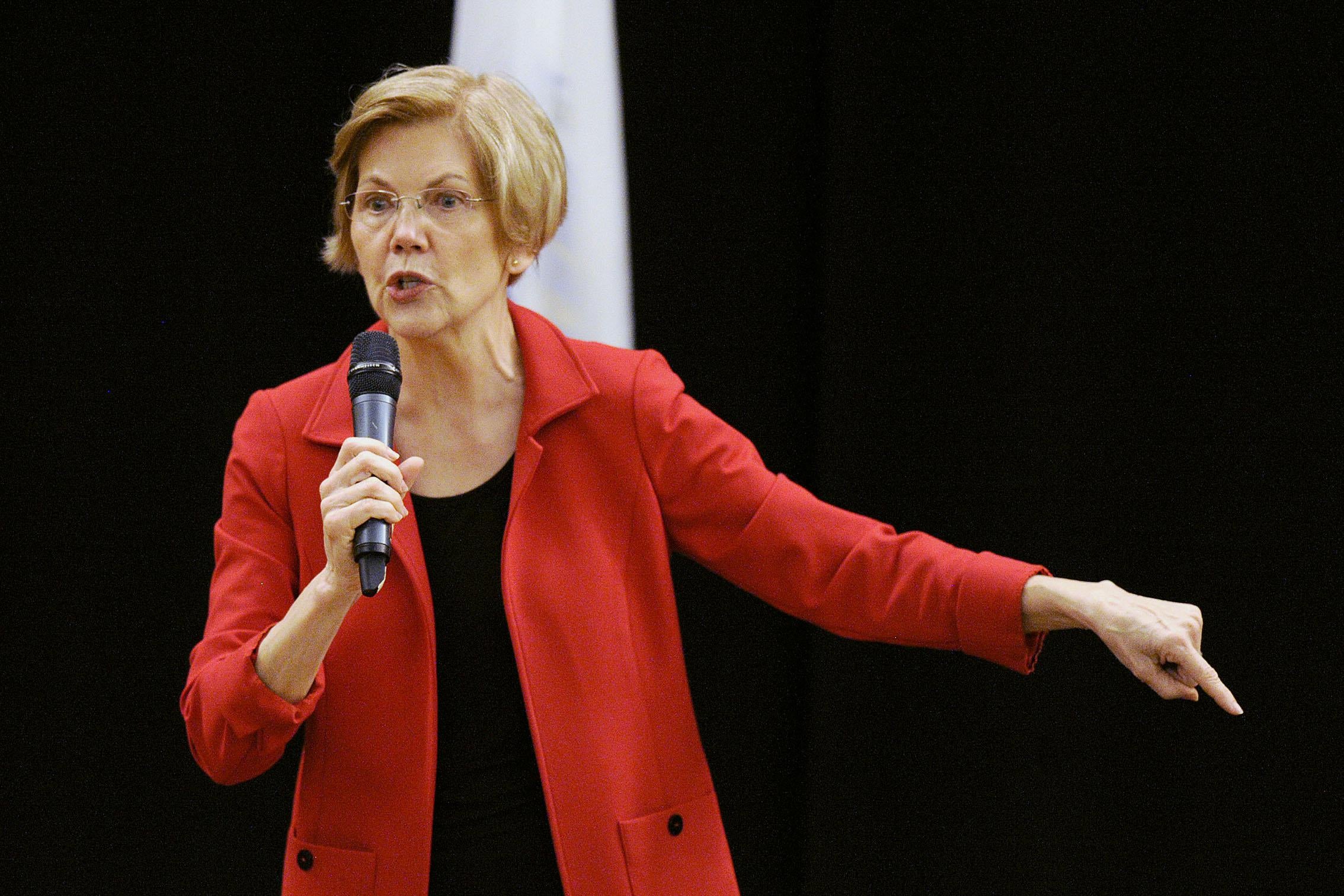

On Monday afternoon, after a half day of debate over Elizabeth Warren’s announcement (with a campaign-style video) that she had taken a DNA test and found evidence supporting her claim of having a Native American ancestor, the Cherokee Nation—of which Warren had primarily claimed an ancestral affiliation—released a scathing statement condemning the whole affair:

Using a DNA test to lay claim to any connection to the Cherokee Nation or any tribal nation, even vaguely, is inappropriate and wrong. It makes a mockery out of DNA tests and its legitimate uses while also dishonoring legitimate tribal governments and their citizens, whose ancestors are well documented and whose heritage is proven. Senator Warren is undermining tribal interests with her continued claims of tribal heritage.

In the statement, Cherokee Nation Secretary of State Chuck Hoskin Jr. emphasized a point that Native American activists have been making all day: A DNA test is irrelevant—and can even be harmful—when it comes to determining tribal citizenship and heritage.

While many of President Trump’s critics have pointed out that the president has repeatedly used a slur, Pocahontas, to mock Warren’s claim to Native American ancestry, some Native Americans have said that both Trump’s overt racism and Warren’s claims to an indigenous identity should be criticized as harming the national understanding of indigenous identity and rights.

The primary complaint about Warren’s place in this affair has to do with her use of a DNA test to seek out evidence of a tribal ancestor. According to several activists and experts whom Slate spoke to Monday, the use of a genetics test—setting aside the unreliability of those tests—indicated that Warren was buying into and promoting the notion that it is blood that determines who is and is not American Indian.

“There’s this really critical distinction between DNA and ancestry on one hand and identity and belonging on the other,” said Deborah Bolnick, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Connecticut. “These are things based on social connections. Especially in the context of tribal nations—these are sovereign nations with political and legal contexts to them. It’s not genetically determined.”*

Bolnick said she understood Warren’s desire to respond to Trump’s attacks, but she thought Warren’s search for genetic proof to back up her claims was misguided. “I do have concerns that I don’t think we should be looking to genetics to adjudicate these debates,” she said. “It’s suggesting that science, that genetic technologies have answers to questions about identity and belonging.”

Krystal Tsosie, an indigenous geneticist-ethicist at Vanderbilt, said that on a practical level, tribal enrollment matters when it comes to arrangements with the United States government about the tribes’ rights and resources established in treaties. “Access to water, air quality, health care is tied with an individual’s ability to establish ascendancy to an individual Nation,” she said. “External factors that question biologically how we as indigenous individuals call ourselves would be dangerous.”

Rebecca Nagle, a writer and citizen of the Cherokee Nation, said that Warren’s decision to publicly tout a DNA test as evidence of Cherokee heritage had her “terrified” about the ways it could affect the public’s understanding of tribal sovereignty.

Nagle said she was concerned that if the public came to define native citizenship as one of blood and race, Americans with no legitimate link to a tribe could use the unreliable results of a DNA test to claim benefits and rights that tribes earned after being pushed from their lands. To support her argument, she cited the story of a man in Washington who heard family lore of having Native American ancestry, took a DNA test, found he was 6 percent indigenous (and also 4 percent black), applied for the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program on the basis of the test results, and sued the federal government. This kind of behavior, based on DNA, puts programs and rights for indigenous people at risk, she argued.

The Cherokee Nation just this week had decided to challenge a recent decision by a federal judge in Texas who declared a law called the Indian Child Welfare Act unconstitutional. The law, which was passed in the 1970s to prevent the forced removal of Native American children from their tribes, gives tribes the right to intervene in adoptions in which non-native parents adopt native children. The federal judge decided earlier in the month that the law was unconstitutional, based on the Fifth Amendment’s equal protection clause—in essence, arguing that Native American families were being given preferential treatment based on race.

This decision hinges on the notion of native identity as racial, Nagle argued, and if upheld, it could set the precedent for other sovereign rights to be stripped. That conceptualization of identity is wrong, she said, because to be a member of a sovereign nation is a cultural and political matter. After all, Nagle notes, DNA tests could never tell anyone which particular tribe their ancestor belonged to, so someone claiming native identity from a test wouldn’t know which tribe to register with.

Instead of looking to genetics, tribal genealogists can look at the extensive records the tribes have kept of their members to check if someone claiming native ancestry does indeed have legitimacy. Warren participated in the extremely common tradition among Americans of claiming a Cherokee ancestor. While many Native Americans believe the vast majority of those claims are false, if her ancestor had appeared on their records, she would have been accepted into the tribe, Nagle said.

In the video announcing the test results, Warren did clarify that she was talking only about family history and not claiming any sort of right to affiliation. “I’m not enrolled in a tribe,” she says in the video. “Only tribes determine tribal citizenship. I understand and respect that distinction.” Later Monday, she reinforced the message with a tweet: “DNA & family history has nothing to do with tribal affiliation or citizenship, which is determined only—only—by Tribal Nations.”

But some considered the statement far too late—she had, after all, claimed Native American identity at Harvard Law School in the 1980s, and she listed herself as Cherokee in a local Oklahoma cookbook titled Pow Wow Chow.

Some have said that Warren crossed a line, after years of holding on to her claim of Native ancestry, but others have said there is still room for her to make amends with the Cherokee people.

Joshua Thompson, an accountant and member of the Cherokee Nation, said that he wants an apology from Warren. What Warren was doing was unequivocally racist, he said—just as Trump’s use of slurs is. “I would prevail upon her good senses,” he said. “She’s a rational, thoughtful, good human being who is doing something that’s bad right now. Be better.”

Update, Oct. 16, 2018: A quote from Deborah Bolnick was updated.