Cardiology

‘BEG’ Diets and DCM in Dogs: Recommendations Regarding Diagnosis and Management

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in dogs is a primary myocardial disease characterized by enlargement and decreased function of one or both ventricles. The disease is progressive, resulting in worsening cardiac function, heart enlargement, and ultimately congestive heart failure. Other complications include arrhythmias, syncope, and/or sudden death.

The classic form of DCM in dogs is naturally occurring and heritable, most commonly observed in breeds such as Doberman Pinschers, Great Danes, and Irish Wolfhounds. Patients with this form of the disease are said to have ‘primary’ or ‘idiopathic’ DCM. Some other causes of DCM include infectious/inflammatory processes (such as myocarditis), nutritional causes (such as taurine deficiency), and tachycardia induced DCM (secondary to persistent tachyarrhythmias).

While idiopathic DCM is the most commonly observed form, the other causes are important to keep in mind and identify. Many cases of nutritionally induced DCM can be reversed if the nutritional deficiency is identified and treated. Similarly, patients with tachycardia induced DCM can show full reversal of the cardiac changes once the underlying arrhythmia has been treated and controlled.

Recently, the focus has shifted to an association between grain-free diets and the development of DCM in our canine patients. More specifically, the implicated diets are collectively referred to as ‘BEG diets’ from Boutique companies, contain Exotic ingredients, and many are labeled as Grain-free. Veterinary cardiologists across the country have been diagnosing increased rates of DCM in dogs eating these diets, with many dogs showing improvement when the diet is changed. This recent association has resulted in many concerned owners and veterinarians alike.

The FDA Investigation

In July of 2018, the FDA announced it had begun investigating reports of DCM in dogs eating certain diets. Many of the implicated diets were labeled as ‘grain-free’, and contained peas, lentils, other legume seeds, and/or potatoes.

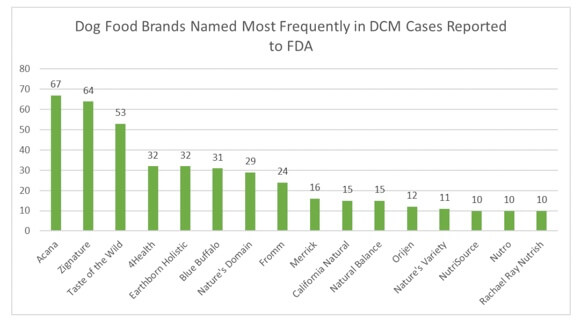

An update on the investigation was released in June 2019. This update detailed 574 reported cases of DCM between January 2014 and April 2019 (560 dogs and 14 cats). The reported cases included a wide range of breeds, many without a genetic predisposition to developing DCM. Some of the cases showed evidence of low blood taurine levels, while others had normal or high blood taurine levels. Of the reported cases, more than 90% of the diets were labeled as ‘grain-free’, and 93% of the diets contained peas and/or lentils as a main ingredient. A much smaller proportion of diets contained potatoes. Many of the pets were fed exclusively dry food (86%), with smaller numbers eating wet/dry combinations, raw diets, or homecooked diets. The animal protein sources in the diets varied greatly. A list of the most frequently named dog food brands in the reported cases can be observed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Dog food brands named most frequently in DCM cases reported to the FDA

The FDA and the Veterinary Laboratory Investigation and Response Network (Vet-LIRN) have evaluated and analyzed many of the implicated diets. Thus far no abnormalities have been detected. The FDA and Vet-LIRN are also collaborating with veterinary cardiologists to gather prospective data on affected dogs, and gain more information regarding response to treatment over time and long-term prognosis. A full summary of the June 2019 update is available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/news-events/fda-investigation-potential-link-between-certain-diets-and-canine-dilated-cardiomyopathy.

Recommendations Regarding Diagnosis and Management

Taurine Testing and Supplementation in Dogs

Taurine testing is generally recommended for any dog diagnosed with DCM that is eating a BEG diet. Ideally, both whole blood and plasma taurine levels would be tested. Whole blood taurine levels are preferred as they better represent long-term taurine status. Low blood taurine levels support a diagnosis of diet-associated DCM, and taurine supplementation is critical in these patients (in addition to a diet change). Normal or high blood taurine levels do not eliminate the potential for diet-associated DCM, as a majority of affected dogs have normal or high blood taurine levels. Taurine supplementation should still be considered in these cases (in addition to a diet change), as taurine is well tolerated and may provide additional benefits for cardiac health and function. The current recommended dosing for taurine is as follows: 250 mg, PO, every 12 hours for dogs weighing < 10 kg (22 lb.); 500 mg, PO, every 12 hours for dogs weighing 10 to 25 kg (55 lb.); and 1,000 mg, PO, every 12 hours for dogs weighing > 25 kg.

Taurine testing should not be utilized as a screening tool in dogs eating a BEG diet that could be at risk for DCM. A low blood taurine level in this situation would certainly raise concern for underlying DCM. However, a normal or high blood taurine level would not eliminate the possibility for DCM in that patient.

Continuing to feed a BEG diet, but simply supplement additional taurine into the diet. This is not recommended, as many affected dogs have normal blood taurine levels at the time of diagnosis, and none of the implicated diets have been shown to be taurine deficient. Additionally, many affected dogs have been shown to improve with diet change alone, indicating the underlying problem does not appear to be solely taurine deficiency. Recent data suggests that for most breeds, taurine may not play a significant role in the recent dietary DCM issues. However, some breeds, such Golden retrievers, may be more susceptible to taurine deficiency when fed suspect diets.

Diet Recommendations for Dogs

A diet change is recommended for any dog diagnosed with DCM and that is eating a BEG, vegetarian, vegan, or home-prepared diet. Ideally, clients should choose a diet that is manufactured by a well-established company following the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Global Nutrition Committee Guidelines. Diets labeled as grain-free should be avoided. If legumes are included in the ingredient list, they should appear low on the list; below all meat and grain content. The undesirable ingredients should not be in the top 5 to 10 ingredients, though this alone still may not be protective.

In regard to recommending a diet change for any dogs without known heart disease eating a BEG diet – this is more difficult. We know many dogs have eaten BEG diets for numerous years and have never developed heart disease. Alternatively, we also know some dogs have developed life-threatening heart disease while eating these diets, with their hearts showing improvement once the diet was changed. This leaves owners and veterinarians in a conundrum. Certainly not every dog eating a BEG diet will develop heart disease; but at this stage we have little data to determine which dogs are at risk. Given the uncertainty, we currently recommend all owners avoid feeding BEG diets, if possible. In patients that have specific dietary restrictions and needs, a veterinary nutritionist and the primary veterinarian should be consulted regarding alternative diet options.

Some owners have opted to continue feeding a BEG diet, but simply supplement grain into the diet. This is not recommended. There has been no conclusive evidence to suggest the lack of grain content itself is responsible for the development of DCM. Rather, the issue may be with ingredients utilized instead of grains; such as peas, lentils, potatoes, and other legumes.

Screening Tests?

Any dog eating a BEG diet that develops clinical signs or symptoms of heart disease such as a heart murmur, arrhythmia, syncope, exercise intolerance, coughing, or difficulty breathing should undergo evaluation by a veterinary cardiologist, if possible. DCM is best diagnosed via echocardiography, and early identification improves the chances of a positive outcome.

What about dogs that are eating a BEG diet but have no clinical signs or symptoms of heart disease? If the owners are highly motivated, a screening echocardiogram could be considered. If the owners are hesitant to pursue a full evaluation with a cardiologist, but are inclined to have some screening tests performed, thoracic radiographs and/or an NT-proBNP can be considered. If the heart is unremarkable on thoracic radiographs and an NT-proBNP is normal, concern for underlying DCM decreases. Alternatively, if there is evidence of heart enlargement on radiographs or an NT-proBNP is elevated, further evaluation with a cardiologist is indicated. If the owners are reluctant to pursue any additional diagnostics, a diet change and close monitoring for any symptoms of heart disease is reasonable.

Prognosis for Affected Dogs?

A majority of dogs diagnosed with diet-associated DCM will show improvement over time if they are transitioned to an appropriate diet (+/- taurine supplementation). This appears to be especially true for dogs that are diagnosed early in the disease process. It is currently challenging to determine if we can expect a complete recovery or only partial recovery in these cases. Many dogs diagnosed with mild/early changes seem to make a complete recovery after a diet change, while some dogs with more severe disease at the time of diagnosis show only partial recovery. The improvement can typically be seen over a period of 3-6 months, or even longer in some cases. Ongoing research and data collection will allow us to better determine the long-term prognosis for affected patients.

It is also important to remember that some patients may truly have idiopathic or heritable DCM. This is especially true in patients such as Doberman Pinschers, Great Danes, and other breeds genetically prone to developing the disease. If these patients are eating a BEG diet and are diagnosed with DCM, we still recommend a diet change and taurine supplementation. However, it is also important to caution the owners there may be no improvement with these changes.

References

- Adin D, DeFrancesco TC, Keene B, Tou S, Meurs K, Atkins C, Aona B, Kurtz K, Barron L, Saker K. Echocardiographic phenotype of canine dilated cardiomyopathy differs based on diet type. J Vet Cardiol. 2019 Feb;21:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2018.11.002. Epub 2018 Dec 5.

- Freeman LM. A broken heart: risk of heart disease in boutique or grain-free diets and exotic ingredients. Jun 4, 2018. Available at: http://vetnutrition.tufts.edu/2018/06/a-broken-heart-risk-of-heart-disease-in-boutique-or-grain-free-diets-and-exotic-ingredients/.

- Freeman LM. Diet-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM): Update, July 2019. July 17, 2019. Available at: https://vetnutrition.tufts.edu/2019/07/dcmupdate/.

- Freeman LM, Stern JA, Fries R, Adin DB, Rush JE. Diet-associated dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs: what do we know? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018 Dec 1;253(11):1390-1394. doi: 10.2460/javma.253.11.1390.

- Freeman LM. It’s Not Just Grain-Free: An Update on Diet-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Nov 29, 2018. Available at: https://vetnutrition.tufts.edu/2018/11/dcm-update/.

- Kaplan JL, Stern JA, Fascetti AJ, Larsen JA, Skolnik H, Peddle GD, Kienle RD, Waxman A, Cocchiaro M, Gunther-Harrington CT, Klose T, LaFauci K, Lefbom B, Machen Lamy M, Malakoff R, Nishimura S, Oldach M, Rosenthal S, Stauthammer C, O’Sullivan L, Visser LC, Williams R, Ontiveros E. Taurine deficiency and dilated cardiomyopathy in golden retrievers fed commercial diets. PLoS One. 2018 Dec 13;13(12):e0209112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209112. eCollection 2018.

- US FDA. FDA investigating potential connections between diet and cases of canine heart disease. Jul 12, 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/cvm-updates/fda-investigating-potential-connection-between-diet-and-cases-canine-heart-disease.

- US FDA. FDA Provides Update on Investigation into Potential Connection Between Certain Diets and Cases of Canine Heart Disease. Feb 19, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/cvm-updates/fda-provides-update-investigation-potential-connection-between-certain-diets-and-cases-canine-heart.

- US FDA. FDA Investigation into Potential Link between Certain Diets and Canine Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Jun 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/news-events/fda-investigation-potential-link-between-certain-diets-and-canine-dilated-cardiomyopathy.

- US FDA. Vet-LIRN Update on Investigation into Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Jun 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/science-research/vet-lirn-update-investigation-dilated-cardiomyopathy.

- World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Global nutrition guidelines. Available at: www.wsava.org/Guidelines/Global-Nutrition-Guidelines.