The container ship Hanjin Geneva is anchored 13 miles off the coast of Japan, near Tokyo, for the foreseeable future. The ship is carrying hundreds of containers, 25 sailors, and one unusual passenger—British performance artist Rebecca Moss.

She’s used to the absurd, but Moss wasn’t expecting to get caught up in a situation quite so bizarre when she set off on a 23-day journey across the Pacific Ocean, as part of an artists-in-residency program that stashes artists on cargo ships for a journey from Vancouver to Shanghai to spark their creativity.

“This predicament is oddly tailored to my interests,” said the 25-year-old artist, who produces videos placing herself in slapstick and absurd situations. In Animal Cruelty, she’s shown sitting patiently until a water balloon is dropped on her head by a cat that lets go of a blue string attached to the balloon.

In another she’s dressed as a frog, bouncing on a pogo stick in the countryside.

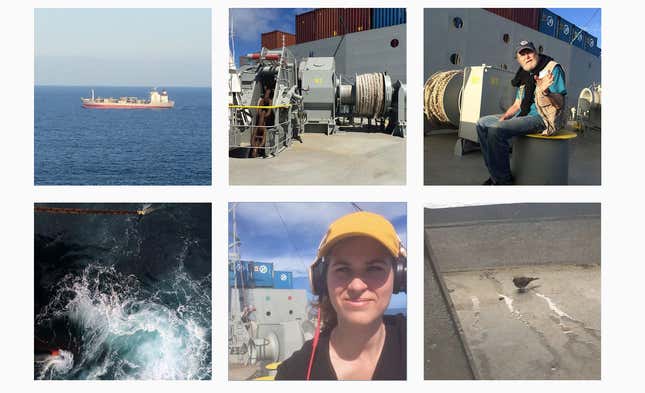

Onboard the Geneva, Moss’s Instagram account shows the cargo, the sea, a bird stowaway, and a man named “John” who another passenger. As of Monday, Sept. 12, she had been on the ship for 21 days, and it is unclear when she will get off.

While some of Moss’s work may a laughing matter, the state of Hanjin Shipping, the world’s seventh-largest shipping company, is not. The company filed for bankruptcy protection from the Korean courts on August 30, after a number of its creditors, including the government backed Korea Development Bank refused to provide a cash injection it needed to keep operations going.

The 39-year-old Korean company has amassed debt of $5.5 billion as it tried to ride out a six year rut in the industry that began after the 2008 financial crisis. It’s a rut that has forced some of Hanjin’s multi-billion dollar competitors into mergers, in a trade that moves some 90 per cent of goods around the world.

Because of its debt, Hanjin ships have been barred from entering ports and unloading their wares, leaving several thousand sailors stranded out at sea, said Kim Hye Kyung, a coordinator with the Federation of Korean Seafarer’s Unions. Some 3,000 sailors, mainly from Korea, the Philippines, and Indonesia, are affected by the collapse, with an estimated 2,500 at sea.

Hanjin Shipping was thrown a lifeline of $56 million on Sept. 10 by its sister company and largest shareholder Korean Airlines, and an additional $90 million was pledged by the Hanjin Group. But the company is still seeking millions in low-interest loans from the Korean government, a deal that as of today (Sept. 12) had yet to materialize.

There are concerns that food and water are dwindling on some of the 100 ships or so Hanjin has said are currently operational. On Moss’s ship, the captain has asked the crew to start conserving supplies, Moss said on Sept. 2.

“It seems that the government deal has problems, so we will have to increase our watch to make sure the crew members are cared for,” said Reverend Stephen Miller, the East Asia director for The Mission to Seafarers, an Anglican seafarer’s welfare organization. Miller said he was not as concerned as he was with the case of the New Imperial Star, a casino ship that was abandoned in the middle of Hong Kong harbor, leaving sailors stranded for more than 200 days.

There are two steps to the deal that need to be worked out between the company and the government—the short term financial problem of current debt, and a restructuring of the company. “Hanjin is a family owned company, the government is under a lot of pressure to make sure it doesn’t collapse, but it needs assurances that things will change,” said Miller.

Moss, meanwhile, is throwing herself into her art. “It has been eye-opening and challenging in every way conceivable, but I feel like the intensity with which I have been able to focus on my practice is invaluable,” she said.