Oct 21: NASA's metal mission, hungry hippos chew badly, music synchronizes us and more…

Cicada boom is trees' bane and risks and rewards of deep sea mining

On this episode of Quirks & Quarks with Bob McDonald:

A metal mission — NASA launches a spacecraft to Psyche

NASA has just launched the Psyche mission, beginning the spacecraft's journey to the asteroid belt to visit a kind of asteroid we've never had a close look at before. The asteroid, also called Psyche, is thought to be metal-rich, and could give insight into what's at the core of planets like ours. David Lawrence is a principal professional staff member in the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. He's also the lead investigator for one of the instruments aboard Psyche — a gamma ray and neutron spectrometer that will help determine the asteroid's composition.

Hungry Hippos don't chew very well

Hippos are known for their monstrous mouths and terrifying teeth. But as it turns out, those qualities haven't made them great chewers. A new study published in PLOS One shows hippos struggle with the side to side grinding movement that would allow them to chew their food efficiently. As professor Marcus Clauss and colleagues at the University of Zurich found, the herbivores seem to have sacrificed their chewing ability for qualities that would help in a different area: using their gigantic jaws to fight.

Music makes your heart go pitter-pat just like other people's hearts

The audience at a classical music concert experiences shared responses beyond simply the pleasure of listening to the music. Using wearable sensors and motion capture technology, psychologist Wolfgang Tschacher — a professor emeritus at the University of Bern in Switzerland — found that most people in the concert hall became completely in sync in terms of movement, heart rate and breathing rate. Our tendency to synchronize like this comes from deep in our evolutionary past. His research was published in Scientific Reports.

Cicadas boom and trees get busted

The emergence of cicadas every 17 years has a cascading effect on forest ecosystems. Zoe Getman-Pickering, a biologist who did her research at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., found that when the billions of cicadas emerge, they provide an instant and abundant food source for many animals, including the 80 bird species that were studied in the eastern United States. This means caterpillars thrive as birds ignore them, resulting in more leaf damage on their host oak trees. Her research was published in Science.

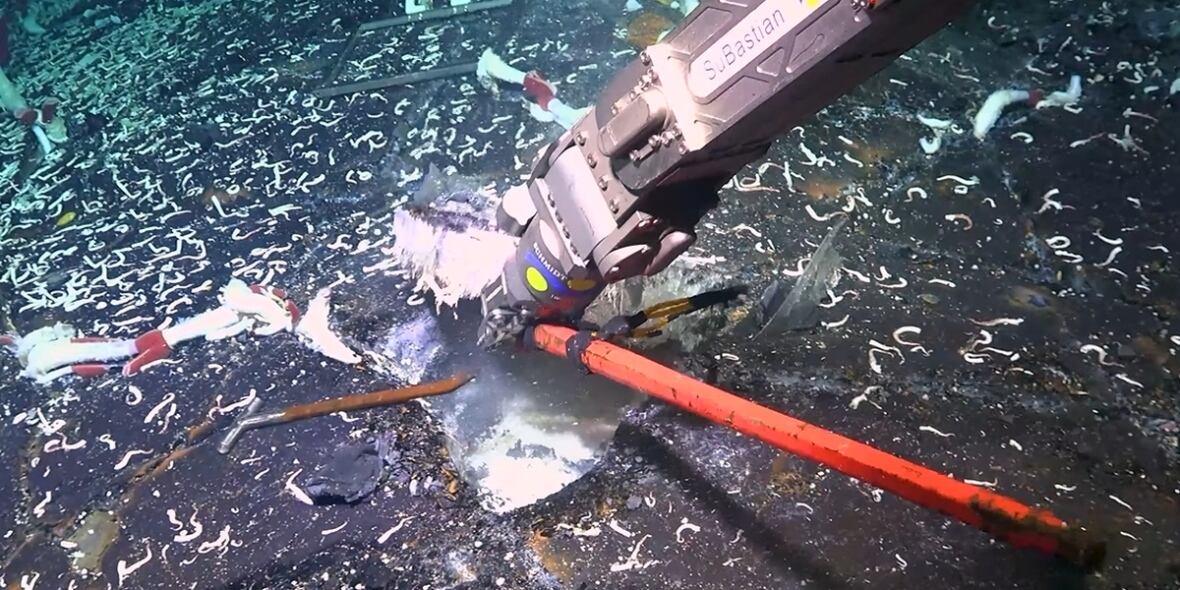

Understanding the risks and rewards of deep sea mining

Commercial interest in mining valuable metals from the deep ocean floor has increased enormously in recent years, but we've also begun to realise that these ecosystems are home to rare and fragile forms of life. A recent expedition to mineral-rich hydrothermal vents in the Pacific Ocean discovered subterranean habitats under the vents that are teeming with life. Sabine Gollner, from the Royal Netherlands Institute of Sea Research, said these underground cave habitats may be connected, and therefore we need to learn more about them before they're mined.

In another very different type of environment, balls metal called of polymetallic nodules, full of valuable minerals lie scattered on the seafloor. Muriel Rabone, from the Natural History Museum in London, said she and her colleagues estimated there could be as many as 6,000 to 8,000 species living on and near these nodules, 90 per cent of which are unknown to science. Their study was published in the journal Current Biology