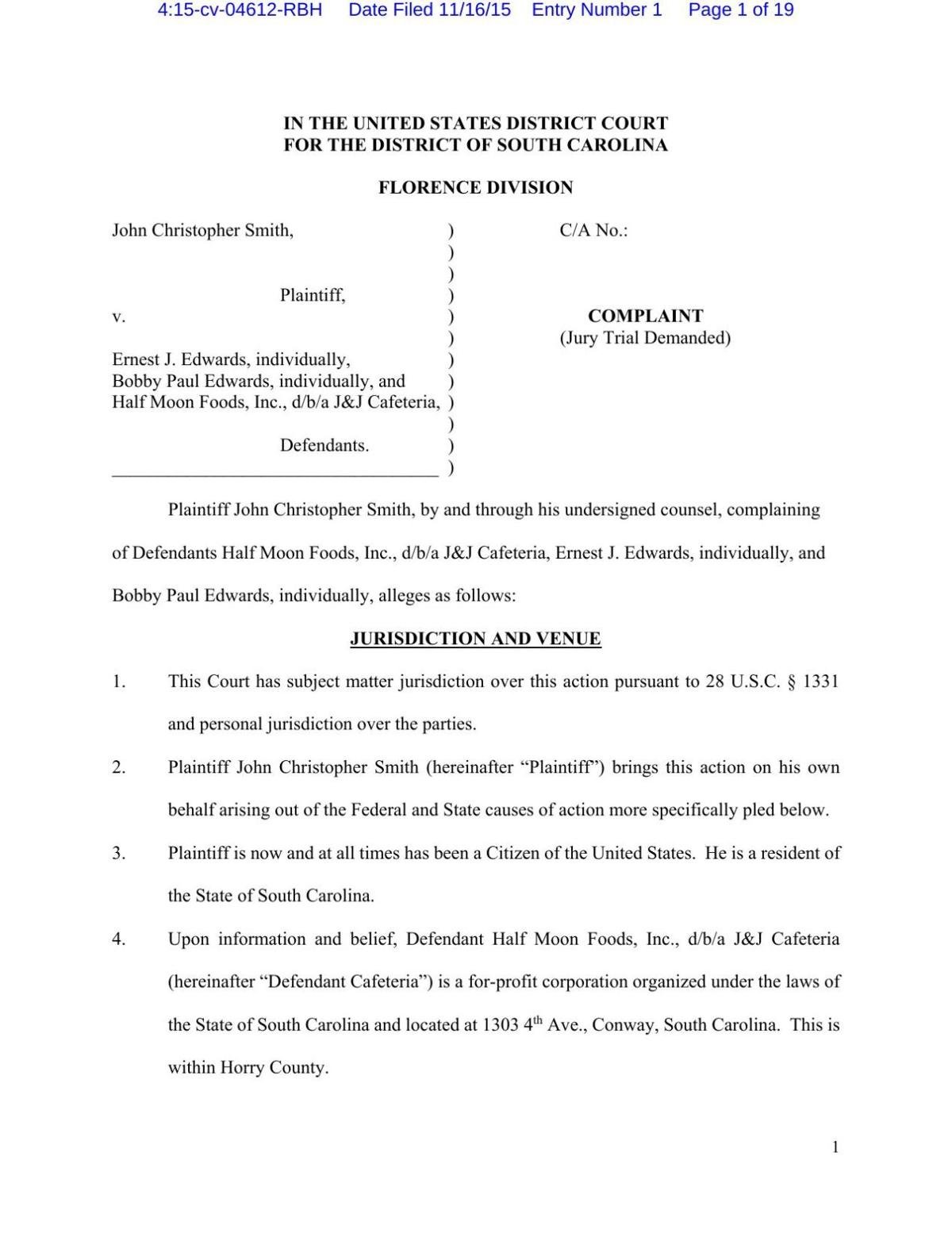

Christopher Smith was beaten, whipped, called racial slurs and forced to work 100 hours a week or more without pay at J&J Cafeteria in Conway. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

CONWAY — In the cold formality of a federal courtroom, beneath a soft velour tracksuit, Christopher Smith bore the scars of whippings, beatings and burns.

Five years had passed since the intellectually disabled man’s rescue. Headaches and post-traumatic stress disorder plagued him. His feet and back throbbed from the hours, 100 or more a week, that Bobby Paul Edwards forced him to work without pay.

Edwards was manager of J&J Cafeteria, a diner-style restaurant in downtown Conway, the small-town seat of coastal Horry County. Given the restaurant operated within eyesight of the county courthouse, it filled with all manner of people charged with protecting the citizenry. Police and prosecutors were among those who strolled over to feast on the buffet Chris kept filled with fried chicken, okra and mac 'n' cheese.

How his cries for help — echoing from the walk-in cooler, the kitchen, an office beside the dining room — went unheeded for so long remains a great question to many, none more than Chris.

Every day, he feared that Edwards might kill him.

Every night, he prayed for God to save him.

Chris Smith closes his eyes while resting at a home he shares with family members. For six years, Chris feared that his boss, Bobby Paul Edwards, might kill him. Every night, he prayed for God to save him. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

Now, under the watchful eye of a federal judge, Chris stood behind the prosecutor’s table. He and Clarissa Whaley, a victim advocate with the U.S. Attorney’s Office, had prepared a statement for this moment when Edwards would, at long last, be sentenced for the crime of forced labor.

Chris was 41 years old. He was not alone, not anymore. His mother and sister had come with him. His attorneys sat at a table near him. And Whaley read his statement about the torment.

For almost six years, Edwards had built an insidious trap of financial power, isolation and violence that human traffickers often use to control their victims. Sometimes, the scourge festers in the nation's murky shadows. Other times, right in plain sight.

Wearing an orange prison jumpsuit, Edwards stared at the carpet as Chris said in his statement:

“Today, I feel free.”

•••

It is hard to picture how something that looked so much like slavery happened at all in the 21st century, much less beneath the noses of so many. It is even harder given the fact that these two men’s families — one Black, one White — had been intertwined for decades.

MAN HELD AT CONWAY RESTAURANT: Although Myrtle Beach gets more attention for human trafficking reports, the county seat of Conway is where Chris Smith was held in slave-like conditions for almost six years. (SOURCE: ESRI)

Chris’ grandmother, mother, uncles and various cousins had all worked at J&J. They cooked up mounds of Southern food in its kitchen, which had a big cutout window in the wall that let banter from the dining room flow in — and noise from the kitchen flow out.

A low-slung building with a metal roof painted bright red, the place had an old-timey feel with Coca-Cola signs, a lunch counter and a framed American flag on one wall. A replica of a 1950s Chevy Bel Air hung over the buffet.

Its long front windows stretched down a busy street. People who walked or drove by spotted friends inside, then slipped in to catch up on gossip and news. Decades of farmers, families and downtown professionals had dined at its tan tables and booths.

Three generations of Edwards men had owned J&J and built it into a local staple. Jeff Edwards opened the restaurant in the mid-1950s, around the time the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racially segregated schools unconstitutional.

Chris was born in 1978, eight years after most school districts in South Carolina finally, under a court order, desegregated. By the time he was 12, he walked to the restaurant after school and washed dishes, earning $30 a day under the table.

As he did, school held less appeal. His freshman year, a psychologist classified him as educable mentally disabled. In her report, she wrote that he struggled with traditional classroom lessons and should focus on learning socialization and basic job skills.

Chris Smith at age 12, around when he began working at J&J Cafeteria in Conway as a part-time dishwasher. Provided

Chris dropped out of school and began working at J&J full time, moving up from dishwasher to cook. Eventually, he prepared all dishes for the restaurant’s buffet, frying chicken and okra, whipping up mashed potatoes, simmering gravy and rice.

During the years Jeff Edwards and then Joe Edwards owned the restaurant, Chris felt well-treated. But then Jeff died in 2005, followed by Joe four years later. Bobby Edwards’ older brother owned the restaurant next.

Bobby took over its day-to-day operations.

By then, Chris and an uncle were the last of their family still working at J&J. When his uncle suspected he wasn’t getting paid properly, he quit — and urged Chris to leave with him.

Chris hesitated. Although he was a grown man of 31, he didn’t drive. He could be too trusting. J&J offered him familiar tasks with familiar people. He had worked there since he was a child.

Sure, Bobby Edwards was a hothead. But he didn’t seem too bad.

At the same time, J&J underwent renovations — complete with a new “apartment” connected to the back. Edwards told Chris to move in, even though the space had no kitchen. Or washing machine. Or windows.

But if Chris did, he wouldn’t have to bother people to drive him to work or risk being late when he got distracted.

He would be right there, all the time.

Conway police officers had just arrested Chris on a minor drug charge. Edwards later told people that he got Chris out of jail.

Chris owed him.

•••

Conway sits inland 15 miles — and cultural light years — away from Myrtle Beach, a city of towering ocean-front hotels, tourist shops and golf courses that attract millions of visitors a year. But the power of officialdom in Horry County lies in Conway, a growing river town that is home to about 24,000 people.

J&J operated in the heart of it.

J&J Cafeteria, seen in the bottom left, sits a quick walk from the Horry County Courthouse, the red brick building with a cupola in the upper left. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

When Chris ventured out the restaurant’s side door, there before him, down a gentle slope, rose a century-old red brick structure fronted by four white columns: the Horry County Courthouse. Behind it stood the county's justice building, home to the Solicitor’s Office, where Edwards’ aunt was office manager.

Lawyer’s offices ringed the complex.

Such proximity drew deputies, prosecutors and judges to J&J. Officers from the Conway Police Department, not a mile in the other direction, flocked there, too. They lingered at the lunch counter and clustered around a favorite table in the back near Edwards’ office.

Sometimes, he sat with them.

Other times, police came in through the back door and hung out with Edwards in his office, which had a one-way mirror looking onto the dining room. He boasted that he gave the cops loans under the table. He liked to flash a wad of cash and brag about knowing people in high places.

So when he told Chris that he had the police in his pocket, it sure seemed true.

•••

When Chris moved into the apartment behind J&J, Edwards stopped paying him directly. He claimed he was taking out money for rent and putting the rest into a bank account for Chris.

He only doled out money for Chris to buy hygiene products and snacks like Little Debbies to eat when he wasn’t working. Every few weeks, Edwards handed him cash for a haircut.

Chris Smith walks down his street toward the local bus station where he will catch a bus to the Freshwater Fish Co. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

He also began making Chris work more — morning shifts and night shifts, even when Chris was sick. Chris felt like he never got a day off anymore. When he was tired, or moved too slowly, or didn’t keep the buffet full during the busiest rushes, Edwards berated him. He called him lazy, stupid, a sorry bastard.

During one tirade, Edwards called Chris the n-word. It stung in a particular way. Conway had its racists, to be sure, but no White person had ever called Chris that before.

Chris kept quiet. He tried to work harder. Edwards was the boss, and Chris needed the job.

Then came a Sunday, an especially busy one when Chris struggled to keep the buffet full. As Edwards unleashed a torrent of profanity, he steered Chris into his office on the other side of a wall from the dining room.

Then, he hit him.

Chris stood there stunned. His mind scattered. His eyes darted around in search of something to fight back with. But he saw nothing.

•••

Chris’ mother, Alma, hoped that living right behind the restaurant made life easier for him. He had a place to stay and a steady job.

Given Chris didn’t have a cellphone, she had to call the restaurant’s line to talk to him. It began to seem like every time she called, Edwards told her Chris was occupied. Then he’d hang up. Sometimes, she would call back but the line was busy. Other times, whoever answered put her on hold and did not return.

Alma, who also didn’t drive, moved an hour away to Pawleys Island to care for a young grandson, who had cancer. When she got a ride to the restaurant to visit Chris, Edwards shooed her away, saying Chris did not have time to lollygag. When Alma sent her sister, she got the same message.

Frustrated, the two women went together once and, this time, walked behind the restaurant. They waited for Chris to take out the trash so they could talk to him alone. But Edwards followed him out.

When Alma heard that Edwards hit her son on the hand with a spoon, she got a ride to the restaurant the next day. Chris denied it happened, even though his fingers looked swollen.

Alma urged him to find another job, but Chris clammed up. It felt like he didn’t want to talk to her.

She had no idea how deeply Chris missed her, or how much he longed to leave J&J. But even more, he feared for his family’s safety. Edwards had threatened to harm them if he spoke a word.

And by then, Chris was not sure what Bobby Edwards was capable of.

•••

Around the time Edwards became manager, Melanie Heath applied for a waitressing job at J&J.

It felt like a family place.

She met Edwards’ mother, father, wife and sons when they came around or helped out working. She learned Edwards' older brother owned the restaurant; his younger brother was preparing to become a Conway police officer.

When Heath switched from waitress to cook, she befriended Chris during the hours they spent together in the kitchen. In fact, it seemed like he was always there.

She quickly realized that he worked seven days a week, from 6 a.m. until almost midnight, except on Sundays when the restaurant closed at 2 in the afternoon. He even lived in a room attached to the back of the restaurant.

Mostly, Heath noticed how terribly Edwards treated people. It was like he had this internal switch that transformed him from jokester to devil. She cringed at how he spoke to his wife. She watched aghast as he dressed down the waitresses and cooks.

When he screamed at Heath, she cried.

Bobby Paul Edwards. File/Provided

In the worst rages, he always targeted Chris. He would scold him like a child, then drag him to the back of the restaurant, beyond people’s eyesight. Other times, he cursed at Chris in the kitchen right by the cutout window to the dining room. Customers could hear it all.

Sometimes people looked uncomfortable, their eyes darting toward the kitchen or office. A few asked who was screaming back there. Others quietly left.

But nobody said anything more. Or did anything more.

Edwards’ family began to come in less. Heath went home in tears more. Chris was such a gentle soul, and he worked so hard. It was the worst job she’d ever had. But she needed it.

A single mom with two daughters, she feared becoming homeless. Winter approached, and the tourists in Myrtle Beach were gone, the restaurant jobs scarce.

One day, Edwards arrived in an especially vile mood and began spewing profanity. As usual, Chris stayed quiet, even as Edwards hurled the n-word at him. Then Edwards drew his hand back and slapped Chris.

Heath stood there shocked.

When Edwards stormed away, she hurried to Chris. Under her breath, she asked if he was OK.

“Don’t you worry about me,” he said.

It went on. When Edwards pulled Chris into the office or the walk-in cooler, she heard slapping sounds. At night, Chris’ words echoed through her thoughts: “Don’t cry. It will just make him mad.” She wondered where his family was.

When she approached Chris about going to the police, he begged her not to. He told her that he had been arrested on a drug charge once and Edwards threatened to have him thrown back into jail for it.

Heath wasn’t sure what to do.

Heading toward the holidays, during an especially busy shift, she was grilling steaks while Chris fried chicken. Edwards grew enraged at them both for not cooking fast enough.

He grabbed a pair of metal tongs and dipped them in the spitting-hot fryer grease. Then he pressed them across the back of Chris’ neck.

Chris winced.

Edwards smirked at Heath, like he’d just been joking around.

The next morning, a long blister, thick as her finger, bubbled up on Chris’ neck. The waitresses pooled their money, then went to Dollar General to buy Neosporin, bandages and medical tape to care for his wound.

Heath could not take it anymore.

When she landed a job at Walmart, she left.

Melanie Heath talks with Sharawn "Bubba” Chestnut while making sweet tea at Big Mike’s Soul Food in Myrtle Beach. Heath loves the job, especially compared to her time working at J&J Cafeteria, where she saw Bobby Paul Edwards burn Chris Smith on the neck. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

•••

In mid-2013, a few years after Melanie Heath left J&J, a careerlong waitress applied for a job. Chelle Duncan wanted to work close to home, and several friends said J&J was the best place in Conway to make money.

At first, she worked mostly at night. Then she picked up some morning shifts.

Chris was always there. She tried not to notice that his clothes looked worn and ill-fitting. He walked with his head down. Some people said he was “slow." But he smiled at her, and he cooked some tasty rutabagas, her favorite.

Duncan was mostly distracted by her patronizing new boss. Everyone got nervous when Edwards came in — none more than Chris.

One day when the buffet ran out of fried chicken, Duncan walked in on Edwards screaming at Chris right in his face, one hand raised. When Edwards saw her, he lowered it.

On a Sunday after that, Edwards spent a morning cussing at the employees, even though his mother was in the restaurant and it was packed with customers. Duncan was serving her tables in the dining room when she heard Edwards unleash a profane tirade in the kitchen.

His mother pleaded, “No, Bobby, don’t.”

Duncan heard what sounded like a whip cracking.

She peered into the kitchen and saw Edwards steering Chris to the back door. Edwards’ mother was crying.

Shaken, Duncan joined three other waitresses as they rolled silverware when the lunch rush settled. Had they heard the commotion?

One said she had heard it too and tried to go into the kitchen. Edwards’ mother had pushed her back out, she said, but she still caught a glimpse of Edwards slipping off his belt.

Duncan felt sick to her stomach. She remembered the whipping sound.

The women debated what they could do. One said that people had tried calling the police, but they never came. Another had heard that when the police did come, they talked to Chris in front of Edwards, so he denied the abuse. (A Conway police spokeswoman later said the agency had no records of reports or calls about the abuse during this time.)

But the waitresses also were scared of Edwards. One said her husband was on disability and she couldn’t afford to lose her job. What could they do?

•••

Finally, in the summer of 2014, five years after the abuse began, a woman who used to work at J&J called the state Department of Social Services.

She wanted to report a vulnerable adult being beaten at J&J.

The woman, 51-year-old Geneane Caines, had known the Edwards family for 32 years. She had worked on and off at J&J, back before Bobby Edwards ran it. He could be a loudmouth, but she considered his parents to be good people.

So she had recommended the place to her daughter-in-law, who took a waitressing job there.

The younger woman soon came home in tears. She told Caines about the racial slurs, the screaming and the beatings Chris endured.

Caines had worked for Horry County Disabilities and Special Needs, so she knew how the system worked. Which is why she called the local DSS office that day. (A spokesperson later said the agency has no record of this call, but at the time county offices did not document reports they didn't pursue.)

She heard nothing back. Weeks passed. Months passed. Her daughter-in-law came home increasingly distraught.

As fall arrived, the abuse escalated.

On a Monday, Edwards hit Chris in the kitchen with a metal spatula.

On Tuesday, he pulled Chris into the office and beat him with a belt.

On Wednesday, he shoved Chris into the walk-in cooler and hit him on the head with a metal pot as Chris screamed for help.

On Thursday, Caines’ daughter-in-law came to her again, crying: “He’s gonna kill him.”

Caines counted four months since she called DSS.

This time, she dialed Gov. Nikki Haley’s office.

Chris Smith's life after his rescue

Chris Smith was beaten, whipped, called racial slurs and forced to work 100 hours a week or more without pay at J&J Cafeteria in Conway. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff.

CONTINUED BELOW

•••

The next day, Sherry Johnson opened an email from her boss, the director of Horry County DSS. It contained a message forwarded from the governor’s Office of Constituent Services.

A concerned citizen had reported a vulnerable adult being abused by his employer at J&J. Would Johnson look into it?

Johnson gathered a caseworker, then stopped at the Conway Police Department to find two officers who could escort them. They headed to the restaurant.

Chris was cooking when a waitress told him that someone wanted to talk to him. Normally, Edwards stepped in when anyone came to see Chris.

This time, Edwards wasn’t there.

Chris spotted an officer standing at the counter. Was he there to arrest him, like Edwards had threatened? Another officer joined the man, and they led Chris outside to the parking lot. Chris saw two women.

Johnson introduced herself and explained why they were there. She asked Chris if someone had whipped him with a belt.

Chris looked first at the officers. He hesitated. Then he looked at the women.

“Yes.”

Who beat you?

The “bossman,” he said. Bobby Edwards.

With a fist? “Yes.”

On the head with a pan? “Yes.”

She asked to see the back of Chris’ neck. He turned around to reveal a thick scar from the grease burn, plus other scars on his back from a belt. Johnson spotted a knot on his head, too. Edwards had beaten him in the walk-in cooler that morning.

She asked Chris if he was afraid of Edwards.

“Yes.” But he had no money or anywhere to go.

The women assured him: If he wanted to leave, someone had agreed to take him in until he got onto his feet.

Chris glanced down at his black apron, doused in flour.

He took it off.

Johnson told the officers they were taking Chris into adult protective services custody.

Another Conway officer, who was lingering in the parking lot, had been listening to the exchange. He chimed in, “Who is going to fry the chicken?” Then he drove away in his cruiser.

Chris and the two officers walked around to the back of the building where Chris lived. When the women pulled around to a small parking lot, Chris was standing there with the officers.

And Bobby Edwards. He asked what was going on.

While Johnson explained, she sent Chris inside to gather his personal items. He emerged with two small boxes.

Edwards asked where they were going.

He asked Chris what he needed.

He insisted Chris had been to his house on Christmas: “I been Santa Claus to him.”

Chris did not respond. As the tone escalated, Johnson sensed him shutting down. She told him to get into their car.

Edwards hollered at Chris: “I love you!”

•••

When the trio arrived at Geneane Caines’ house in Aynor, she and her family stood outside waiting for them. Chris got out of the car and saw her daughter-in-law, the waitress Jenny Powell. He couldn’t believe it.

Powell ran over and hugged him.

“You’re safe now,” she said.

Chris followed Caines inside to the family’s spare bedroom, one with a TV in it.

She quickly realized the conditions Chris had been living in. When she lifted his clothes from a box, roaches scattered. She washed the garments in hot water with detergent and vinegar, then realized that he did not have underwear or socks.

Her heart ached for the man, and she promised: He would never have to return to J&J.

Evening approached, and everyone was hungry. They headed to Santino’s Pizza, where Chris began to worry that he no longer had a job. He feared winding up on the streets, an anxiety Edwards had used to control him for years.

The owner promised to help. Chris could work for him 40 hours a week, not 100 or more, and get paid.

All weekend, Chris repeated how glad he was to be away from Edwards.

He was also terrified. So many times, Edwards had threatened that if Chris tried to leave he would get him arrested for drugs.

Caines tried to reassure him.

But Chris knew Bobby Edwards better than anyone.

Chris Smith relaxes with his mother, Alma, in the kitchen, moments before he heads to the local bus station on his way to work at Freshwater Fish Co. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

•••

First thing Monday morning, Edwards called the Conway Police Department. He reported that Chris had drugs in his room. An officer arrived and gathered a mostly empty baggie with what appeared to be marijuana residue and a single bud.

But to Police Chief Reginald Gosnell, it seemed a convenient way for Edwards to deflect attention from the violence. He would not pursue charges.

Gosnell also worried about Edwards’ younger brother, who was on his force. The chief considered him to be a top-notch officer. But the public perception wouldn’t be good.

At DSS, Johnson firmly agreed. An outside agency needed to be involved.

She called the State Law Enforcement Division.

•••

Around lunchtime, Caines heard a knock on her door. Outside waited Russell Causey, a SLED agent who investigated crimes against vulnerable adults.

She introduced him to Chris, and the two men sat at her kitchen table.

For the first time, Chris opened up to a law enforcement officer. He described the beatings, the forced work without pay, the threats and fear, the isolation. He also wrote a two-page statement.

The SLED agent also spoke to Caines' daughter-in-law and took her statement. She wrote that while waitressing, she heard Edwards tell Chris “that he would stomp his throat out, break his jaw, beat him where no one could recognize him.”

Photos: Chris Smith's life after he was rescued

Chris Smith was beaten, whipped, called racial slurs and forced to work 100 hours a week or more without pay at J&J Cafeteria in Conway.

Another waitress who had come with her also gave a statement. Others would come forward, too.

The SLED agent left around 5 p.m. He had been there for more than four hours.

In his report, he described Chris’ speech and movements as “extremely slow.” He contacted Johnson at DSS to be sure Chris would be evaluated for intellectual disabilities.

•••

A month after Chris was rescued, he received a phone call from a different SLED agent. Edwards was going to be arrested.

Hope filled Chris. Edwards would pay for what he had done.

Yet, although the warrant said Edwards had repeatedly beaten and tortured Chris, the man faced only one charge of second-degree assault and battery — a misdemeanor, albeit one with a maximum three-year sentence.

Chris, his family, Caines and the waitresses all thought the same thing: That’s all?

It was late 2014, and most South Carolina prosecutors, including the one who brought the assault charge, were unfamiliar with a far more powerful tool at their disposal: the state’s relatively new human trafficking law. A first offense carried a maximum 15-year sentence and a felony record.

The statute had gone into effect in December 2012, less than two years earlier, but not a single case had been brought yet with it. Law enforcement and prosecutors had received little to no training about its provisions.

So they still turned to the usual hodgepodge of charges — ones like assault.

Edwards was booked into jail. A few hours later, he was released on a $10,000 bond.

At Freshwater Fish Co., Chris Smith cuts and cleans fish before putting them in the store's glass display counter. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

•••

Two weeks later, Chris’ caseworker drove him to a Myrtle Beach psychologist’s office.

Over the two-hour session, Chris described the abuse and frequent flashbacks of Edwards beating him. It took him a long time to fall asleep at night, and sometimes he woke up at 3 a.m. and couldn’t go back to sleep. He startled easily.

Chris said he was working at Santino’s as a cook. But Edwards' family members came into the restaurant, and he heard Edwards was living near him. Chris had moved into a two-bedroom trailer and lived alone. He feared Edwards would find it and try to kill him — or get someone else to do it — now that he was out of jail.

The psychologist diagnosed Chris with PTSD and recommended therapy. He also placed Chris’ IQ within the “mild mental retardation” range and his intellectual sophistication at roughly that of a 9- or 10-year-old.

DSS considered Chris to be a vulnerable adult in need of special assistance.

But criminal investigators did not, based on the information they had at the time.

It remained an assault case.

•••

Charleston lawyer Mullins McLeod heard about the case from a fellow attorney who represented Chris on a minor drug charge. As McLeod learned more, he couldn’t believe it.

By then it was autumn, nearing the one-year anniversary of Chris’ rescue. The assault charge sat there, but nothing more.

To McLeod, the crime appeared far more egregious than an assault. A third-generation attorney, he had just won two of the state’s largest wrongful death verdicts and had begun to represent people whose loved ones were killed by a white supremacist in the recent Emanuel AME Church massacre.

He strongly believed the law provides tools to right injustices.

But which tool could do that for Chris?

McLeod handed the question to Michael Cooper, a new attorney at his firm who dove into the statutes — and came up with an idea.

More than a century after the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery, the federal human trafficking statute was amended in 2000 with a new section called “forced labor.” Anyone who obtains labor by threats, force or serious harm could face up to 20 years in prison. Aggravating factors could drive that up to life in prison.

Cooper went to McLeod: This was a human trafficking case.

Unlike state authorities, the lawyers threw a spate of allegations at Edwards. In November 2015, they filed a 14-count federal civil lawsuit against Bobby Edwards, his older brother Ernest Edwards and the restaurant’s registered corporation, Half Moon Foods Inc.

This wasn’t only about an employer assaulting a worker.

It was about a White man terrorizing a Black man, whipping him, beating him, forcing him to work ungodly hours with no pay and no days off.

Count one read “SLAVERY.”

With that, the story went national.

Four days after the private attorneys filed the lawsuit, prosecutors forwarded Chris’ case file to the FBI.

Big Mike’s Soul Food restaurant in Myrtle Beach displays a poster for the National Human Trafficking Hotline. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

•••

Labor trafficking involves compelling someone’s work by force, fraud or coercion. Jared Fishman, a federal civil rights prosecutor in Washington, D.C., heard about Chris’ ordeal and thought: “That’s exactly what is happening in this case.”

With the feds involved, a cadre of people suddenly surrounded Chris. At first, he didn’t know what to make of them. He still harbored a strong distrust of law enforcement.

FBI agent Torrance Bassard began by investing hours into building a relationship with Chris. They often drove around town while Bassard asked Chris about himself.

In turn, Chris explained that Edwards would drive him around, too. He would show Chris his house, his pool, his car. “This right here,” Chris quoted him saying, “I bought it with your money.”

Bassard introduced Chris to others on his team.

Chris Smith (left) catches up with Clarissa Whaley, a federal victim advocate, before beginning work at Freshwater Fish Co. in Conway. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

Over chips, fruit and sweet tea in the FBI’s Myrtle Beach field office, Chris became comfortable with the group. He especially liked Clarissa Whaley, a federal victim advocate with a gentle voice and deep faith. She helped Chris put words to things he felt. Hopeless. Isolated. Afraid.

She also helped him realize that he was worthy of being protected. Part of that was helping him see his strengths. When the group asked Chris how much Edwards owed him in back pay, he added up the hours, the days, the weeks and years.

“Chris,” Whaley said, “you’re good with numbers.”

She also asked Chris about his dreams. What did he want out of his life now?

He described opening his own restaurant, one that would serve soul food and seafood. Customers would be kind, everyone welcome (except for racists). And he would hire the waitresses from J&J who comforted and bandaged him.

Eventually, Chris shared his fried chicken recipe with the group.

He also provided the factual details they needed.

In October 2017, three years almost to the day after Chris was rescued, the federal court unsealed an indictment charging Edwards with one count of forced labor.

This was a felony, carrying a maximum of 20 years in prison.

Around Conway, people who knew Edwards and his family were shocked. Some took to social media to defend him. But as locals debated his character on Facebook, Edwards’ life was imploding.

His wife filed for divorce. He got arrested twice for shoplifting. Then he got charged with first-degree burglary, driving under the influence and marijuana possession. An officer responding to an alarm found Edwards at his soon-to-be ex-wife’s house with cuts on his fingers. A window was smashed in, the screen yanked out.

Edwards told the officer that within the past few hours, he had consumed a couple of Twisted Teas, smoked marijuana, and taken Adderall and Xanax.

Eight months after the forced labor charge was filed, Edwards pleaded guilty and reported to prison. He was 53 years old.

With Edwards locked up, Chris felt safer. He could breathe and look ahead.

As the summer sweltered, he met with Whaley and a federal prosecutor handling his case. He asked them for help writing a statement they could read at Edwards’ sentencing hearing.

Edwards had silenced him for so long.

Now, Chris wanted to be heard.

•••

In November 2019, Whaley arranged for a car service to drive Chris and his family to Edwards' sentencing hearing an hour away in Florence.

By then, Chris had moved in with his mother and younger sister, Lasonya Barr, who lived in Virginia during the years of abuse. When she returned to Conway with her two young children, she found Chris living in squalor with a man who seemed suspiciously interested in any money Chris was due.

She chased the man off. And took Chris in.

The evening before Edwards would appear in court, she arrived with Chris and their mother in Florence. They checked into a hotel, ordered Domino’s and watched a movie before falling asleep.

Then they emerged into a chilly morning. The courtroom was even more frigid. Barr felt like she had entered a morgue. Shivering on the edge of her seat, she wondered how Chris would react to seeing Edwards. Would he break down in tears? Flip out in anger?

Instead, he cracked a joke.

When Edwards shuffled in wearing a prison jumpsuit, Chris whispered that the man looked rough. Prison must not be good for him. He and Barr chuckled quietly.

Once the attorneys debated restitution, it was Edwards’ turn to address District Judge Bryan Harwell. He apologized to Chris, his employees and his family.

“I let a lot of people down, and I'm sorry for that,” Edwards said.

But he insisted that he was a different person now. His attorney, Robert E. Lee, requested Edwards be housed at a prison that offered drug treatment.

Then it was Chris’ moment.

He stood behind the prosecutor’s table. Whaley rose to stand on one side of him. Fishman, the federal civil rights attorney, stood on the other. Chris’ mother and sister sat behind him, forming three walls of support.

When Bobby Paul Edwards was sentenced for the crime of forced labor in 2019, Christopher Smith wanted to be heard after years of abuse. Here …

Whaley began reading his statement out loud, describing the endless hours of work without pay, the racial slurs and the beatings.

“I felt like I was in prison. Most of the time I felt unsafe, like Bobby could kill me if he wanted. That would make me stay awake many nights worrying about what he was going to do next. I wanted to get out of that place so bad but couldn't think about how I could without being hurt.”

Yet Edwards no longer controlled his life.

“Today, I feel free, out of the prison Bobby had me in.”

When Whaley finished reading it, the judge asked Chris if he wanted to add anything.

Chris said he forgave Edwards. “That's what the Bible says: Forgive those that do wrong to you. That's what I'm doing. I'm forgiving him for what he done.”

He also wanted Edwards locked up for the maximum sentence.

But the sentencing guidelines, which took into account things like Edwards’ lack of major criminal history, called for nine to 11 years. Harwell came down in the middle at 10.

“Exploiting people like Mr. Smith, who are vulnerable — and doing it for profit — really has no place in any civilized society,” the judge said.

Chris stood, shaken. Ten years seemed so short given all that Edwards had done to him.

•••

The year Edwards pleaded guilty, the National Human Trafficking Hotline identified 156 cases in South Carolina.

Of them, 107 involved sex trafficking. Only 34 involved labor trafficking. Seven involved both.

Nobody thought labor trafficking was rare. But the state task force charged with addressing the problem lacked a way to gather comprehensive data about incidence or to ensure police were trained to recognize it.

The General Assembly had created the task force but not given it any money.

•••

At Edwards' sentencing, the judge also ordered him to pay Chris $272,952.96 in restitution, based on Chris’ typical 104-hour workweek and the federal minimum wage.

That prompted a new whirl of legal action.

Federal prosecutors appealed, arguing the Fair Labor Standards Act entitled Chris to twice that amount.

In April 2021, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.

How much of that money Chris will see is uncertain. If Edwards gets a job after his release, he will be put on a payment plan. But he is unlikely to earn enough to pay Chris the $545,905.92 he owes.

Then, in September 2021, Chris and his attorneys settled the civil case with Edwards’ brother and Half Moon Inc. for $500,000. Of that, about $200,000 will pay Chris’ attorneys for their work.

Chris' money went into a trust and can be used only for his benefit, although he doesn’t have access to it yet. He and his lawyers are still wrapping up legal loose ends.

A month after the settlement, Harwell rejected Edwards’ motion to vacate his sentence.

The final court case was over, seven years almost to the day after Chris was rescued.

Edwards is now federal inmate number 32836-171. He is 57 years old and housed at a medium-security prison in Maryland.

His release date is set for 2026.

Back in Conway, the roof of the restaurant he ran is painted bright blue. A giant "Grand Opening" sign still stretches across the roof. Beneath it, two "FOR SALE" signs hang in the front windows.

Vehicles pass what for decades was J&J Cafeteria. Today, it bears a "Grand Opening" sign and "FOR SALE" signs after another restaurant tried to open in the space. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

•••

Driving toward Myrtle Beach, billboards now urge people to call the human trafficking hotline for help and to report tips.

In Conway, police officers have gone through a block of online training in human trafficking offered by the state’s criminal justice academy. Most have also completed other training, the city’s spokeswoman said.

But much work remains.

At the Statehouse, key agencies are pleading for help combating the problem.

SLED is asking for two more human trafficking investigators. It now has two and a supervisor handling a huge uptick in cases due to better training and networking with local police. In 2021, the unit opened 34 human trafficking cases. Over just the first six weeks of 2022, they already have opened that many cases: 34.

Meanwhile, the attorney general’s budget requests a new data specialist to gauge the problem’s scope and track who has received professional training.

“It’s a real crisis,” said Kathryn Moorehead, director of the South Carolina Human Trafficking Task Force. “The system is just getting swamped with these cases.”

Her group is pressing for any state funding at all.

With it, Moorehead would focus on ensuring consistent training for those who work the frontlines of police and human services. She also would open more emergency shelters and long-term residential programs for victims, given the state has very few.

Because Caines opened her home to him, Chris did not need an emergency bed. That was fortunate, given the state has none for labor trafficking victims.

•••

Today, Chris is 43 and lives with his mother and his sister, plus her two children and her 60-year-old father, who has advanced cancer.

Chris sleeps on a dark gray couch facing the kitchen.

Barr, his sister, would like to find a bigger place where Chris would have his own bedroom. But she works as an in-home caregiver. Chris works at a country fish market. Money is tight.

Barr takes care of Chris, although she doesn’t like to call it that. More like steering, she says, things like getting him to appointments and making sure he heads out the door to his job. He works four days a week now, not seven.

Chris Smith (left) cracks jokes with his friend Malcolm Rick Sheppard while riding the Coast RTA bus to work. Chris mentions a police investigation at an abandoned house he saw before they start chatting about movies to watch. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

He leaves home just before lunchtime and walks about a mile to a bus station, crossing busy roads, cutting through a church parking lot, yucking it up with friends he runs into along the way. He plods silently past the Dollar General where the waitresses bought bandages to treat the burn on his neck that day years ago.

Silver streaks his beard, and he trods with a limp. But his shoulders have filled in. His cheeks are plump.

Sometimes he still wonders about all the people who heard him screaming. Why didn’t they help him?

But most days he smiles. He is free.

At the station, he hops aboard a public bus and rides to Freshwater Fish Co., a cozy family-owned market and restaurant surrounded by towering pines. On days Chris arrives early, he hangs out with Linda Brown, whose son owns the fish market. She works there, too, and lives next door.

While greeting customers at the Freshwater Fish Co. in Conway, Chris Smith jokes around while gathering takeout orders. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

Soon he is cleaning fish, then mopping up a water spill. He wears jeans that look new, a white T-shirt and a bright blue apron. It ties around his neck, covering most of the burn scar.

The fish market’s inside dining is closed due to COVID, so when a customer arrives, Chris hurries away to bag up the man’s order.

Brown watches him go with a mother’s smile.

“We love Chris,” she says.

He disappears into the kitchen where he jokes with the cook, his giggle bubbling out and spilling across the dining room.

This telling of Christopher Smith's story relies on court records and investigative documents from various state and federal agencies involved…