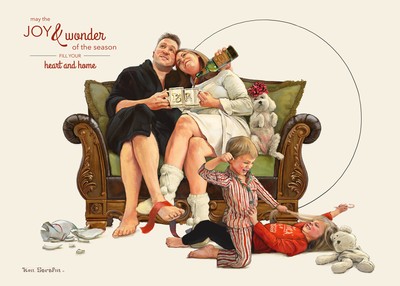

Six years ago, Ken Sarafin created his inaugural family Christmas card. Harnessing the aesthetic of Norman Rockwell—the 20th-century painter known for conveying the everyday life of Middle America—Sarafin illustrated a portrait of his sister, her husband, and their then-newborn daughter. The painting showed Sarafin’s niece crying on the floor, with her father nearby wearing a disheveled tie and drinking a martini, and her mother talking on the phone while mixing something in a bowl; in the background sat a small, scraggly, Charlie Brown–esque Christmas tree. “We were kind of going for 1950s Americana and its traditional gender roles on that one,” Sarafin recently told me.

At the time, Sarafin—a 33-year-old graphic designer in Denver who doesn’t have children of his own—saw the card as a perfect opportunity to put his painting hobby, and his newfound affinity for Rockwell’s style, to use. It was also a way to bond with his family—and to poke fun at the classic family holiday card, with its matching sweaters, forced smiles, and feigned peace. Sarafin and his sister had never been fans of “Christmas cards that are overly cheesy and cutesy and look how great our family is,” he says. He’s illustrated a similar portrait of his sister’s family in disarray every Christmas since.

Americans today are sending far less snail mail than they used to: The overall volume of physical mail in the United States has dropped 43 percent since 2001, according to the U.S. Postal Service. But one form of conventional mail that has somewhat bucked this trend is greeting cards—especially family holiday cards. While the rates of sending cards have declined slightly, today’s Americans buy 6.5 billion greeting cards annually, according to data from the Greeting Card Association. Of those, 1.6 billion are for Christmas, the largest card-sending holiday in the country. And greeting-card mail, it seems, has declined at a much lower rate than overall mail.

Industry data suggest that interest in family holiday cards is on the rise. For example, Google data procured by Shutterfly, a nearly 20-year-old online company whose products include customized photo cards, show a steady increase in the number of queries for family Christmas cards. Etsy, the online marketplace where artists can sell handmade products, has seen a similar uptick: From September to November of this year, the number of searches on the site for custom cards, like those featuring personalized family portraits, was 258 percent higher than it was last year during the same time range, a company executive told me.

These data, experts agree, hint that Millennials are a key component of holiday cards’ staying power. Millennials are the target demographic for sites such as Etsy, as well as newer custom-card companies such as Minted. And while people of all ages participate in the tradition, people tend to start sending holiday cards when they hit a milestone such as marriage or a first child—and Millennials are the generation currently hitting those landmark events. Although the USPS report found that the decline in snail mail is especially pronounced among these Millennials, it also identified this generation as the demographic that could save the post. Amanda Stafford, a co-author of the report, suggests that the Postal Service ought to leverage young Americans in part because the lower volume of the mail they receive makes each piece of correspondence more special. Stafford says this age group may be especially drawn to the personal touch—the handwriting, the tangible photos, the labor of addressing and placing postage on an envelope—that only conventional mail can provide.

According to data from Hallmark, Millennials represent nearly 20 percent of the dollars spent on greeting cards, and their spending is growing faster than that of any other generation. And according to focus groups convened by the company, 72 percent of Millennials enjoy giving cards, while 82 percent enjoy receiving them; a similar number of young adults today typically save the cards they receive, too. Consumer research conducted by other card companies echoed these results. “People use so much less paper these days that when they do use paper, they want it to be really nice and special,” says Mariam Naficy, the founder of Minted, an online marketplace that crowdsources designs for photo cards. The rarity of snail mail, Naficy suggests, makes personal correspondence such as family holiday cards more meaningful. One young adult I spoke with—Alison Cuevas, whose card this year features an image of her and her two rescue pets against a galactic backdrop—described such correspondence as a “novelty.”

Social-media fatigue was a common theme across my conversations—it’s just nice sometimes to get a message from a far-flung loved one that doesn’t entail looking at a phone. “You’re more connected than ever, but in the same way, it’s all transitory connection,” says Mickey Mericle, Shutterfly’s chief marketing executive. “People feel this ephemeral connection, and they want to make it meaningful and lasting at certain points of the year … Holidays are a perfect time for that.”

Young adults such as Sarafin highlighted the value of the tactile experience of cards, of the way they allow a degree of personalization that can’t be replicated on social media. “Anything you post on a digital platform gets buried by all the other digital things around it,” says Yuliya Goloida, a 23-year-old graduate student in Toronto whose card this year features a picture of her, her boyfriend, and her black cat Tusya. A family holiday card, on the other hand, is a “tangible memory that is protected from the bombardment of other images—it brings back the privacy and personal aspect” of photos, Goloida told me.

It’s no wonder, then, that consumer researchers have noticed customers gravitating toward old-fashioned aesthetics—echoing the surging popularity, more generally, of gifts such as wooden toys, for example, and items made to look like cassette tapes. Of particular appeal these days are customized cards featuring plaid or white borders evocative of Polaroids, according to Minted’s Naficy.

But while some are keeping it traditional, others are embracing sillier aspects of the holiday card. As Naficy puts it, there’s been “a movement away from formality toward informality.” Christmas cards became popular in 20th-century America in part because they served as a means of signaling a family’s prestige—hence the (bygone) trend of sterile, overly stylized portraits of the clan in front of, say, the fireplace, or of a generic backdrop courtesy of Sears. But times have changed, and these days family holiday cards will typically feature just one such photo, if any, Shutterfly’s Mericle told me. “The rest are silly—they’re everyday moments, they’re spontaneous,” she says.

While children are still the most common characters on holiday cards—data from Minted suggest that kids appear in three-fourths of today’s family holiday cards, for example—the definition of family has steadily expanded. Goloida says that when she was growing up, she dreamed of partaking in the tradition by having a family of her own pose and dress up for photos. But in her early 20s, she didn’t want to wait anymore and decided that she, too, could send out Christmas cards—even if she didn’t have a husband and kids. (Last year’s Goloida-family Christmas card, the first of what she expects to be a lasting tradition, featured a photo of her and her now-deceased three pet rats.) Card-company representatives confirmed that a growing percentage of cards feature pets.

Regardless, Christmas cards provide couples and families with a way to express their originality and remind their loved ones that they care with a fun, unique greeting. The irony is that this form of correspondence traces back to the mid-1800s, when a British civil servant—eager to clear a backlog of mail to which he felt obligated to respond in accordance with Victorian social norms—invented the idea as a crafty means of mass-distributing personalized correspondence.

Part of that original motivation lives on: Research has found that consumers want the creation of the cards to be as convenient as possible. So corporations such as Shutterfly and Hallmark are striving to make their services as seamless as possible—using AI to create photo collages, for example, or suggest ideas for customization so buyers don’t have to deal with the labor of sorting through their massive photo libraries.

Ryan and Mallory Wales, a couple in Indiana, made their inaugural holiday card this year, a few months after having their first children, twins. Ryan, 31, took the photo, deciding to go with dim Christmas-themed lighting because of the soft look; Mallory, also 31, used a smartphone to design the card, which featured the twins. But it wasn’t effortless, they stressed. “Even in our busy lives, we took the time out to do this—to actually put them together and mail them out,” says Mallory. “It’s just different from taking that picture and putting it on social media for the likes.”

The convenience of the digital age married with the personal touch of snail mail may help the tradition last. “A Christmas card is just to show people that we know that we still have contact,” Ryan Wales says. “It’s always more personal than anything Facebook, Instagram, or even an email or text can deliver. And that’s the way I look at it: It’s kind of like we’re mirroring this old and new world.”