Hocus Pocus

The magical resilience and enduring utility of Big Bend’s prickly plant life

By Matt Joyce

Photographs by Sean Fitzgerald

Illustrations by Marieke Nelissen

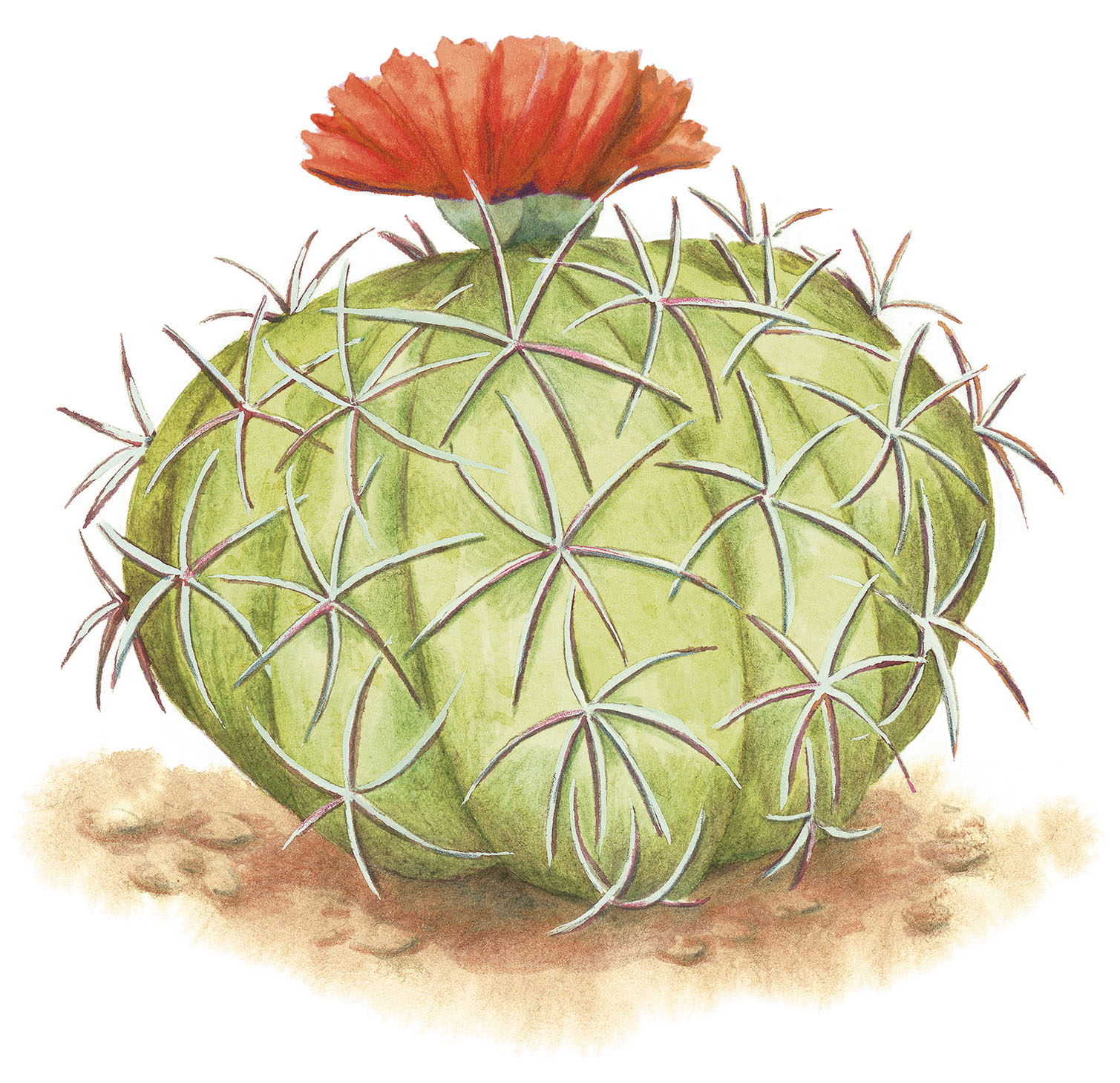

A close-up look at an obregonia cactus at the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center; an illustration of an eagle claw cactus

When people envision the Big Bend region of West Texas, they often think of the expansive views—desert basins, rocky canyons, and stark mountains on the horizon. But when stepping into those dreamy vistas in real life, it’s advisable to watch your feet. Otherwise, you might get poked.

Cacti, agaves, and yuccas armed with every manner of spine, claw, and thorn carpet much of the Chihuahuan Desert. These hardy plants thrive in a rocky landscape of arid soils that gets an average of only about 12 inches of rain per year. Once a person makes peace with their prickly threat, these spiky plants may actually outshine the views, especially when cacti blossoms explode in bright colors in the spring or after rainstorms.

“Cacti are absolutely amazing,” says Michael Eason, a botanist who wrote the 2018 guidebook Wildflowers of Texas. “They’re so adaptable, and then there’s their morphology. They’re very charismatic plants.”

Texas is home to 136 different kinds of cacti, and about 80% of those are found in the Trans-Pecos region, which encompasses Texas west of the Pecos River. This diversity makes the Trans-Pecos one of the richest cactus habitats in the country.

A. Michael Powell, professor emeritus of biology at Sul Ross State University, attributes the diversity to the varied topography. “Look at the mountains, the exposed soil types, the desert—there are many different habitats here,” says Powell, co-author of the 2004 landmark volume Cacti of the Trans-Pecos & Adjacent Areas. “Look at the Marathon Basin, for example. There are probably seven rare species of cacti in that little region alone. There are situations like that all over the Trans-Pecos.”

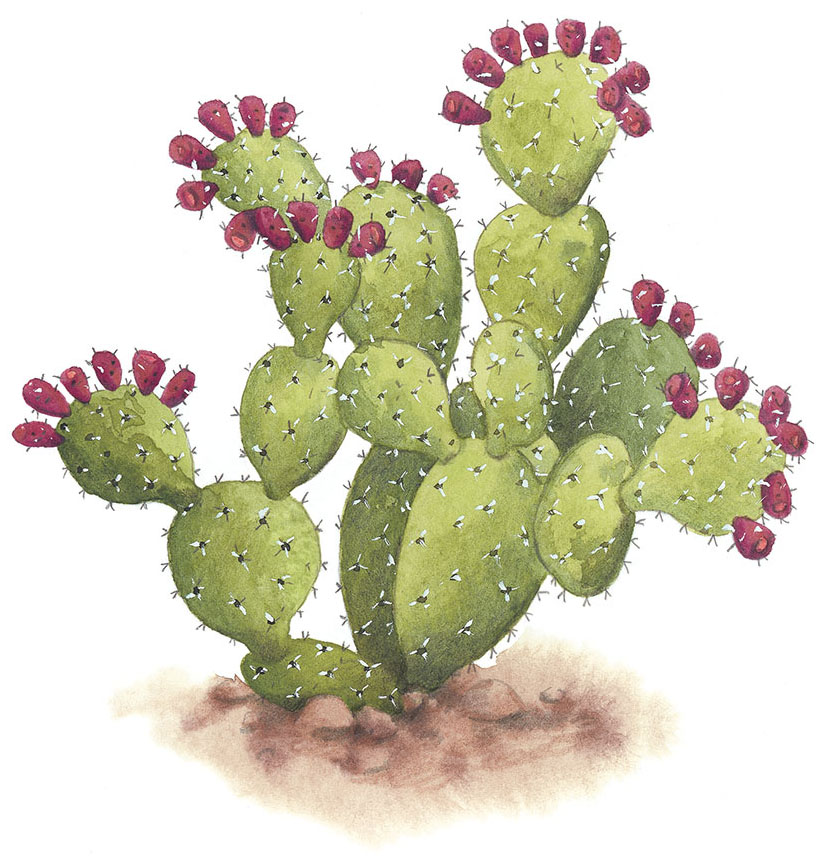

While often lumped together, cactus, agave, and yucca come from different families—the cactus family for cactus; and the century plant family for agave and yucca. Botanists distinguish the families based on flower shape and other characteristics. All have adapted to thrive in the desert in countless ways. Many have shallow roots that fan out, positioned to capture precipitation. Some, such as the prickly pear cactus, are succulents with thick pads that retain moisture. The spines of cacti—perhaps their most infamous attribute—provide protection from predators, and also offer camouflage and shade. Other plants, like the agave lechuguilla, have leaves that are shaped to catch moisture and funnel it to the protected base.

These plants play a central role in the desert ecosystem. Wildlife depends on them. Bees, butterflies, birds, and bats feed on the nectar of cactus and agave flowers; black bears chomp on prickly pear tunas; and javelina tear off lechuguilla leaves for sustenance. Humans have also relied on desert plants throughout history, harvesting them for food, fiber, building materials, and, in the case of peyote, hallucinogenic religious experiences.

The same qualities that make these plants so fascinating also make them popular with gardeners and collectors. While many Chihuahuan Desert plants are available from nurseries that grow them from seed, for decades collectors and dealers have uprooted them from the wilderness, sometimes illegally.

The problem has intensified with the advent of online marketplaces such as Facebook and eBay, says Eason, who splits his time between Alpine and San Antonio, where he’s the head of rare plant conservation at the San Antonio Botanical Garden. Scrolling through listings for Ariocarpus—commonly known as living-rock cactus—Eason can identify plants that have been poached from the wild by their scars and old age. Young and unblemished plants are more likely from greenhouses.

Collectors across the U.S., Europe, and Asia covet desert cacti, and many of them place a premium on rarity. One person may not think they’re doing harm by taking home a cactus from the desert floor, Eason says, but the reality is that hundreds of thousands of plants have been poached from the wilds of Texas, the Southwest, and northern Mexico.

“One of the biggest things I’ve seen in my career is the loss of populations,” Eason says. “We’re losing diversity every day. We should be conserving as much biodiversity as we possibly can and realize that these plants are important just because they exist.”

Here we celebrate these desert icons and their existence in the Big Bend region of West Texas.

Five Cactus Hikes in Big Bend National Park

The Dugout Wells nature trail in Big Bend National Park is only a half-mile loop. But when walking the path with a cactus fan like Cathy Hoyt, the barren landscape proves to be much more than meets the eye.

“Here in the Chihuahuan Desert you have to get out on foot because the beauty of this desert is in the details,” says Hoyt, a Big Bend interpretative ranger. “We have little cactus that are just treasures, and you have to get out there and look for them.”

Hoyt recommends the following trails for a closer look at Big Bend’s cactus, yucca, and agave populations.

Dugout Wells: On this half-mile trail, see three types of prickly pear, strawberry pitaya cactus, Christmas cholla, giant fishhook cactus, big needle pin cushion cactus, nipple cactus, and others. Beneath mesquite trees and creosote shrubs, bunches of cacti have taken root under the protection of “nurse plants” that shield them from the elements and predators. Signs along the trail explain how plants have adapted to the arid conditions.

Panther Junction Visitor Center: Located near the center of the park, Panther Path explores a rocky garden with placards identifying more than 30 desert plants. The stubby tubes of the rainbow cactus, long spines of the strawberry pitaya cactus, and protective orb of needles on the nipple cactus illustrate the diversity of shapes and sizes.

Dagger Flat Road: Four yucca species live in Big Bend—Faxon yucca (also known as giant dagger), beaked yucca, soaptree yucca, and Torrey yucca (also known as Spanish dagger). All of them grow along this 7-mile road across the desert floor (high-clearance vehicle required). Spring is typically the best season to see the yuccas’ voluptuous white flower bouquets, which bloom on trunks that can stand over 10 feet tall.

Lost Mine Trail: Set in the Chisos Mountains, this popular hike offers chances to see Havard agave, which have a stalk that torches with yellow blossoms in the late spring and early summer. Hikers also encounter other high-elevation cacti such as the Chisos prickly pear and claret-cup cactus, beloved for its bright red springtime flowers.

Rio Grande Village Nature Trail: This trail starts in riverside riparian habitat with boardwalks that extend across ponds before climbing up a limestone bluff where cacti that thrive in an exposed rocky environment live. See Schott club cholla, Comanche prickly pear, and eagle claw cactus.

Naturally Capable

Native people have inhabited the Big Bend region since the end of the last Ice Age. Their resilience is rooted in deep instincts about how to make the most of their natural resources, including the cactus and other needle-pointed plants that many of us today take caution to avoid.

“The plants have adapted to keep from freezing in the winter and drying up in the summer, and the people here have had to adapt in the same way,” says Enrique Madrid, a 76-year-old historian who lives in his family’s borderland home in Redford and traces his roots to Mexico and the Jumano Apache. “Cacti grow in clusters for protection, same as the people have survived by relying on their family units. You cannot survive alone in the desert.”

Native people have relied on desert plants and rocks throughout history, Madrid notes, such as using ocotillo stalks for roofing materials on circular rock homes. Limewater extracted from limestone enhances the nutritional value of corn tortillas. And, cactus fruit was an important food source—the strawberry pitaya was especially popular because it is abundant, easy to clean, and has small seeds.

When Madrid’s mother, who was born in 1913, got the Spanish flu in 1918, her parents wrapped heated prickly pear pads (the spines removed) in cloth and laid them on her chest like a compress to alleviate congestion and help her breathe. “There are lots of graves for children who died from the Spanish flu, but she survived,” Madrid says.

The sotol plant was also invaluable to desert dwellers. Often mistaken for agave because of its radiating spiny leaves, the durable sotol is part of the asparagus family. Native people would bake sotol stems in earthen ovens to make them edible.

Tom Alex, a retired archeologist who has worked for Big Bend National Park for 40 years, has excavated earthen pits where heated rocks and moist prickly pear pads were used to steam the sotol hearts.

“One of the things the Mescalero Apache would do is, once it’s cooked, they pounded it into flat cakes and then laid them out to dry in the sun,” Alex says. “Once it’s dried, you can break it up into pieces and it’s good for six months, like backpacking food or travel food.”

Sotol leaves were stripped for fiber to make rope, nets, baskets, and sleeping mats, along with fibers from lechuguilla agave and various yucca and grasses. At the Museum of the Big Bend in Alpine, an exhibit on La Junto de los Rios—the site of Native villages at the confluence of the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos near Presidio—displays woven sandals, bags, and straps. Also on display is an ancient sotol knife, which has the blade in the middle so the user could grip the tool with two hands to strip back the sotol leaves.

Madrid notes that sotol is also used to make a liquor of the same name. The process involves roasting and then distilling the hearts. People used to drink sotol to kill off viruses, such as the Spanish flu, Madrid says, “but I’m not sure how much that really helped.”

A Museum for Cacti

The diversity of Big Bend cacti is on colorful display at the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center in Fort Davis, home of the Maxie Templeton Cactus Museum.

The greenhouse features about 200 species, subspecies, and varieties of cacti and succulents. Biologists at Sul Ross State University started the collection in the 1970s with plants that were donated, collected in the field, or confiscated by customs officers at the border, says Powell, the Sul Ross professor emeritus of biology who was a co-founder of the nonprofit Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute in 1973.

In the late ’70s, the institute opened the nature center on the outskirts of Fort Davis. It’s now home to a botanical garden harboring native plants, hiking trails, a visitor center, bird blind, and mining exhibit. For cactus fans, the cactus museum is the highlight, says Lisa Gordon, the center’s executive director. A booklet guides visitors through displays organized by genera.

Adapted to the desert floor, the cacti grow in entertaining shapes—some look like piles of spiky meatballs; others stretch up on stems for attention. The thick long spines of the golden barrel cactus create a bright yellow orb, while the eagle claw and horse crippler cacti appear just as menacing as they sound.

“For a lot of people, when they drive through the desert it doesn’t look like much, but when they get a chance to see them up-close, they’re stunning,” Gordon says. “We get a lot of questions about how old the cactus are. People think they’re babies, but a lot of these are 30 years old or more.”

Though there’s often cacti in bloom in the greenhouse, springtime brings the most abundant flowers. March is also when the nature center hosts its annual Spring Break Cactus and Succulent Sale, scheduled for March 13-15. The sale features Chihuahuan Desert plants sourced from growers in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. For more info, visit cdri.org.

Agave to the Rescue!

Havard agaves go out with a bang. After storing up nutrients for about 20 years, the succulents muster a once-in-a-lifetime bloom, growing a 20-foot stalk adorned with bright yellow flowers that shine like yellow lanterns against the desert landscape. It’s the plant’s final act.

Before the agave wilts, however, its summertime flowers make copious nectar, which feeds numerous creatures and ensures the plant’s pollen will be spread for new agaves. One of the animals most reliant on the nectar is the Mexican long-nosed bat, an endangered species.

The bats summer in a cave in the Chisos Mountains of Big Bend National Park before returning to Mexico in the fall. To help ensure the bats’ survival, Austin-based Bat Conservation International embarked last year on a Havard agave restoration program in West Texas.

Kristen Lear leads BCI’s regional efforts, which include working with local partners to collect native agave seeds and growing seedlings to plant in the wild. It’s the extension of a program the group has been working on since 2018 in New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico.

“Agaves serve as a keystone species in their environment because the nectar provides food for hummingbirds, butterflies, and many species of bees and wasps,” Lear says. “We’ve even seen crows and ravens drinking from the nectar, and ringtails and mice. The agaves have a major impact on the biodiversity that’s out there.”

TH: When do the bats come to Texas?

KL: The Mexican long-nosed bats arrive in the spring, and the peak is in the summer because that’s when the peak agave bloom happens. They’re pregnant and lactating females that migrate to Big Bend National Park, and they actually give birth to their babies in the park.

TH: Where do they roost?

KL: It’s a cave in the Chisos Mountains, but it’s not something that people should visit because the bats are pretty sensitive to disturbance. As far as we know, it’s just one cave, but it’s such a rugged area, and there could be other caves we don’t know about.

TH: Why are the bats endangered?

KL: It’s two main things: roost loss, or disturbance to their caves where they historically live; and foraging habitat loss, or threats to agaves and other food plants.

TH: Where do the bats go from Texas?

KL: After the babies start to fly, we think the moms and babies fly up to the boot heel of New Mexico as a big group. Once fall hits, they migrate back south to Mexico. We don’t know the exact migratory route because these bats are hard to track. Part of the work we’re doing is trying to identify where that migratory corridor is so that we can work with landowners to protect it. We’re using some cool conservation technology, including eDNA, or environmental DNA, where we can swab the agave flowers to see if the bats have been there.

TH: Have you planted any agaves in Texas?

KL: Not yet. We’re working to develop relationships with partners to do eDNA surveys to identify the migratory corridor. We’ve also been working with our partners to collect wild agave seeds across the area, and we have some of those seeds growing in greenhouses at Sul Ross State University, for example. In two to three years, after they’re big enough to survive, we’ll go and plant those.

TH: Where will you plant the agaves?

KL: We’re working with the national park to see if we can plant there, but there are more regulations with national parks. These bats can travel 20 to 30 miles one way from their roost on a single night to forage. So we’re working with landowners and organizations outside the national park to restore agaves too.

TH: Are the agaves themselves in any danger?

KL: Climate change is the biggest threat. Hotter and drier summers, and longer periods of drought and extreme heat, can cause them to die, or to grow more slowly and not flower. Part of our work is looking for climate strongholds where the conditions into the future will remain favorable for agave growth and survival, as well as for the bats. It could be like higher elevations versus lower elevations. If we can bolster the populations of agaves in those climate resilient areas, we can then help create climate resilience in the system.