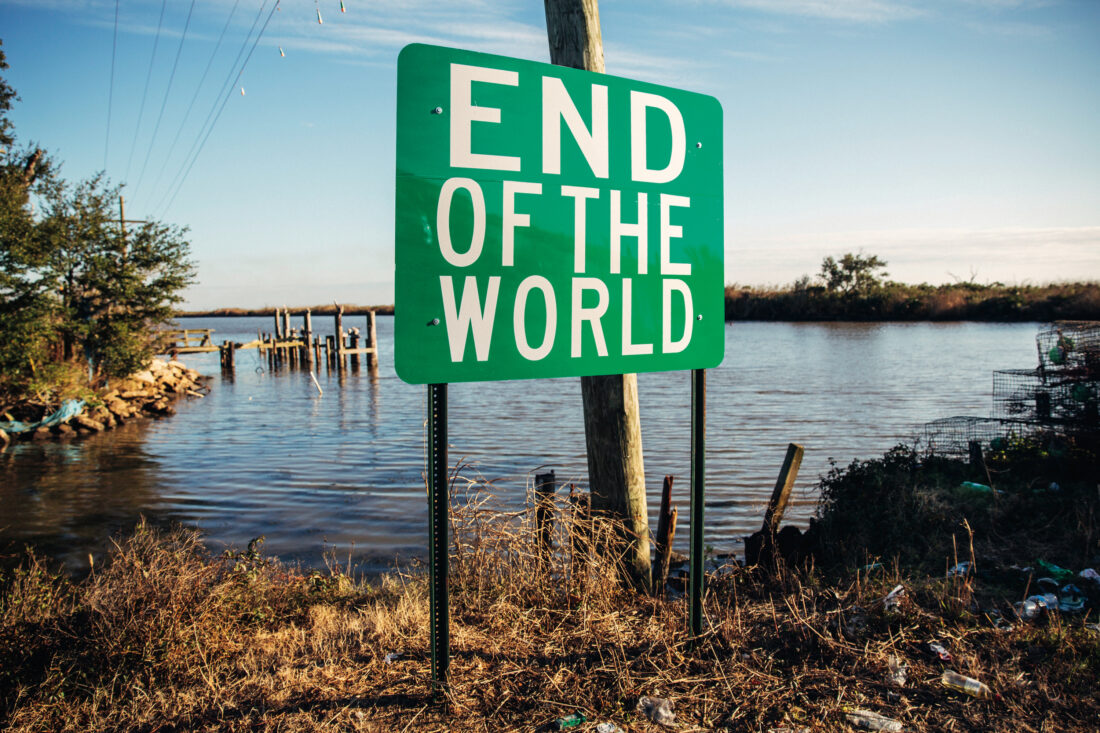

Shell Beach is about a forty-minute drive from my home in New Orleans. It’s not really a beach nor does it have much in the way of shells, but it’s where fishermen slap their rods at the water and where kayakers like me can launch to paddle across a canal into a deep fringe of marsh. From here we follow an old river course through the grasses to Lake Borgne, which isn’t really a lake but an inlet from the Gulf of Mexico.

What the area does have is the foreboding relic of Fort Proctor, an impressive brick fortification built between 1856 and 1859 and now sinking and surrounded by water nearly a mile offshore. I paddled out early one recent morning as a wispy mist scudded along the water; the air was filled with the smell of decay familiar to anyone who’s traveled along a low-tide marsh. I could see the fort’s crenellated roofline rising over the grasses and mist as I set off, but it soon vanished from view as I entered deeper into the realm of blackbirds.

Proctor was one outpost of nearly four dozen fortresses built over the decades to defend important cities by the nation’s coastlines from invasion. President James Monroe hailed the creation of this defensive network in his second inaugural address in 1821, noting that it would keep ships of ill intent from venturing too close, and as a result the government would “be protected from insult.”

The logic of building a fort along a lake surrounded by marshes about thirty miles from a city may seem elusive, but this spot happens to be close to where the British landed when they tried to invade New Orleans during the War of 1812. If nothing else, humans are very good at fighting the last war.

It was originally constructed about 150 feet back from the shoreline, but over time hurricanes ate away at the land. Behind the fort, a five-hundred-foot-wide navigation canal decisively severed it from land in the 1960s. Today it’s essentially a crumbling island redoubt, accessible only by boat.

When I need to clear out of New Orleans for a few hours to empty my head, I basically have two choices: swamp or marsh. The swamp can be lovely, although it often feels filled with menace, for the simple reason that it actually is filled with menace. I’ll see black snakes in trees and alligators with unblinking eyes on low embankments, all surrounded by a sort of fractal landscape free of landmarks that makes it all but impossible to remember which way I came in and which way I should go out. There’s also the Spanish moss draped from cypress limbs. This has been romanticized by writers and filmmakers, but when I’m disoriented in the swamp, I start to think of these moss-covered branches as the tentacles extending from something alive and malevolent.

A marsh is the opposite of a swamp: It’s all open views and soothing rustling sounds. It’s an edge rather than a dark center. Here, I always seem to be on the cusp of clearing the grasses and finding myself amid the glare and glint of open waters and the prospect of a limitless future. Swamps are for brooding about the past; marshes are for building tomorrow’s daydreams.

By the time I made my way through the marsh grass, the mist had largely burned off. After a last bend, the fort rose in front of me. It’s called a fort on the maps and in the books, although it has also been characterized as a martello tower, which is a more specialized type of fortification. It’s definitely not a castle, even though some insist on referring to it as Beauregard’s Castle, since P. G. T. Beauregard—the general who started the Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina—worked on its innovative design.

The fort is square and runs sixty-eight feet on each side, and when first built, its walls of brick and concrete stood almost thirty feet high. A classic Georgian-style pediment at the entrance makes it seem serious. It’s a bit medieval looking and has narrow loophole windows from which to fire upon attackers, along with those crenellations along the top. I posted a picture on Instagram once and a friend immediately texted to ask if I was in Scotland.

The National Park Service has called it “one of the finest examples of the Third System of U.S. Fortifications,” varieties of which were built all the way to Maine. At least this was a fine example. Some of the taller towers have toppled, and winds and waves have swept away much of the mortar between the bricks. Around the entryway, bricks have fallen out of the wall, bringing to mind a piano with missing keys.

I beached my kayak in a small cove a few dozen yards from the entrance and made my way through marsh grass and southern dewberry, then inched along a narrow granite ledge running along the foundation to avoid ankle-deep water obscuring calf-deep mud at the fort’s threshold. The exterior maintains a vaguely regal if aging aspect, but inside it’s pure dystopian chaos. Haphazardly tumbled towers the size of garden sheds lay about, and the rusting iron beams above seem to remain elevated only owing to some obscure sense of loyalty. The floor is mostly pooled water and mud, some dense enough to stand upon but much of it greedy and eager to suck shoes from the unwary. Adding to the chaos is wild-eyed graffiti, including one colorful painting depicting an alien, its arms outstretched as if on a crucifix.

The fort was built to repel an enemy who never came, but it was never finished and never garrisoned. A hurricane in 1859 halted work, and then the Civil War erupted, and construction stopped for good. Anyway, Fort Proctor was obsolete by the time it went up, and had it come to blows, new and improved artillery then available would have reduced it to rubble in short order.

My first trip out to the fort happened during the early days of the pandemic. It was a place of extreme isolation, a space to sequester myself from an unseen enemy. It felt oddly protective and safe then. Today the fort is fighting another stealthy but unseen enemy. Waters are rising, marshes are disappearing, and the fort is sinking. The coast is retreating (I read one report that Louisiana has lost a quarter of its wetlands—an area approximately the size of Delaware—since the 1930s), and today the fort is making a heroic last stand against climate change, but with a future that seems sadly foreordained.

When I paddled back an hour later, the landscape was silent save for the clumsy thump-thump of cormorants straining their way up into the air, and the occasional tearing-silk sound of blue herons lifting off effortlessly. As I wove back through the marsh, it occurred to me that I was returning from what academics like to call a liminal space—a space that’s neither here nor there, but someplace that exists in between. The fort exists on neither land nor water, and in neither past nor present, but occupies a tenuous place in each. Which, it should be said, makes it an ideal foundation for building castles of the mind.