Rudy Pyatt, the first Black reporter hired by a major newspaper in Charleston who went on to a distinguished career in journalism, died Jan. 7 in a Maryland hospital. He was 88.

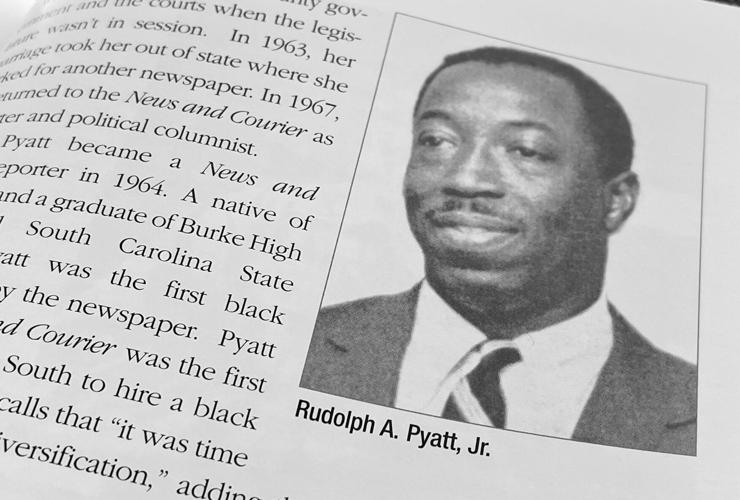

A graduate of Burke High School and S.C. State College, Pyatt served in the Army and then tried to find a journalism job, but racism and discrimination blocked his way. He taught English and journalism at C.A. Brown High School, where he also advised students working on the school newspaper.

The students’ work won some awards, garnering attention from editors at The News and Courier.

In the summer of 1964, he joined the Charleston paper on a part-time basis. After his summer stint, editors offered him a full-time job.

He was among an early cadre of young Black reporters breaking barriers in the South. His work on the police beat earned him a reputation for fairness and thoroughness, according to an account published in the book "Pages of History: 200 Years of The Post and Courier." Colleagues remained aloof at first, but the sportswriters were welcoming and helped Pyatt settle in. Pyatt was a sports enthusiast who had been a track star in college.

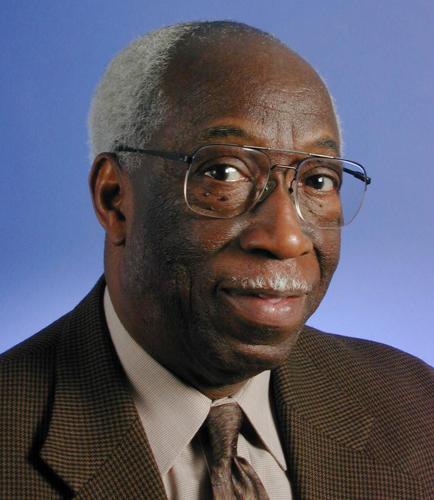

Washington Post financial columnist Rudolph A. Pyatt Jr. Pyatt's first regular journalism job was at The News and Courier in Charleston. Washington Post/Provided

In 1968, the newspaper expanded its coverage of national politics and sent Pyatt to Washington, D.C. Not long after, he left the paper and joined the public TV station WETA, according to a Jan. 13 obituary in The Washington Post. He went on to work for the D.C. public schools and as a political consultant before returning to journalism.

First, he worked at The Washington Star, then The Washington Post starting in 1981. At The Post, Pyatt covered business, real estate, economic development and local government, contributing a business column during the last phase of his career there.

At the start of his career, he found himself straddling two eras, that of Jim Crow and that of a newly desegregated America. At the end of his career, he was once again caught between eras, taking note in his columns of global economic trends that impacted local businesses.

“The old establishment (a close-knit, conservative fraternity) has given way to a new order of corporate princes and princesses, wielding power and influence and flaunting newfound wealth from the headquarters of Internet and telecommunications companies, highly paid consultants’ offices, and, yes, law firms and real estate developers,” he wrote in his farewell column for The Post, quoted in the newspaper’s obituary.

Rudolph Augustus Pyatt Jr. was born in Charleston on Jan. 15, 1933, to a tailor and a teacher.

At S.C. State, a historically Black school, he was involved in the 1955-56 student uprising, which began as a protest of segregation in Orangeburg but morphed into a campaign to oust the school's president, Benner C. Turner.

Students felt that Turner was a puppet of the all-White board of trustees and a vindictive autocrat who could not tolerate dissent, according to William Hine, author of “South Carolina State University: A Black Land-Grant College in Jim Crow America,” a book-length history of the school.

“Students had no rights,” said Hine, who began his career as a history professor at S.C. State in 1967 and who got to know Pyatt personally. “There was no due process, there were no hearings.”

So they boycotted classes over several months and publicized their concerns widely.

Pyatt had written for the campus newspaper, The Collegiate, and engaged in a dispute with former student body president Benjamin Payton. Turner objected, firing the faculty adviser to the paper, Florence Miller, who subsequently sued and settled.

As the protests turned into boycotts, “Pyatt was a key participant and enthusiastic supporter.”

Turner moved to suspend student leaders of the unrest, including Fred Moore, a James Island native who served as student body president after Payton and during the period of rebellion.

Turner wanted to kick out Pyatt, too, but the young man was in ROTC and to be commissioned as a second lieutenant, “so it was too risky,” Hine said. “In retribution, Turner went after his sister (Alice), who had not been very involved.”

In 2006, the school hosted a 50th reunion, attended by Pyatt, and issued an apology to the students affected by the unrest.

“The last time I saw him was in 2016, in Washington,” Hine said. “I could tell he was beginning to suffer from dementia. He was a little forgetful, until I mentioned Turner. Then he perked up.”

In his farewell Post column, Pyatt reflected on his journalistic beginnings.

“It was the fulfillment of a boyhood dream that had been deferred by the South’s long and stubborn embrace of segregation and by the newspaper industry’s hypocrisy and duplicity about race,” he wrote.

He would go on to find success in the field he loved, first in Charleston, then in the nation’s capital.

Pyatt is survived by his wife, Jacqueline Bell Pyatt of Fort Washington, Md.; sons, Rudy Pyatt of Brooklyn, N.Y., and Randy Pyatt; sisters, Alice A. Pyatt of Charleston and Gwendolyn Marion of St. Albans, N.Y.; and two grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at noon Jan. 22 at Carolina Memorial Gardens, 7113 Rivers Ave., North Charleston.