Extreme Risk Laws Save Lives

Last Updated: 12.20.2024

Learn More:

Summary

When a person is in crisis and considering harming themselves or others, they often exhibit clear warning signs. Family members and law enforcement are usually the first people to see these signs. But, in too many cases, they have few tools to take preventative action despite picking up on the signs.

Extreme Risk laws empower loved ones or law enforcement to intervene and temporarily prevent someone in crisis from accessing firearms. These laws, sometimes referred to as “red flag” laws, can help de-escalate emergency situations. They are a proven way to intervene before an incident of gun violence—such as a firearm suicide or mass shooting—occurs and takes more lives. States around the country are increasingly turning to Extreme Risk laws as a common-sense way to help reduce gun violence.

Introduction

Many shooters exhibit warning signs that they pose a serious threat before a shooting.

We hear about the many warning signs indicating that shooters posed a serious threat before a shooting with numbing regularity. Extreme Risk laws give key community members a way to intervene before these warning signs escalate into tragedies without going through the criminal court system.

These laws permit immediate family members and law enforcement to petition a civil court for an order—often called an extreme risk protection order (ERPO)—to temporarily remove guns from dangerous situations.1The names for these orders can vary by state. They are sometimes also known as gun violence restraining orders (GVROs), gun violence protective orders (GVPOs), high-risk protection orders, or lethal violence protective orders. If the court finds that someone poses a serious risk of injuring themselves or others with a firearm, that person is temporarily prohibited from purchasing and possessing guns. The guns they already own will also be held by law enforcement or another authorized party while the order is in effect.

Otherwise, under current federal law, a person is only prohibited from having guns if they fall into one of several categories, including those convicted of certain crimes, adjudicated as mentally ill or involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital, or who are subject to a final domestic violence restraining order.218 U.S.C. § 922(d), (g). A person who displays warning signs of suicide or other acts of violence, but who is not prohibited under current law, would still be legally able to buy and possess guns. Extreme Risk laws help to fill this gap, protecting public safety and allowing people in crisis the chance to seek the help they need.

Following the mass shooting at a school in Parkland, Florida, in February 2018, lawmakers across the country have sought to close this gap.

Since then, 16 states and Washington, DC, have passed Extreme Risk laws, bringing the total number of states with these laws to 21. As of 2024, just over half the United States population lives in a state with an Extreme Risk law. Despite their relative newness, people in these states are utilizing these life-saving laws, a thorough Everytown analysis of Extreme Risk petitions found.3Everytown chose to focus on the number of petitions filed at both the state- and county-level rather than the number of orders granted by a judge to better understand where and how often individuals are seeking orders.

- Between 1999 and 2023, at least 48,513 Extreme Risk petitions were filed. The majority of these petitions (46,729 or 96 percent) have been filed since the Parkland shooting.4Analysis includes all available data as of December 2024 from the 19 states with Extreme Risk laws in effect and Washington, DC. Data was collected from state agencies through public records requests. When public records were not available, data was obtained from advocacy organizations, researchers, and/or media sources. No data from Indiana was available at the time of collection. Where possible, the analysis includes only temporary and emergency petitions and excludes final orders.

- The use of these life-saving laws did not stop during the COVID-19 pandemic, with at least 11,534 petitions filed across the country in 2020 and 2021.

- Within many states, these laws are being used comprehensively—of the states with county-level data available, at least one petition has been filed in over half of all counties. And in states like Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island, a petition has been filed in every county in the state.

Which states have Extreme Risk laws?

21 states have adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Alabama has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Alaska has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Arizona has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Arkansas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

California has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, immediate family members, employers, coworkers, teachers, roommates, people with a child in common or who have a dating relationship

Extreme Risk Law

Colorado has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, certain medical professionals, and certain educators

Extreme Risk Law

Connecticut has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, and medical professionals

Extreme Risk Law

Delaware has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Florida has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

Georgia has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Hawaii has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, medical professionals, educators, and colleagues

Extreme Risk Law

Idaho has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Illinois has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Indiana has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

Iowa has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Kansas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Kentucky has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Louisiana has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Maine has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Maryland has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family members, doctors, and mental health professionals

Extreme Risk Law

Massachusetts has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Family/household members, gun licensing authorities, certain law enforcement; certain health care providers; school principal/administrator

Extreme Risk Law

Michigan has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, certain health care providers

Extreme Risk Law

Minnesota has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Mississippi has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Missouri has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Montana has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Nebraska has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Nevada has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

New Hampshire has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

New Jersey has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

New Mexico has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

New York has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, district attorneys, family/household members, school administrators, certain medical professionals

Extreme Risk Law

North Carolina has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

North Dakota has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Ohio has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Oklahoma has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Oregon has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

Pennsylvania has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Rhode Island has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

South Carolina has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

South Dakota has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Tennessee has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Texas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Utah has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Vermont has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- States attorneys and the Office of the Attorney General; family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

Virginia has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and Commonwealth Attorneys

Extreme Risk Law

Washington has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

West Virginia has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Wisconsin has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Wyoming has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Petitions Filed by State and Year

| State (Month/Year law took effect) | 1999–2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Rate of Petitions Filed per 100,000 people (2023) | Total Petitions Filed (All Years) | Counties Reporting at Least One Petition Filed (%), 2018–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California (1/2016)5Data represents the total number of orders issued. | 189 | 424 | 1,110 | 1,284 | 1,384 | 1,909 | 2,125 | 5.4 | 8,425 | 90% |

| Colorado (4/2019)6Colorado’s law went into effect on April 12, 2019. However, the courts did not begin accepting petitions until January 2020. | 119 | 148 | 122 | 182 | 3.2 | 571 | 70% | |||

| Connecticut (10/1999) | 1,564 | 268 | 250 | 200 | 224 | 839 | 2,131 | 59.1 | 5,476 | 100% |

| Delaware (1/2019)7Data is not available for the first year because Delaware’s law went into effect on December 27, 2018. Data shown for 2019 reflects the period from January to October 2019. Data shown for 2020 reflects the period from July to December 2020. | 21 | 16 | 29 | 13 | 17 | 1.7 | 96 | 100% | ||

| District of Columbia (1/2019)8Data represents the total number of unique cases. Petition counts under 20 have been suppressed, per the policy of the DC Courts. | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 36 | 5.3 | 73 | Not applicable | ||

| Florida (3/2018)9Data represents the total number of temporary petitions filed. | 1,192 | 2,075 | 2,309 | 2,482 | 2907 | 3,522 | 16.5 | 14,487 | 94% | |

| Hawaii (1/2020) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.3 | 6 | 40% | |||

| Illinois (1/2019)10Data reflects the total number of firearm restraining orders issued. | 74 | 67 | 38 | 112 | 244 | 1.9 | 535 | 47% | ||

| Indiana (7/2005)11Data prior to 2023 represent the number of orders issued and are not a comprehensive count of petitions. Data for 2023 are a count of petitions which results in a significantly higher total. | Requested | Requested | Requested | 59 | 176 | 186 | 652 | 9.7 | 1,073 | 84% |

| Maryland (10/2018)12Data shown for 2018 reflects the period from October to December 2018 because Maryland’s law went into effect in October 2018. | 303 | 873 | 712 | 754 | 741 | 697 | 11.3 | 4,080 | 100% | |

| Massachusetts (8/2018) | 10 | 19 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 11 | 0.2 | 68 | Unavailable | |

| Nevada (1/2020)13Data for 2020 reflects the number of high-risk order cases in Carson City from January to October 19, 2020, and in Washoe County from January to November 5, 2020. Data for 2021 reflects the number of new filings statewide. | 8 | 8 | 7 | 22 | 0.7 | 45 | 41% | |||

| New Jersey (1/2019) | 167 | 337 | 349 | 563 | 678 | 7.3 | 2,094 | 100% | ||

| New Mexico (5/2020) | 4 | 3 | 13 | 47 | 2.2 | 67 | 55% | |||

| New York (8/2019) | 167 | 280 | 342 | 2,560 | 5,074 | 25.2 | 8,423 | 100% | ||

| Oregon (1/2018) | 74 | 116 | 144 | 149 | 166 | 186 | 4.4 | 835 | 83% | |

| Rhode Island (6/2018) | 10 | 31 | 35 | 33 | 50 | 53 | 4.9 | 212 | 100% | |

| Vermont (4/2018) | 38 | 38 | 31 | 30 | 22 | 36 | 5.6 | 195 | 93% | |

| Virginia (7/2020)14Data represents the total number of unique cases. | 44 | 131 | 189 | 248 | 2.9 | 612 | 47% | |||

| Washington (12/2016)15Data is not available for the first year because the law went into effect in December of 2016. Data is limited to Superior Court filings and does not include orders reported in lower courts at this time. | 31 | 147 | 161 | 213 | 187 | 122 | 279 | 3.7 | 1,140 | 87% |

| Total | 1,784 | 2,466 | 5,105 | 5,879 | 6,484 | 10,550 | 16,245 | 48,513 |

Key Findings

Evidence shows that temporarily removing guns from people in crisis can reduce the risk of firearm suicide.

Firearm suicide is a significant public health crisis in the United States.16For more information on firearm suicide, see: everytownresearch.org/disrupting-access. Every year, nearly 26,000 Americans die by firearm suicide, 17Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Provisional Mortality Statistics, Multiple Cause of Death (accessed September 1, 2024). Average: 2019 to 2023. including nearly 1,300 children and teens.18 Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Provisional Mortality Statistics, Multiple Cause of Death (accessed September 1, 2024). Average: 2019 to 2023. Ages: 0–19. Nearly six out of every 10 gun deaths in the US are suicides, an average of 71 deaths a day. 19Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Provisional Mortality Statistics, Multiple Cause of Death (accessed September 1, 2024). Average: 2019 to 2023.

Among commonly used methods of self-harm, firearms are by far the most lethal, with a fatality rate of approximately 90 percent, whereas, 4 percent of people who attempt suicide using other methods die.20Andrew Conner, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 2 (2019): 885–95, https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-1324. The vast majority of survivors of a suicide attempt do not go on to die by suicide.21David Owens, Judith Horrocks, and Allan House, “Fatal and Non-Fatal Repetition of Self-Harm: Systematic Review,” British Journal of Psychiatry 181, no. 3 (2002): 193–99, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. Research shows that access to a firearm triples one’s risk of death by suicide. This elevated risk of harm applies not only to the gun owner but also to everyone in the household.22Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (2014): 101–10, https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301.

Red flag laws reduce firearm suicides.

14%

Connecticut saw a 14% reduction in the firearm suicide rate.

7.5%

Indiana saw a 7.5% reduction in the firearm suicide rate.

After Connecticut increased its enforcement of its Extreme Risk law,23Conn. Gen. Stat. § 29-38c one study found the law to be associated with a 14 percent reduction in the state’s firearm suicide rate.24Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-Based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on Suicide Rates, 1981–2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (August 2018): 855–62, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700250. In the 10 years since Indiana passed its Extreme Risk law in 2005,25Ind. Code § 35-47-14-1, et seq. the state’s firearm suicide rate decreased by 7.5 percent.26Kivisto and Phalen, “Effects of Firearm Seizure Laws.”

While it is always hard to measure events that “didn’t happen,” a number of studies have estimated the number of lives saved by these laws. A multistate study found that one suicide was averted for every 17 ERPOs issued, which translates to 269 lives saved.27Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Suicide Prevention Effects of Extreme Risk Protection Order Laws in Four States,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online 52, no. 3 (August 2024), https://jaapl.org/content/early/2024/08/27/JAAPL.240056-24. This study also found that when looking at only those cases in which the individual had demonstrated a threat of self-harm, for every 13 ERPOs issued, a suicide was prevented.28Swanson et al., “Suicide Prevention Effects of Extreme Risk Protection Order Laws in Four States.” Two studies in Connecticut found that one suicide was prevented for approximately every 11-22 gun removals carried out under the law.29Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Implementation and Effectiveness of Connecticut’s Risk-Based Gun Removal Law: Does It Prevent Suicides?” Law and Contemporary Problems 80 (2017): 179–208; Matthew Miller et al., “Updated Estimate of the Number of Extreme Risk Protection Orders Needed to Prevent 1 Suicide,” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 6 (June 2024): e2414864, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14864. Similarly, another study estimated that Indiana’s Extreme Risk law averted one suicide for approximately every 10 gun removals.30Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Criminal Justice and Suicide Outcomes with Indiana’s Risk-Based Gun Seizure Law,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online 47, no. 2 (2019): 188–97, http://hdl.handle.net/1805/22638.

Perpetrators of mass shootings and school shootings often display warning signs before committing violent acts.

An Everytown original analysis of mass shootings from 2015 to 2022 revealed that in nearly a third of incidents the shooter exhibited warning signs that they posed a risk to themselves or others before the shooting.31Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. “Mass Shootings in America,” March 2023, https://everytownresearch.org/mass-shooting-report. These warning signs are even more apparent among perpetrators of school violence.32Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. “Keeping Our Schools Safe: A Plan for Preventing Mass Shootings and Ending All Gun Violence in American Schools,” February 2020, https://bit.ly/2TFIfM9.

The United States Secret Service and the United States Department of Education have studied school violence incidents over the past few decades, and have consistently found that most perpetrators, prior to a shooting, exhibited behavioral warning signs that caused others to be concerned. The most recent study on incidents from 2008 through 2017 found that 100 percent of perpetrators showed concerning behaviors, and in 77 percent of incidents, at least one person—most often a peer—knew about their plan.33National Threat Assessment Center, “Protecting America’s Schools: A US Secret Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence” (US Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security, 2019), https://bit.ly/2U7vnwa.

For example, students and teachers at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, reported that the mass shooter displayed threatening behavior before the February 2018 shooting. His mother had contacted law enforcement on multiple occasions regarding his behavior and he was known to possess firearms.34Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, Initial Report Submitted To The Governor, Speaker Of The House Of Representatives And Senate President, January 2, 2019, fdle.state.fl.us/MSDHS/CommissionReport.pdf. Yet no action could be taken to remove his firearms. In response to that tragedy where 17 students and staff were shot and killed and 17 more were wounded, Florida passed its own Extreme Risk law.35Fla. Stat. § 790.401.

Likewise, the shooter in the May 2014 shooting in Isla Vista, California, displayed numerous warning signs, including homicidal and suicidal threats. Though his parents alerted law enforcement, the shooter did not meet the criteria for emergency mental health commitment.36Kate Pickert, “Mental-Health Lessons Emerge from Isla Vista Slayings,” Time, May 27, 2014, https://goo.gl/UL5jLX. As a result, he kept his guns, which he used in the killing spree three weeks later. In response to that tragic shooting, California passed its own Extreme Risk law.37Cal. Penal Code § 18125; Cal. Penal Code § 18150; Cal. Penal Code § 18175.

Interventions in states with Extreme Risk laws have already prevented these potential tragedies.

A study in California details 21 cases in which a Gun Violence Restraining Order (GVRO)— California’s name for an Extreme Risk order—was used in efforts to prevent mass shootings. In one case involving an employee who threatened to shoot his supervisor and other employees at a car dealership if he was fired, a manager informed the police and a GVRO was obtained the following day. Five firearms were recovered through the order.38Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Extreme Risk Protection Orders Intended to Prevent Mass Shootings,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 9 (2019): 655–58, https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-2162.

In Maryland, an Extreme Risk law passed in 2018 has been invoked in at least four cases involving “significant threats” against schools, according to the leaders of the Maryland Sheriffs’ Association.39Broadwater L. Sheriff, “Maryland’s ‘Red Flag’ Law Prompted Gun Seizures after Four ‘Significant Threats’ against Schools,” The Baltimore Sun, January 15, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190116044427/https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/politics/bs-md-red-flag-update-20190115-story.html.

In Florida, which passed an Extreme Risk law in 2018, the law has been invoked in multiple cases of potential school violence, including in one case involving a student who was accused of stalking an ex-girlfriend and threatening to kill himself.40Kennedy E. Tate student’s AR-15, father’s 54 guns removed under new red flag law. Pensacola News Journal. July 9, 2018. https://bit.ly/2UHmaba. The law was also invoked in another case in which a potential school shooter said killing people would be “addicting.”41Lipscomb J, “Florida’s Post-Parkland ‘Red Flag’ Law Has Taken Guns from Dozens of Dangerous People,” Miami New Times, August 7, 2018, bit.ly/2ORW56U.

In Seattle, a coalition of city and county officials launched a regional firearms enforcement unit that supports, tracks, and enforces all firearm surrender orders issued within the county.42The coalition included the Seattle City Attorney’s Office, Seattle Police Department, King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, and King County Sheriff’s Office. In the unit’s first year, it recovered 200 firearms as a result of 48 ERPOs. According to the City Attorney’s Office, the use of ERPOs has been effective in temporarily preventing access to firearms by students who threatened violence against themselves, the school, and other students.43Twelve-month period from January 2018 to December 2018. Acquired via correspondence with Christopher Anderson, director of the Domestic Violence Unit of the Seattle City Attorney’s Office.

Thoughtful drafting and implementation, along with widespread awareness of Extreme Risk laws, are critical to ensuring their effectiveness.

Even though Extreme Risk laws have been proven effective in reducing rates of gun suicide and have prevented countless acts of gun violence across the country, these laws are most effective when they are thoughtfully drafted and implemented, and when there is widespread awareness of their existence. Recent events have shown just how critical this is.

As stay-at-home orders were issued across the country at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March and April 2020, court operations were significantly impacted, but the demand for ERPOs did not stop. State governors, attorneys general, and courts had to adapt their policies and procedures to ensure continued access to the Extreme Risk order process. Many states designated Extreme Risk filings as essential court proceedings and provided virtual access to proceedings. California, DC, Florida, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington all saw increased demand for ERPOs during 2020 compared to 2019.

On April 15, 2021, a gunman shot at least 13 people, killing eight, before dying by gun suicide at a FedEx warehouse in Indianapolis, Indiana.44William Mansell et al., “8 Killed in Mass Shooting at Indianapolis FedEx Facility; Suspect, 19, Was Former Employee,” ABC News, April 18, 2021, https://abcn.ws/2Spt8FS. Prior to the incident, the shooter’s family raised concerns that he was a risk to himself and law enforcement used Indiana’s Extreme Risk law to remove a firearm from the home. Unfortunately, law enforcement and prosecutors decided not to pursue a full order, which would have prohibited him from purchasing or possessing guns. A few months later, the shooter legally purchased the new guns that he used in the shooting.45Casey Smith, “Prosecutor: FedEx Shooter Didn’t Have ‘Red Flag’ Hearing,” Associated Press, April 19, 2021, https://bit.ly/3be6cjy. While some were quick to point to the shooting as proof that Extreme Risk laws don’t work, it actually highlights the need for proper implementation of Extreme Risk laws. Had the full order been pursued in light of the evidence that the shooter posed a threat, it is likely the shooter would have not been able to legally access the guns used in this tragedy.

The tragedy in Indianapolis highlights the importance of ensuring awareness of the law so that it is used effectively. While at least one petition has been filed in more than half of all counties in states with these laws, usage of Extreme Risk laws is still low in many counties. Evidence suggests this may be due to a lack of awareness. In a 2019 study of the implementation of Indiana’s law, two judges expressed that the law’s effectiveness was limited by a lack of awareness of the law among the legal parties responsible for its implementation.46Swanson et al., “Criminal Justice and Suicide Outcomes.” A 2020 study of Washington’s law speculated that there was a lack of awareness of the law among the general public.47Ali Rowhani-Rahbar et al., “Extreme Risk Protection Orders in Washington: A Statewide Descriptive Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 173, no. 5 (2020): 342–49, https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0594. These findings underscore the need for educational efforts geared toward law enforcement, court personnel, and eligible petitioners outside of the legal system.

To increase awareness and ensure effective implementation of the law, state government agencies and nonprofit organizations have launched training programs and public awareness campaigns. Following the passage of New York’s Extreme Risk law in 2019, the governor’s office held conferences to educate eligible petitioners about when and how to file for an ERPO. The state also launched a website and call center to help eligible petitioners identify warning signs and navigate the filing process.48New York State Governor’s Office, “Governor Cuomo Launches Statewide Education Campaign on New Red Flag Law,” press release, September 18, 2019, https://on.ny.gov/3eAL7ld. When New Jersey’s Extreme Risk law took effect in 2019, the state attorney general issued guidelines to prosecutors and law enforcement on how to implement the law and held trainings for community members.49Leah Mishkin, “AG’s Office Gets the Word Out on State’s New Red Flag Law,” NJ Spotlight News, September 16, 2019, https://bit.ly/3uBxwzD.

In 2019, Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund launched a public awareness campaign called “One Thing You Can Do” to educate communities on how to use the Extreme Risk law in their state.50https://onethingtodo.org/ Since 2019, Moms Demand Action volunteers have conducted more than 700 events and trainings on how Extreme Risk laws work in communities across the country. These events, sometimes held in partnership with community stakeholders, such as law enforcement and public health entities, are designed to raise awareness about how and why an Extreme Risk order could be used to prevent someone from harming themselves or others.51Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, “Extreme Risk / Red Flag Laws,” https://momsdemandaction.org/work/red-flag-laws/.

The federal government can support these efforts by establishing a federal grant program for states to train law enforcement and court personnel on Extreme Risk laws, develop protocols for enforcement of orders, and raise public awareness of this life-saving process. Legislation that would establish such a program was introduced in the 116th Congress in February 2019,52116th Congress (2019–2020), H.R. 1236, Extreme Risk Protection Order Act of 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1236. and in April 2021, President Biden urged Congress to pass similar legislation.53Biden-Harris White House, “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Initial Actions to Address the Gun Violence Public Health Epidemic,” April 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/32VYp5b; Alex Gangitano and Brett Samuels, “Biden to Announce Executive Action on Ghost Guns, Red Flag Laws,” The Hill, April 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3boZ3wL.

Extreme Risk laws have robust due process protections.

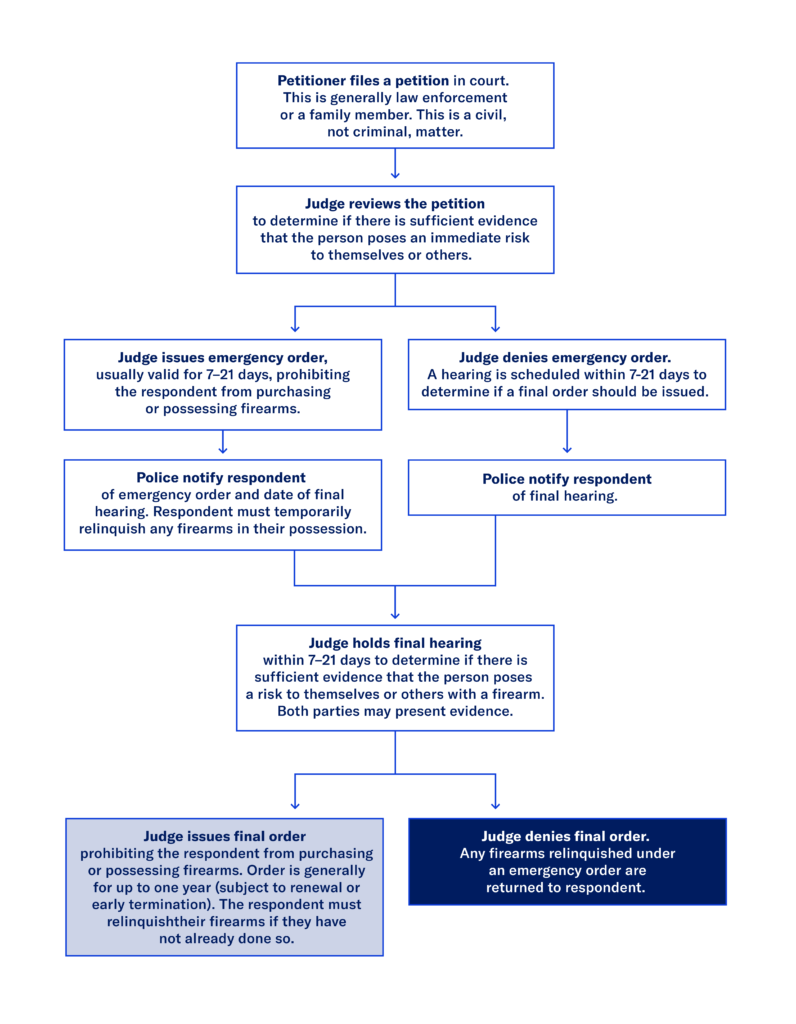

Extreme Risk laws are designed to defuse dangerous situations while also ensuring due process and a system of checks and balances.54“[p]rocedural due process rules are meant to protect persons not from the deprivation, but from the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.” Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247, 259 (1978). In each state with an Extreme Risk law, only specific groups of people may request an ERPO. For example, states typically limit ERPO petitioners to law enforcement officers and family or household members. These limitations mean that only people who are very close to the person at risk of harming themselves or others, or who are trained to identify and respond to such risks, can bring forth these cases.

In a crisis situation where a petitioner presents clear evidence that someone (i.e., a respondent) poses an immediate risk, a judge can issue an emergency ERPO. This emergency ERPO immediately suspends firearms access until a full hearing can be held, usually within seven to 21 days. A longer-term final ERPO can be issued only following a hearing, prior to which the respondent is given notice, and during which they have an opportunity to be heard and respond to evidence.

When an ERPO case is filed in court, the burden to prove the need for an ERPO is placed on the petitioner. The petitioner must present evidence to a judge demonstrating that the respondent poses a significant danger of harming themselves or others with a firearm. State laws typically specify the types of evidence that a judge can consider in an ERPO case. For example, evidence of recent acts and threats of violence or recent unlawful or reckless use of a firearm. The respondent then has the opportunity to respond to any evidence presented, and present their own evidence. Many states’ laws include penalties that apply if the petitioner presents false evidence.

After considering all of the evidence, the judge can dismiss the case or order a final ERPO. The final ERPO typically lasts one year. However, in most states, respondents have the ability to petition to terminate the ERPO prior to its expiration date. If there is evidence that an ERPO should be extended beyond its initial end date, another hearing is required during which the respondent is afforded the same rights as the initial hearing.

The model process for obtaining an extreme risk protection order provides due process protections.

The United States Supreme Court has recognized, in multiple contexts, that this process—a pre-hearing deprivation followed by a full hearing within a reasonable time frame—satisfies the due process of law required by our Constitution. Following the framework established by the Supreme Court, multiple federal and state courts have issued rulings that strongly suggest they would uphold an Extreme Risk law if challenged in court on due process grounds.55Everytown for Gun Safety, “Extreme Risk Protection Orders Respect Due Process,” March 2020, https://bit.ly/3vo62y7; Everytown for Gun Safety, “Colorado Moms Demand Action Applauds County Court Ruling Upholding the State’s Red Flag Law,” May 2020, https://bit.ly/3hPvSHg.

- Law enforcement agencies may also complete internal review processes before filing an application. In Florida, for example, the Broward County Sheriff’s Office has instituted a review process for all ERPO petitions so that when a Broward County sheriff’s deputy identifies a case as requiring an ERPO, it must be approved by their superiors and then reviewed by attorneys before the case can be filed in court.

- Initial evidence suggests that judges are taking the process and procedures of the law seriously and are reviewing the cases carefully. Of the 190 petitions filed in 2018 and 2019 in Oregon, 38 were denied for reasons such as unqualified petitioners, petitioners failing to appear at the hearing, and failure to establish clear and convincing evidence. And under Oregon’s law, if a judge grants a one-year order after reviewing the filed petition, the respondent may request a hearing to determine if the order should stay in place. The hearing must then occur within 21 days. In 2019, a hearing was requested by 32 respondents and an order was dismissed in only 12 of these cases.

- A case in Washington illustrates the due process provided under these laws. Law enforcement filed a petition for an ERPO after a man who recently fired a gun in a public place called 911, threatened to “start shooting,” then attempted to draw a gun when police arrived. Before filing the petition, the officers interviewed the man’s family members and witnesses of the incidents. The court granted an emergency ERPO. Fourteen days later and after receiving notice, the man attended a court hearing where he was represented by an attorney. At the hearing, the man agreed to extend the ERPO for two months pending further evaluation of his case.

In a recent survey of 2,500 likely voters, 85 percent of respondents favored Congress passing an Extreme Risk law, as well as 78 percent of gun owners.56Global Strategy Group. Voters call for background checks, strong Red Flag bill, conducted on behalf of Everytown for Gun Safety. September 6, 2019. https://every.tw/2lM0L48.

Conclusion

Multiple studies prove that Extreme Risk laws work to prevent firearm suicide. Growing evidence also shows they can help prevent would-be mass shooters from committing violence. An overwhelming majority of Americans on both sides of the aisle support Extreme Risk laws. Legislatures should proactively act to protect public safety by enacting Extreme Risk laws. States that already have them can improve them by expanding the groups of eligible petitioners, clarifying and strengthening existing laws, and enacting training programs and public awareness campaigns. And Congress can support these efforts by establishing a grant program. Elected officials should not wait for the next tragedy to occur before taking action.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, a national network of local crisis centers that provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24/7. Call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org/chat to chat online with a counselor.

Appendix A: Extreme Risk Stories

The anecdotes in Appendix A illustrate the importance of Extreme Risk legislation in removing firearms from dangerous situations.

Appendix B: Extreme Risk Laws by State

Appendix B lists the various permutations of Extreme Risk laws and procedures by state.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.