Why a Maritime Forecast Is So Beloved in the United Kingdom

This weather report has been making waves for 150 years.

For the penultimate song on their 1994 album Parklife, Blur chose the swirling, meditative epic, “This Is a Low.” The song envisions a five-minute trip around the British Isles as an area of low pressure hits.

“Up the Tyne, Forth, and Cromarty,” sings the lead singer Damon Albarn, “there’s a low in the high Forties.” The song’s litany of playful-sounding place names, including the improbable “Biscay” and “Dogger,” may seem obscure to listeners abroad, but to a British audience, they resonate.

The song’s lyrics were inspired by the Shipping Forecast, a weather report that is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on behalf of the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. Sailors working around the coasts of Britain and Ireland, recipients of the wrath of the North Atlantic and North Sea, are the ostensible beneficiaries of the forecast.

But, for listeners who tune in while tucked in bed rather than sailing the high seas, the reassuring sound—a simple, steady listing of conditions in the seas around the British Isles, broken down into 31 “sea areas,” most of which are named after nearby geographical features—is something more akin to the beating pulse of the United Kingdom, as familiar as the national anthem or the solemn chimes of Big Ben.

“We always found the shipping forecast soothing,” Blur’s bassist Alex James explained to Select in 1995. “We used to listen to it to remind us of home.”

Broadcast four times a day (00:48, 05:20, 12:01 and 17:54 GMT), the forecast begins with gale warnings, if necessary, and a general synopsis before moving clockwise around the map of the islands, always starting in “Viking,” an area of open sea between Shetland and Norway. In around 350 words, each of the 31 areas’ forecasts is read out: wind, sea state, weather, and visibility. Where conditions in neighboring areas are similar, those areas may be combined into a single forecast (as in: “Viking, North Utsire, South Utsire: Variable, becoming southeasterly 3 or 4, occasionally 5 later. Moderate. Fair. Good.”)

There are slight variations between broadcasts. The first and last of the day include reports from coastal stations. Due to length restrictions, the most distant sea area, Trafalgar, which extends from southwest Portugal to northwest Africa, is usually only included in the slightly longer 00:48 broadcast. This post-midnight transmission is preceded by a piece of music called “Sailing By,” a swooning tune that lets sailors know they’ve found the right station.

So evocative is this economical language—which occasionally slips into the philosophical (“Low Rockall 1000, moving southeast and losing its identity by 0600 tomorrow”) and the plaintive (“Good, occasionally poor”)—that the members of Blur are just some of many artists to have cited the Shipping Forecast as inspiration.

It has been referenced by Radiohead (the song “In Limbo”) and sampled by The Prodigy (the song “Weather Experience”). A snippet was included in the 2012 Olympic Opening Ceremony and the words “Fisher” and “German Bight” (names of sea areas) anchor a memorable scene in the Ken Loach movie Kes. The late Irish poet Seamus Heaney, who wrote a poem titled “The Shipping Forecast,” suggested that his craft was “stirred by the beautiful sprung rhythms of the old BBC weather forecast.”

Few could point out all the sea areas on a map, let alone claim to have visited many. (One major exception is the author Charlie Connelly who wrote a book, Attention All Shipping, about his year-long journey to each of them.) And yet the names are familiar. When I visited Fair Isle for the first time this year, I felt a quiet thrill at having completed what I consider the “set” of Fair Isle, Faeroes, and Southeast Iceland. Sure enough, the island’s gift shop was filled with such Shipping Forecast memorabilia as tea towels and greeting cards.

The Shipping Forecast doesn’t describe anything about these 31 places, and yet the sound of each named sea area is like the ringing of a bell. It reminds British citizens that they are part of an island nation.

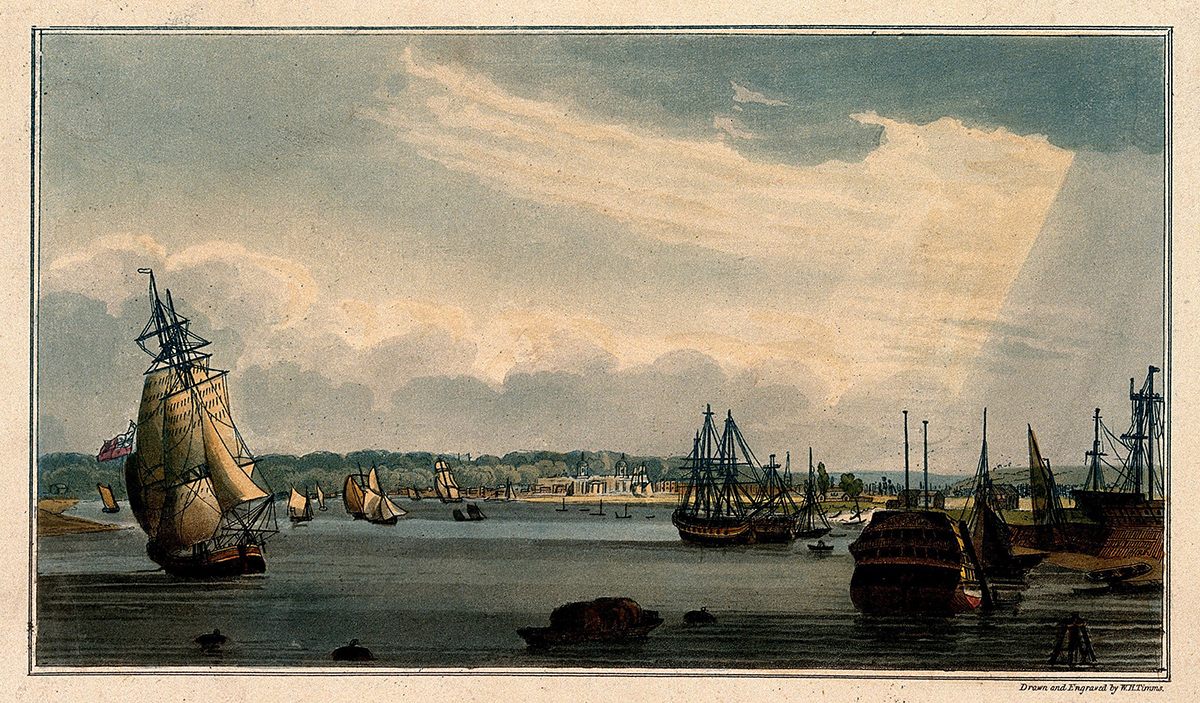

“As a former seafaring nation that has turned its back on the sea,” wrote Nic Compton in the introduction to The Shipping Forecast: A Miscellany, which was released in 2016, “it awakens our DNA and reminds us of our not so distant (and not always proud) maritime heritage.”

This year, the Shipping Forecast celebrated 150 years of uninterrupted service, and it’s hard to ignore that the nation is in the grips of a nationalistic wave as the post-Brexit nation grapples with its position in the world.

As the anniversary prompted reflection on the Shipping Forecast’s legacy, some have wondered if its bewildering popularity betrays the U.K.’s nostalgia for the past, for a more glorious time when Britannia ruled the waves and the country was more stubbornly defined as an island. It was, after all, just a year ago that an isolationist attitude and demand for “control” of the nation’s borders culminated in the U.K voting to withdraw from the European Union.

Getting “our country back” was the rallying cry of the “Vote Leave” campaign and fishermen—people who actually benefit from the Shipping Forecast—were heavily targeted by campaigners exploiting their grievances with European Union-imposed fishing quotas. An article by Frank Jacobs, author of Strange Maps: An Atlas of Cartographic Curiosities, describes the Shipping Forecast as “a declaration of geopolitical detachment expertly disguised as a weather bulletin. Splendid isolation masquerading as shifting isobars.”

Indeed, the Royal Navy was at the height of its powers when Vice Admiral Robert FitzRoy first conceived of the forecast. In 1854, FitzRoy had been appointed head of the organization that was the predecessor to the Meteorological Office, which was set up under the Board of Trade. Five years later, during a severe storm, the Royal Charter, a steam clipper, sank in the Irish Sea with the loss of more than 450 lives. FitzRoy felt that he could have predicted that storm and persuaded the Board of Trade to allow him to start a warning service, which he established in 1861.

Via electric telegraph, observations came into the Met Office from the coastal stations FitzRoy had set up. The warnings, again delivered by telegraph, then went out to ports which, through a system of cones and drums, let ships know that a storm was coming and from which direction. A few months later, in August 1861, thinking that people on land might also be interested in impending weather conditions, he published his first “forecast” (a term he coined) in the Times newspaper. It is thought to be the first public weather forecast in the world.

FitzRoy’s forecasts were not always accurate, but he continued working to improve them. Finally, exhausted by his efforts and troubled by depression, from which he’d long suffered, he slit his own throat in April 1865.

After his death, the Board of Trade ceased issuing forecasts until public pressure forced their return in August 1867. Besides some grumbling from fishermen aggrieved over a day’s lost catch due to a mistaken signal, sailors and the public at large were generally supportive of the forecasts. The broadcast moved onto radio when the BBC was formed in the 1920s and FitzRoy was finally honored when sea area Finisterre was renamed FitzRoy in 2002.

Perhaps the Shipping Forecast does prompt dreams of Britain’s past, but maybe it’s so loved simply because it prompts actual dreams, too. That’s the thinking behind the Shipping Forecast-inspired “Sleep Story” by the meditation app Calm.com. The app’s Sleep Stories are exactly what they sound like: narrative sleep aids. One such tale adapts the Shipping Forecast into a kind of bedtime story with the specific aim of lulling its listeners to sleep.

The story is narrated by Peter Jefferson, who read the Shipping Forecast from 1969 to 2009, and is the author of And Now The Shipping Forecast. “Several times over the years people would say that listening to the Shipping Forecast had a soporific effect on them,” Jefferson says. “I suppose it can have that effect at the end of a long day—listening to a familiar voice relating familiar names and phrases coming over the airways, while you are relaxed and tucked up in bed heading hopefully towards sleep.”

Most of the text for the Sleep Story was the final forecast Jefferson read on air, “with one or two tweaks to calm down one or two of the more rumbustious sea areas.”

Those edits highlight the contradiction of the Shipping Forecast—that what Calm’s founder Alex Tew calls a “national lullaby” can often tell of quite horrific conditions. Rarely are such conditions more dire than they were on October 15, 2017, when, as Storm Ophelia approached the British Isles, listeners heard the words—read, as always, in a calm cadence—“violent storm 11 for a time, occasionally hurricane force 12 in Fitzroy, Sole, Fastnet, and Shannon.”

Some Twitter users described it as “exciting” but there was also a sense of empathy for those out on the seas, still working to bring the country much of its resources. And, for that moment at least, perhaps a few minutes’-long radio broadcast drew a fractured region closer together.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook