It has all the makings of a classic murder mystery: A prominent small-town attorney comes home late one night to find his wife and 22-year-old son shot to death at the family hunting lodge.

The son was awaiting trial on three counts of boating under the influence stemming from a 2019 accident — charges that were brought only after the family of the dead woman filed a lawsuit implicating his family and questioning how law enforcement handled the boat wreck.

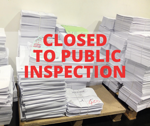

Local police are tight-lipped about the double homicide — refusing so much as to release the incident report that recounts the basic who, what, when and where of the crime — and they quickly turn the investigation over to the State Law Enforcement Division, saying they have a conflict of interest because the husband works in the solicitor’s office. SLED releases a single, tantalizing detail: The public, it says, is in no danger.

How can the police be so sure the public is not in danger? And why are they being so secretive about a double homicide involving a powerful family? The combination of those two questions feeds rumors and speculation that could be entirely off base, or that could taint a jury once an arrest is made.

The information blackout also violates state law.

South Carolina’s Freedom of Information Act, appropriately, allows police to keep the details of ongoing criminal investigations secret. They don’t have to tell us anything that could interfere with a suspect’s right to a fair trial, identify a confidential source or “interfere with a prospective law enforcement proceeding.”

But the law does require police to release "reports which disclose the nature, substance, and location of any crime or alleged crime reported as having been committed.” And more than a week after the June 7 killings of Maggie and Paul Murdaugh, the Colleton County Sheriff's Office and SLED each says the other one has the incident report, and no one has released it.

In fact, state law requires more than the normal disclosure procedure for 10 specific types of information, including those police reports. Rather than making people file a written Freedom of Information request and wait for the government agency to get around to providing it, the information must be available anytime the agency is open. Yet when The Post and Courier sent reporters to the sheriff’s office and to SLED headquarters, they were turned away.

Spokesman Tommy Crosby told the newspaper that SLED would not release any records because the necessary redactions would make them unreadable. Perhaps they would, but that’s not SLED’s call. State law demands that the information be released, immediately, adding that “Where a report contains information exempt as otherwise provided by law, the law enforcement agency may delete that information from the report.”

If that’s not clear enough, the S.C. Supreme Court spelled it out even more clearly in a 1992 landmark opinion involving SLED, explaining that police in our state have an obligation to provide whatever is left once they redact the information exempt from disclosure under state law. “If the legislature had wanted to create a blanket exemption for all criminal investigative reports, regardless of content, it clearly could have done so,” the unanimous court wrote. It went on to “emphasize that law enforcement agencies do not have carte blanche to deny all FOIA requests for criminal investigative reports.”

Newberry Publishing Co. v. Newberry County Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse is an old opinion, but it hasn’t been overturned, and the law hasn’t changed in any significant way. (Those four exemptions have since been expanded to seven, providing more detail but no new reasons that would justify withholding the incident report.) Neither has the basis for the law: The public needs to know what its government is doing, particularly about possible threats to the community.

SLED issued a statement Tuesday afternoon reiterating its position, and promising to release information "at the appropriate time." That time was more than a week ago. Somebody needs to redact any information in the incident report that is actually exempt under state law and release the report and 911 call; if we can’t make sense of it because it’s so heavily redacted, then so be it.

As the court suggested nearly 30 years ago, if police don’t like that, their remedy isn’t to ignore the law. It’s to convince the Legislature to change state law to allow them to hide basic criminal information from the public.