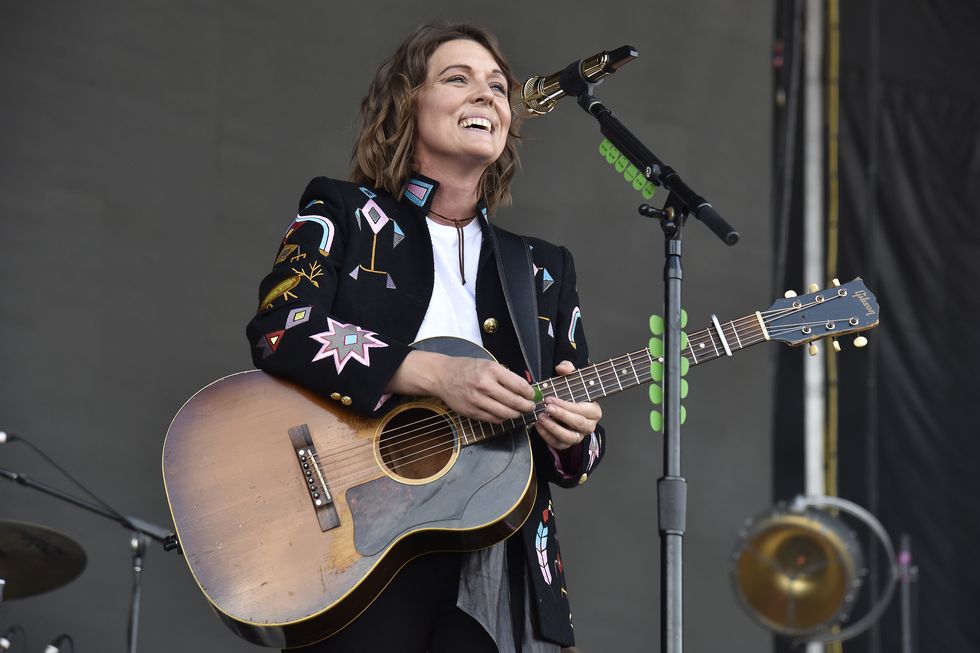

Katie Pruitt, a 27-year-old Americana artist who recently released a defiant album about being a lesbian raised Catholic in Atlanta, is about to enter into her Saturn returns era, which means her life is going to get weird. Or so Brandi Carlile, the six-time Grammy winner whose name has become synonymous with Americana over the last decade, and who just released a remarkably honest memoir that delves into her life as a queer musician, tells her. "You're going to freak out, probably," Carlile says. "Right when you turn 30." But, Carlile assures her, "I feel like the best records happened on these big, precipice moments in life."

Carlile was right around Pruitt's age now when she released her own Saturn returns record, The Story in 2007, which launched her into her "euphoric" thirties and what she hopes will be her even better forties. "Maybe it's just for queer people, but the times get better as we get older," Carlile tells Pruitt over a Zoom call in late May. And despite coming off that monster of a debut album, Expectations, which nabbed her a nomination for Emerging Act of the Year from the Americana Music Association, Pruitt doesn't pass up the encouragement. "Fuck, yeah. Thank you, Brandi. I needed that confidence boost today."

Pruitt and Carlile first met at a benefit concert for victims of the Nashville tornado, right before the pandemic set in—in that surreal span of time when people weren't sure they should be hugging each other, but pre-lockdown, they both recall. It was the last time they saw John Prine, and it was the last time for a very long while that either would play live on stage. A year and change later, with the promise of live music imminent, Esquire asked them both to join a conversation over Zoom (Carlile from her home in Seattle, Pruitt from her place in Nashville) about their careers as two queer Americana musicians, as well as the tension between country and Americana music, giving a platform to people of color and LGBTQ people in their industry, and singing with so much emotion it just about breaks your heart to listen. Here's that conversation, slightly edited and condensed; they had quite a lot to say.

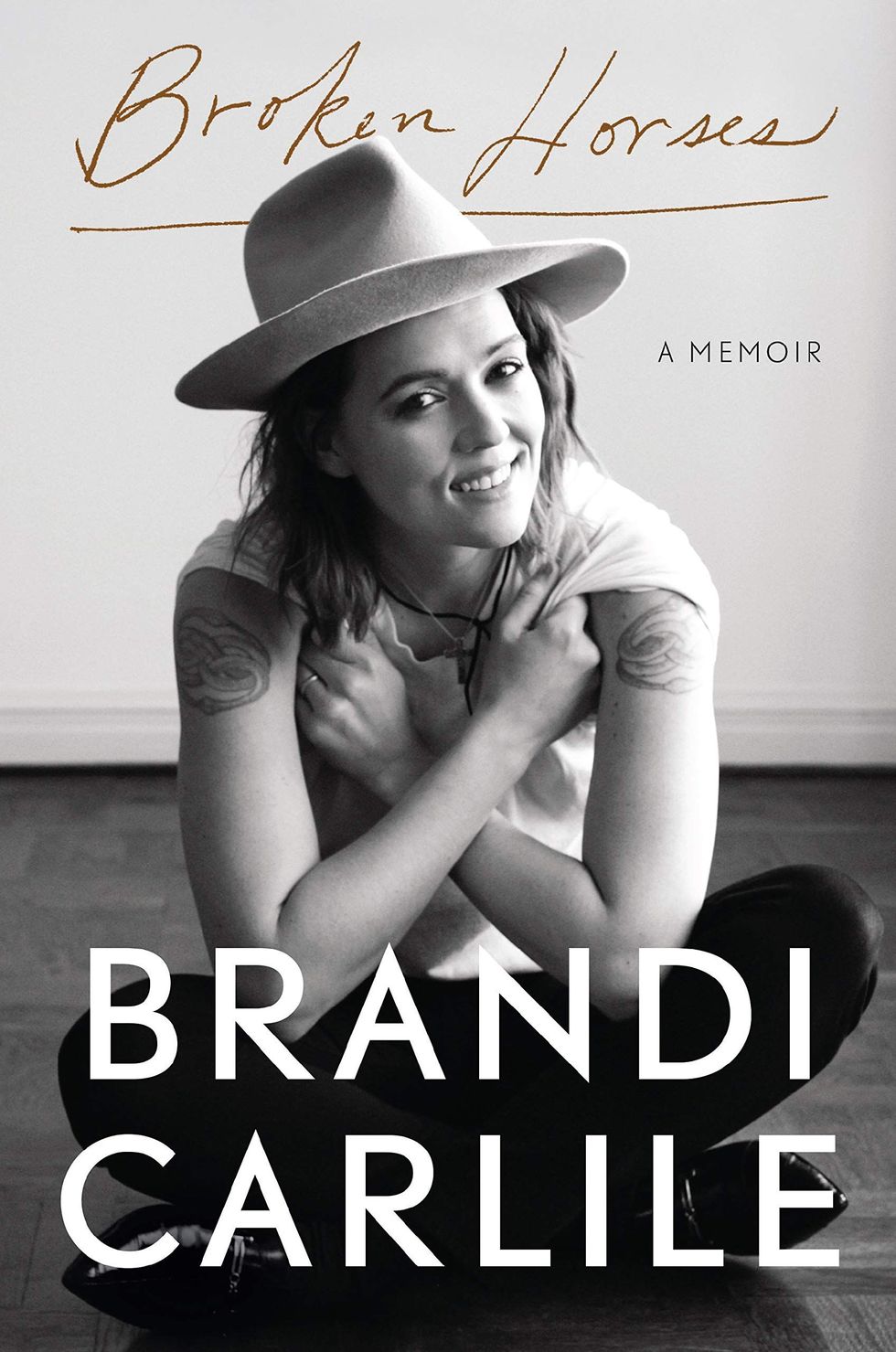

Katie Pruitt: My mom bought me your book, Brandi. So cute. She's a huge fan of you.

Brandi Carlile: I'm glad somebody's mom likes it.

Esquire: In your book, Brandi, you talk about these Americana elders that you revere, like Bonnie Raitt and Dolly Parton and Tanya Tucker. Now you're inspiring a new generation of Americana writers. What does that feel like?

BC: All I can say is, I get it. I really get it. I'm not one of those folks that's going to be like, "Oh, I don't inspire a generation of anything." But I do get it, because I had it. I'm grateful for the people that inspired me and really just wanting to at least have a look at filling those shoes, even if it's not entirely possible.

ESQ: Katie, who's inspiring you to write?

KP: Brandi is definitely one of them. I've wanted to ask you this for a while, Brandi. When I was coming up, there weren't really those societal struggles of me being an out LGBT songwriter, but there were obviously struggles in my personal life, which I guess still made it difficult. You as a 27-year-old, what obstacles did you face, being a queer woman in Americana music? 'Cause without you, I don't think I could have been as just, I don't know, not-subtle on Expectations.

BC: I love how not-subtle you are.

KP: I just lay it all out there, but that definitely would not have been possible without you. So I wonder what it was like when you were my age.

BC: Well, I think that you still have obstacles, and sometimes it's even worse when you're not expecting them—when you think the world's gotten to a place where it maybe hasn't gotten to yet, and you're taken by surprise that these archaic systems and oppressions are still in place. Maybe they're a little more subtle, but it's like, I'll take a wolf in wolf's clothing over a wolf in sheep's clothing any day.

So I still really respect immensely what you're doing and how frank and out-there you are about it. It's still brave, it's still revolutionary, and it's still helping me, even though we're not the same age and we're not in the same place physically or career-wise just yet. I feel you're still paving the way backwards, because I don't think progress only moves in one direction. You have to be constantly on guard. Like for instance, when I was growing up in country music, I had all of these icons, all of these amazing female artists that were getting platformed and played on every radio station—absolutely zero women of color, but plenty of women at least. And then cut to 2016 and there's like two or three. That's like, oh my God, progress went backwards. But it can do that, in LGBTQ rights too. That's why you have to just keep paving. I had obstacles, but a lot of times I only see obstacles in retrospect, because I'm so insane, and driven. What are some obstacles that you have felt coming up?

KP: Opening tours as an outwardly gay songwriter for a bunch of men. Like pretty much in 2019 and 2018, I was only put on bills with men. So it was like, okay, here's your diverse, different opener. And sometimes crowds would be a little...

BC: It's always in the opening gigs. You're like, "Ooh, I sense some unfriendliness and I don't know what to do."

KP: It was either like, "Oh my gosh, I love what you're talking about, I think it's really brave." Or it was like older people: "I don't know what to say to this lesbian songwriter right now talking about her experience, I'm uncomfortable." Really that's the only obstacle, and it's not even an obstacle.

BC: No, they might not know how to react in realtime when you do that, but then they go home and they think about it. And then what you've done is unwittingly made it easier for their niece to come out to them. You know?

KP: I actually didn't think about it that way.

BC: It's like you take the discomfort upfront and then they go home, and their niece comes to them a month later and says, "Hey, uncle so-and-so who just came back from MerleFest, I'm gay." And he goes, "So you know that Katie Pruitt girl?" It's important in ways you'll never get thanked for and that nobody will ever see. But, I see it. I just want to point it out to you that it's great, what you're doing.

KP: That's awesome to hear from you, for real. Other than that, there weren't any industry obstacles, and I truly think that is because there was a Brandi Carlile and there were Indigo Girls. There were queer artists that have had success, and I hope the same happens for people of color and in Americana. That these labels, these industry folks, start seeing, "Oh, this appeals, this makes money." Which is dumb, but that's the way they think. People like you and people like Allison Russell and Amythyst Kiah and Brittany Howard, I mean, labels are like, "Oh my gosh, yes."

BC: It's moving the needle for sure.

KP: Totally, for another Black artist or queer artist to come up behind them.

BC: Or God forbid, both.

KP: [laughs] God forbid both, yeah.

BC: The thing I like about us queers is I find that our first instinct isn't to be competitive with each other. It's just each other getting in the door and thinking, "This is good for me, this is good for my family, this is good work. How can I get that door open a little further for her or him or they or them?" I come up from this environment of this kind of slumber party mentality—and I remember that because I remember slumber parties being quite traumatic for me—and how like, I have a job right now where people that think like me and people that have a life like mine, that look like me in one way or another, are supporting each other. I'm not trying to be Pollyanna about that shit, but it's pretty cool.

KP: No, it's super cool. There's this collective struggle that we've all shared of feeling unincluded, whether that be in childhood or anywhere along the way, if you were queer and especially if you're Black. So I think it's, "I'm here for you.” It's just this automatic bond.

BC: Do you have a genre of music that you identify with—you'd call yourself I'm this artist or that artist?

KP: I'm trying not to do that. It's like, some days I'm on a Jason Isbell kick and then other days I'm on a Jeff Tweedy kick and then other days I'm on a Radiohead kick. I listen to so much different music that I don't want to box myself in musically. I feel like the sky's the limit on how you want to sound and explore sonically. I try not to be like, "I'm Americana." But I think this record [Expectations] was Americana, and I definitely have been embraced by that community, and I think it's rad.

BC: It is rad. T Bone Burnett used to tell me when we were making our record, The Story—he's such an encyclopedia of roots music—he thinks it should all be called rock and roll. Everything should be called rock and roll.

KP: I kind of agree.

BC: I mean, I don't know. Sure. I'm quite comfortable with the phrase Americana these days.

KP: I like it because of what you said, the company is so good.

BC: I don't even know if it's a musicality anymore. I just think it's American roots and rock and roll music with a mind towards progressive thinking and inclusion. It's like an answer to its opposite in a certain way. You can find in Americana music everything you just said, except for Radiohead. Anything from Tom Petty to Lucinda Williams to the Alabama Shakes to Pearl Jam all feel Americana to me, at least in the psyche and in the way of life that sort of encompasses American roots music with an eye for inclusion and platforming underserved people. It's like misfit toys.

KP: I love what you said, that it's an answer to its opposite, meaning Americana music is kind of that Nina Simone quote of: Art should reflect the times. Even if they're uncomfortable conversations for some people, being brave enough to put that in a song does move the needle.

ESQ: Brandi, you mentioned this in your book and it made a buzz at the 2018 Americana Music Awards, when Tyler Childers said that he made “country music”—he diminished the value, I guess, of "Americana music." I think from a fan point of view, some people expect Americana artists to be gunning for country music, that pop radio, top-10 chart. I wonder if it matters to you at all, and how you compare these two genres?

BC: One of them, I think, might be a closed door to me. And when it appears that it's open, I'm suspicious of it. I think it could be a little tokenizing at times, especially where the corporate side of that genre is concerned. And I don't have a mind towards it, because I find everything that I need in the place where I can effect the most important change. I don't know Tyler, but I'll be really honest with you, I have a shitload of respect for him, especially after his speech on Long Violent History and the work that he's done to get sober. If that's the person I think he is, I don't think he would give that same speech now, understanding who was there, who was being honored, and why it was important to us. I don't think he would stand up in front of all those people and say, "I don't want to belong to you. I want to belong to this." Because I don't think it reflects where his mind is at or has come to. And actually, I can see what he's saying: He's protective of the original concept of country music, and he needs it to not mean something politically isolating, but sometimes it just does.

These genres have been in flux and splinter, they've been like churches. That's why we have names like American roots and hellbilly and bluegrass and folk and Americana and country and country Western, traditional country, modern country, pop country. I'm not trying to add fuel to the fire of that fight. I'm just acknowledging that there's a place where I feel that I can work within. I can feel accepted in a community of people that are actively platforming people of color—not tokenizing, but platforming people of color—and platforming queer people, and also actively addressing things like class division and progressive mindedness. That just interests me so much that I can't really get distracted by the other concept.

I think that if me and Tyler Childers sat down and had a coffee—not a beer—that we would probably come to pretty much the exact same conclusion, with a deep and innate love and appreciation for country music and what it's done for us in our lives. It's a long answer, but that's the way I feel.

ESQ: Do you ever think about outreach to fans of country music who might not realize that Americana has become this community of artists who are doing this protest music, doing this inclusive platforming, like you said? Do you think people are aware of it?

BC: I hadn't thought about it, because I think people will find their way to the music that tells the story of their life. You think about mainstream country and there are some great stories in there right now. I mean, my girl Maren [Morris] telling the story of the other half of the human race all the time, every single day, and just owning that genre. All I can do is just raise a roof on that girl and say, “Keep doing it, 'cause we need you there.” Mickey Guyton with “Black Like Me?” These stories are getting out to ears who need to hear them.

KP: Good songs are good songs, just with different sonic backdrops and a different genre slapped on there.

ESQ: As some of the very few queer women writing Americana music right now and just being seemingly fearless with pronouns and the way you talk about love and coming out, do you ever feel any pressure?

KP: No. I think it's our responsibility to write about what we see and what we feel and what's happening in our lives. The queer experience is going to make its way in there, because we are queer. But also, that isn't our entire identity. I don't want to feel the pressure to talk about the queer experience in every song or all the time. I think Brandi walks this line really well. She talks about human experiences and she happens to be queer. That is important for people to see, like, "Oh, this is a love song." It happens to be a love song to a woman, but a straight man can listen to that and think of his wife.

BC: I used to write songs intentionally vague. I wanted people to be able to experience through their own lens. But say even a song like “The Mother," I very specifically say, "I am the mother of Evangeline," which is a rare name. It's too specific to universally be a cloak that anyone can put on, yet it's probably the most related-to song I've ever written by fathers and mothers, gay, straight, trans, also kids feeling affection towards their parents, people with sons instead of daughters. When it sounds like the truth, they feel it. I'm seeing that more and more straight people are identifying with gay relationships, which is like, "Oh my God, that's actually what we always... "

KP: 'Cause they're just relationships. It just happens to look a little different.

BC: They come with a whole bunch of hysterical stereotypes, but yeah.

KP: I just bought a Subaru. I'm super stoked about it.

BC: You went there.

KP: I really did. And we have a pit bull. We've got all the gay things. The first time I heard you sing “The Mother,” Brandi, it was at the Basement East [in Nashville]. I cried so hard. I'm not even planning on being a mother or thinking about that part of my life really yet. It's such a relatable song, because it's this human truth.

BC: Thanks, buddy.

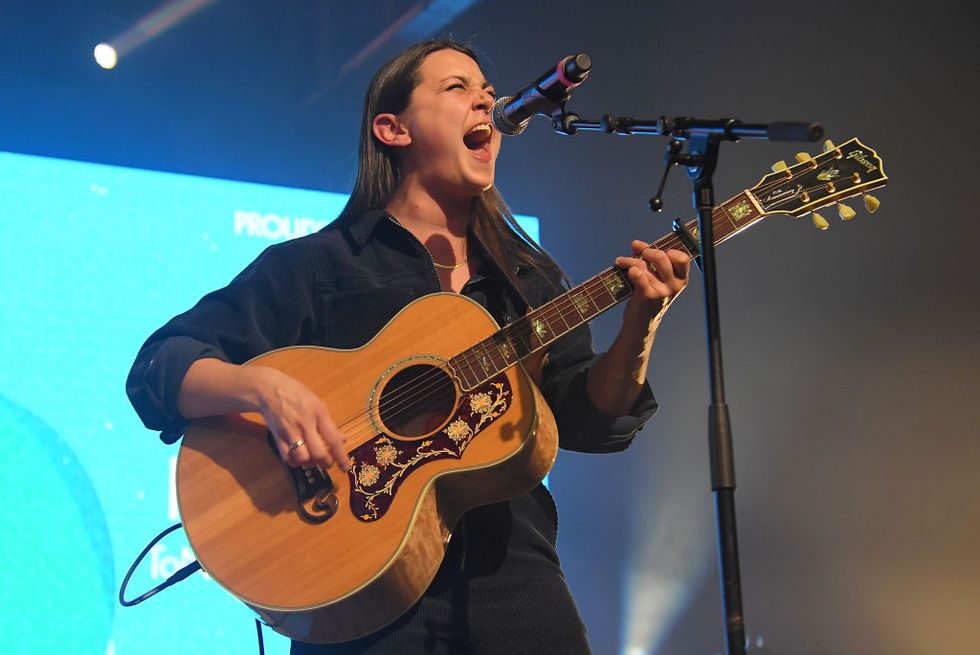

ESQ: I came into Americana music mostly through male artists—my dad listened to a lot of male artists, so therefore I did—and then you two come along and the way that you sing, actually hearing your voices, they break and they soar and they wail sometimes, it's just so much emotion. It feels like female emotion. Does it feel as emotional to sing like that as it is to listen to that?

BC: Nobody really mentions that that's also an Americana identifier—really odd and brave and strange singers. Like Emmylou Harris, super strange and character-filled voice. Lucinda Williams, one of the most character-filled voices in Americana history. That had an enormous influence on me, and it feels amazing to sing like that.

In the pandemic, I sang less than I've sung since I was 8 years old, and it actually caused me mental health problems and physical health problems, not having that outlet, that screaming, soaring, breaking, emotional wail that I get to do for a job on a regular basis. My wife always tells me—we'll get in an argument and she'll be like, "You have an outlet, darling." And it's like, after the pandemic, she's fucking right. She's exactly right. I do. And I did. And I'm going to again. But yeah, to sing like that, it's a decision. It's a skill, but it's also a lack of one. And it's very decidedly Americana.

KP: I miss belting on stage so much. It's like this spiritual release, and it's the best gift ever. I used to be in musical theater... that was the first time I got inspired to belt. Then there is definitely that in Americana, especially Brandi. Hearing some of the notes she hits and goes for live and on her record definitely made me go, "Okay, I'm going to do that on mine."

ESQ: I just have one more question. Of each others' songs, do you have a favorite? One you’d want to cover, maybe?

KP: Well, “Turpentine” is awesome. I love that one, but god, “The Story.” “The Story,” dude. I'm thinking of a specific moment though, at the end of the recording where your voice breaks...

BC: It's like a squeak. And you know, that's a Sheryl Crow thing. It's a song called “Crash and Burn,” and she does this squeak. It happened on accident on “The Story.” Katie, I was blown away by “Loving Her” and “Grace.”

KP: ["Grace Has a Gun"] is kind of a traumatic one, but yeah.

BC: Is it a true story?

KP: It sounds more intense than it was. It is just about a toxic relationship with my first girlfriend, and yeah, just some mental health issues. Codependency. There might've been a gun, but that's all I'm going to say.

BC: Brilliant song.

Get unlimited access to Esquire's Pride 2021 coverage. Join Esquire Select