How the Politics of Race Played Out During the 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic

Free blacks cared for the sick even as their lives were imperiled

:focal(396x205:397x206)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/64/7f647e5d-d45d-4930-a975-cd845400148f/untitled-1.jpg)

It was 1793, and yellow fever was running rampant through Philadelphia. The city was the nation’s biggest at the time, the seat of the federal government and home to the largest population of free blacks in America.

Foreigners were to blame, said one political faction, charging that immigrants were bringing the contagion into the country and spreading it from person to person. Another political group argued that it arose locally and was not contagious. A fiercely divided medical community took opposing sides in the argument over where the contagion came from and disagreed on how best to treat the disease. Federal, state and local officials and those with resources fled the city, while a huge number of people of color—falsely believed to be immune—stepped up to care for the sick and to transport the dead, even as their own communities were disproportionately hit by the disease.

Scholars at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History recently revisited that 1793 outbreak in the online seminar, “Race and Place: Yellow Fever and the Free African Society in Philadelphia,” as part of the museum’s ongoing Pandemic Perspectives. The virtual seminars aim to put today’s Covid-19 global pandemic into context and to give participants a deeper dive and analysis of the museum’s collections.

Curator Alexandra Lord, who moderated a panel of medical professionals and historians, says that socioeconomic and racial disparities were on full display in 1793 as they are during the current pandemic. “Those who could flee tended to escape the disease,” she says. The political and financial elite picked up and left the city. An estimated 10,000 to 20,000 of Philadelphia’s 50,000 residents fled.

But two free black men, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, were relentless in their drive to bring humanity to those who had found their way to Philadelphia. Allen was born enslaved in the city in 1760 and later purchased his freedom. Jones also had been born into slavery in Delaware had obtained his freedom through manumission in 1784. The two joined forces in 1787 to form the Free African Society, a social welfare organization that provided financial support, sick relief and burial aid.

The Society also created The African Church, which later split, with Allen—who established the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church at Mother Bethel AME—and Jones establishing the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas.

Yellow fever was not entirely unknown at the time. It originated in Africa with colonizers and slave ships bringing it to the Americas in the 1600s. Most got the disease and survived. But a small percentage succumbed to its toxic form, which caused high fever and jaundice—a yellowing of the skin and eyes—hence its name. Other symptoms included dark urine, vomiting and sometimes bleeding from the mouth, nose, eyes or stomach. Half of those who developed this form died within a week to 10 days. Yellow fever arrived in the U.S. from the West Indies. In the 1890s Army doctor Walter Reed confirmed a Cuban physician’s hypothesis that mosquitos spread the disease. It wasn’t until the 1930s that the virus that caused the illness was discovered.

Before the epidemic had run its course in December 1793—mosquitos did not survive the cold—the Irish-born economist Mathew Carey, who had stayed in the city to help, decided to publish his observations in a pamphlet, A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia.

Carey described in vivid detail how the epidemic came to Philadelphia, the symptoms and treatments, how the citizenry fled, and how those who stayed coped—some by constantly chewing garlic or carrying it on their person, smoking cigars (even small children were given cigars), and incessantly “purifying, scouring, and whitewashing their rooms.” People avoided barbers and hair dressers, they deserted their churches, and they closed libraries and coffee houses.

“Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod,” wrote Carey. “The old custom of shaking hands, fell into such general disuse, that many shrunk back with affright at even the offer of the hand.”

“In 1793, there were two leading schools of thought within the medical community about yellow fever,” says David Barnes, a University of Pennsylvania medical historian, who participated in the seminar. Many American doctors—most of whom were centered in Philadelphia—believed it was imported from the West Indies and that it was contagious, spreading from person to person. Others believed it was not contagious and not imported, but that it originated in the city in accumulations of filth, says Barnes. The faction who believed in contagion advocated cold baths and quinine—proven against malaria—and imbibing alcohol, as it was believed to fortify the body.

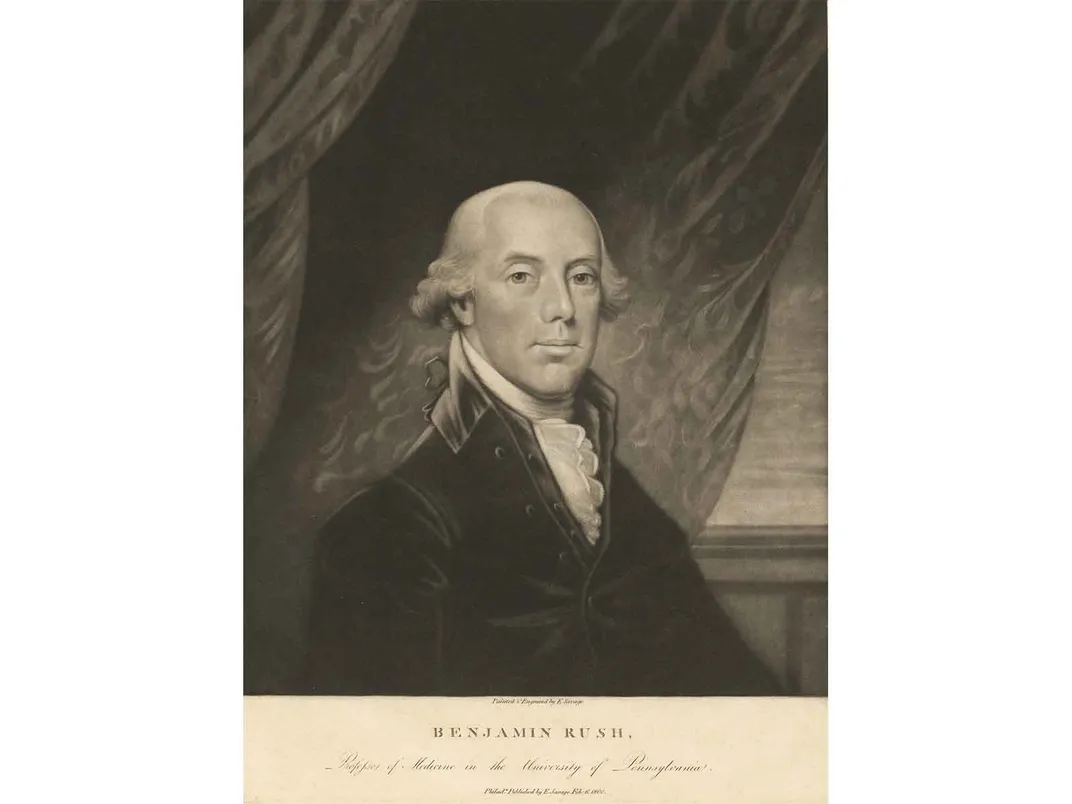

Philadelphia’s leading physician, Benjamin Rush, was a non-contagion believer. He thought the 1793 outbreak “originated in a shipment of raw coffee beans that had been left to rot on the wharf near Arch Street,” and that it was the stench, or “miasma” that caused the illness, so he advocated for cleaning up the city instead of closing the port, as the contagion believers desired, says Barnes.

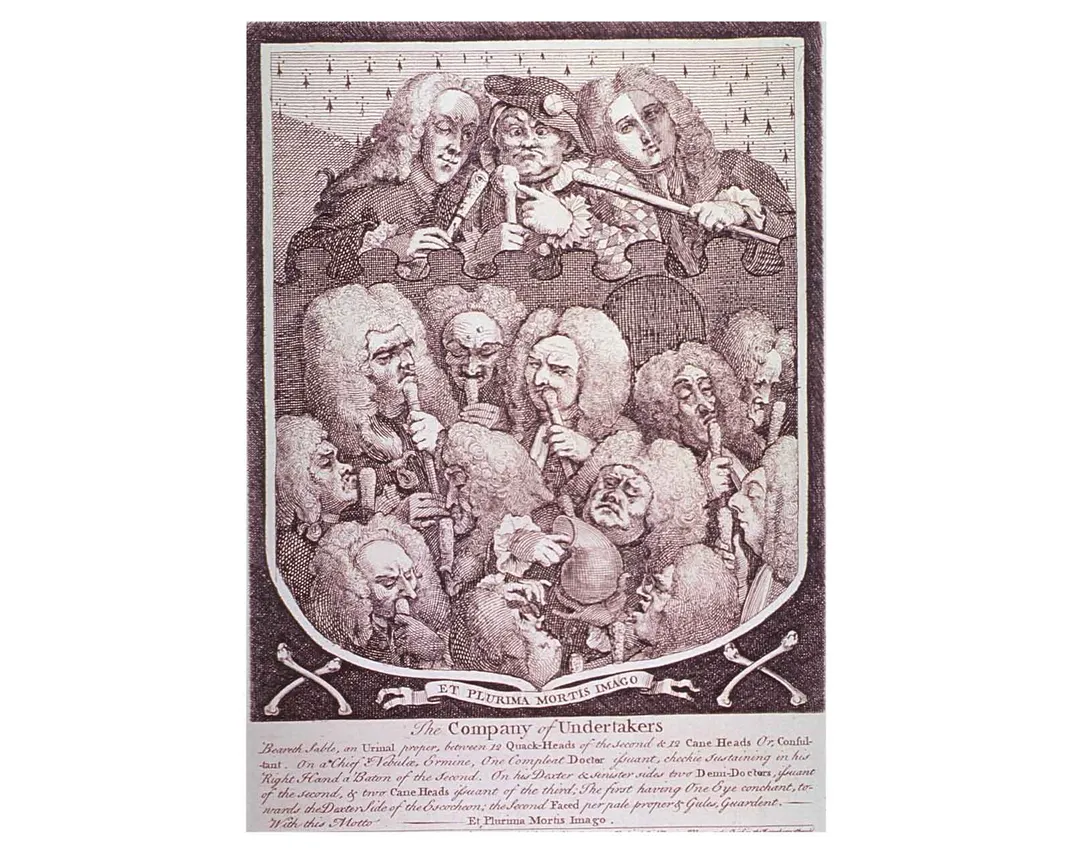

Physicians in the late 18th century weren’t anything like today’s medical professionals. There were no true medical schools and doctors were “often the subject of suspicion and even hostility,” says Simon Finger, a medical historian with The College of New Jersey.

Many of their cures did not work and they were seen as unethical—charging fees that were regarded as extortion—and their practice of digging up bodies in cemeteries for dissection and study didn’t lend them much credibility, either, says Finger, who participated in the talk.

To counteract the negative image and to advance knowledge, Rush and colleagues joined together in 1787 to form the College of Physicians in Philadelphia. “What’s happening in 1793 is a really delicate moment in which physicians are working really hard to establish the respectability of their profession at a time when the public is skeptical of them,” says Finger.

Rush aggressively treated yellow fever by opening veins with lancets and letting the patient bleed out a pint or more, and by purges, which caused copious diarrhea, says Barnes. The measures were aimed at bringing fever down and depleting the “excesses” that Rush believed accumulated from the disease.

He was rarely questioned, says Lord. But Rush’s training of volunteers from the Free African Society in how to administer his purported treatment went a step too far. It fractured the College of Physicians. Rush ended up starting a rival academy of medicine, Finger says. It “was controversial at the time, having Africans do blood-letting,” adds Vanessa Northington Gamble, an American studies scholar and medical historian at George Washington University and also a panelist.

Free blacks played a crucial role in the epidemic. Thousands of formerly enslaved people had come to Philadelphia to exercise their newfound freedom. Gamble estimates that in 1790, some 2,100 free black people made their home in the city, while an additional 400 were enslaved. One of the most prominent slaveholders was President George Washington—even though Pennsylvania had essentially outlawed slavery in 1780.

As yellow fever began ravaging Philadelphia, people were dying by the dozens daily. With much of the city’s officials and the wealthy fleeing the contagion, “there were not enough people willing to tend to the sick or bury the dead,” says Barnes.

Rush put out a call for help from Allen and Jones and their Free African Society, in part because he and others believed Africans were immune to yellow fever, says Gamble. This theory was integral to a broader view of black bodies that was used to support slavery—that they were less susceptible to certain illnesses.

The Free African Society was established to help blacks, not whites. And yet Allen and Jones answered Rush’s plea. “They wanted blacks to take care of their white brethren so they’d be seen as human beings,” says Gamble.

It turned out to be a deadly duty. Statistics from the time are not reliable, but it is estimated that as many as 5,000 died including 200 to 400 black Philadelphians, during the six-month epidemic. Allen got the disease himself, but survived.

In his pamphlet, Carey had damning words for George Washington and other officials, but heaped praise on the handful of white citizens—merchants, clergy and physicians who did not flee and often died even as they attempted to meet the needs of the poor. He observed that the poor were disproportionately sickened and more likely to die, but that newly-settled French citizens had somehow been spared.

Despite the Free African Society’s many volunteer efforts, Carey devotes just one paragraph to the black population, repeating the claim they were immune to yellow fever, with a caveat. “They did not escape the disorder; however, there were scarcely any of them seized at first, and the number that were finally affected, was not great,” he writes. While black Philadelphians eagerly volunteered for nursing, as the white population cowered, Carey claimed that black nurses took advantage of whites with exorbitant fees. “Some of them were even detected in plundering the houses of the sick,” he reported. Still, not all were bad, Carey acquiesced. Services provided by Allen, Jones, he wrote, and “others of their colour, have been very great, and demand public gratitude.”

But Allen and Jones were infuriated by Carey’s inaccurate reporting. In 1794, they responded with their own pamphlet, A narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a refutation of some censures, thrown upon them in some late publications. They wrote that they “worked at the peril of our lives,” says Gamble. “These are African Americans in the 18th century who stood up to someone maligning their community,” she says.

Nor did they forget the attack.

“The next time there was a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, black people stayed home and took care of each other, and not the white community,” says Gamble.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)