By Andrea Williams

When Dr. André Churchwell, BS’75, was a biomedical engineering student at Vanderbilt, his daily commute from East Nashville was emblematic of the obstacles he faced growing up in a segregated neighborhood and in a city that just a few years earlier had been at the center of the civil rights struggle.

“I would run two blocks from my house down to the bus stop and catch the bus at 7:30,” says André, now the university’s vice chancellor for equity, diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, during a recent tour of his former neighborhood. Pointing out the location, he recalls, “Those old stone bus stop benches there? They didn’t have a shed, so I was pelted with rain, snowed on, everything.”

Yet even when he made it to campus on time, more formidable obstacles awaited him. As one of the few Black students enrolled at the university during the early 1970s, he felt an acute sense of isolation, similar he says to what the unnamed protagonist experiences in Ralph Ellison’s iconic novel Invisible Man.

"I would walk across that campus, and no one would say a thing,” he says. “No, ‘Hello, how are you doing?’ Nothing. I didn’t know anybody, and they didn’t know me."

A few people who crossed paths with André during his undergraduate years cared enough to actually see him. Some of his professors, who knew he was staying off campus to prevent an additional financial burden on his family, arranged a place where he could study while at school. And fellow engineering student Luis Batista, BE’75, whose parents had fled Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba to come to the U.S., became a good friend and remains so to this day. But those types of relationships were a rarity.

“There was no place to get nurtured there,” André says. “If you failed, you failed on your own.”

Nurturing, however, was never in short supply in his family. The Churchwell home provided a much-needed refuge during those anxious, lonely days. “I’d come back to Mom’s hot water cornbread and her turnip greens from the market on Jefferson Street,” he says of his mother, Mary Churchwell. “The world was made right every time I came home.”

I would walk across that campus, and no one would say a thing. No, ‘Hello, how are you doing?’ Nothing. I didn’t know anybody, and they didn’t know me.

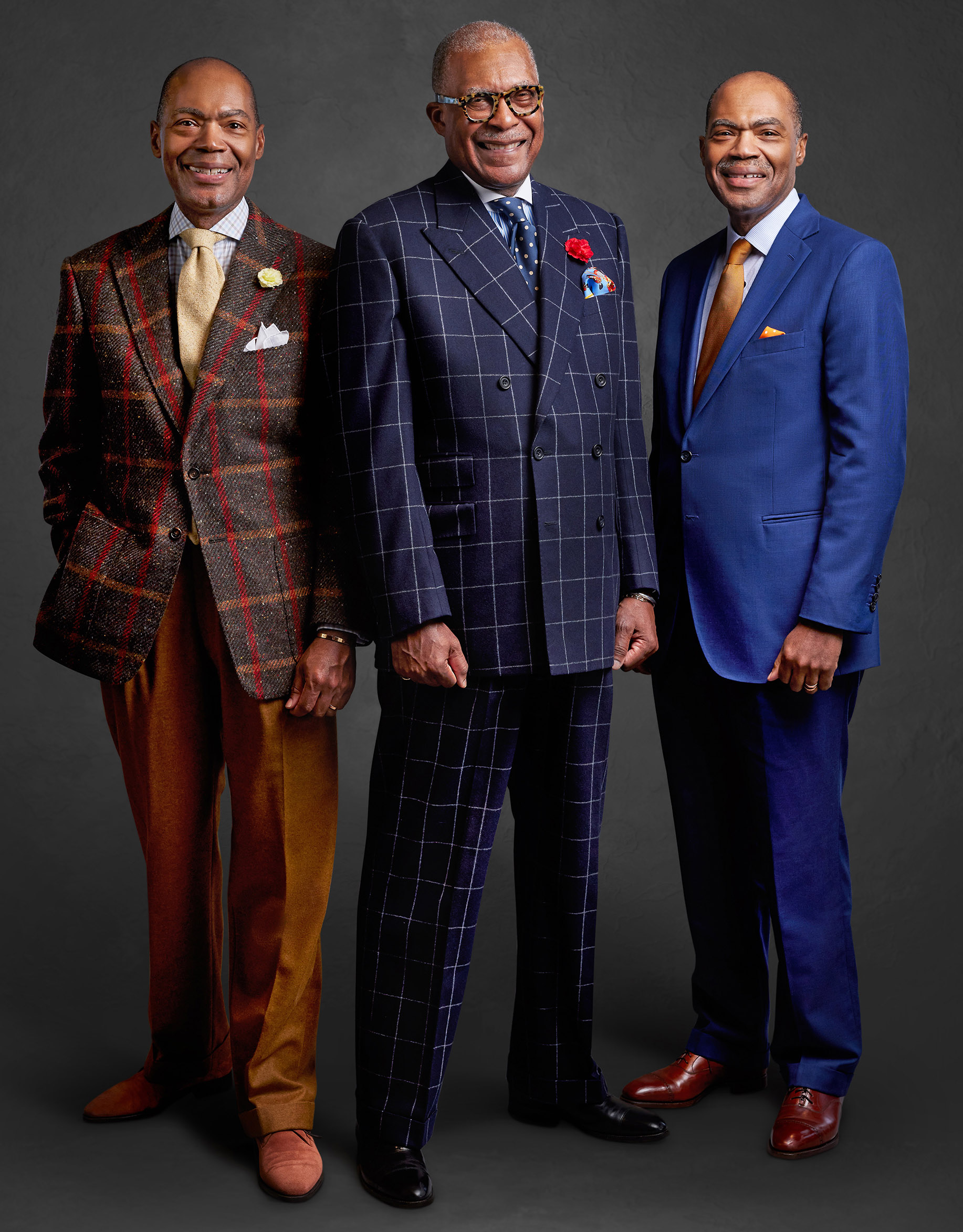

But it was family patriarch Robert who played the most significant role in keeping André—as well as younger twin brothers, Dr. Kevin Churchwell, MD’87, and Dr. Keith Churchwell, who both followed in André’s footsteps to medical school—fixed on the path to success.

Today the three brothers, who were together for 15 years at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, are among the most accomplished physicians and administrators in the country. Kevin, an alumnus of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and former CEO of Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, is now president and CEO of Boston Children’s Hospital. Keith, who was formerly on faculty at the School of Medicine and held a variety of leadership roles at VUMC, is now president of Yale New Haven Hospital. Both credit their older brother for helping blaze a trail for them.

“Keith and I went to college the same year that André finished med school,” Kevin says. “I go to MIT, Keith goes to Harvard. And you see the impact of André’s generation on some of the major colleges in the nation. I called it ‘standing in the breach’ in terms of what they did for the next generation, and Keith and I benefited from it.”

André, who earned his M.D. from Harvard Medical School, views what he and his brothers have accomplished as helping dispel a pernicious myth about Black youths.

“One of the great challenges for young Black kids—now, then, whenever—is that, when you have failure out in the white man’s world, and you don’t quite have the confidence and resilience built in, you can go to the bottom,” he says. “You can believe the public myth that Black folks aren’t smart, that Black folks can’t be successful compared to white folks.

"Dad wouldn’t let you believe that. He wouldn’t let you fail."

And it is for this reason that André works so tirelessly in his capacity as vice chancellor to bridge for Vanderbilt students the kind of gap he dealt with as an undergraduate between his own campus experience and the invaluable nurturing he received from his own family. For today’s students who feel “othered,” unvalued or invisible, he wants Vanderbilt to be as much of a place of refuge and support as his home was for him. And just like his father, he’s not going to let them fail.

“André is the ideal person to lead the university’s diversity and inclusion efforts,” Chancellor Daniel Diermeier says. “He has firsthand experience with discrimination, having grown up in Nashville and attended Vanderbilt at a time when opportunities were rarely extended to African Americans. Yet throughout his distinguished career, he has always looked to bridge the divide and bring people together in spite of their differences. He understands as well as anyone what can be accomplished when members of a community look out for one another and create a culture of belonging where everybody can thrive.”

TRAILBLAZER AND ROLE MODEL

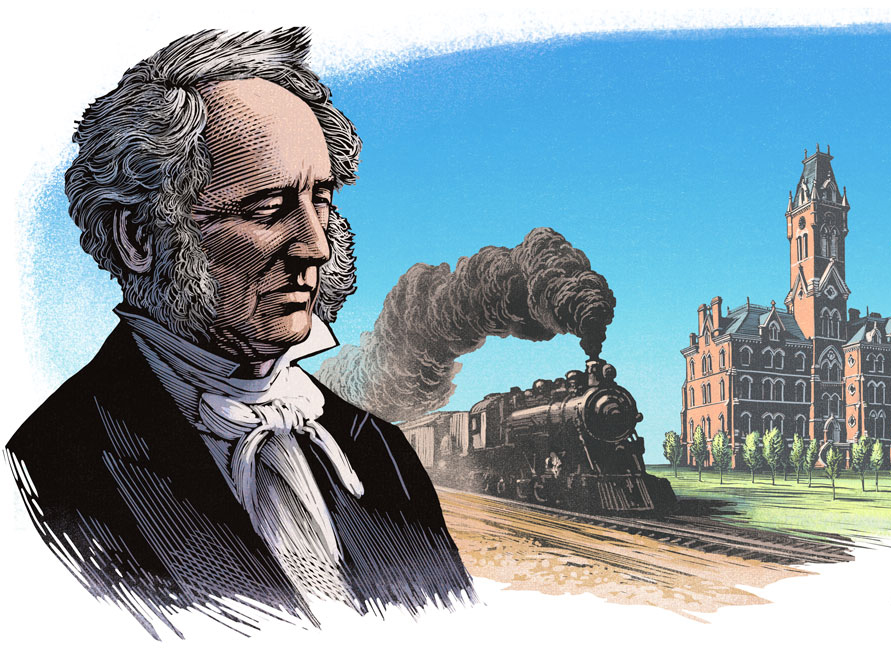

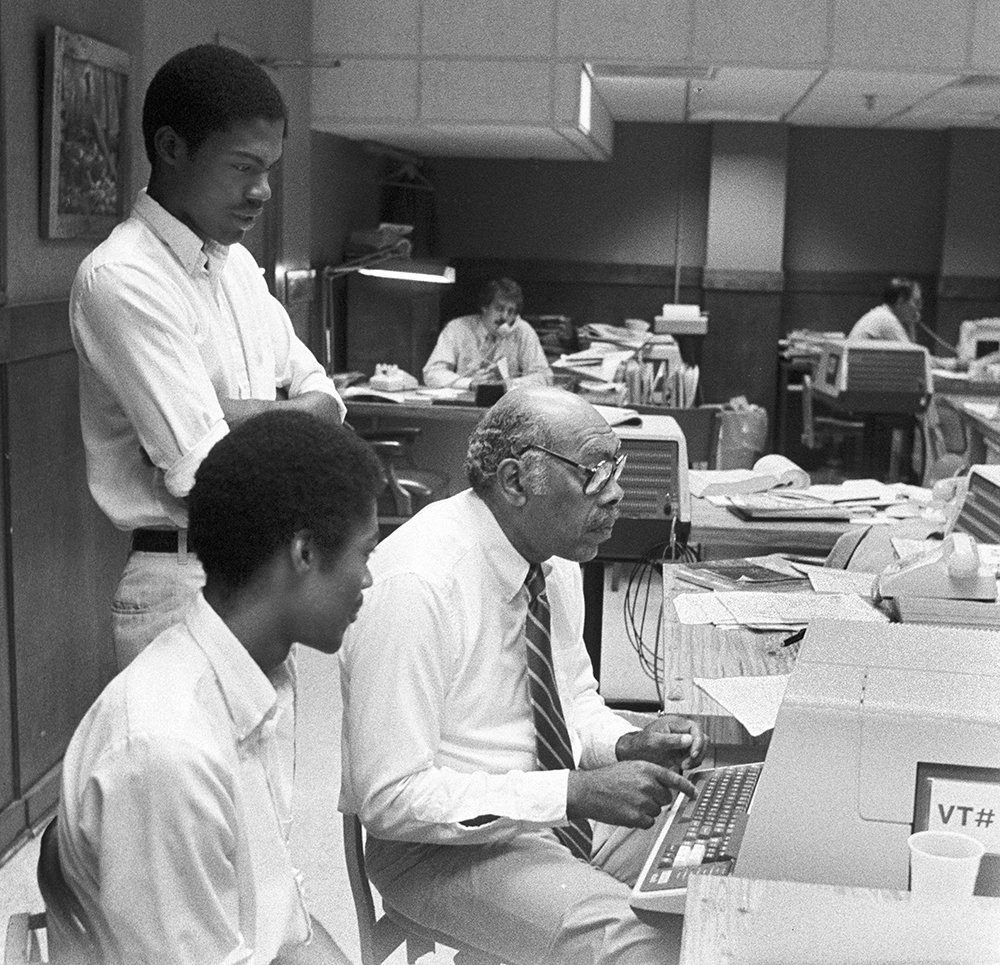

In many ways Robert Churchwell was himself a trailblazer. He challenged the racist status quo in his own career when he became the first Black reporter at the Nashville Banner newspaper in 1950. From a distance, it was a mark of pioneering progress, a promise of even better things to come. Up close, though, the weight of this advancement was heavy, even debilitating.

Robert wasn’t even given a desk for his first five years or so at the paper, and André remembers his father working at home, rising early each morning so he could submit his stories to the paper’s city editor, and then returning home. There was added friction, too, as those stories rarely reflected the community Robert had hoped to represent in his new position. As the city became awash in its own civil rights struggle—with Black students staging sit-ins, taking freedom rides, and integrating public schools—Robert was unable to report on any of it.

“He purposely, as most heroes do, kept all that hidden from us,” André says. “For the better part of our lives, as a matter of fact.”

Still, he heard things, as most kids do. He now remembers pushback from other Black people in the community who saw his father’s failure to publish articles about the issues that affected them most as a capitulation to the white establishment instead of the overt silencing it actually was.

“He did all he could to have stories on Black people in the newspaper that were positive, but the publishers fought him tooth and nail,” he explains. “The 1960 bombing of the home of Z. Alexander Looby, the civil rights lawyer—he wrote the story, but I don’t think it was ever published. So he, as a great writer, faced challenges just trying to do his job.”

Much of what André heard was from conversations between his parents, between husband and wife working to raise a family and learning to navigate a world that was changing—but perhaps not rapidly enough. It would be many years before he and his siblings understood the tension and anxiety that simmered beneath the surface of those conversations—before the true stakes of being a Black reporter in the South and facing racism of the most blatant kind, along with the post-traumatic stress disorder his father suffered after World War II, culminated in an ongoing bout with depression.

“I don’t think my siblings and I actually found out about that until maybe 10 years before he passed away,” André says. “He and Mom hid that, his antidepressant medicines, his thoughts of quitting the newspaper, and all that.”

But Robert never stopped working—both as a reporter for the Banner who needed to provide for his family and as a man tasked with both staring down and superseding the limits of racism. “When you’re first in something—even now, but certainly a few decades ago—if you didn’t succeed, you might not ever see another Black person in that role again,” André says. “Jackie Robinson thought about that. Dad thought about that. And that was another reason he kept going.”

‘LIFE OF THE MIND’

It was to André’s benefit that his father kept going and that he sought to impart his hard-earned wisdom along the way. To be clear, those lessons were never formally taught to the Churchwell children. Their father was too savvy for that, too committed to the absorption of his teachings to let his ego dictate their delivery.

André remembers that his father’s favorite day of the year was graduation at Fisk University. He covered the festivities as a Banner reporter; as a proud alumnus, he brought his children along to meet poet and novelist Arna Bontemps and painter Aaron Douglas, men who were friends, mentors and Fisk faculty members.

Robert was a voracious reader, drinking in the works of renowned Black writers including Ellison, Bontemps, and Langston Hughes, as much as Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and the canon’s other white scribes. He wanted his children to develop an appreciation for books, telling them regularly that, no matter their chosen vocation, they needed to master the humanities. But he also knew that simply shoving a book in front of a teenager wasn’t the best approach. Instead he presented André with an offer he couldn’t refuse: During a sweltering Nashville summer, he could earn money by cutting grass—or by reading through a stack of books in his father’s air-conditioned library. The decision was a no-brainer.

“I think he realized that if we knew about the arts and music, and important people and moments in history, it would afford us a leg up on the next student,” André says. “We would do better in school, and it would afford us an opportunity to ‘live a life of the mind,’ which he kept talking about.”

More than anything, though, Robert Churchwell taught his five children—André, along with Robert, Marisa, and twins Kevin and Keith—through his example. Once, on the way home from picking up Keith and Kevin from elementary school, Robert stopped to give a hitchhiker, a perfect stranger, a ride.

“I always think about that because he was trying to teach us how to interact with and be a part of the public fabric,” Keith says. “And remind us of our responsibilities as individuals for people whom we may not know but who are actually part of the overall brother- and sisterhood.”

There are countless Churchwell family traits, passed from one relative to another, from their sense of humor to their pattern of speech, but one that is most unmistakable is an ability to excel in nearly any circumstance. Like an affinity for reading and appreciation for Frank Sinatra, this, too, was impressed by the elder Churchwell in the most subtle of ways. There was one wall in Robert’s library—the only wall that wasn’t covered in cases filled with books—known as the family wall of fame. It featured enough examples of Black excellence that André and his siblings felt inspired to greatness all on their own.

“You would see his degree from Fisk; if you had an award in high school, that would go up there; when he would get an award for journalism, it would go there,” André says. “And he would say, ‘You know, there’s a bunch of empty spots on the wall up here, guys.’ So we would work our rear ends off to see what we could do to get on that wall.”

Despite the urging from their father, Kevin says that there was never a sense of competition or pressure within the family. “It wasn’t pressure, but the expectation was that you would do well,” he explains. “Learning was fun. It was something that we very much enjoyed. But underneath that was: You need to make sure you’re doing as well as you possibly can.”

“The accomplishments of the Churchwell family are nothing short of extraordinary,” says Dr. Jeff Balser, MD’90, PhD’90, president and CEO of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and dean of Vanderbilt School of Medicine. “Kevin and Keith made significant contributions in leadership roles at the Medical Center and continue to excel in their current roles at Boston Children’s and Yale. And I’m deeply indebted to André for his transformative leadership in the School of Medicine and Medical Center, championing our efforts to increase diversity and inclusion. His efforts will have a lasting impact.”

'COME BACK, GIVE BACK'

The East Nashville of André’s youth is nothing like the gentrified, hipster haven of today. Back then, it was an enclave for Black families like his—rich in spirit, drive and integrity, even if they were lacking in financial resources. There were white families in East Nashville, too, but they lived on the other side of McFerrin Avenue, the unofficial dividing line that separated white from non-white, have from have-not.

“On the north side of McFerrin was Black East Nashville,” André explains. “On the south side of McFerrin, across the street, was white East Nashville. And you could tell the difference. Our street that ended at McFerrin was a gravel road that the city just recently had put some asphalt on. There were no lines, no sidewalks. But if you crossed over McFerrin, there was a sidewalk 20-feet wide. The streetlights went all the way down the street on the south side, but there was just one streetlight per block on the Black side.”

Nashville didn’t begin integrating André’s high school, East High School, until 1970—16 years after the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. The process wasn’t smooth, and he says his years at East were marked by occasional race riots, some hostility, and staunch self-segregation. To keep the peace, administrators held separate competitions for Miss East High, crowning a Black and white winner.

But in the classroom, there was no such distinction. All students were forced to learn and compete together—and oftentimes faculty and staff were stunned to find that the Black students could hold their own.

“If you look at the yearbook, at the National Honor Society, over half those kids were Black,” André says. “Dad was always saying, ‘You’re as good as anyone; you’re as smart as anyone; and look how you performed there. All you did was just reflect that.’”

Graduating third out of 301 students gave André the courage to break from family HBCU tradition and apply to predominantly white institutions. He was accepted to both Vanderbilt and Notre Dame, but financial constraints kept him in Nashville—a blessing in disguise, he would soon realize.

After Harvard for medical school and then Emory University School of Medicine for his internship, residency and fellowship, he embarked on a career as a cardiologist on the faculty at Emory. But the possibility of returning to Nashville—and helping further the progress in diversity efforts he saw unfolding at Vanderbilt—was never far from his mind. He eventually would join the leadership at VUMC, where he served as its chief diversity officer from 2015 until 2021.

Today he is continuing those diversity efforts on the university side, working closely with staff members in the Office for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion to create a culture that ensures all students, faculty and staff feel welcomed, supported and part of the broader Vanderbilt community.

Kevin notes that André is uniquely suited to guide Vanderbilt toward a more equitable and inclusive future. “He’s been very intentional about his own development, from the positions he’s taken on to his learning development,” he says. “He’s a scholar of the work of diversity, and in doing that, he presents not just what is happening in front of him, but the plan three years from now, five years from now, 10 years from now. Vanderbilt is lucky to have him.”

There’s also the added benefit of André’s lived experiences—including those as an “invisible” Vanderbilt undergrad. “If you had asked me, after I finished Vanderbilt, if I would be coming back and doing this, I’m not sure I would’ve said that,” he says. “But as time went on, and my recognition of the education I received here and how it has transported me grew, I had to say, ‘Thank God for Vanderbilt.’

“And that’s why I’m back. Dad’s message was ‘Come back, give back.’”