In 1970, as the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrim landing approached, Frank James, a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), was invited by Gov. Frank Sargent to write and give a speech at the ceremony.

But when James shared his speech with state officials, he was told it was too aggressive and extreme. They asked him to read a statement written by a public relations professional.

James refused.

In his speech, James compared the white culture and the Native culture, how one conquered and pillaged and the other was enslaved or forced to assimilate. One thought it must control life and profit off it, and the other believed life was to be enjoyed because nature decreed it. One was portrayed as organized and disciplined, and the other as savage and uncivilized.

“We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end,” James wrote, “that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.”

The censorship angered local Native people and helped spark the creation in 1970 of the National Day of Mourning — a gathering held every Thanksgiving on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth to honor indigenous ancestors and the struggles that Native people face today.

“That just further fueled the fire that after all these years, you’re still trying to filter what we say,” David Weeden, historic preservation officer for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, said of James being censored. “You’re still trying to paint the actual history and tell a version of history, of what happened, reluctant to acknowledge the fact that Native Americans are still not being treated equally or justly or not have a fair shake.”

Even before James, who died in 2001 at the age of 77, was censored, Weeden's father, Everett "Tall Oak" Weeden, had watched Native people demanding civil rights and recognition in other parts of the country in the late 1960s.

Indigenous civil rights organizations demanded recognition and raised awareness about the injustices taking place in several places around the country in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In November 1969, "Indians of All Tribes" occupied Alcatraz Island off San Francisco for 19 months.

In 1970, demands that Mount Rushmore be returned to the Sioux led to a group of Native American activists climbing the mountain and occupying it for months.

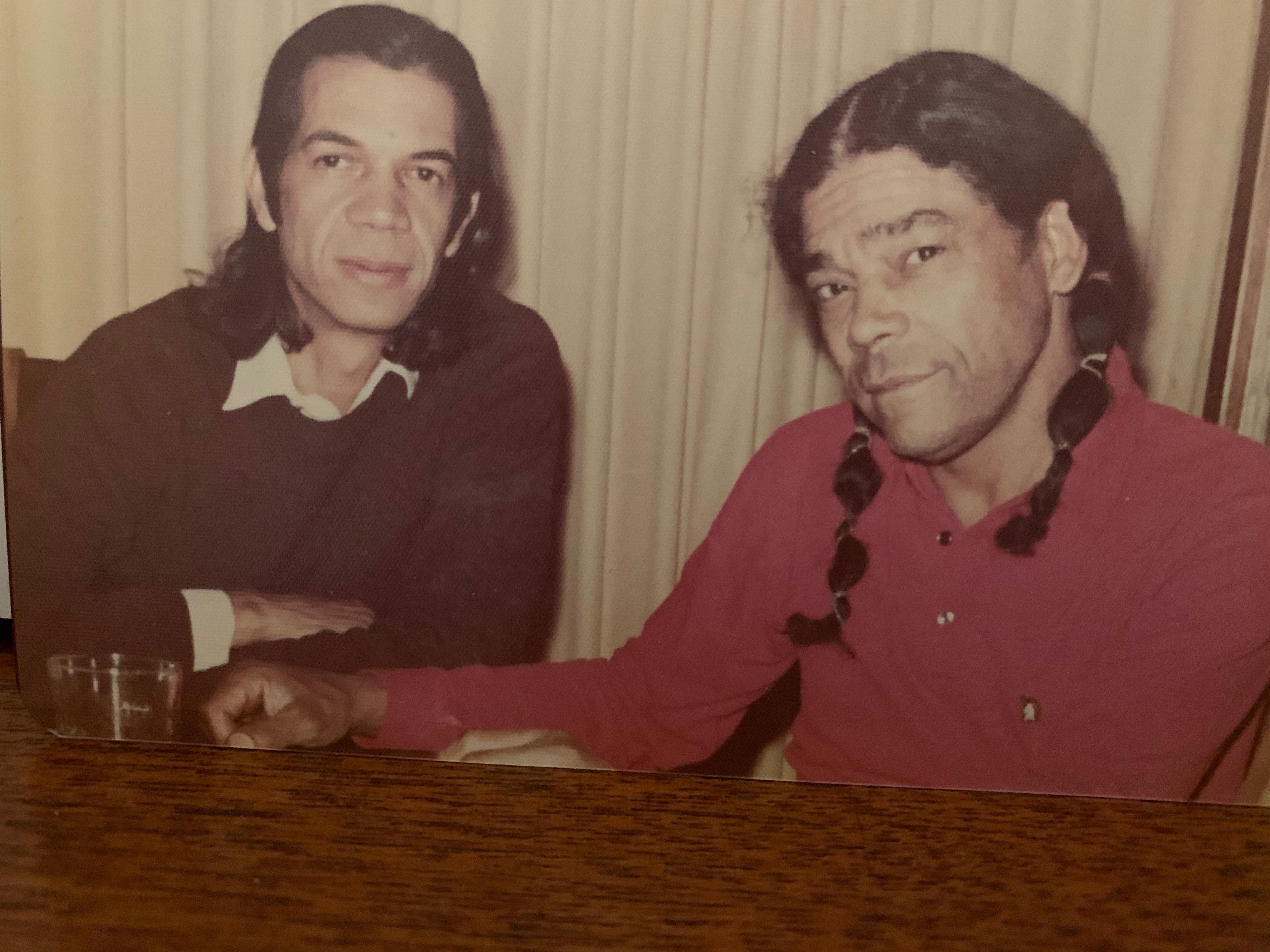

With this as the backdrop, around the same time James was censored, Tall Oak, a descendant of the Mashantucket Pequot and the Wampanoag, traveled to Connecticut for a gathering of Native Americans. While there he approached his friend James Fraser, who is Cherokee and Edisto, to discuss what happened to James.

As they sat in Tall Oak’s blue Volkswagen Beetle, they brainstormed ways to put a national spotlight on the eastern tribes and the injustices they faced.

Tall Oak, now 84, and Fraser, now 91, sought out four other Native Americans to help with the planning, and together they organized the first Day of National Mourning.

James, who taught music at Nauset Regional High School; Gary Parker; Shirley Mills; and Rayleen Bey gathered with Fraser and Tall Oak multiple times to plan.

The six originally planned their gathering for Jamestown, Virginia, but later decided to hold it in Plymouth, where the Mayflower landed and a statue of Ousamequin, also known as Massasoit, which means "Great Sachem," stands looking over Plymouth Harbor.

The group organized speakers and developed a list of issues to discuss. They also spread the word across the country and arranged lodging for people who planned to attend the event.

Their biggest objective was to make sure the event was peaceful, Fraser said. No threatening or fighting words would be spoken.

“It was the intent of the initial six of us that our observance on Thanksgiving would be a solemn occasion to bring attention to the eastern Native people that are still here,” said Fraser, who lives in Lexington.

Part of their mission was to enhance relationships between Native and non-Native people on Cape Cod, Fraser said. The event would have no ethnocentrism, no discussion of one culture being better than another. It would teach acceptance and cultural appreciation, he said.

The first National Day of Mourning was held on Thanksgiving 1970. Almost 500 Native Americans from across the country gathered at the statue of Massasoit. James gave a keynote speech, which was more tempered than the original speech he had prepared to give at the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing, Fraser said. They wanted a peaceful event that would inspire a connection between Natives and non-Natives.

“It was thought that all hell was going to break loose at the first National Day of Mourning,” Fraser said. “There were undercover police officers. And there were cameras going, capturing pictures of those who had gathered.”

Fraser remembers walking around the parking lot and seeing license plates from Arizona, New Mexico, Virginia and North Carolina. He walked around while people were eating and did a head count, and stopped at 477 people.

“It turned out to be a very lovely day,” he said.

The National Day of Mourning is still held every year in Plymouth on Cole’s Hill. On Thursday, people will gather for the 50th year and march through the historic district of Plymouth.

Fraser said he and Tall Oak, who lives in Charlestown, Rhode Island, no longer attend the yearly event. But Fraser helped with an exhibit that the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., is planning for the National Day of Mourning, although COVID-19 delayed the preparation, Fraser said. A movie is also in the works.

David Weeden remembers going to the National Day of Mourning as a child.

“It was all Natives in the early period and there was a lot of solidarity,” he said. “It felt good to be there.”

In the early days the event would focus specifically on injustices Native Americans in the New England region faced, he said, but it now involves a wide range of issues, such as the environment and climate change.

Those issues that Native Americans first discussed 50 years ago at the statue of Massasoit are the same ones tribes are fighting for today. They fight for their aboriginal rights, the ability to hunt and fish, and to keep their sovereignty, Weeden said.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, for example, continues to fight to keep its land in trust and the reservation it established after officially receiving federal recognition in 2007, he said.

The discomfort that non-Natives felt from James' speech in the '70s carries on today. Weeden said when Native Americans start talking about issues that are relevant to them today, the more privileged members of society get uncomfortable, wanting them to tone down their feelings.

“Acknowledging that wrongs have been done is the first part of healing,” Weeden said, “and until wrongs are acknowledged and responsibilities have been taken for those wrongs and injustices, you’re just perpetuating what’s already been done.”

Despite this, one of the original goals of the National Day of Mourning was to find a connection and peace between Natives and non-Natives.

James’ original speech also ended on a hopeful, uplifting message.

“What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work toward a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth and brotherhood prevail.”

Contact Jessica Hill at jhill@capecodonline.com. Follow her on Twitter: @jess_hillyeah.