health problems,1 including heart disease, dementia, and cancer, but also with poor work performance, reduced creativity, and flawed decision-making.2 Quite simply, people who feel lonely cannot do their best work, which means that teams with lonely members are not operating at their peak levels either.

You might think that working on a team would stave off loneliness by fostering a sense of community and camaraderie. But in our research, we have found that the composition, duration, and staffing of teams can trigger or exacerbate feelings of social disconnection in the workplace. Therefore, we caution managers to view loneliness as a systemic and structural problem that may require a new approach to teamwork.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Team Members Are Feeling Isolated

To explore the relationship between the way teams are designed and loneliness, we have undertaken two research studies involving nearly 500 global executives and informal interviews with many other managers through our executive education and consulting work. In our first survey study of 223 executives, conducted in December 2019 and January 2020, we found that, even prior to the major shift to working from home and social distancing brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, people were struggling with feelings of social isolation at work. For example, 76% reported that they had difficulty making connections with their work teammates, and 58% agreed with the statement “My social relationships are superficial at work.” Yet these executives were serving on an average of three teams at the time. In examining the features of those teams, we saw that aspects such as low membership stability and lack of role clarity were significantly correlated with greater expressions of loneliness among respondents.

The problem of loneliness has been further fueled by the pandemic. When we sampled a different group of almost 275 global executives in April 2020, we again found strong prevalence of teamwork: 72% were working on two or more teams at the time, with nearly 20% working on five teams or more.3 Respondents also conveyed feeling lonely and isolated. Most were continuing to work with their teammates remotely. One noted that the biggest challenge was in trying to “connect on a personal level with coworkers.” Certainly, working remotely instead of face-to-face can by itself undermine social connections.4 But that is not the whole story, so resuming in-person work won’t fix the loneliness problem. Modern team design is an underlying factor that must be addressed. Let’s look at how it has changed in recent years and what the downsides are.

The Costs of Modern Team Design

High-performing teams achieve three distinct types of success: excellent work products, member growth and development, and positive intrateam dynamics. This model of team effectiveness, developed by Harvard psychologist Richard Hackman and others more than 30 years ago, is still considered the gold standard.5 However, it was built on studies of teams back when they were typically defined by stable (usually full-time) membership, robust roles, a common mission, interdependent work, sustained activity, and a manageable size.

Since then, the ecology of teams has changed.6 As corporate work has become more global, dispersed, and round-the-clock in nature, teams have been asked to grow in scope, to be more dynamic and flexible, and to work more cost-effectively.

Consequently, four features of contemporary teams have emerged:

Fluid composition. As teams have sought to minimize overhead and increase flexibility, many have been designed to include a fluid set of members who roll on and off the team as the project needs demand. A telltale sign of a fluid team is when each member gives a different answer as to who is on the team7 or when answers change over the course of a team’s life, something we have seen in our own research when we try to nail down who is going to participate.

Modularized roles. As teams have sought to become more efficient and scalable, roles are sometimes modularized into discrete components or skills needed (“someone savvy with the new billing system,” for instance, or “a representative from sales”). This allows for job sharing, as well as the possibility of continuous, 24-hour work if individuals in different time zones can perform the same role on a rotating basis.

Part-time commitment. In an attempt to get more out of each employee, many organizations stock their teams with part-time members who simultaneously serve on more than one team. This means that, on any given team, the members are only partially committed in terms of their time and effort. It also means that members are constantly juggling competing demands and timetables from other teams.

Short duration. To quickly respond to changes in the marketplace, many teams are expected to form and disband within short intervals, such as a few weeks. This is particularly true in agile teams, but other teams may also last for only a brief period, such as those attached to business development or market strategy projects.8

These team features often do, as intended, make organizations faster, more flexible, and more efficient. So organizations are finding it easier to increase and improve output, the first criterion for team effectiveness. Moreover, employees may experience greater autonomy, more flexibility, and increased exposure to a diverse set of projects and colleagues because of their team arrangement. Those who do may benefit through growth and development, the second criterion of team effectiveness.

But what about the third criterion, positive intrateam dynamics? Such dynamics can aid team survival, despite the demands that collaborative work tasks and high-pressure environments can bring.9 People who feel positively connected to each other are more likely to stick together through adversity and provide the type of support that reduces burnout and turnover.10 Furthermore, creativity and knowledge transfer can improve when teams have a chance to bond and build trust together.11

Unfortunately, the four features of modern teamwork are unlikely to generate these positive dynamics. They tend to foster shallow, narrow, and ephemeral relationships rather than true human connections. Creating positive intrateam dynamics takes time and effort — resources that are in short supply when teams rapidly form and disband, and members dip in and out. (See “Four Ways That Teams Foster Loneliness.”)

One issue that can exacerbate loneliness is a discrepancy between what people think they should feel (camaraderie and connection), especially if they are serving on many teams, and what they actually feel. Often, lonely individuals think it is “just them” — that their experience is due to their character traits rather than their situation.12 But it isn’t just them; their experience is common. In the workplace, therefore, the answer to loneliness is not to place people on more teams, which would make it even harder to move beyond shallow connections, but to change how teams are formed.

What Managers Can Do About Loneliness

Not every team or organization is structured in a way that undermines social connections. Furthermore, not every employee working on teams, even ones with each of the four design features prevalent today, will experience what psychologists call a “relational deficiency.”13 Individuals’ specific needs for personal connection at work vary based on factors such as personality, cultural background, and stage of life. But given how widespread the problem of employee loneliness has become, it is incumbent on managers to recognize and address structural drivers of isolation where they exist.

Here, we provide some suggestions for tackling these issues.

Start measuring the problem. Due to the salience of quantifiable team-performance markers such as speed, productivity, and cost efficiency, it is easy to overlook harder-to-assess indicators like whether team members are well integrated and supportive. We all know the business adage “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” So one way for managers to combat loneliness in their organizations is to start benchmarking and tracking its presence more systematically.

Research studies offer some simple survey tools that can help,14 but managers should also talk to their employees to develop their own “sensors” for the quality of connections and degree of loneliness among their teams. This kind of proactive effort is especially important in remote teamwork contexts because, as one manager we spoke with commented, “The level of empathy and care has a certain ceiling when all you have are faces on the screen.” Once managers start assessing the base rates of loneliness in their organizations, they can address any worrisome results they find.

Identify and nurture core teams. One potential intervention involves creating core teams (or “home base teams”), particularly for those employees who crave deeper connections to their colleagues. A core team could be defined by structural factors, such as where people spend the majority of their time, or by social factors, such as shared affinities and interests. In earlier research, we found that participants associated core teams with important psychological and social benefits. One participant described his core team as one in which members shared comfortable similarities in background and work ethic. Others called their team their “authentic community” and a collection of “my favorite colleagues.”15

For a core team to trigger such positive connotations, it should include pro-relationship design elements such as a shared identity, a longer duration, and a common mission. In this type of environment, more enriching relationships are likely to grow. To protect and nurture core teams, the organization must align the human resources systems and workflows accordingly. For example, job descriptions could be written to enable employees to dedicate 50% or some other substantial percentage of their time to one core team. When appropriate, projects could also be designed to support the creation of a stable team roster with well-defined roles and a time horizon lasting months or years instead of weeks.

Engage team leaders in combating loneliness. Given the nature of loneliness and the complexity of organizational life, we cannot expect individual employees to “cure” their loneliness on their own — even if a monitoring process is in place and core teams are available. To solve a systemic issue such as workplace loneliness, a systemic response is required. That means leaders and managers who control team designs and placement must be asked to take more responsibility for employee well-being and social interconnection. This need not be onerous or heavy-handed — it can be as simple as a periodic check-in with the team on how members are feeling. But team leaders must be sincere and patient in their efforts to get people to open up, since loneliness is not something that people usually want to discuss. A good way to remove any perceived stigma is to make such check-ins a normal part of the team’s processes.

It is also important to recognize that team leaders’ authority and access to information enable them to tackle some of the issues that arise between teams. Take, for example, the common situation where firefighting on one team constantly pulls shared members off other teams’ projects, impeding their ability to form necessary connections. Team managers need not be responsible for teams other than their own, but they should take shared responsibility for employees’ social welfare. That includes being open to discussions about spillover effects and being willing to take action, perhaps by changing team membership or working with leaders of members’ core teams to better align project schedules. Organizations can reinforce this shared responsibility by evaluating and compensating team leaders not just on team output but also on the degree to which they foster positive interpersonal dynamics both internally and across the organization.

Seemingly beneficial organizational structures can incur hidden costs, as our research shows, degrading the psychological well-being of employees and the social fabric of the workplace. Leaders should consider carefully if it is necessary or even desirable to incorporate elements such as fluid composition, modularized roles, part-time commitment, and short duration in their team designs. For the sake of all those lonely workers — and ineffective teams — out there, we encourage leaders to proactively monitor and foster satisfying connections among employees. The promise of high-performing teams still exists, but it takes a sensitive, deliberate approach to designing teams to realize that potential.

References

1. E. Carson, “How Loneliness Could Be Changing Your Brain and Body,” CNET, June 15, 2020, www.cnet.com; J. Holt-Lunstad, T.B. Smith, and J.B. Layton, “Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review,” PLoS Medicine 7, no. 7 (July 2010) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316; V. Murthy, “Work and the Loneliness Epidemic,” Harvard Business Review, The Big Idea (September 2017): 3-7; and S. Cacioppo, A.J. Grippo, S. London, et al., “Loneliness: Clinical Import and Interventions,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 10, no. 2 (March 2015): 238-249.

2. H. Ozcelik and S.G. Barsade, “No Employee an Island: Workplace Loneliness and Job Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 61, no. 6 (December 2018): 2343-2366.

3. M. Mortensen and C.N. Hadley, “Life Under COVID-19 Survey Results Report,” May 12, 2020, www.covidcoping.org.

4. K. Vasel, “The Dark Side of Working From Home: Loneliness,” CNN Business, April 30, 2020, www.cnn.com. See also J. Mulki, F. Bardhi, F. Lassk, et al., “Set Up Remote Workers to Thrive,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51, no. 1 (fall 2009): 63-69.

5. J.R. Hackman, “Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2002).

6. R. Wageman, H. Gardner, and M. Mortensen, “The Changing Ecology of Teams: New Directions for Teams Research,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 33, no. 3 (April 2012): 301-315.

7. M. Mortensen, “Constructing the Team: The Antecedents and Effects of Membership Model Divergence,” Organization Science 25, no. 3 (May-June 2014): 909-931.

8. N. Scheiber, “The Pop-Up Employer: Build a Team, Do the Job, Say Goodbye,” The New York Times, July 12, 2017.

9. M. Haas and M. Mortensen, “The Secrets of Great Teamwork,” Harvard Business Review 94, no. 6 (June 2016): 70-76.

10. C.N. Hadley, “Emotional Roulette? Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Emotion Regulation Outcomes From Coworker Interactions About Positive and Negative Work Events,” Human Relations 67, no. 9 (September 2014): 1073-1094.

11. A.C. Edmondson, “The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth” (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

12. Vasel, “The Dark Side.” This tendency is also seen in social media, where depression and self-blame can occur when connections to others are high but fulfilling relationships are not. A. Walton, “6 Ways Social Media Affects Our Mental Health,” Forbes, June 30, 2017, www.forbes.com.

13. S. Wright and A. Silard, “Unravelling the Antecedents of Loneliness in the Workplace,” Human Relations OnlineFirst, Feb. 21, 2020, https://journals.sagepub.com.

14. See, for example, G.W. Marshall, C.E. Michaels, and J.P. Mulki, “Workplace Isolation: Exploring the Construct and Its Measurement,” Psychology & Marketing 24, no. 3 (March 2007): 195-223; and D.W. Russell, “UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure,” Journal of Personality Assessment 66, no. 1 (1996): 20-40.

15. J. Wimmer, J. Backmann, M. Hoegl, et al., “Spread Thin? The Cognitive Demands of Multiple Team Membership in Daily Work Life,” LMU-ILO working paper, Munich, Germany, 2017.

Comment (1)

Guy Enemare