It began simply enough. In 2016, Naz Georgas, a Muslim woman, took a cab to East End Temple, a Reform synagogue near Union Square in New York City.

The reason for her visit was to ask the synagogue leadership whether her organization could use space in their building. She was starting a new, pluralistic approach to teaching Muslim children, but she needed a place to gather.

She still remembers the ride.

“I was apprehensive,” she said. “What would I say to the rabbi? I remember thinking, ‘God, make this easy for me.’”

She had little to be apprehensive about.

With the blessing of the synagogue’s interim rabbi, Georgas began leading youth in religious education classes every Sunday at East End Temple, which is home to a congregation of about 350 families.

The synagogue had a long-standing commitment to social justice and what its current rabbi, Joshua Stanton, describes as a “willingness … to be vulnerable and get to know people.”

That openness to others, that vulnerability, has led to a remarkable interfaith relationship with Georgas’ organization, which is called Cordoba House.

At first, the relationship was a simple space-rental agreement. But over the years, it developed into a deep connection between the two communities that grew to include adult learning, worship and activism -- particularly around the issue of immigration.

This type of relationship is “not for the faint of heart,” Stanton said. ”Building deep relationships with another religious community … requires vulnerability, acknowledging that you don’t have all the answers or even close to all of them, and working to see the world through the lens of their community members.”

From controversy to community

In 2013, a Muslim interfaith group known as The Cordoba Initiative (TCI) hired Georgas as its faith and community affairs director. In the wake of a failed attempt to build a community center and mosque a couple of blocks from the World Trade Center site, TCI needed to rethink how to move forward.

Georgas’ goal was to build an American Muslim community of leaders and educators that taught universal values and would help Muslims develop a better understanding of what it means to practice Islam in America.

Born in Bangladesh to a diplomatic family, she spent her youth in a wide range of countries -- Kuwait, Egypt, Bangladesh, France, Japan, Australia. She ended up in New York for graduate work at Columbia University.

She calls herself a “global citizen,” which posed challenges for her as a Muslim seeking to practice her faith and join a house of worship.

What experience have you had developing interfaith relationships? When has that been life-giving to you and your organization? When has that been more difficult?

Many mosques teach religion in a way that is shaped by culture and “focused more on rules and regulations,” she said. She wanted something different for herself and her young children. She wanted a community and religious education that focused on deepening her spirituality and placed more emphasis on universal values.

In 2015, she started Cordoba House as a separate entity to create and run the new education programs she had developed in conjunction with Jewish and Presbyterian educators. Rebekah Hutto, then an associate at the Brick Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, who shared lesson plan templates and activities.

Rather than focus on building a physical space, Georgas wanted to “build more lasting communities through regular education based on enhancing our core values of pluralism, [with] compassion being the core of religious doctrine and spirituality,” she said.

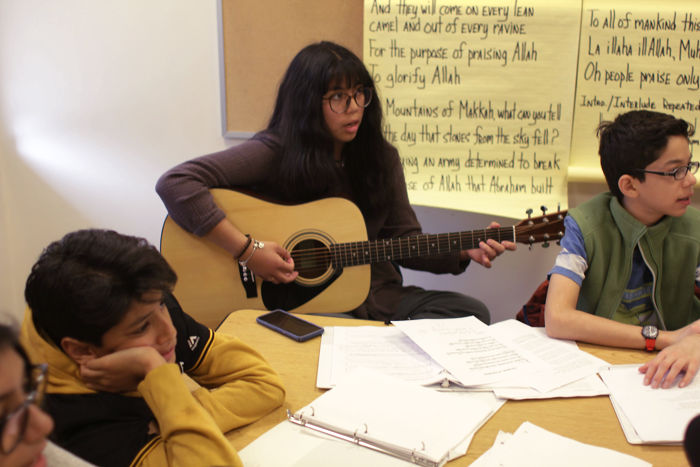

One of the first programs was geared toward youth and stressed the importance of an intimate personal connection with the divine. The curriculum emphasized music, together with values in Islam that are shared with other faith traditions. Once it was developed, however, Georgas needed a place to teach it.

A Jewish educator with whom she had worked, Tehilah Eisenstadt, suggested East End Temple -- hence her 2016 visit.

Once she got agreement from the synagogue’s leaders, Muslim students began learning in the building, a five-story brownstone across from Stuyvesant Square Park. The program grew to include more than 60 children.

“Inevitably,” Georgas said, “we got curious about each other’s communities.”

Sometimes the teachers would leave Islamic teachings on the whiteboards, for example, and the Jewish children would ask about what the Muslim kids were learning, she said.

Photo courtesy of Cordoba House

There also was a feeding program at the synagogue on Sundays, so those folks and the people from Cordoba House would cross paths. Conversations naturally followed, said Rebecca Shore, a member and co-president of East End Temple.

Many of the students, it turned out, already knew one another from school. Shore found this out by accident -- in compiling invitations for her daughter’s bat mitzvah, she recognized Georgas’ son’s name. The two children were in the same seventh grade homeroom.

Georgas was as surprised as Shore to learn of the connection. Our children knew each other “as New Yorkers and school students, not as Jew and Muslim,” Georgas said.

The growing familiarity between the two organizations deepened in July 2017, Shore said, when Stanton became East End Temple’s rabbi. He had a background in activism and interfaith work.

“When Josh came, he already had a relationship with that community and wanted to bring the two communities closer together,” she said. “The feeling was mutual.”

‘Little moments of friendship’

The two communities began to draw closer in a number of ways.

“There were always little moments of friendship,” Georgas said.

A women’s group would get together and share food and talk about spirituality. Georgas invited people to attend jummah prayers on Fridays; Stanton provided space at East End Temple. The synagogue’s cantor, Shira Ginsburg, invited members of Cordoba House to Shabbat rituals.

What other religious communities could be partners with your organization?

In February 2018, Stanton and TCI Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf launched an Islam and Judaism 101 class for the members of Cordoba House and East End Temple. Other events followed, including a joint celebration of Hanukkah and the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad.

The burgeoning friendships would reach a new level in the wake of two tragedies.

The first occurred Oct. 27, 2018, when a gunman walked into the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and opened fire.

“Not only did Cordoba House show up at Shabbat services, they came and spent time with us quietly on Sunday during their school,” Stanton said.

It was an act that Rabbi Stanton said made clear that this relationship was not performative but deep and caring.

“They sat shiva with us,” he said, referring to the Jewish mourning ritual. “They asked caring and compassionate questions, shared a meal. … They just showed up and affirmed that the relationship was real.”

For Stanton, it was a model of how to be present for someone. He couldn’t see then just how soon he would have to apply those lessons.

Not five months later, another gunman entered a house of worship and opened fire, this time at a mosque -- and then a second mosque -- in Christchurch, New Zealand. The horrific attack left people feeling vulnerable, Georgas said.

That Sunday, however, as she and the Cordoba House youth approached East End Temple for religious school, they were greeted by Stanton and the synagogue’s youth with a large card carrying an important message: We are here for you. And we will not let what happened at Christchurch happen to you here.

The East End group sat with their Muslim friends and mourned. And in so acting, Stanton had a revelation.

While listening to the imam talk about the event, he came to appreciate that the needs of those in Cordoba House “were entirely different” from his community’s after the Pittsburgh shooting.

“Muslims murdered while praying are martyrs who go straight to heaven. The imam’s concern was for the Muslims after the event, who were in shock,” Stanton said. This was different from the Jewish focus on mourning the dead.

Has tragedy shaped your organization’s partnerships? What did you learn about your organization and your partners in those times?

Stanton said he realized it was important to “stay in my lane” at this tense time.

“My role was conveying to Muslim parents that their children would be safe at East End Temple -- that we were going to take extraordinary means to ensure that what happened in New Zealand would not happen here,” he said.

And in that moment, he came to appreciate how to “listen and support appropriately” his interfaith community members.

Joining in song

In the wake of these tragedies, Ginsburg became interested in ways to bring the teens closer together.

“Our teens were never in the building at the same time,” she said, so she arranged to get the two groups together to talk. A facilitator was brought in, and over a couple of meetings, a range of ideas and opinions emerged that were recorded on a whiteboard.

Ginsburg and East End Temple composer-in-residence Michael Hunter Ochs took those words and created a song that was performed at a Shabbat service in which Cordoba House members participated.

Called “The Banyan Tree,” the song celebrated the deeper roots that the youths felt bound them together:

I am me because of you.

You are you because of me.

Let’s put our hands together

and shape our destiny.

Like the branches are connected,

someday we will be.

There is room for everyone

underneath the banyan tree.

Taking action on immigration

As the members of East End Temple and Cordoba House were growing closer, the Trump administration’s Muslim ban and focus on restricting immigration sparked fear and sadness among the Muslim community -- feelings that were shared by members of the temple.

“Every Jewish person I have ever met has an immigration story,” Stanton said.

immigrants being held by ICE.

Photo courtesy of East End Temple

The newfound friendship with Cordoba House further sensitized East End’s members to the plight of Muslims in America.

“We shared an underlying sense of fear and sadness, and that fear was very palpable,” Ginsburg said. The relationship with Cordoba House forced them to “take stock of who we are, who our neighbors are, and not focus so much on the outcome.”

This commitment led them to the New Sanctuary Coalition, an organization whose board is co-chaired by the Rev. Kaji Douša, the senior pastor of Park Avenue Christian Church and a close friend of Stanton’s. The NSC is a multifaith organization that supports people navigating the immigration system.

How much to get involved, however, was a point of much discussion at East End Temple.

Some wanted to become a sanctuary site for immigrants. That option was nixed, however, following a debate about balancing social justice with the need to work within the law.

“We did not see how we could viably use our space to house immigrants being pursued by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials without overstepping norms and boundaries that we felt were appropriate,” Stanton said.

Instead, the community settled on working with an NSC program that supports immigrants facing detention hearings.

outside the federal building.

Photo courtesy of East End Temple

The vast majority of people in immigration court have no legal counsel. This is daunting enough. But to make the case that they should be allowed to stay in the country, they have to show that they are a part of the New York City community.

Through its training, NSC teaches people to show up at hearings and sit silently in support of individuals in court. The program also supports people who, because of their immigration status, are fearful to go alone to other appointments as well.

East End Temple has hosted these training sessions and been critical in raising volunteers; about 50 families have been involved in the work. When NSC first started the program, there were only about 20 volunteers. Today, that number is about 5,000.

What questions of justice or moral consequence in your community might require an interfaith witness to address?

Shore, who also has done the NSC training, described the impact of 15 to 20 people showing up to support a friend: “You are instructed very clearly to be quiet at the hearings. … It is [our] role to show strength and support in numbers. A case is called up, and everyone will stand to show support.” Very often, she said, “judges will comment directly on that support.”

Moreover, in addition to the cultural connection between the communities, this work was informed by Jewish teachings.

“Anyone who has read the Hebrew Bible knows that … one of the most commonly reiterated [charges] is to care for the one who is made to feel like a stranger among us,” Stanton said.

The Jewish concept of social justice is called tikkun olam in Hebrew -- “healing the world.”

This idea is what Georgas would call a universal value, though in Islam that concept is slightly different.

In Islam, she said, the idea is to “be a steward of the human soul that has been shaped by God’s own breath.”

“We are,” she said, “to be beautiful.”

Moving forward into an uncertain future

What has happened at East End Temple is interfaith lived at a level much deeper than formal dialogues and academic discussions, participants say. It’s Jews and Muslims inviting each other into their lives and, in the case of the temple, their sacred space.

If you shared the story of this interfaith partnership with your board or leadership team, what lessons would they draw from it for your organization’s work?

“Welcoming our neighbors in our sacred home is as holy as it gets,” Stanton said.

Where this relationship goes remains to be seen. The pandemic forced an end to the space-sharing agreement that launched the relationship, though both communities have continued activities online.

For Georgas, shared programming is surely part of the equation in the future, but online programming has reduced costs.

“We will have to see what the requirements and demands are of our community members before making a commitment to being in a particular space permanently,” she said.

Whatever is decided, she knows this: the East End community is there for her and her community.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- What experience have you had developing interfaith relationships? When has that been life-giving to you and your organization? When has that been more difficult?

- What other religious communities could be partners with your organization?

- What questions of justice or moral consequence in your community might require an interfaith witness to address?

- Has tragedy shaped your organization’s partnerships? What did you learn about your organization and your partners in those times?

- If you shared the story of this interfaith partnership with your board or leadership team, what lessons would they draw from it for your organization’s work?