Editor’s Note: Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently “Stokely: A Life.” The views expressed here are his. View more opinion articles on CNN.

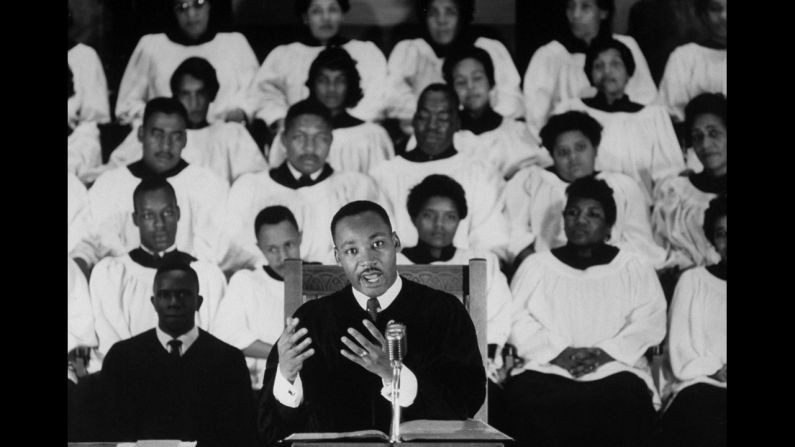

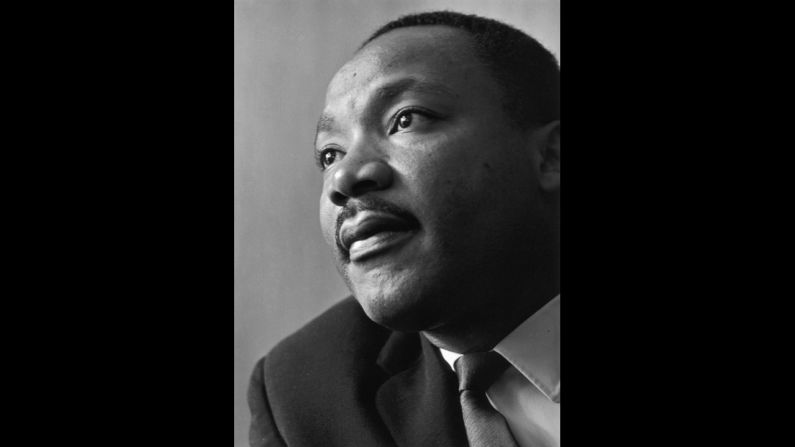

In 2020, the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday falls in a national election year, one that reminds us of the importance of voting rights, citizenship and political activism to the health of our democracy. King imagined America as a “beloved community” capable of defeating what he characterized as the triple threats of racism, militarism and materialism.

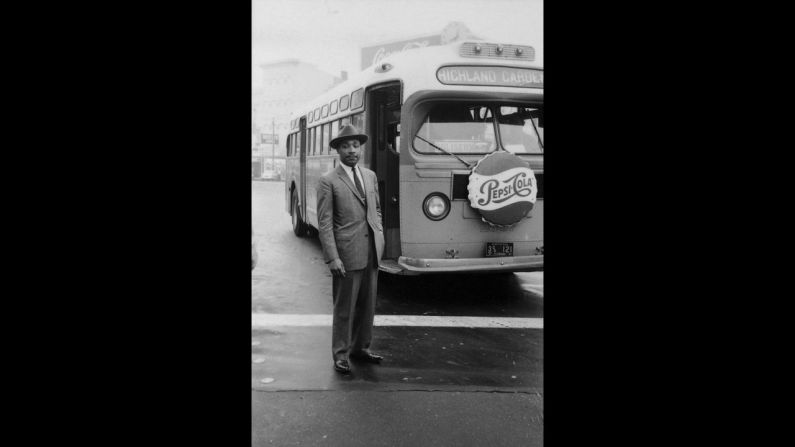

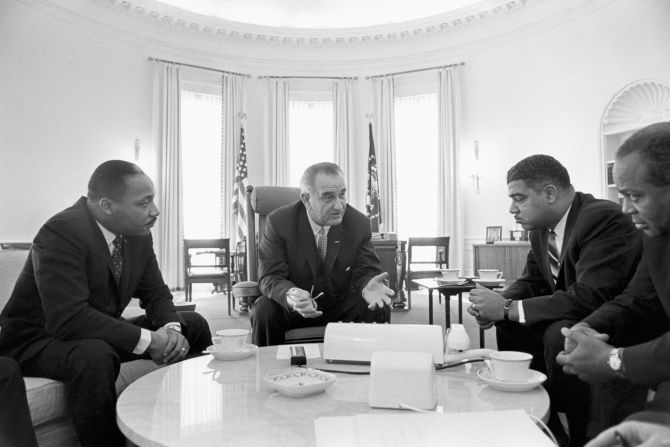

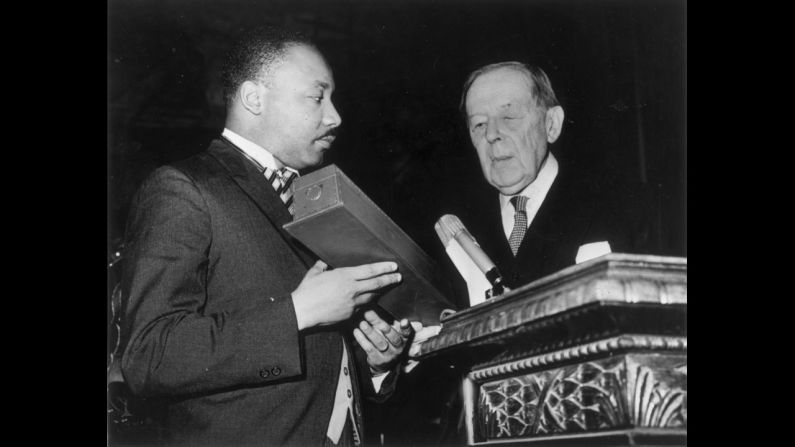

The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, alongside the 1954 Brown Supreme Court decision, represents the crown jewels of the civil rights movement’s heroic period. Yet King quickly realized that policy transformations alone, including the right to vote, would be insufficient in realizing his goal of institutionalizing radical black citizenship toward the creation of the “beloved community.” King argued that justice was what love looked like in public.

2020 also marks the 55th anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act, legislation that proved transformative for black citizenship, at least until the 2013 Shelby v. Holder Supreme Court decision that has helped enable the increase of voter suppression nationally. The most powerful way Americans can honor King now is through the pursuit of new national voting rights legislation that ends voter suppression and ID laws, allows prisoners to vote and automatically registers every 18-year-old citizen to vote.

Contemporary voting rights protection in America represents a failure of imagination and a threat to democracy. Grassroots movements, such as Moral Mondays in North Carolina, have worked to show how state legislatures have utilized the post-Shelby landscape to ensure anti-democratic majorities at the expense of genuine democracy and active voter participation. Proposed legislation, such as the the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019, seeks to restore the power of voting rights enforcement and other protections by establishing new rules that cover all states and allow for federal intervention in places with histories of active suppression over the previous 25 years.

Additionally, the VRAA bill would offer increased protection for indigenous voting populations such as Native Americans and Native Alaskan populations. Democrats in the House of Representatives successfully passed the VRAA (H.R.4.) in December, although the bill has virtually no chance of approval in a Republican-dominated Senate where elected officials pay lip service to King’s dreams even as they actively thwart their tangible political manifestations.

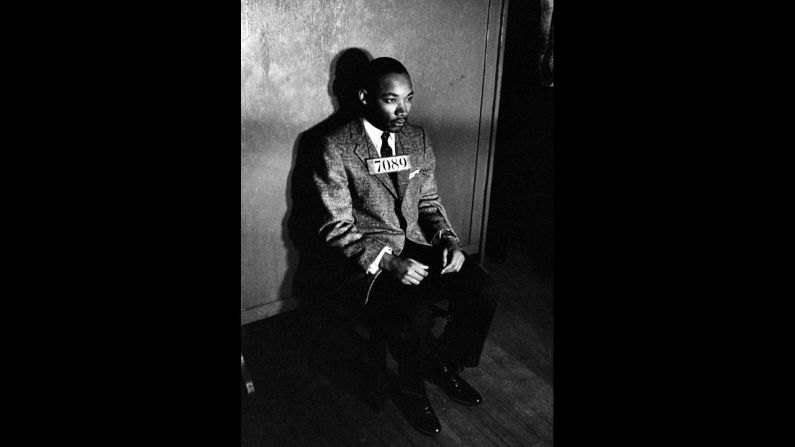

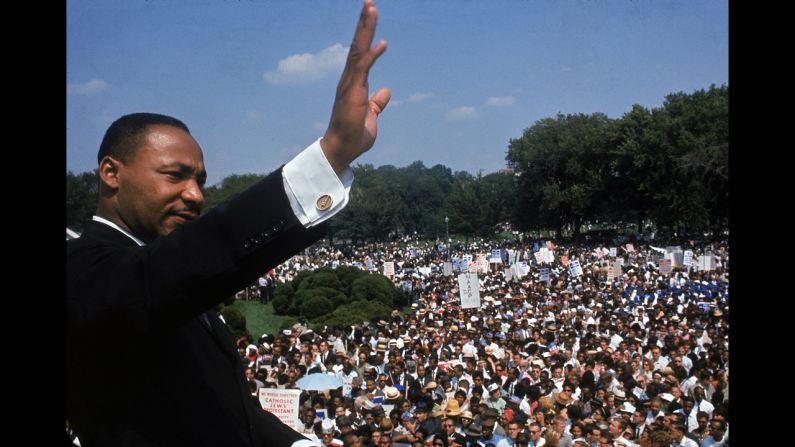

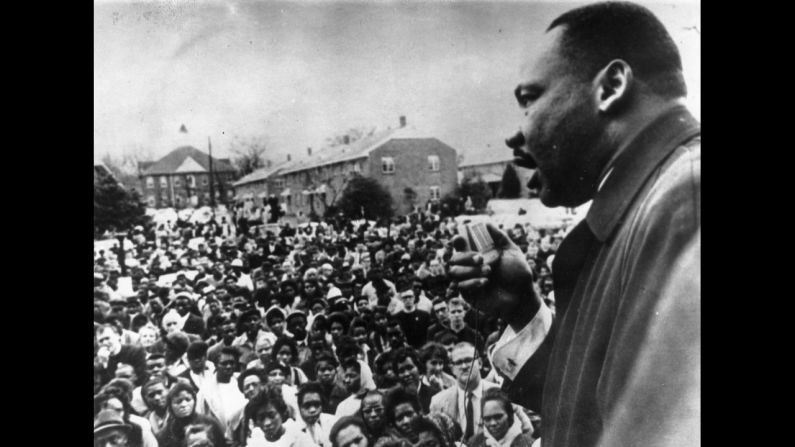

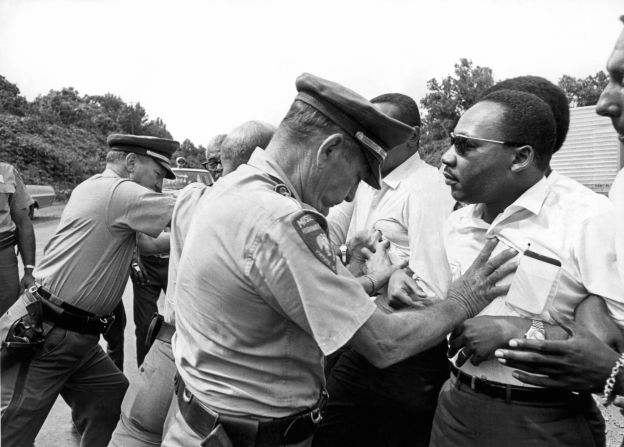

Voting rights for black Americans, for King, represented an important step toward reimagining a nation free of racial violence, segregation, poverty and hate. Civil rights demonstrations in Selma, Alabama in 1965 galvanized support for voting rights legislation, which was finally passed on August 6 of that year. Less than a week after the passage of this landmark legislation, the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles erupted in violence in the aftermath of police brutality. Racial violence in Watts shattered King, who visited the riot torn streets of Los Angeles.

King came to increasingly believe that the “beloved community” represented not simply the absence of racial oppression but the presence of justice in every facet of American life. There is a cruel irony in national celebrations of King’s legacy at the very moment where voter suppression is thriving across the landscape of American politics. The proliferation of voter ID laws, the purging of voter rolls and the passage of laws expressly designed to prevent blacks and people of color from exercising their franchise directly contradicts one of King’s greatest legacies.

Yet the radical citizenship that King advocated meant more than just voting rights. King defined citizenship as including voting rights, a living wage, adequate housing, access to health care, and excellent and racially integrated education. In contemporary America voting is one of the keys to opening up opportunity to racially segregated and economically impoverished communities of color. White Americans who disproportionately enjoy the positive benefits of citizenship are more likely than anyone to vote. Voting rights continue, well into the 21st century, to be one of the defining civil rights issues of our time, over a half century after that battle had been thought to have been won.

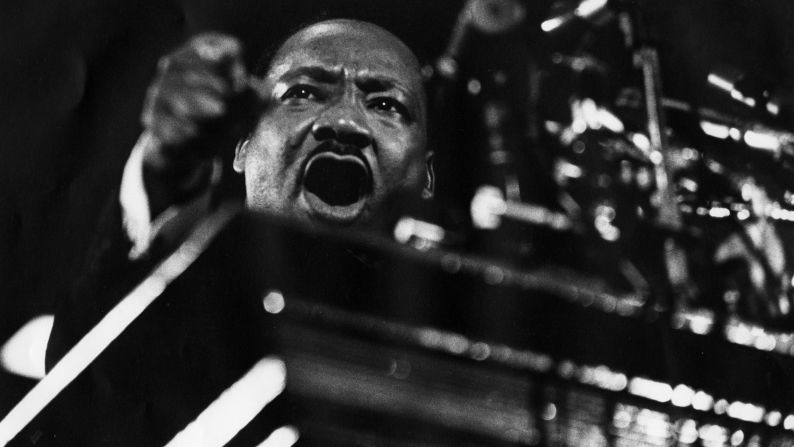

America’s celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. rests on the flawed understanding of his historic and contemporary legacy. Political leaders of varying ideological stripes embrace the most seemingly non-threatening aspects of King’s legacy, namely his Christian religious faith and philosophy of non-violence. Turning King into a sanctified figure shorn of rough political edges allows us to celebrate the civil rights movement as a children’s bedtime story, one with a happy ending.

That story demands simple heroes, villains, defeats, and ultimate victories. In popular culture, autobiographies, and media it plays out as a thrilling narrative but makes for poor history, lacking the subtlety, nuance, and ambiguities that in fact shaped King’s era and our own.

Such ambiguities help explain how we can commemorate King on the one hand even as we eviscerate his legacy on the other. The Martin Luther King Holiday too often serves as an acknowledgment of past achievements rather than recognition of the contemporary battles that King would be waging in our own time. Unfortunately, voting rights remain a major part of the unfinished social justice business of the present.