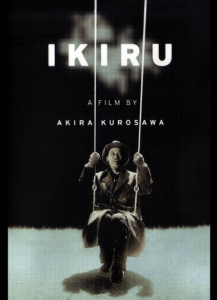

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952)

This blog is conversation 1, part 1 of a series about wellness and films. This blog, the first of two parts, explores spiritual wellness.

By Erika Ihara and Kei Okada, M.Div., BCC, Program Manager, End-of-Life Spiritual Care, Visiting Nurse Service of New York, Hospice and Palliative Care

“What have I been living for all these years?” Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952)

Erika: What is spiritual care and, in your experience as a chaplain, how does spiritual wellness relate to other dimensions of wellness and/or health?

Kei: Dame Cicely Saunders, who founded the hospice movement and envisioned a compassionate and holistic discipline of palliative care, termed suffering as “total pain”—physical, social, psychological, and spiritual pain. Based on her vision, spiritual care supports spiritual, existential, and religious aspects of our patients’ and their families’ well-being, in collaboration with our inter-disciplinary hospice-care team. Spiritual care develops individualized care plans as part of the team’s care plan, assessing and promoting the terminally ill person’s quality of life, and treating each person with compassion, dignity, and respect.

Spiritual care offers a safe, non-judgmental space and time for self-reflection, expression, and exploration to empower people to own their living process. Instead of trying to “fix problems” or to “give answers,” we validate all that they go through and support their search for and experience of life’s new meanings, potential, and hopes, honoring their daily accomplishments.

Erika: You lead the program at Visiting Nurse Service of New York for end-of-life spiritual care for individuals who may also be receiving care for physical or mental illness. What’s an example of how you engage in interdisciplinary work with medical clinicians to support a multifaceted understanding of wellness and end-of-life care?

Kei: Upon each patient’s admission to our service, the medical team works on alleviating physical pain or discomfort first, as soon as possible. Unless physical pain and suffering are contained, the person may not be able to feel or think well. Hospice admission itself is overwhelming or unreal for many, so it is important for the hospice care team to help reframe their mindset from “there is nothing medicine can do (there is no cure)” to “there are many (different) things we can do,” empowering and integrating the patient and family into the team to work on improving their quality of life.

Since physical, social (relational, financial), and psychological (mental) distress affects spiritual well-being and vice versa, it is important for spiritual care to assess how these dimensions of experience are affecting the person’s overall comfort, well-being, and decision-making. That’s how team collaboration becomes crucial. A patient’s physical pain and symptoms may be a nurse’s question of which medication works best; a social worker may assess any possible psychosomatic source of pain, history of any mental illness or depression, or relational and financial concerns from a psychotherapeutic approach; whereas a spiritual care counselor may assess any personal, social, cultural or religious values or beliefs as a potential source of meaning or hope to transcend the current suffering, in relationship with whatever is beyond oneself, in the transformative exploration of life’s meaning and potential. Life review can become a meaningful process of self-discovery in relationships with self, others, loved ones, nature, universe, God, or the sacred. And as requested, we offer prayers and blessings to enhance their sense of spiritual wellness.

One may say “I feel depressed” and reveals that he has been living with depression for many years and a certain medication used to work. Now he is taking a new medication and he doesn’t think it is working for him. In this case, our team’s doctor and nurse will discuss with the patient’s doctor and adjust medications. The other patient says the same thing, but she has never felt depressed in her life. She has always been a positive and cheerful person and feeling depressed makes her feel lost. She says, “This is not me. Who am I now?” In this case, a spiritual care counselor may facilitate her exploring the root causes of her distress beyond any diagnosis and what may be possible beyond the current perception of suffering.

End-of-life is a sacred season of life, a spiritual process of living with full awareness of mortality. Spiritual care witnesses and affirms without judgment how spiritual experiences of mystery, such as seeing or talking with deceased loved ones, also can be meaningful. This is how our hospice team support becomes holistic: to support the full scope of human experience in order not to medicalize our humanity.