Abstract

In this study, the authors explore how young adults navigated the dual challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and jail reentry in a large urban environment. Fifteen young adults (aged 18–25) participated in up to nine monthly semi-structured interviews to discuss their experiences of reentry during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., spring and summer 2020). Participants held mixed attitudes and beliefs about COVID-19. Several participants viewed the pandemic as a hoax, while others took the pandemic more seriously, particularly if their friends and family members had contracted the virus. Yet nearly all participants viewed the pandemic as having a relatively minimal impact on their lives compared to the weight of their reentry challenges and probation requirements. Young adults described COVID-19 stay-at-home orders as limiting their exposure to negative influences and facilitating compliance with probation requirements. However, resource closures due to COVID-19, including schools, employment programs, and social services presented barriers to reentry success. The authors draw upon these findings to pose implications for interventions supporting young adult reentry.

Similar content being viewed by others

When the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in March 2020, nearly two million adults resided in local jails (Kang-Brown et al., 2021). Jail populations fluctuate daily, have a high turnover rate, and are disproportionately comprised of Black men and younger adults compared to the general population (Jones & Sawyer, 2019). While prison and jail populations declined at the beginning of the pandemic, local jails repopulated, leaving many incarcerated individuals in unsafe conditions and without adequate preparation for reentry into society during rapidly changing environmental circumstances (Kang-Brown et al., 2021).

Young adults (i.e., aged 18–25) comprise only 10% of the U.S. population, yet make up over 20% of the jail population (The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2015). Young adults held in local jails are highly vulnerable to poverty, unstable housing, unemployment, poor health outcomes, and the revolving door of incarceration (Brooks et al., 2006; Dumont et al., 2012; Riley et al., 2018). Moreover, young adults experience higher rates of jail recidivism compared to those over age 25 (Alper et al., 2018; Van Duin et al., 2021). Research has also found that up to 42% of young adults held in local jails have histories of mental health diagnoses, which increases the likelihood of recidivism (Hoeve et al., 2013).

U.S. jails typically provide scant reentry, employment, or behavioral health services (Freudenberg et al., 2005; Scheyett et al., 2009), and individuals with unmet health, mental health, and psychosocial needs repeatedly find themselves trapped in cycles with the criminal legal system (Fazel et al., 2016; Jones, 2020). Research has found that access to and utilization of community and social services (such as employment, education, and other programs) during reentry can reduce recidivism and provide a variety of prosocial supports to young adults (Mizel & Abrams, 2020; White et al., 2008). However, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns reduced the availability and accessibility of needed services, leaving young adults to manage their needs without adequate supports.

Given the recent nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, little is known about how young adults navigated jail reentry alongside the social circumstances wrought by COVID-19. Using longitudinal qualitative methods, this study explores how young adults navigated the dual challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and jail reentry in a large urban environment.

United States Jails and COVID-19

As early as March 2020, COVID-19 outbreaks occurred throughout jails and prisons in the United States (Akiyama et al., 2020; Franco-Paredes et al., 2020). In September 2021, California state prisons reported 50,565 confirmed COVID-19 resident cases, including 240 COVID-19 deaths among over 95,000 residents (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 2021). Among U.S. jails, those located in Los Angeles County (where this study took place) experienced the highest number of cumulative COVID-19 resident cases (5,463) and deaths (14) (UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars, 2021).

To reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission, states scrambled to decrease incarcerated populations (Marcum, 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). Between March and June 2020, state and federal prisons released more than 100,000 individuals (Sharma et al., 2020). Local jails also made efforts to decarcerate, and in approximately two months, Los Angeles County decreased its jail population by over 30% (Abraham et al., 2020). Though decarceration was meant to protect jail residents from contracting COVID-19, the sudden implementation of these policies resulted in increased homelessness (Kendall & Salonga, 2020). Due to the abruptness of pandemic-related releases, researchers have suggested that individuals released under these conditions faced more limited social service access and higher rates of unemployment, all of which contribute to increased risk for recidivism (Abraham et al., 2020; Kendall & Salonga, 2020).

Probation and reentry services during COVID-19

Jails have high turnover rates, at approximately 50% turnover per week (Minton & Zeng, 2021). Individuals are released from jails while awaiting trial (i.e., on bail) or are sometimes ordered a period of home probation monitoring after serving time in jail for a lower-level offense. The post-release probationary period commonly includes frequent check-ins with probation officers, drug tests, and participation in reentry services, such as mental health, parenting, education, and employment programs. Recent literature suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic altered the nature of probation services (Martin & Zettler, 2022). In many regions, in-person probation check-ins were replaced with remote communication such as telephone calls, video conferences, emails, and text messages (Schwalbe & Koetzle, 2021). According to limited recent studies, the overall rate of probation contact remained the same—and in some jurisdictions even increased—despite changes in the modes of communication (Schwalbe & Koetzle, 2021). The exact impact of these communication changes and extent to which released individuals had access to probation supervision or service referrals are largely unknown.

Studies have noted other pandemic-related changes to probation and parole, including decreased community-service requirements, revocation, technical violations, and drug testing (Viglione et al., 2020). According to Schwartzapfel (2020), social service closures pushed probation and parole officers to assume additional roles, such as helping their clients file for unemployment and find other resources. One study surveyed probation and parole officers from 43 U.S. states, finding that in response to COVID-19, clients experienced increased mental health challenges, higher rates of job loss, and more housing and food insecurity, with Black and Latinx clients reporting higher rates of food insecurity than White clients (Schwalbe & Koetzle, 2021).

While the course of the pandemic is still evolving, COVID-19 has exacerbated many of the difficulties that system-impacted individuals face during reentry, which may increase their risk of reincarceration and poor health outcomes (Desai et al., 2020). For example, due to pandemic-related closures, previously incarcerated individuals may face increased difficulties in obtaining jobs and vocational skills training (Desai et al., 2020). Other important resources and social services shut down for a period of time during the pandemic, making it more difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals to meet their basic needs (Dewey, 2020). Pandemic regulations may have also created unique barriers to creating positive social networks and engaging in health-promoting activities (Desai et al., 2020), which are important for young adults to successfully navigate reentry (Abrams & Terry, 2017). Ultimately, the impact of COVID-19 on young adults undergoing community reentry remains unknown.

Purpose of study

This exploratory study examines young adults’ experiences of navigating jail reentry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Young adults released from jail in spring 2020 had to contend with the challenges of reentry and probation requirements in rapidly changing social, environmental, and public health circumstances. Understanding the experiences of young adults undergoing jail reentry during the COVID-19 pandemic offers insight into how larger structural conditions—such as service accessibility and changes in probation services—shaped the challenges and opportunities of community reintegration. Moreover, given the rapid spread of COVID-19 in jails, this timely research explores how recently released young adults understood and responded to the virus itself. The specific research questions are: (1) How did young adults view and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic following their release from jail? (2) How did young adults experience the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to the challenges and opportunities of reentry and probation?

Method

Study Design

This qualitative longitudinal study examined the experiences of young adults (aged 18–25) who were released from jail and/or were on probation during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (June 2020-May 2021). As a university-based research team, we partnered with two Los Angeles County organizations that provided reentry support services to system-impacted young adults (described further below). Both agencies contributed to the study design and implementation. In addition, the study included a community advisory board comprised of six representatives from community-based reentry organizations, including leaders and social service providers with lived experiences of incarceration. Board members provided feedback on recruitment and data collection protocols so that our study was responsive to and considerate of the unique needs and experiences of system-impacted young adults.

Study Sites and Recruitment

We purposively recruited participants during the months of June and July 2020. The two partner agencies identified young adults and screened for study eligibility based on age (i.e., aged 18–25) and recent or ongoing involvement in the criminal legal system (i.e., recently released from jail and/or currently on probation). Additional eligibility criteria included: (a) fluency in English or Spanish and (b) lack of severe cognitive impairment. Overall, we experienced a 50% participation rate among those invited to participate. The recruitment protocols for each site are detailed below.

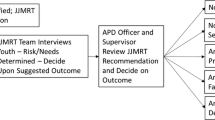

Program 1 was a county health services reentry program that offered pre- and post-release support in the county jails and connected individuals to needed healthcare and social services upon reentry. Participants recruited in partnership with Program 1 were originally enrolled in-person (i.e., while in jail) as part of a larger longitudinal study examining health and social networks during reentry. When enrolling in the larger study, participants provided contact information and consented to being contacted about future research. Our team used the provided information to invite participants to enroll in the current qualitative study. If participants provided contact information for a monolingual Spanish speaker (e.g., a parent or other relative), a native Spanish speaker on our team contacted the listed person to explain the study and coordinate contact with the young adult. We clarified that participation in the qualitative study was independent of participation in the larger study.

Program 2, a community-based organization, provided a variety of reentry supports to system-impacted youth and young adults in Los Angeles County, including career and educational development, mentorship, and wraparound services. Program 2 staff approached young adults who met the general criteria outlined above. We experienced some recruitment barriers due to the absence of a face-to-face connection with participants, as well as lower than usual turnout at community agencies that were shutting down or transitioning to remote services. Based on our need to enroll participants at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we expanded eligibility criteria to include young adults on probation, irrespective of when they had been released from jail. If interested, Program 2 provided eligible young adults’ contact information to our study team. We then contacted young adults to confirm interest and eligibility.

Protection of human subjects

The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (DHS) and our University’s institutional review board (IRB) approved all procedures. Verbal consent for all participants was obtained via audio or video call. In all interactions, we emphasized that study participation would not affect their standing with probation, the court, or health and reentry services.

Sample

We sought to recruit 10–15 participants for this longitudinal study and in all, 15 young adults participated in the study. We found this number to be sufficient to provide diverse views of reentry and COVID-19 experiences during this critical time period. At the juncture of enrolling the 15 participants, the team decided to focus on depth (i.e., repeated interviews over time) rather than breadth. Table 1 provides summary demographic information for the sample, and Table 2 provides demographics and study information for each individual participant, including age, race, and number of completed interviews. As shown in Table 1, the sample was mostly male (n = 13, 86.7%), and all participants (n = 15) identified as either Black (n = 9, 60.0%) or Latinx (n = 6, 40.0%), with one Latinx participant identifying as biracial (Mexican and White). Though we did not purposively sample based on race or ethnicity, our sample reflects the disproportionate representation of Black and Latinx males in Los Angeles County jails, who comprised 84% of the jail population in 2020 (Los Angeles Almanac, n.d.).

There were minimal differences between Program 1 (n = 6) and Program 2 (n = 9) participants. Program 1 participants were slightly older, at a mean age of 22.6-year-old, compared to Program 2 participants who were 19.5 years old on average. Program 1 participants also predominantly identified as Latinx (n = 5 of 6, 83.3%), while participants from Program 2 predominantly identified as Black (n = 8 of 9, 89.0%). Finally, at the time of recruitment, Program 1 participants had exited jail more recently, as they were recruited for the larger study while incarcerated. Still, most participants (n = 10) were within their first six months of reentry at the time of their first interview, with participants on average being 3.6 months into reentry at the onset of data collection.

Data Collection

We invited the young adults to participate in a series of longitudinal, semi-structured interviews once a month for up to nine interviews. The interview guide (Appendix A) covered three principal areas related to participants’ experiences of reentry during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) health and wellbeing during the pandemic; (2) reentry experiences and support during the pandemic; and (3) other experiences during the pandemic. To provide flexibility and promote continued engagement, participants selected the date, time, and medium (audio or video call) for each interview. Given the difficulty of recruiting and retaining justice-involved young adults in longitudinal studies (Abrams & Terry, 2017), we allowed participants to miss interviews and/or have gaps between data collection greater than one month while still remaining in the study to promote retention during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In total, we conducted 65 interviews with 15 unique participants (described in Table 2) between June 2020 and May 2021. On average, participants completed four interviews, with two-thirds (n = 10, 66.6%) completing four or more interviews. One-third (n = 5, 33.3%) of participants completed just one interview, and about one-fourth (n = 4, 26.7%) completed all nine interviews. Interviews typically lasted between 15 and 60 min, with the average interview lasting about 30 min. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and checked for accuracy. Participants received $25 in cash or gift card (their choice) for each interview.

Analysis

We conducted inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of the interviews, using Dedoose Software (Version 8.3.35, 2020) for data storage and retrieval. To begin analysis, we used an open coding process with four randomly selected interviews to develop a preliminary codebook. Three researchers on the team then applied the preliminary codebook to selected interviews, double-coding transcripts to confirm mutual understanding of codes and definitions. Our team continued to meet regularly to resolve all coding disagreements and refine the initial codebook. Once finalized, three team members applied the codes to all interviews.

Once coding was complete, the next step involved making meaning of the codes to identify concepts and themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To begin this process, we organized all coded segments by participant and interview number. For each participant, we then read all coded segments within the context of their interviews to write descriptions of the circumstances related to the coded segments. Next, we examined codes by participant and used written descriptions to generate a summary of each young adults’ overall experience of reentry during the pandemic. We then used summaries to organize codes into three broad categories: (a) COVID-19 Beliefs and Attitudes, (b) COVID-19 Behavior Change, and (c) COVID-19 Personal and Reentry Impact. Through team discussion, we continued to iterate on the organization of codes (e.g., collapsing redundant codes, breaking out unique codes, grouping similar codes, etc.) until we arrived at an organization of codes that reflected the experiences of our participants. Table 3 contains the code map and the final organization of categories and codes.

Results

COVID-19 Beliefs and Attitudes

Participants’ beliefs and attitudes about COVID-19 are clustered into two main categories: (1) Beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) COVID-19 life relevance (see Table 3). The first cluster, “Beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic,” refers to young adults’ views and understandings on COVID-19 as a disease. The second cluster, “COVID-19 life relevance,” refers to attitudes surrounding the pandemic in relation to their own life experiences.

Beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic

Interviewees expressed an array of beliefs about COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic and throughout the study. Their beliefs ranged from perceiving the pandemic as a hoax to viewing the pandemic as a serious health concern. Young adults’ beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be shaped by both their personal experiences with the virus as well as their relevant sources of information.

Early in the pandemic (spring and summer 2020), four participants expressed strong beliefs that the COVID-19 pandemic was a hoax and/or a lie perpetuated by government. These beliefs tended to stem from sources of information within their own social network, such as family and friends, rather than information from news outlets and government officials. For example, Ryan expressed skepticism about the pandemic when stating:

I feel like it’s just a big old whole—like a big old fake scandal, you know? Because I’ve asked a lot of different people and none of them have—all of them tell the same thing that they don’t know anybody that’s sick, or if they do, that nothing ever happens to them, you know? Like all these fake death things are—the numbers at the beginning—like I think they’re fake, you know? (July 2020)

Like Ryan, other participants formed their opinions of the pandemic based on conversations with people within their communities and personal experiences with COVID-19 among their friends and families. Another young adult, Jared, doubted the legitimacy of the pandemic based on the information he learned from the movie “Contagion,” an action thriller that depicts a global pandemic. In comparing the dramatization of a pandemic in “Contagion” to his lived experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, Jared interpreted the discrepancy between the two as the news reporting on the pandemic being exaggerated and alarmist.

In January 2021, almost a year after the onset of the pandemic, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved the emergency use of vaccines. Participants who questioned the severity or legitimacy of the pandemic were likewise skeptical of the safety or promise of the vaccines. For example, Bryan viewed the COVID-19 vaccine as incongruent with his religious beliefs and a method of government control. Ashley, expressed similar feelings and described the vaccine as indicative of a government’s supposed desire to exert power on citizens:

We’re not government affairs, so how are we going to find out what’s really going on, but listening to what they want us to hear… This [pandemic] might be another distraction… And like a lot of things are deceiving. So, nothing you could do, but live your life… You can’t stop the government from lying (February 2021).

As Ashley expressed, participants’ skepticism towards the vaccines and government messaging about the pandemic appeared to stem from a general distrust of institutions.

Six young adults also communicated doubts about the seriousness of COVID-19, regarding both the length and severity of the pandemic. During the first year of the pandemic, Steven predicted that the pandemic would only last for a few months and that people would eventually forget about it, using the Ebola virus as a comparison:

A couple months after Ebola, everybody pretended like it never existed. So, I think it’s going to be to the point, either in a few years or a few months, maybe it could even be next year, I don’t know, but everything is going to be forgotten (October 2020).

Yet over time, Steven became more concerned about the spread of COVID-19 after seeing people in his life contract the virus. He witnessed one friend and two family members contract and suffer from COVID-19. He later reflected, “It just kind of makes me want to be more careful about, ah, sanitize my hands. I don’t like to be around a lot of people anyways, so I just distance myself way more” (January 2021). Seeing people in his life contract the virus legitimized the pandemic to Steven, which then led him to hold more cautious and serious attitudes towards COVID-19. Similarly, Michael explained how his beliefs evolved over time:

I didn’t understand [the pandemic]. I thought it was a joke. Until everybody—I seen everybody with their masks, and they like, ‘Oh, you can’t come in.’ You couldn’t walk in certain stores without a mask. And I’m like, ‘Wow! This thing’s serious’ (April 2021). As the pandemic progressed, participants experienced visible changes in their everyday lives, which for some, changed their views on the severity of the pandemic. Overall, participants’ attitudes towards COVID-19 shifted over time and were shaped by their firsthand experiences and the changes they experienced and witnessed within their proximal environments.

COVID-19 life relevance

Though all participants experienced changes in their environments in response to COVID-19 and related public health measures, they did not view the pandemic as a major issue for them personally. Rather, they expressed that reentering society demanded all their focus and attention, making COVID-19 feel relatively unimportant compared to other facets of their lives. Almost all participants (14 of 15) conveyed ambivalence towards the pandemic’s influence on their lives and believed it to have an overall negligible impact on their personal circumstances. When asked about personal impacts of COVID-19, Steven replied, “It’s not really no major change on me” (June 2020). Similarly, Jared expressed, “It was a minor thing, but… no major disruptions. You know, everything’s been pretty calm” (July 2020).

Generally, these young adults did not feel strongly about the impact of COVID-19 on their lives. Three participants explicitly expressed that COVID-19 was irrelevant to them personally, particularly compared to the challenges of reentry. They stated that the pandemic minimally affected their everyday lives and that they ignored it. For example, Ryan stated, “Yeah, I’m already used to [the pandemic]. It’s not that big of a deal” (July 2020). Rather than viewing the pandemic as a major barrier or disruption, Ryan viewed it more as something that existed as the backdrop to his reentry. Similarly, nine participants conveyed a “this is fine” attitude, meaning they acknowledged the pandemic’s impact on their daily lives but viewed it as a relatively minor disruption when compared to their other challenges. For example, one young adult shared, “In terms of the pandemic, you know, it’s a slight adjustment” (John, July 2020). Overall, the young adults were generally indifferent towards the pandemic and viewed it as relatively insignificant in the broader context of navigating reentry.

COVID-19 Behavior Changes

This group of codes refers to how participants changed their behaviors in relation to COVID-19. All participants reported that they changed at least some aspects of their behavior to adhere to COVID-19 restrictions, including wearing masks and social distancing. However, participants differed in their opinions and difficulties related to following safety guidelines. For example, Bryan reported that, “Sometimes [I] can’t afford the mask and stuff like that… So it’s just a hassle” (June 2020). Participants viewed masks as yet another expense they had to bear to participate in society and complete essential tasks, such as grocery shopping and seeking social services. However, early confusion and mixed messaging regarding COVID-19 led to doubt surrounding the effectiveness of wearing masks. Months after the onset of the pandemic, Bryan asked an interviewer, “Do you really think this mask is going to protect you from coronavirus, bro? If you’re going to catch corona, you was destined to get that shit, dawg… mask [or] no mask” (November 2020). Thus, participants’ beliefs influenced their behavioral responses to COVID-19. Young adults who did not trust public information regarding safety guidelines surrounding the pandemic remained skeptical about masks and other measures throughout the duration of the study.

Participants recalled how they learned about COVID-19 while in jail and the steps taken to prepare them to navigate the pandemic once released into the community. Isaiah recalled that jail staff gave him an overview of precautionary measures, including staying six feet away from others, wearing a face mask, and washing his hands frequently. However, Marcus had a different experience, relaying that while in jail, “I saw [the pandemic] in the news. [The staff] didn’t tell us nothing, so when I got out, [that’s when] I found out everything” (July 2020). Josh similarly expressed that, during incarceration, he received information about the pandemic from watching the news rather than from jail staff. There was a wide variety of messages received in jail that were often inconsistent.

Upon release, some of the young adults were able to live with and quarantine their families during the height of the early pandemic. However, others could not return home due to their family’s fear of the participant acting as a disease vector because they were coming from jail. Ryan recalled, “My family doesn’t want me to go to the house… They were scared that, since I barely came out of jail, I was with a bunch of infected people” (July 2020). Others compared COVID-19 safety measures to their experiences in jail. Sam stated that stay-at-home restrictions were “just like being in jail [but] on the outside” because he had to follow strict rules and was unable to move about freely (July 2020). Although participants practiced some COVID-safety protocols, they were experienced as largely inconvenient. Overall, there was wide variation in how young adults received an understood information and changed their behaviors in response to the pandemic.

COVID-19: Personal and Reentry Impact

This set of codes refers to the ways that participants were personally impacted by the pandemic. Participants described both positive and negative ways in which the pandemic impacted their lives during reentry. Additionally, they shared mixed views on the increased reliance on a virtual world (e.g., Zoom and Google Classroom) for education, social services, and probation communications.

Negative impact of COVID-19 pandemic

The young adults all shared negative experiences related to the pandemic. COVID-19 impacted their ability to successfully reenter society, meet probation requirements, and pursue personal goals. Just three participants described direct virus contact where they or someone they knew contracted COVID-19. Two young adults reported family members passing away from COVID-19, including Josh whose mother died.

Beyond direct impact due to illness or death, participants discussed the negative emotional and environmental impacts of COVID-19. They described distress and loneliness throughout the pandemic as they isolated from friends and family. In addition, five participants felt that their reentry goals were delayed due to pandemic-related changes. Jared shared, “I just need to get [my legal cases] all taken care of. And this whole COVID thing—they keep pushing back my court dates. And the whole COVID thing—it really looks like it’s starting to delay things” (December 2020). At his next interview, Jared continued to report delays in court processing, “COVID [is] making the court system slow… It is causing a delay… Because I went to the booth, and they told me that they’re not taking any new court cases.” (January 2021). Other participants reported similar delays with legal proceedings and court dates.

Additionally, 14 participants attributed reduced opportunities to COVID-19. Participants described difficulties securing employment and reported that several businesses had closed, laid off staff, and/or paused hiring during the pandemic. For example, Ryan stated that, “Because of coronavirus, I wasn’t able to get a job quick. You know, it’s been difficult. It’s not the same as before… Everything’s closed and people are tripping because of this pandemic… There’s not really no interviews going on” (July 2020). Similarly, David reported, “It’s frustrating cause I was trying to get my ID so I could start working and stuff, [but] I can’t even do that” (July 2020). David needed an identification card to secure a job but was unable to schedule an appointment, which made it more difficult to pursue employment goals and meet his needs.

Overall, participants were focused on completing their probation requirements and pursuing other reentry-related goals. Twelve participants reported closures of needed social services or other resources they would have been able to access if not for the pandemic. Ryan explained that the reentry programs he sought out were closed, such as a housing services office. Isaiah, who lived with a friend prior to incarceration, reported that his friend’s family threw out his belongings because Isaiah was in jail for an extended period. As such, Isaiah was “nervous because, oh, I’m coming home. COVID got the stores shut down. What am I gonna wear? So, I came home in a jumpsuit” (June 2020). Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected even some of the most basic facets of reentry.

Positive impact of COVID-19 pandemic

Despite these reported challenges, nearly half of participants described positive impacts of COVID-19 and stay-at-home orders, including reduced temptation to engage in risky behaviors such as substance use. Some also reported improved family relationships. For example, Michael felt that the pandemic “[brought] families together… [With the] pandemic, you can’t go out. You can’t go nowhere… It’s been bringing a lot of family together. It’s been cool… When the pandemic wasn’t around, everybody was doing their [own] thing” (September 2020). Ashley presented COVID-19 financial assistance as a positive aspect of the pandemic. She stated the pandemic “helped drastically because they’re giving away free money… now you don’t have to be in-person and there’s different things you could bypass… like you could do things virtual now” (April 2021). These positive aspects were often experienced alongside negative aspects; in that, one set of experiences did not negate the others.

Virtual world (mixed impact)

Due to COVID-19 health and safety measures, numerous services and resources migrated to virtual platforms. This “virtual world” appeared to have a mixed impact in that some young adults felt they benefited from the increased technology utilization, while others described trouble adjusting. For example, Bryan expressed difficulty with distance learning and said:

I’m really nervous… because I’m not an online geek person. So, we not able to be on campus. It’s very hard to get in contact with all my teachers and fill out the registration forms and having [to] sign signature online… So, I’m really just stressed out right now (August 2020).

As education moved to distance learning, participants realized that they would need to alter their approach to school or obtain additional materials, such as expensive computers. Additionally, some interviewees conducted their court and probation appointments via audio or video call instead of in person visits. Jared had mixed feelings about virtual court and felt the increased accessibility came at the cost of accountability:

[It’s] weird but also a lot more safer if you ask me. I’ll be at home talking to the judge at home… You can’t lock me up from home, dude… [But at the same time] I think some things should be left as the original, plain way you should always do them. Like video court, I don’t think they should continue that after COVID… I don’t think it’s necessary (February 2021).

Though Jared felt safe attending court in his home, he also recognized that virtual court was not ideal and expected criminal proceeding to return to a “normal” state following the pandemic. Some participants described virtual court as more accessible than in-person proceedings, while others found remote court hearings troublesome. Though virtual court meetings mitigated transportation barriers, technology utilization in the form of distance learning deterred many from attending school. Thus, pandemic-related shifts to a virtual world had both positive and negative impacts for young adults depending on the medium, implementation, and context.

Discussion

Our first research question asked how young adults reentering the community from jail viewed and responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis identified a range of beliefs rooted in young adults’ sources of information and personal experiences. There was wide variation in the information, or lack thereof, that participants received about COVID-19 while in jail. Some noted that their only source of information about the pandemic came from watching televised news in jail recreation rooms rather than direct education from staff. U.S. jails and prisons are well known for their small, confined spaces and overall unsanitary conditions, all of which contributed directly to the spread of COVID-19 (Simpson et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2020). We found that participants were inadequately informed about the COVID-19 virus, including the associated health risks and mitigation strategies. This absence of information perhaps contributed to many participants initially minimizing the severity of COVID-19 and related safety measures.

Perceptions of COVID-19 gradually changed as the young adults transitioned into a society that was shut down. Participants’ beliefs about the pandemic mirrored public attitudes (Christensen et al., 2020), ranging from seeing the pandemic as a hoax to understanding it as a serious concern. The more unique aspect of our findings was that interviewees described the pandemic as relatively insignificant in the context of their lives. “It was there when I came home” conveys this central finding that young adults viewed the COVID-19 pandemic as having minimal impact on their own lives in relation to the challenges of reentry. Their perception makes sense when considering the number of urgent issues that young adults face during reentry, including unemployment, homelessness, and burdensome and layered probation requirements (Abrams & Terry, 2017). The challenges of reentry eclipsed the pandemic as a primary concern.

Our second research question asked how young adults experienced the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to the opportunities and barriers of reentry. For this question, there were mixed findings, as the pandemic influenced the lives of participants and their ability to navigate their reentry in both positive and negative ways. Positive aspects included financial relief (i.e., stimulus checks) and the virtual world helping the participants avoid recidivism by staying home and expanding accessibility. While related literature on young adults’ reentry experiences during COVID-19 is evolving, our findings align with the broader reentry literature suggesting that reducing risk of recidivism during reentry often means young adults must avoid places, friends, and other influences that facilitate criminal activity (Abrams & Terry, 2017). Participants believed that virtual court was a positive aspect of the pandemic, as they reported feeling safer attending court remotely and benefited from increased accessibility to court and probation. Our study aligns with recent literature that supports the continued use of virtual court to increase all constituents’ access to court proceeding and enable lawyers to better reach the communities they often struggle to serve (Bannon & Keith, 2021).

Conversely, some of the negative components of the pandemic related to personal loss, emotional isolation, and the general inaccessibility of fractured social services and other reentry resources. The young adults felt the pandemic further restricted their access to reentry services and ability to meet basic needs, such as obtaining food and clothing. In response, researchers have called for reentry and social services to adapt and change to provide more nuanced, accessibility-driven, and personalized support that better serves those leaving jails and prisons (Desai et al., 2021). Some participants felt that COVID-19 safety restrictions felt like an extended version of jail in that they were forced to remain in a confined space. The emotional toll of the pandemic on these young adults likely mirrors the feelings that many people experienced: loss, isolation, and uncertainty (Le & Nguyen, 2021). Still, the stakes are high for young adults on probation to who need to meet their basic needs upon release to avoid situations that can lead to recidivism. As such, any additional emotional toll or logistical challenge can represent a critical setback for young adults during reentry.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this study, and the results should be interpreted as exploratory. This is a qualitative study based on 15 participants that is not transferable to other regions that may have experienced different pandemic-related policies and restrictions. Moreover, there was an uneven number of interviews per participant, such that young adults with greater participation may have influenced findings more than those with fewer interviews. While we worked to account for differential interviews in our analysis, it remains a limitation that individuals who dropped out of the study may have experienced more COVID-19- and reentry-related hardships. While the longitudinal design is a strength of the study, the unevenness in the number of interviews and attrition rate remains limitation.

Implications

In this longitudinal study of reentry during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the young adults perceived connections to friends, family, and supportive programs as beneficial to their health and reentry success. While this is not a new finding around young adults and reentry (Martinez & Abrams, 2013; Mizel & Abrams, 2020), it emphasizes the importance of social support during reentry, particularly for the young adult population where reentry plans and services do not always integrate developmental considerations or acknowledge the importance of parental and/or caregiver ties (Uggen & Wakefield, 2008).

Moreover, due to the lack of health information and poor conditions in jail, the young adults were not adequately prepared to contend with COVID-19 health risks upon their release. Though this finding is not necessarily surprising, it does relay the importance of emphasizing public health in carceral programming and reentry preparation (Howell et al., 2020). Even in the absence of the COVID-19 pandemic, people who have spent time in jail or prison are at a higher risk for infectious diseases (Bick, 2007). Future research might consider the extent to which correctional staff are equipped to prepare people for the public health aspects of reentry.

The young adults in our study felt unprepared for remote learning technology and distance education, despite their familiarity with technology more generally. As the impacts of the pandemic continue to ripple through society, education programs are continuing to experiment with various forms of distance learning (Schwartz et al., 2020), and jails can serve as a potential site to train young adults in using this technology. Moreover, improved implementation of these technologies within carceral facilities could help bridge gaps in the continuity of education for incarcerated individuals (Bondoc et al., 2021). Continued utilization and advancement of remote technologies might similarly address continuity of care (e.g., telehealth and behavioral healthcare) and employment opportunities (e.g., Zoom interviews), while somewhat mitigating the disruptive and damaging impacts of incarceration. As such, carceral facilities and reentry services might use lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic to address longstanding barriers to reentry that have resulted in unjust suffering and persistent inequity for incarcerated young adults.

Conclusions

This study used a longitudinal qualitative design to explore how young adults experienced COVID-19 as they reentered their communities following release from county jail. Findings indicate that the pandemic was relatively unimportant to these young adults compared to pressing tasks related to reentry and probation. While this study has several limitations, its strength lies in capturing real-time data during an unprecedented public health crisis that unfolded rapidly and with great uncertainty. As such, the study provides a unique perspective on reentry during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should examine the pandemic’s toll on young adults and reentry as it relates to their ability to complete educational and vocational programs, along with the successful completion of probation. Moreover, researchers may wish to assess how the pandemic altered the ways probation services surveil and relate to young adults and if these changes impacted recidivism and/or other reentry outcomes. Overall, given the sweeping impact of COVID-19 on all aspects of society, more research is needed to understand how incarcerated young adults navigated reentry and probation during this period of rapid social change.

References

Abraham, L. A., Brown, T. C., & Thomas, S. A. (2020). How COVID-19’s disruption of the U.S. correctional system provides an opportunity for decarceration. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 780–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09537-1

Abrams, L. S., & Terry, D. (2017). Everyday Desistance: The Transition to Adulthood Among Formerly Incarcerated Youth. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press

Akiyama, M. J., Spaulding, A. C., & Rich, J. D. (2020). Flattening the curve for incarcerated populations — Covid-19 in jails and prisons. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(22), 2075–2077. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2005687

Alper, M., Durose, M., & Markman, J. (2018). 2018 Update on prisoner recidivism: A 9-year follow-up period (2005–2014) (NCJ 250975). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/18upr9yfup0514.pdf

Bick, J. (2007). Infection control in jails and prisons. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 45(8), 1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1086/521910

Bannon, A. L., & Keith, D. (2021). Remote court: principles for virtual proceedings during the covid-19 pandemic and beyond. Northwestern University Law Review, 115(6), 1875–1920

Bondoc, C., Meza, J. I., Ospina, B., Bosco, A., Mei, J., E., & Barnert, E. S. (2021). Overlapping and intersecting challenges”: Parent and provider perspectives on youth adversity during community reentry after incarceration. Children and Youth Services Review, 125, 106007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106007

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, L., Visher, C., & Naser, R. (2006). Community residents’ perceptions of prisoner reentry in selected Cleveland neighborhoods. Urban Institute Justice. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.507 .372&rep=rep1&type=pdfPolicy Center

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (2021, October). Monthly Report of Population as of Midnight September 30, 2021. https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/174/2021/10/Tpop1d2109.pdf

Christensen, S. R., Pilling, E. B., Eyring, J. B., Dickerson, G., Sloan, C. D., & Magnusson, B. M. (2020). Political and personal reactions to COVID-19 during initial weeks of social distancing in the United States. PLOS ONE, 15(9), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239693

Desai, A., Durham, K., Burke, S. C., NeMoyer, A., & Heilbrun, K. (2021). Releasing individuals from incarceration during COVID-19: Pandemic-related challenges and recommendations for promoting successful reentry. Psychology Public Policy and Law, 27(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000279

Dewey, C. (April 16, 2020). “Released early to thwart COVID-19, ex-offenders confront hunger outside.” The Counter. https://thecounter.org/early-release-hunger-homelessness-covid-19/

Dumont, D. M., Brockmann, B., Dickman, S., Alexander, N., & Rich, J. D. (2012). Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 325–339

Fazel, S., Hayes, A. J., Bartellas, K., Clerici, M., & Trestman, R. (2016). Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(9), 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0

Franco-Paredes, C., Jankousky, K., Schultz, J., Bernfeld, J., Cullen, K., Quan, N. G. … Krsak, M. (2020). COVID-19 in jails and prisons: A neglected infection in a marginalized population. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(6), e0008409. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008409

Freudenberg, N., Daniels, J., Crum, M., Perkins, T., & Richie, B. (2005). Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325

Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2013). The influence of adolescent psychiatric disorder on young adult recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(12), 1368–1382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813488106

Howell, B. A., Batlle, R., Ahalt, H., Shavit, C., Augustine, S., Wang, D. … Williams, E. (2020). B. Protecting decarcerated populations in the era of COVID-19: Priorities for emergency discharge planning. Health Affairs Blog, 13, 2020

Jones, A. (2020, March). The “services” offered by jails don’t make them safe places for vulnerable people.Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/03/19/covid19-jailservices/

Jones, A., & Sawyer, W. (2019, August). Arrest, release, repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems.Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/repeatarrests.html

Kang-Brown, J., Montagnet, C., & Heiss, J. (2021). People in jail and prison in 2020. New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2021. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/people-in-jail-and-prison-in-2020.pdf

Kendall, M., & Salonga, R. (2020, April 27). Coronavirus: Mass jail, prison releases leave some Bay Area inmates on the streets. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/04/27/coronavirus-mass-jail-prison-releases-leave-some-inmates-on-the-streets/

Le, K., & Nguyen, M. (2021). The psychological consequences of COVID-19 lockdowns. International Review of Applied Economics, 35(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2020.1853077

Los Angeles Almanac (n.d.). “Los Angeles County Jail System by the Numbers.” Retrieved from: http://www.laalmanac.com/crime/cr25b.php

Marcum, C. D. (2020). American corrections system response to COVID-19: An examination of the procedures and policies used in spring 2020. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09535-3

Martin, K. D., & Zettler, H. R. (2022). COVID-19’s impact on probation professionals’ views about their roles and the future of probation. Criminal Justice Review, 47(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/07340168211052876

Martinez, D. J., & Abrams, L. S. (2013). Informal social support among returning young offenders: A metasynthesis of the literature. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57(2), 169–190

Minton, T. D., & Zeng, Z. (2021). Jail Inmates in 2020 – Statistical Tables (NCJ 303308). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji20st.pdf

Mizel, M. L., & Abrams, L. S. (2020). Practically emotional: Young men’s perspectives on what works in reentry programs. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(5), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2019.1617225

Riley, R., Kang-Brown, J., Mulligan, C., Valsalam, V., Chakraborty, S., & Henrichson, C. (2018). Exploring the urban–rural incarceration divide: Drivers of local jail incarceration rates in the United States. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 36(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2017.1417955

Scheyett, A., Vaughn, J., & Taylor, M. F. (2009). Screening and access to services for individuals with serious mental illnesses in jails. Community Mental Health Journal, 45(439), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9204-9

Schwalbe, C. S. J., & Koetzle, D. (2021). What the COVID-19 pandemic teaches about the essential practices of community corrections and supervision. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(9), 1300–1316. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548211019073

Schwartz, H. L., Grant, D., Diliberti, M. K., Hunter, G. P., & Setodji, C. M. (2020). Remote Learning Is Here to Stay: Results from the First American School District Panel Survey. Research Report. RR-A956-1. RAND Corporation

Schwartzapfel, B. (2020, April 3). Probation and parole officers are rethinking their rules as COVID-19 spreads. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/04/03/probation-and-parole-officers-are-rethinking-their-rules-as-coronavirus-spreads

Sharma, D., Li, W., Lavoie, D., & Lauer, C. (2020, July 16). Prison populations drop, but not because of COVID-19 releases. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/07/16/prison-populations-drop-by-100-000-during-pandemic

Simpson, P. L., Simpson, M., Adily, A., Grant, L., & Butler, T. (2019). Spatial density and infectious and communicable diseases: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 9(7), e026806. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026806

The Council of State Governments Justice Center (2015). Reducing recidivism and improving other outcomes for young adults in the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems. https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Transitional-Age-Brief.pdf

UCLA Law COVID Behind bars data project (2020). https://uclacovidbehindbars.org/

Uggen, C., & Wakefield, S. (2008). Young adults reentering the community from the criminal justice system: the challenge of becoming an adult. On your own without a net (pp. 114–144). University of Chicago Press

Van Duin, L., de Vries Robbé, M., Marhe, R., Bevaart, F., Zijlmans, J., Luijks, M. J. A. … Popma, A. (2021). Criminal history and adverse childhood experiences in relation to recidivism and social functioning in multi-problem young adults. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(5), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854820975455

Viglione, J., Alward, L. M., Lockwood, A., & Bryson, S. (2020). Adaptations to COVID-19 in community corrections agencies across the United States. Victims & Offenders, 15(7–8), 1277–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2020.1818153

White, M. D., Saunders, J., Fisher, C., & Mellow, J. (2008). Exploring inmate reentry in a local jail setting. Crime & Delinquency, 58(1), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128708327033

Williams, T., Weiser, B., & Rashbaum, W. K. (2020, December 1). ‘Jails are petri dishes’: Inmates freed as the virus spreads behind bars. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/us/coronavirus-prisons-jails.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abrams, L.S., Reed, T.A., Bondoc, C. et al. “It was there when I came home”: young adults and jail reentry in the context of COVID-19. Am J Crim Just 48, 767–785 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-022-09683-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-022-09683-8