Pat Dodson: The Morrison government must step up

The royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody was established by the Hawke government in August 1987 because manifold deaths had fomented common suspicions that foul play was endemic in police stations and prisons across the land. As the commission would report in April 1991, the reality was less eventful: Aboriginal people were dying in custody so frequently – but at rates no higher than the non-Aboriginal population – simply because they were being jailed in such disproportionate numbers.

Thirty years on from the royal commission, similar suspicions are gathering again because, proportionately, even more Aboriginal people are in custody today and are dying there. The commonwealth government seems almost nonchalant about this festering crisis: “All lives matter,” we were told during Senate estimates last week by senator Amanda Stoker.

According to her, responsibility for dealing with Aboriginal deaths in custody is overwhelmingly a matter for the states and territories. The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), which sits in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and is responsible for developing and implementing commonwealth policies, was just as offhand last week when it said that the new national agreement on Closing the Gap offered a way to deal with the crisis. One of the targets in the agreement aims, by 2031, to reduce the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults held in incarceration by at least 15%. That is a pathetic aspiration.

The federal government must stop handballing the crisis of Aboriginal deaths in custody among NIAA and the Departments of Home Affairs and the attorney general, and passing off responsibility to states and territories. How can we expect police and prison guards to be held accountable when this government prefers to eschew responsibility? The Morrison government must step up and be accountable.

Pat Dodson is a Labor senator for Western Australia

Lidia Thorpe: It’s a matter of life and death

There are families in continual mourning across this country. The pain and hurt is a deep wound. When will we have peace?

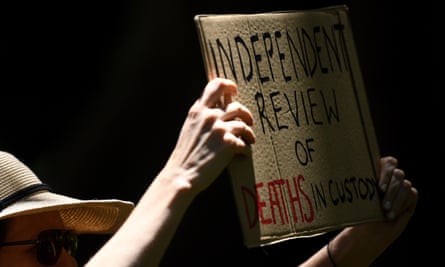

Four more Aboriginal people have died in custody this month. Well over 450 Aboriginal people have died since the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody handed down its findings.

We remind our so-called “leaders” that there’s so much left to do. It’s a matter of life and death. The royal commission’s recommendations must be implemented in full.

I say to this government: come to speak to our communities and our elders. Talk with the families who have lost loved ones. We want the prime minister to take up the invitation from families of those who have had a loved one die in custody to meet with them, ahead of the 15 April anniversary of the royal commission.

We need greater transparency around the reporting of deaths in custody, and a ban on lethal chokeholds.

Our people have the answers and the solutions to ending our over-imprisonment. There are solutions to ending the incarceration of Aboriginal people and deaths in custody. They’ve had the solutions for 30 years and they still haven’t put them into practice.

We mourn, and we remember. And we keep calling for action.

Lidia Thorpe is a Greens senator for Victoria and a Gunnai Gunditjmara and Djab Wurrung woman

Latoya Aroha Rule: Decolonisation is at the heart of the movement

It’s important to locate Black critique on the elements of the carceral system that require reform; those laid out in the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody’s recommendations, those established through findings in knee-high death reports of Aboriginal people since, and those focusing on issues like the need to ban spit hoods and other archaic killing devices that my own family are currently advocating towards.

Without these procedural and legislative changes there is not much hope for those currently incarcerated or those at risk of being locked up. This stands too for those working on the outside on prevention – those working to keep Aboriginal children safe and out of state punishment centres and the like.

However, it is just as critical, if not more so, to acknowledge that decolonisation must stand at the heart of the movement against Aboriginal deaths in custody; the abolition of policing and prisons, systemic violence and brutality is one step toward supporting and sustaining the lives of Aboriginal people.

Land has always been at the centre of global struggles against colonialism. It is clear that without conceptualising the movement against Aboriginal deaths in custody as one of Aboriginal sovereignty and governance, in many ways, state actors retain their function. True and ultimate decarceration and abolition rests with people like police and prison officers, their unions and the millionaire legal teams who make their fortunes off our deaths becoming obsolete.

Latoya Aroha Rule is an Aboriginal and Māori, Takatāpui person residing in Sydney on stolen Gadigal land. They’re a PhD candidate at the University of Technology Sydney, an educator and a freelance writer

Hannah McGlade: Prisons are simply not rehabilitative

Australian society was founded on violence towards Aboriginal people, with incarceration a key feature of this history. The truth is there was genocide in this country and racism against Aboriginal people is leading to discrimination at every stage of the criminal justice process. And our voices are constantly silenced.

Western Australia incarcerates more Aboriginal youth than anywhere and also has more deaths in custody. We see a direct link to the violence that Aboriginal children, youth and families experience from the state: widespread removal from families, racial profiling and stereotyping and even incarceration at just 10 years of age.

We urgently need a rethink of carceral approaches fuelling the horrific rate of Aboriginal incarceration in this country. Prisons are simply not rehabilitative. Aboriginal women experience strip-searching in violation of their human rights, even though they have backgrounds of trauma and violence, and men are especially subjected to inhumane and solitary confinement that increase the risk of suicide and disability.

The Australian Law Reform Commission’s Pathways to Justice Inquiry, tabled in 2018, has been ignored by governments. It said states should re-establish the Aboriginal Justice Advisory Committee, develop Aboriginal justice agreements and support justice reinvestment – investing in communities to prevent offending. Indigenous incarceration costs Australia $9bn annually and the punitive approach is failing.

It is clear our people are treated with callous indifference including by the “justice” system. This is not human rights or reconciliation, but evidence of a settler state that refuses to respect Indigenous peoples and our human rights commitments, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Dr Hannah McGlade is a member of the UN permanent forum for Indigenous issues

Thalia Anthony: Bias runs deep in the penal system

There is a commonality in the lives and deaths investigated by the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody and the almost 500 First Nations lives taken since. They all tell a story of an Australian penal system predicated on systemic racism. They are causalities of a society that has targeted First Nations lives since colonisation.

We only need to look to recent months to see how the penal system sacrifices the lives of First Nations people. This year, four First Nations lives were taken in custody in almost one fortnight. There are more than 20 pending coronial inquests for First Nations deaths in custody across Western Australia, Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia.

Bias runs deep in the penal system. It infiltrates the hyper-policing of First Nations people, the disproportionate rates of arrests, bail refusals and imprisonment and the conditions in custody, which can be characterised as wanton neglect and violence.

To spend the final conscious moments in custody and away from loved ones, without a voice, is something First Nations people have endured too often. Yet governments continue to shift the blame and claim, based on a flawed methodology that most of the recommendations of the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody have been implemented. Grieving families along with Aboriginal legal services have to endure the struggle of campaigning for basic reforms that would save lives, such as the decriminalisation of public intoxication and banning spit hoods. But the victories are few and far between. A systemic response that empowers First Nations people in the change process is needed to combat systemic racism in the penal system.