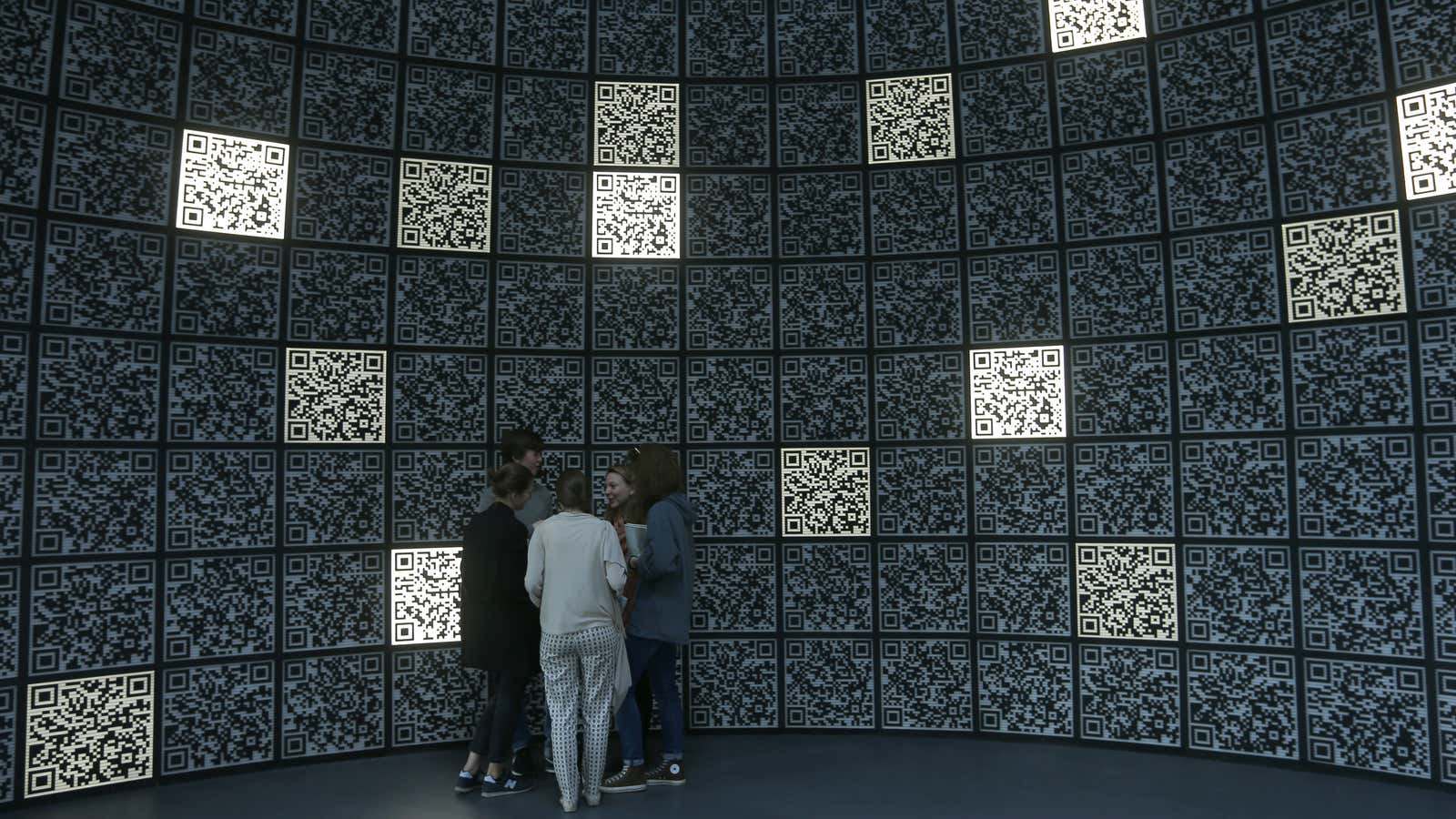

There’s a new front in the war between food companies and consumer advocates over food labeling: QR codes.

Under growing pressure to disclose exactly what goes into the food we buy and how it’s produced, big food companies in the US have come up with a clever solution. Rather than print food information directly on product packaging, they’re proposing to stick a lot of it behind QR codes consumers scan with their smartphones that link to online product pages. So while the Nutrition Facts Panel and allergen information required by regulators would remain on-package, information about genetic modification and food processing facilities are just two that would migrate online.

The Grocery Manufacturers Association (or GMA, which represents big players including Unilever, Pepsico, The Coca-Cola Company and Nestlé) lobbied hard to have those digital tools included in a GMO labeling bill making its way through Congress. This week, (July 12) global beer companies announced they are considering adopting the technology to voluntarily disclose caloric and ingredient information about their products.

Companies say their online information repository—which the GMA is calling the SmartLabel program—will save money on redesigning physical packages for each new disclosure demanded by consumers. Public health groups say it’s a clever tactic to avoid more upfront labeling, since QR codes aren’t nearly as accessible as reading the physical label.

QR codes are a black hole

Accessing QR codes is even more difficult for consumers who don’t own smartphones, health advocates say, and Pew Research Center data show more than one-third of Americans didn’t own a smartphone in 2015.

The program could also discriminate against poor consumers and minorities. Nearly a quarter of smartphone owners in 2015 had to cancel or suspend their service because of financial constraints.

A study (pdf) commissioned by health advocates—including the Center for Food Safety, Citizens for Health, and the Union of Concerned Scientists— surveyed 800 likely 2016 general election voters and found 83% of people had never scanned a QR code.

For its part, GMA says there will be alternatives to the QR code, including listing 1-800 phone numbers and web addresses on packaging, or even in-store Google searching. But those options may not appeal to already harried consumers like parents with children, who don’t have time to scan multiple brands or dial 1-800 numbers on their grocery run.

“This is really a way of putting more and more distance between the consumer and the information they need to know,” said Andrew Kimbrell, director of Center for Food Safety. “This is non-labeling hiding as labeling. It’s really easy to label—just put it on the label.”

The GMA provided research arguing that QR codes aren’t dying, and that their slowing growth is typical of a maturing technology. A spokesperson for the Beer Institute said it did not have such data available.

Jim Flannery, head of operations for the GMA, explained that most consumers research and learn about food outside the store, and information-hungry food consumers tend to be tech-savvy. Physical space on packages is also precious real estate, and largely devoted to marketing the product.

“Consumers want so much more information than could ever fit on a package,” said GMA spokesman Roger Lowe. “Digital is the only way to go.”