In near darkness, a local rapper stands on a Nashville stage. Backlit, he cuts an imposing figure, broad-shouldered and burly.

The lights come up to reveal a robe-clad chorus and a black-clad band behind Antioch native Jason “Jelly Roll” DeFord, his face tattoos and mullet-hawk hairdo looking more Rock Block than Music Row — his leather jacket and flashy jewelry looking more Hickory Hollow than Green Hills. The seriousness of the mise-en-scène is undercut by the ear-to-ear smile across Jelly Roll’s face.

Tonight are the 2023 CMA Awards at Bridgestone Arena, and DeFord is nominated for five awards: Music Video, Male Vocalist, Musical Event, Single and — in a delightfully ironic turn for a guy who has been grinding for more than two decades — New Artist of the Year. His circuitous route from the shores of Percy Priest Lake to country music’s biggest stage was long and hard, stacked with tragedy and challenges, prison stints, addiction and death. The fact that DeFord is alive at 38 goes against the odds, and the fact that he’s standing onstage, arm in arm with Wynonna Judd, singing his hit “Need a Favor” seems nothing short of miraculous.

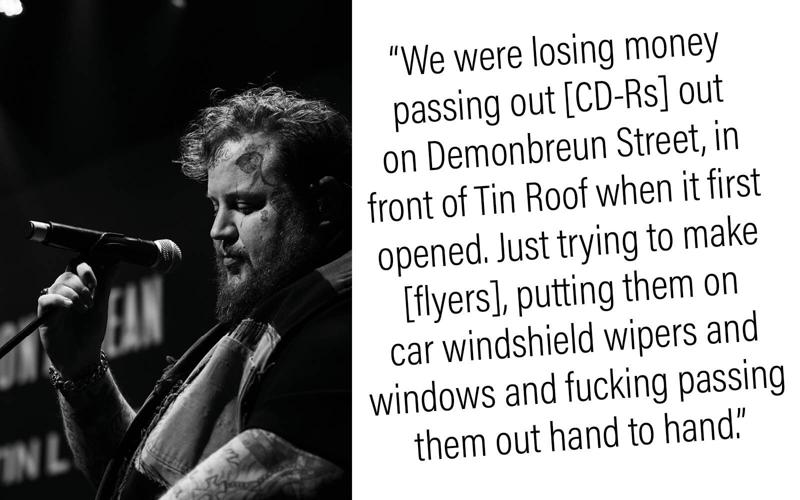

“[It’s the] same approach that I’ve had from being a 15-year-old kid passing out fucking mixtapes in Antioch High School to right now, same approach,” DeFord tells the Scene by phone from the road. He’s on his way to show 50 of 55 on the Backroad Baptism Tour, a tour that has seen him sell out amphitheaters and arenas across the country. “Dealing with people the same way. Creating relationships, loving all people, fucking just being who I am all the time.”

DeFord’s Nashville roots are as deep as his success is unlikely. The first decade of his career was spent deep in the Tennessee hip-hop underground, during an era when the Nashville industry was dismissive if not openly hostile to hip-hop, homegrown or not. The outside world was not much more receptive to the idea of rap from the country music capital of the world. He was making stark, dark, confrontational Southern hip-hop while critics — this one included — were enamored with shutter shades and Daft Punk samples.

This decade of DeFord’s creative life was bookended by periods of incarceration — at age 16 for aggravated robbery and again at 23 for selling drugs — that only added to the challenge. Any gains made in street cred were diminished by the state-mandated restrictions on travel and economic access, two essential things for launching a long-shot career in music. But DeFord was still out there hustling, grinding — if you participated in Nashville nightlife at any point during the Aughts, he likely put a flyer in your hand.

“The wildest place I’m at in my life, Sean, is that I am making — I don’t even know how to talk about it — weird amounts of money to do something I’d do for free,” says DeFord. “We were losing money passing out [CD-Rs] out on Demonbreun Street, in front of Tin Roof when it first opened. Just trying to make [flyers], putting them on car windshield wipers and windows and fucking passing them out hand to hand.

“You were trying to get 50 people to come see you at the Kung Fu Coffee House — aka The Muse, which is now a fucking paint store and a Domino’s.”

The pride you hear in his voice when talking about performing at off-the-beaten-path venues like the now-shuttered Playing Field in Antioch or the long-running Rivergate saloon Silverado’s — “we played all those Tennessee clubs” — belies that fact that one year ago he sold out Bridgestone Arena, the same venue that hosted last week’s CMA Awards. Part of the reason this year’s Whitsitt Chapel — Jelly Roll’s latest, and his first foray into country music — is so successful as a work of art is because the songs and the album exist within these places, out of the way and off the radar.

The real Whitsitt Chapel is out by Percy Priest, off Bell Road, about as far from the downtown centers of fashion and power as you can get while still in Davidson County. The same can be said of the album’s spiritual center. “Need a Favor,” the January 2023 single that hit No. 1 on the Billboard Country Airplay and Hot Rock & Alternative Songs charts, is a stadium-sized sing-along of gutter bravado and desperation, wavering faith and existential examination. It’s also a testament from a dude that done fucked up.

“Behind Bars,” a country-rap collaboration with Brantley Gilbert and DeFord’s longtime creative foil Struggle Jennings, feels like the last day of probation, a gallows-humor offering at once worried and relieved. And “Save Me,” which features fellow breakout star Lainey Wilson, is the kind of tear-in-my-beer belter that made this city great; it’s an anthem for anyone who has ever closed out a small-town karaoke night while trying not to cry. Throughout Whitsitt, country, rock and hip-hop moments break bread with classic revival inspirations and contemporary praise-and-worship underpinnings. It all feels more real, more connected to a place and time and people than the “Saturday nights dancing in headlights” stories we typically hear on country radio.

Genre is more about the industry’s need to organize product than a reflection of actual listeners’ actual listening, so Whitsitt Chapel popped off like buckshot, scattering songs all over the Billboard charts. Songs from the album ended up on the Hot 100, Hot Alternative and Hot Country charts, along with the aforementioned history-making twofer — “Need a Favor” landing in the top spot on both the Country Airplay and Hot Rock & Alternative charts. And just days before this story went to press, DeFord was nominated for a pair of Grammys — one for Best New Artist, and another for Best Country Duo/Group Performance for his collaboration with Wilson. Not bad for a dude who sold his homemade rap CDs outside the Percy Priest Mapco.

“If they would’ve had a ‘Least Likely to Succeed’ in Cameron Middle School, I probably would’ve made it, you know what I’m saying?” says DeFord. “I’m having the time of my fucking life out here. I’m having a ball. It’s true. It’s a real thing. I think that God blessed me, because if God would’ve gave me this success and this platform 10 years ago, I’d have died of a drug overdose.”

“You want to be a good songwriter, you start getting good around song 600, 700,” DeFord tells the Scene. “Same thing with shows, man. You don’t really understand how to work a crowd or what is and isn’t corny until you’re 500 in.”

A little more than a decade ago, DeFord was undergoing a rapid creative transformation. Shortly after leaving the prison system for the second time, armed with a GED and a sense of urgency, he signed with Hypnotize Minds, the legendary Memphis label founded by DJ Paul and Juicy J. He released Year Round with Bluff City rapper Lil Wyte and BPZ. It was the first of three albums with Lil Wyte. There were also collaborations with fellow local rapper Haystak, and then, of course, there was The Big Sal Story. That was the project where we really started to see glimpses of the enormodome-ready Jelly Roll we know today.

“The fact is that as I got older, I fell in love with the guitar, and I fell in love with the piano, and I fell in love with producing records,” DeFord explains. “I fell in love with the music side of things.”

The 2017 album Addiction Kills was the one that pointed toward DeFord’s future, a complicated take on a phenomenon that devastates country and city alike. DeFord dove deep into our city’s top export, country music, for four Willie & Waylon volumes with fellow product of the Tennessee corrections system Struggle Jennings. After making still more solo albums, a decade out of lockup he’d established a sustainable career as an independent musician, built from internet savvy and boots on the ground.

And then “Save Me” happened. First released in June 2020, it’s a sparse and distraught song about struggling with addiction, grief and loss, and its rawness embodies the zeitgeist-defining desperation we were all feeling that summer. Something about the line, “All of this drinking and smoking is hopeless,” connected with an America that had been stuck at home, drinking and smoking for months. A live-performance video of “Save Me” shot at Sound Emporium Studios on Belmont Boulevard went on to generate 199 million views on YouTube and set the stage for a new decade of creative and commercial success.

“When I was in my jail sentence at CCA, I was in a program called Jericho by the Men of Valor,” says DeFord. “It’s a Christian faith-based program [that was] on Harding Place at the time, and I’ll never forget, there was a conflict in the dorm one day, and the head guy whose name was Kirk Campbell, walked in and he said, ‘Look y’all, I want to be clear about this. If I put 60 of the biggest pastors in America in this room and they slept together, ate together and lived together the way y’all do, there would be a fight. For sure.’ And when he said that, that was such a real thing. He’s like, that’s just the nature of being in a submarine together.”

DeFord takes serious pride in steering his huge ship. The Backroad Baptism Tour had a small army of 68 people traipsing with him across the country, and he brags about bringing a registered nurse on tour and keeping his crew and artists healthy on the road. He’s an artist who did everything himself for so long that being a good boss and crewmate is important, and he wants to make sure everyone — from the audience to venue staff — is having a good time. He is both Phil Margera and Bam Margera rolled into one, at once the wild child and the exasperated dad.

“Dude, we’re 11 weeks into a five-show-a-week tour, and everybody’s still very harmonious,” DeFord says. “And if you’ve ever been a part of a tour like this, there’s normally a fistfight that’s happened in the parking lot by now.”

“I come from a culture where they used to use the term, ‘There’s no big I’s and no little you’s.’ I don’t know if you’ve ever heard that term. But it’s ‘no big me, small you’ thing. I feel like everybody should be treated the same way on a tour, and that’s important. It keeps the morale up. “

Fast-forward to the first Monday in November, and DeFord is firing on all cylinders. He’s at Bridgestone, this time rehearsing for the CMAs, where he’ll be in the opening and closing numbers. He’s nominated for five awards — second only to his “Save Me” remix partner Lainey Wilson, who’s up for nine. The Scene has managed to score 15 minutes of junket time from a major television network’s promotional apparatus, and you can almost hear the quizzical looks from his handlers as we deep-dive into the history of Smyrna and La Vergne youth sports.

“I did that toy drive at the Antioch [Walmart] location, four minutes from the La Vergne [city limits], and I was talking to the store manager,” says DeFord. “I said, ‘You want to know how old I am?’ He said, ‘How old?’ I said, ‘I remember when this was a slab of dirt.’”

DeFord has been home from tour for a couple weeks, but he’s been busy launching the ambitiously named “Biggest Toy Drive in Nashville History.” He’s playing pop-up shows in Walmart, where his admission is a toy donation, cramming in a mini tour for charity before he heads out to the East Coast to headline iHeartMedia holiday shows. DeFord, who throws money at good causes like rock stars of yore threw televisions from hotel rooms, is a frequent visitor to juvenile offender programs and does a lot of prison outreach. He even paid to send a high school softball team to a tournament just because he saw them selling pizzas to raise money for airfare.

“I just think I’m so blessed I should be a blessing,” says DeFord. “I came from charity. I’ve been in the car that went to the food bank at the local church. … I’ve been indigent. I’ve been on the free lunch program. I’ve been into these things. I’ve been in jail. I’ve had to have a public defender. I couldn’t afford a lawyer. You get in these situations in life.”

“My first Christmas home in 2009 when I got released from jail … I had a newborn daughter, a little bit over a year old, almost 2, and I couldn’t afford any Christmas presents,” he says. “I was living in a halfway house, and mentors donated gifts to that halfway house for our children. So I remember taking a car full of stuff that I didn’t buy for my daughter to drop off at her house with my name on it.”

DeFord is passionate about doing good things with the “weird” money that has stacked up since “Save Me” launched him into the stratosphere, and you can almost hear his Music Row, media-trained politeness strained to capacity when he talks about celebrities who do the bare minimum for charity. (“Quit being a cheap fuck. You’re a millionaire. Write a check.”) He talks about helping at-risk kids and what we as a music community can do to help (“We’re going to live to see that generation be our mayor — we need to start investing now”) before his publicist chimes in to keep us on topic and on schedule.

“So it’s a big night,” he says. “It’s going to be a lot of Jelly happening, man. Even if I lose, they still got to hear my name called five times. [Laughs] We won being here, dude. The fact that we’re in the building was a win.”

“Nashville! I only got a second, and I’m gonna say a lot.”

That’s how DeFord opened his emotional one-minute speech accepting the New Artist of the Year trophy on Nov. 8. Beyond his show-opening performance with Wynonna Judd, who sounded incredible but looked like she needed a great big hug, DeFord would sing twice more, once with K. Michelle and once in the final performance. His “Save Me” duet partner Lainey Wilson took home the big trophy (Entertainer of the Year), but the hometown homeboy would not leave empty-handed. A long and winding journey from juvenile offender to unlikely country star culminated with DeFord onstage, surrounded by his team, clutching his trophy.

“There is something poetic about a 39-year-old man winning new artist of the year,” DeFord declared from the Bridgestone stage, just a short distance from Demonbreun Street — where he once spent so much time putting flyers in hands. “I don’t know where you’re at in your life or what you’re going through, but I want to tell you to keep going, baby. I want to tell you success is on the other side of it. I want to tell you it’s gonna be OK. … What’s in front of you is so much more important than what’s behind you.”

As he speaks, you can hear the adrenaline in his voice, pumping up each phrase with revival-preacher energy until it feels like the whole room is ready to explode. All of the hustle and hard work, from selling CD-Rs to conquering country radio, nearly two-and-a-half decades of forward momentum, has been building toward this moment.

“Let’s party, Nashville!”