Regulatory | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI

Proposal to Move Mexico’s CRE, CNH Into Sener Could Spook Energy Investors

Proposed legislation to move Mexico’s energy regulatory commission (CRE) and national hydrocarbons commission (CNH) into energy ministry Sener “directly contradicts” the constitution and “would go against every best practice in the book,” according to a Sener official.

The bill was introduced earlier this month in Mexico’s lower congressional chamber by Congressman Mario Delgado, a member of leftist President-Elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s Morena coalition.

“The Morena bill proposes to ”sectorize’ CNH and CRE, i.e. to have them become offshoots of a political office, albeit technical in nature,” the official, who requested anonymity, told NGI’s Mexico GPI. The official explained that the practice of sectorization has traditionally been applied to state-owned enterprises, not regulators.

The sectorization of CNH and CRE “is patently incompatible with a regulator’s mission,” the official said, explaining that it “undermines their mission to ensure competitive markets” and amounts to “preferential treatment for state enterprises.”

The state enterprises in question are national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and state electric utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), which held a duopoly over the energy sector until a 2013 constitutional energy reform that liberalized the industry.

The reform, which López Obrador has called a “total failure,” allowed private sector firms to enter the market, and imposed asymmetrical regulations on Pemex and CFE, both of whom previously held dominant positions throughout the entire hydrocarbon and electric power supply chains.

Although the boards of both Pemex and CFE are chaired by the energy minister, the Coordinated Regulatory Agencies Act of 2014 enshrines the independence and budgetary autonomy of CNH and CRE, and insulates them from political influence.

The act “is a fundamental piece of legislation in establishing investors’ long-term confidence in the Mexican energy markets,” the official said. “The commissioners’ overlapping, seven-year terms guarantee internal checks and balances against favoring particular interests and allows for each government to leave a gradual imprint on policy implementation.”

“Under the new structure, the Chinese wall [between regulators and the executive branch] would be breached, increasing the risk of political interference,” the official continued, adding, “This is major surgery and would likely scare away investors up and down the sector.”

Local industry players, officials and analysts also expressed concern over the bill.

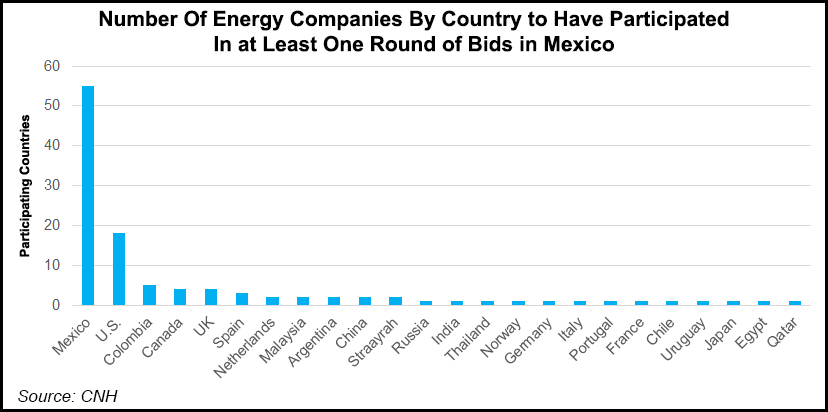

The Asociación Mexicana de Empresas de Hidrocarburos (AMEXHI), a trade group of private sector and state-owned oil companies with headquarters around the world and operations in Mexico, said Monday the proposed legislation “would negatively impact the autonomy of coordinated regulatory agencies in energy matters,” and that current law allows CNH and CRE to function as “independent referees” for the industry.

“These conditions were essential in the decisions of many of our members to make long-term investment commitments in our country, and also a guarantee of transparency to society,” AMEXHI added.

CNH commissioner Marcelino Madrigal wrote on Twitter that the news of the bill was “worrying,” and said “adequate division between functions of politics, business, and regulation is fundamental for a future energy sector that is secure, clean, and that benefits the consumer.”

Economist and director of the Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad (IMCO) Manuel Molano, said in a broadcast on Monday that the legislation represented a “step backward” and a clear attempt to undo a foundational element of the energy reform.

López Obrador’s top energy advisers, including future energy secretary RocÃo Nahle and the rumored future head of exploration and production for Pemex, Fluvio RuÃz Alarcón, have said that the new government will seek to modify the reform’s secondary legislation to give Pemex more autonomy, but that it does not plan to reverse the reform entirely.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |