Earlier this month, a former candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives sent a tweet implying that President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda was causing grocery shelves to empty.

There were a couple of things wrong with the tweet, which has been deleted. The first is that the photo was taken in March 2020, before Biden took office. And if you take a closer look at the prices? Those are British pounds, not U.S. dollars. The photo, PolitiFact noted, was taken in Worcester, England, and originally published alongside an editorial in the Guardian about early-pandemic supply chain woes. (It’s also, incidentally, one of the first hits when searching Google Images for “empty shelves.”)

There were a couple of things wrong with the tweet, which has been deleted. The first is that the photo was taken in March 2020, before Biden took office. And if you take a closer look at the prices? Those are British pounds, not U.S. dollars. The photo, PolitiFact noted, was taken in Worcester, England, and originally published alongside an editorial in the Guardian about early-pandemic supply chain woes. (It’s also, incidentally, one of the first hits when searching Google Images for “empty shelves.”)

Between the incorrect currency and the use of “veg” as a noun, Twitter users were quick to realize the photo was misleading. It’s not the first time an out-of-context photo has been repurposed to fit a political narrative and given how cheap and effective the misinformation tactic can be, it certainly won’t be the last. The problem is that they’re not all as obvious as the U.K. example.

What if news consumers could see relevant information about a digital photo — like where and when it was taken, and by whom — without having to click away or sort through reverse image search results? Would that allow them to make better decisions about who to trust online? Be more resistant to misinformation? Increase their confidence in participating newsrooms? Working with a large, international consortium, Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) has spent two years trying to answer these questions.CAI is developing tools and standards that allow people to capture, store, and verify key details about a photo — its digital provenance — with an eye toward creating standards that can be used across the internet. Last week, Adobe announced that anyone with Photoshop can opt-in to creating content credentials on their work and said it would update its Verify web application so that anyone can view the digital provenance of a supported image.

Want to see what it might look like in practice? Here’s an screenshot from “78 Days,” an application of CAI work from Reuters, Project Starling, and the blockchain startup Numbers. Users can click on the “i” icon to see details about who produced the content.

Andy Parsons, director of CAI at Adobe, expects the open-source specifications to be released in early 2022.

“Provenance, effectively, is an alternative and a complementary method for combating misinformation in the journalism space, where instead of detecting what may be fake photos that have been modified, videos that have been modified, synthetic actors or objects that have been asserted or removed, or what have you, we’re after something called provenance: the provable, verifiable ground truth about how something was created,” Parsons said. “What Adobe will do going forward, particularly for journalists and organizations interested in implementing content provenance, is build a specification into our tooling, and then open-source that tooling so it’s available to anyone — unencumbered with any sort of licensing of any kind. That’s the path forward.”

It might take a bit before this is useful to you. I couldn’t get a single photo to show content credentials — not photos from the group’s founding partner The New York Times nor images from the BBC. Not the image for the out-of-context Guardian photo. Not images from Adobe Stock or Adobe-owned Behance. I couldn’t even find the credentials — seen above — that appeared in the Reuters project. (Parsons, in response, said the older examples are not compatible but that images exported in Photoshop starting with the announcement last week should show up, as long as the creator has opted-in. Journalists working with anonymous sources or under unfriendly governments may, of course, have reason to remain opted-out.)

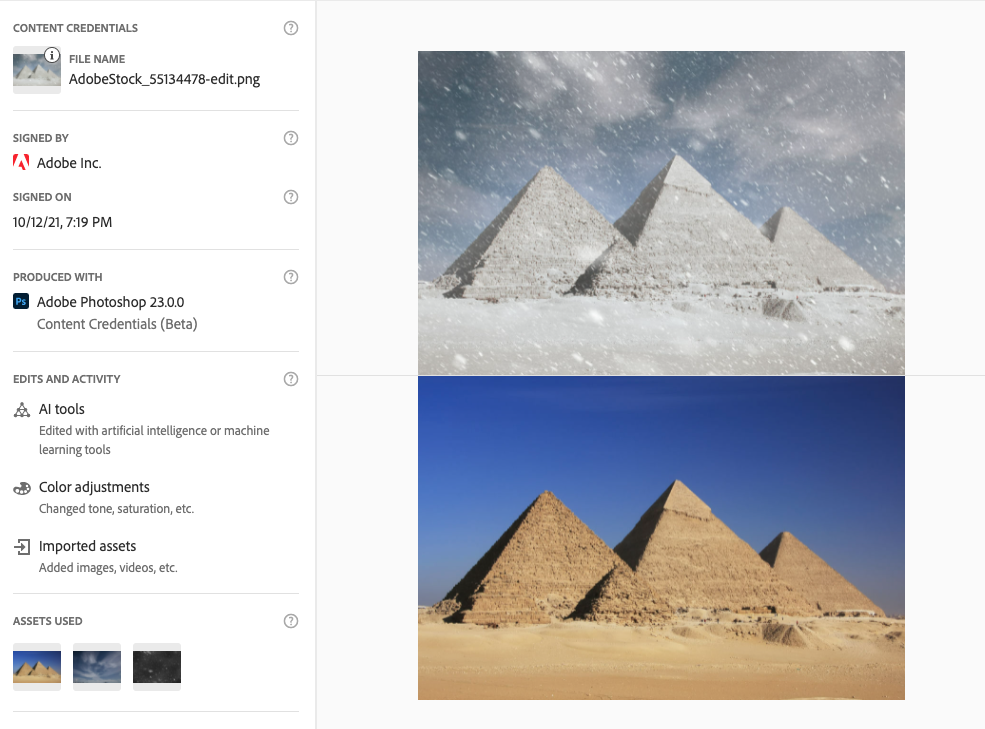

But if you want to see how it could work, there’s an example on the site. You can, obviously, change a lot about a photo in Photoshop. New neural filters, for instance, allow users to change a verdant, summery landscape into a bare winter scene using a slider tool and images can be combined and remixed. Inspect this image depicting snow-covered pyramids in Egypt, for example, and you can see it was edited in Photoshop and that other assets (in this case, Adobe Stock photos of driving snow and a cloudy sky) were added to the original file.

The applications go beyond journalism and fighting misinformation for Adobe. The company’s chief product officer, Scott Belsky, introduced content credentials as a way for people to ensure they get credit for their creative work at Adobe’s annual conference on Tuesday and spoke at length about its NFT applications with The Verge.

Moving forward, Adobe will continue working with Twitter — an early partner for C2PA in developing cross-industry standards — and other platforms to work toward displaying content credentials in a way that news consumers can recognize.

“It’s a little too early to tell the shape that this will ultimately take for Twitter users. but certainly Twitter is committed to the idea of provenance,” Parsons said. “We want to be sure that the provenance indicator — like the ‘i’ icon [in the Reuters project] — is internationally recognizable, something that has meaning across cultures but also is distinctive. I sometimes use the metaphor of the lock in the browser, which has become ubiquitous. No one would even think about sending their credit card or personal information to a website without the lock. The lock provides some assurances about security in the same way that we want the icon that we ultimately decide to use universally to represent trust and transparency for media. The ‘i’ is a placeholder, but that’s the goal.”

Current CAI members include AFP, the BBC, CBC, Gannett, The New York Times, McClatchy, The Washington Post, and more. Parsons said news organizations among their membership are moving toward implementing digital provenance in their products and that the timeline ranges from a few months to a few years. Many are waiting on the open standard specifications that will be released early next year. If you’re reading this from a newsroom without the resources of a New York Times, fret not. The CAI is actively looking for more news organizations to partner with — and is especially interested in getting feedback from smaller outlets and ones outside North America and Europe. You can fill out a membership form here.