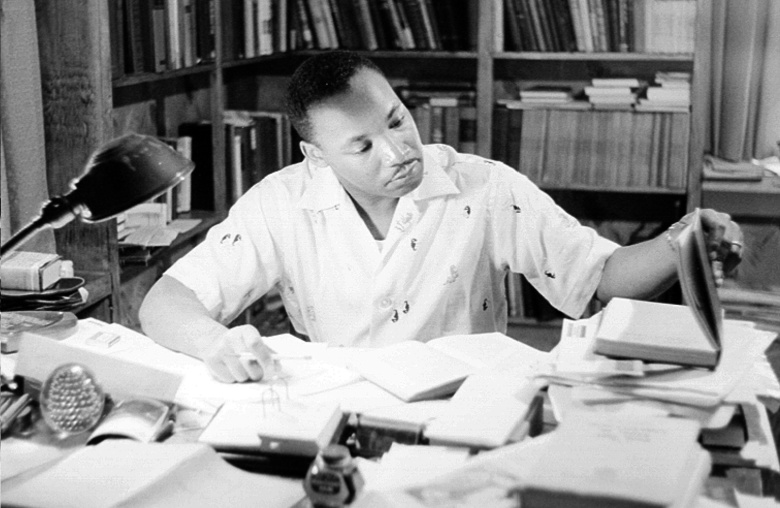

Martin Luther King Jr. at home in 1956 in Montgomery, Alabama. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

The story of the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, is widely told, so much so that Rosa Parks, who inspired it, and Martin Luther King Jr., who led it, are now two of the best-known figures in U.S. history. Less known is how the events of that protest turned King into a bestselling author.

On January 23, 1957, more than a year after the boycott had begun, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered an end to segregation on Montgomery’s buses. Soon New York City editors were flooding King with letters suggesting that he write a book.

Eugene Exman was at the time the head of the religious books department at Harper & Brothers. Widely hailed as the dean of religion publishing in the United States, he had hundreds of bestselling books to his credit, including books by the popular Protestant preacher Harry Emerson Fosdick, the radical Catholic activist Dorothy Day, and the mystic and civil rights pioneer Howard Thurman.

As the letters flew back and forth between King and other editors, Exman took a different approach. He showed up in Montgomery, determined to convince King to write his first book. On October 17, 1957, at the age of 28, King signed a book contract with Exman.

The due date was less than three months away. King’s days were heavy with responsibilities, and he was besieged by death threats. Exman and King’s literary agent Marie Rodell agreed that the book would be written quicker and would read (and sell) better if King had help. Rodell floated two white ghostwriters as possibilities, but King insisted on writing it himself, with the help of his own hand-picked assistant: Lawrence Reddick, a Black professor of history at Alabama State College who would go on to become the author of the first King biography (also published by Exman).

A few weeks after King’s first book deadline had come and gone, Exman returned to Montgomery. In a letter from the newly discovered Exman archives, Exman told his close friend and coworker Margueritte Bro that King again refused outside help. “He said it would take two weeks for him to bring a ghostwriter up-to-date; also, he thought a ghostwriter might write the book as he wanted it and not as King wanted it,” Exman told Bro.

Later that month, King sent Exman draft pages from two chapters. On February 25, 1958, Exman convened an “editorial council” he had assembled to produce the book. The next day, Exman and Rodell wrote King independently. Rodell stressed that all involved were committed to producing a book that expressed King’s thinking “as clearly and faithfully and movingly, and on as broad a base of appeal to many people, as possible.” Exman similarly reassured King that his hand-picked freelance editor Hermine Popper “will not be working as a ghostwriter, but as an editorial associate.”

Popper, in her own letter, offered King additional reassurances, describing her work as an effort “to convert, as it were, an expert orator’s style into a writer’s style—so that your truly great story will speak for itself.” She told King that she had “added less than a dozen sentences” to the current pages, and none would be included without his approval.

The resulting book, King’s Stride Toward Freedom, was simultaneously uplifting and sobering. It documented not only how tens of thousands of ordinary citizens of Montgomery were willing to risk their lives to make justice but also how little integrationists were doing to support them. In his book and his life, King saw three kinds of American churches: Black churches working to relieve suffering, white segregationist churches continuing to inflict it, and white liberal churches sitting on their hands.

OBSERVERS HAVE LONG debated the intellectual formation of Martin Luther King Jr. In his books and essays, King credits Thoreau and Gandhi for his understanding of non-violent civil disobedience. He also pays his debts to Walter Rauschenbusch, Reinhold Niebuhr, and philosophers he studied with at Boston University.

Many have argued that this genealogy of King’s influences underplays the crucial influences exerted on King by his family, his church, and broader African American culture. According to the Black liberation theologian James Cone, the real King is to be found in the “preached word” of his unpublished sermons and the “practiced word” of his nonviolent direct actions. It is in those words that one hears unmistakable echoes of spirituals, the Black folk tradition, and the Black church tradition.

Cone and others are right to observe that King’s writings do not present some pure, pristine King. King would go on to write three books with Exman, and all were collaborations. However, his spoken words were collaborations, too. King had help with many of his speeches, as so many public leaders do, and drew extensively in his sermons from other preachers as well as white theologians and philosophers.

What emerges from this evidence is a picture of King as adept in cultural and religious combination, creatively mixing into a new theory and practice of nonviolent protest. Stride Toward Freedom was not a one-man show (few books are). But King was its producer. He rejected the white ghostwriters Rodell trotted out in New York City, bringing on Reddick as an advisor instead. He accepted Popper as his Stride Toward Freedom editor and chose to work with her on future Harper books because she did an excellent job setting down what King was thinking, doing, and feeling. Readers are right to find at least as much Alex Haley as Malcolm X in the “as told to” Autobiography of Malcolm X, which Haley completed after Malcolm X was himself assassinated, but King was alive and well when his first three Harper books appeared, and in their making he was neither passive nor disempowered.

THIS IS NOT TO SAY that Exman and his coworkers did not influence Stride Toward Freedom and the other two books King wrote for Exman (Strength to Love and Why We Can’t Wait). They did. In fact, they worked hard to bend their books on race in the direction of their desires.

Exman and his Harper colleagues saw themselves as allies in the civil rights struggle, but they wanted to improve “race relations” in the United States without posing any real threat to their own ways of living and thinking. Exman, to borrow from Ibram X. Kendi, was an assimilationist, not an anti-racist. In his religious book department, the desire for racial unity often produced a related desire to leap immediately to racial repair and reconciliation, as if centuries of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow could be overcome with one wave of a magic wand. Exman and other members of King’s editorial team were waving it when they asked King to end Stride Toward Freedom with “an eloquent plea for love and the brotherhood of man.”

Back when Rodell was trying to find a New York City ghostwriter for Stride Toward Freedom, King’s lawyer Stanley Levison had met alongside Rodell with two candidates. Rodell prepared for the meeting by going to the library and reading a couple articles by Reddick. Afterwards, Levison wrote to King about a disconnect he felt in the meeting:

This is the old story that too many white liberals consider themselves free of stereotypes, rarely recognizing that the roots of prejudice are deep and are tenaciously driven into the soil of their whole life. I know I did not resolve this for myself by reading a few articles and pronouncing myself a person of good will. The acid test I have always used is deeds involving significant sacrifice based on the acceptance of the painful truth that we share responsibility for the crimes and gain release from complicity only by fighting to end them. On this score the two men we met fell short.

Exman fell short, too.

His accomplishments at Harper were legion. He took a religious books department focused on selling books by Baptist pastors to Baptists and Episcopal rectors to Episcopalians and turned it into a powerful force for the popularization of the now popular idea that all religions are one. Guided by that pluralistic idea, he was a pioneer in bringing the writings of Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, and Catholics to American readers. Exman also integrated Harper’s religious books list, leading Coretta Scott King to praise him, in an inscription to Exman in her Harper-published autobiography, for his “contribution to the cause of justice, peace and brotherhood.” However, there is no evidence that he used his power as a Harper trustee to make Harper’s workplace more racially just. He served on the boards of nonprofits devoted to opposing war and eliminating nuclear weapons, and he devoted hundreds of hours to helping conscientious objectors get out of jail and find jobs. But he showed no similar urgency about undermining white supremacy.

Shortly after Stride Toward Freedom was published, the Harper’s Magazine editor John Fischer wrote Exman a memo about an article he wanted King to write. The article, Fischer wrote, would be “an epistle directed primarily to Negroes, reminding them that their present struggle for equality places certain special burdens and responsibilities on each of them.” Instead of calling on whites to acknowledge the rights of African Americans, the article Fischer envisioned would call on African Americans “to demonstrate to hostile, skeptical, and indifferent white people that they not only have a moral right to full civic equality, but are capable of handling it.” Ignorant of how distasteful it would be for King to receive a request to act as a ventriloquist dummy for a white man’s desire for peace without justice, Exman forwarded Fischer’s memo. In a cover letter, he urged King to write the article, which he described as a “step toward bringing Negroes and Whites closer together.” King did not comply.

Exman was not naïve about human nature. And he had firm faith. But he believed too much in the power of Providence when it came to the civil rights struggle. He was allergic to conflict, and often he did little more to resolve one than to wait for it to resolve itself. He justified this hands-off policy by telling himself (and others) that God was in charge.

After his New York City editorial team urged King to end Stride Toward Freedom with a paean to love and a plea for human brotherhood, King did just the opposite. He concluded the book with a prophetic warning worthy of the fieriest biblical prophets. They are words well worth hearing again today:

In a day when Sputniks and Explorers dash through outer space and guided ballistic missiles are carving highways of death through the stratosphere, nobody can win a war. Today the choice is no longer between violence and non-violence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence. The Negro may be God’s appeal to this age—an age drifting rapidly to its doom. The eternal appeal takes the form of a warning: “All who take the sword will perish by the sword.”

Stephen Prothero is C. Allyn and Elizabeth V. Russell Professor of Religion at Boston University and the author of the forthcoming God the Bestseller: How One Editor Transformed American Religion a Book at a Time.