Councilmember Delishia Porterfield had not heard of Fusus when a request to extend the company’s contract came across her desk in January. Porterfield is chair of the Budget and Finance Committee, and so official council requests from Metro’s various departments get filed under her name.

“MNPD bought this technology without coming to council — I do not believe they were trying to be nefarious, but I had concerns with it,” Porterfield tells the Scene, recounting a flurry of events that had transpired over the previous two weeks. “I did not have any real knowledge or information on it, but I heard from a couple people in the community who also had concerns.”

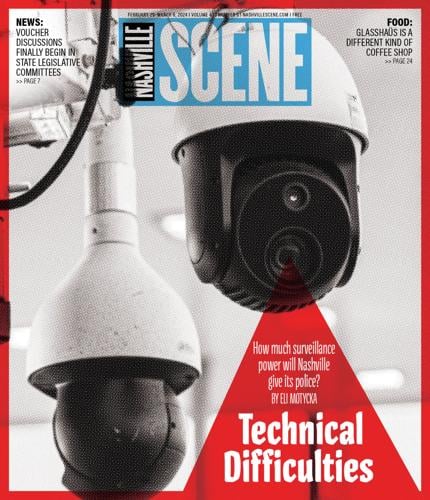

The Metro Nashville Police Department first signed a contract with the Atlanta-based company in 2022. Fusus was part of a growing department affinity for advanced technology capable of collecting and synthesizing vast amounts of data quickly. These tools allow law enforcement to see and hear across a city, advancing an illusion of instantly processing stolen license plates and rogue gunshots into quick and effective officer responses. Police killings of Black people across the country and waves of ensuing protests in 2020 left the department understaffed and newly committed to the idea of “precision policing,” the institutional response to public concern about officers’ indiscriminate use of police power. Vendors, hoping to land contracts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, pushed cutting-edge technology vowing to save lives and strengthen community trust.

In the past year, MNPD has expanded its surveillance network with automated license plate readers and Fusus, a combination of hardware and software that enables police to access registered camera feeds remotely. An $800,000 line item for ShotSpotter, an expansive audio-collection gadget eyed for Metro Development and Housing Agency properties, has lingered on MNPD’s budget request since 2021.

All three of these technologies — Fusus-integrated video, license plate readers and ShotSpotter — are unsettled issues within Metro. Their continued use in Nashville is contingent on budget allocations, council votes, contract approvals, regulatory ordinances and executive action (or inaction). Many are poorly understood by voters and their elected officials. Businesses, neighborhoods and some Metro councilmembers have clamored for more technology, which they see as essential to deterring, identifying and prosecuting illegal activity across Nashville. Reports by Nashville’s Community Review Board (formerly the Community Oversight Board) describe them as underregulated and ineffective tools expected to fuel the overpolicing of low-income communities and communities of color. Social justice groups warn of a “surveillance state” indiscriminately accumulating vulnerable data with little transparency or accountability. No technology has produced much working data or been subject to rigorous, unbiased study. Growing markets for consumer drones and facial-recognition technology ensure new vendors may soon come bearing new pitches that prompt old questions about police power, privacy and public safety.

Leading elected officials like Porterfield and Mayor Freddie O’Connell — an LPR opponent when he was a district councilmember — are proven skeptics of MNPD’s surveillance regime. On Feb. 5, Porterfield posted on social media that MNPD would drop Fusus pending a new contract.

The Fusus episode exposes two things: widespread confusion about something very important, and conflicting views within the Metro government about the limits of police power. In the coming months, new contracts for LPRs and Fusus will force O’Connell, MNPD, councilmembers and the public to chart the city’s course on privacy, police public safety and civil rights.

“As of today, MNPD is no longer using Fusus technology,” Porterfield wrote on Feb 5. “A new contract will be negotiated prior to September and if it includes surveillance it will come back before the council with a public hearing. We will have a presentation to discuss the technology at that time, prior to council approval.”

When he found out about the Fusus contract in January, O’Connell sent technology lieutenant Dave Rosenberg to get a briefing at MNPD’s central command. Formerly a Bellevue councilmember, Rosenberg wrote the city ordinance requiring council approval and a public hearing before Metro installs new surveillance technology — regulations that Fusus slipped in 2022.

“In lieu of a briefing, we wanted to make sure we had some information about the program,” O’Connell tells the Scene. “We believe that MNPD can use the implementation that they are using right now, and that the approach we took to partially disable the technology means the lack of council approval has been cured.”

Fusus combines public and private video feeds into one dashboard, displayed to law enforcement as a digital map. It had been operating in Nashville unbeknownst to elected officials since 2022. The program enabled police to access camera feeds around the city based on agreements with owners aided by products including fususONE, fususCORE, fususREGISTRY, fususVAULT, fususOPS, fususTIPS, fususAlert, and fususANALYTICS. All are aspects of integrating and expanding the various camera feeds directly and indirectly accessible by police, who — until earlier this month — could see registered cameras displayed on a map and notify owners to request a feed. Observant passersby can spot cameras on doorsteps or hanging in clusters on private trailers across Nashville.

Flashing blue lights give the impression of a police presence in the parking lot of an apartment complex or at the McDonald’s near Centennial Park; instead, these trailers are purchased directly from private companies like LiveView Technologies and SkyCop (which advertises its own gunshot recognition system). Fusus can link them all together. Such an expansion of power is raising privacy questions around the country. Amazon, which makes the popular doorbell camera Ring, announced on Jan. 24 that it would end a built-in option to share video with law enforcement. In recent years, police departments in Lexington, Ky., Minneapolis and Providence, R.I., have all adopted Fusus-specific policies and oversight.

LiveView Technologies surveillance trailer in a McDonald’s parking lot

“People have been giving us video for decades to help us build cases,” says Greg Blair, deputy chief of MNPD’s Crime Control Strategies Bureau. “The old way was driving to a location, getting a hold of an individual who can operate the system, obtaining the video — Fusus eliminates those steps. It pulls that all together and sends it to us quicker.”

While its future remains uncertain, the current $175,000 agreement signed by MNPD Chief John Drake and Fusus executive Mark Wood runs through Sept. 26. As of February, MNPD still counts more than 1,100 registered commercial and residential cameras in its Fusus network. Police cannot tap into these video feeds directly. Earlier this month, scrutiny from the council and the mayor prompted a pause on MNPD’s use of Fusus integration.

“Metro legal had some discussions amongst six or seven attorneys and couldn’t agree on the ordinance and definitions, so they told us to deactivate the camera feeds,” Blair tells the Scene. “The camera part has been turned off until council votes, I think sometime in August. Right now, we can’t even see our own cameras through the system.”

Fusus was operating unknown to O’Connell when he took office in September. Nothing had come to the chamber when he was a councilmember. There was no floor debate or rousing public spectacle, as was the case with license plate readers. (O’Connell consistently opposed LPRs and joined 13 colleagues opposing full LPR implementation in one of his last council votes in August.) He hadn’t seen a Fusus budget request or a slide deck. There was no memo or transition briefing from MNPD or Mayor John Cooper’s outgoing administration.

“On Friday afternoon, the mayor called me into his office late,” Metro legal director Wally Dietz told a joint council committee on Feb. 5. “He had three asks: Can we delete the function that permits the police to have real-time access to private cameras? Can we keep the price under $250,000? Can we come up with a systemic fix so that we’re not in this place again?”

Dietz addressed both the council’s Budget and Finance Committee and the Public Health and Safety Committee, 23 total members. (Councilmembers Erin Evans, Jordan Huffman, Jeff Gregg, Joy Kimbrough and Porterfield serve on both.) A new Fusus agreement, along with any future contracts for surveillance-related technology, will likely pass through this same majority before a vote on the council floor.

“As of this morning, the police have — ‘unplugged’ is my word, I’m not a tech person,” Dietz told the group. “They unplugged Fusus. They have disconnected from the software program completely.”

Dietz further clarified his report. O’Connell had requested a “kill switch” to eliminate private video feeds from being remotely accessed by MNPD. Police may continue to use other aspects of Fusus, but will have to collect video the old-fashioned way — visiting business owners and neighborhoods, sometimes with portable storage devices, to review and request files. In the future, police will seek council approval for contracts like this, Dietz assured the body.

Curious councilmembers probed Dietz for basic information. On at least one contract question, Dietz deferred to Deputy Chief Chris Gilder, MNPD’s representative that day, who quickly emerged as the room’s subject matter expert. No one knew exactly what was going on. The mayor learned about Fusus in January, a few days before Porterfield dug into the contract renewal. Porterfield initially told the public that MNPD was “no longer using Fusus technology,” which wasn’t exactly right — Dietz clarified a few hours later that MNPD was disabling private camera feeds, but would soon reactivate other aspects of the system.

When asked about his philosophical views on privacy and technology, O’Connell pauses.

“I’ve always been mindful that systems can wind up having adverse impacts for otherwise law-abiding systems or citizens,” O’Connell tells the Scene. “It’s not my personal preference to walk down the streets in my neighborhood and be on everybody’s Ring cameras, but I know that that’s what my neighbors have decided to help them feel safer in their own homes. We want to let police do police work, and we will make recommendations or raise concerns for them to consider.”

Over the past few years, MNPD has consistently led the public and elected officials in its enthusiasm and understanding of surveillance technologies. Encouraged by salespeople pursuing lucrative business opportunities, top-ranking law enforcement has also been the primary driver of adopting license plate readers and Fusus. ShotSpotter, sitting on the department’s backburner, provides instructive insight into police fidelity to exciting but unproven surveillance technology. Chiefs and deputies swap emails about what they want and how to get it, organizing campaigns like the effort that successfully marshaled LPR legislation through multiple readings, tense debates, accusations of systemic racism, public outcry, council opposition and an expensive pilot program that returned middling results.

The Scene — particularly Metro Council columnist Nicole Williams — has covered that effort extensively over the past three years. Officers attend trade conferences, where they learn about new products and see the gadgetry used by peer agencies around the country.

“Interesting (while we continue to push for LPR’s and Shotspotter)” reads the subject line of a 2021 email from MNPD Chief John Drake to top brass about San Diego police drones. A few emails later, the conversation shifted to LPRs. Assistant Chief Mike Hagar told colleagues, “Gilder or I will be providing a briefing sheet to executive and command staff so that informed calls can be made to council members.”

In an email sent a few months later, Chris Meyer, an executive at tech consultancy Slalom, recapped a meeting with Drake and MNPD’s information and technology director John Singleton about “storytelling and building business cases to push ideas like license plate readers and ShotSpotter to city council.” Meyer was selling MNPD on Virtual Command Post, a police workflow app that centralizes case information.

Such pushes for new police tech have produced mixed results. Police considered and adopted Fusus outside the public view, eventually triggering a backlash from elected officials 16 months into the program. Members of the Community Review Board did not know about the technology until August, nearly a year after it had been adopted. Councilmembers debated LPRs for nearly two years before a split council approved a pilot program in December 2022, then full LPR implementation in August 2023. An online interactive map shows the pilot program’s 24 operational cameras around Davidson County. When the pilot ended on July 22, LPRs went offline. They’ll remain down until the city finalizes an agreement with vendors.

License plate reader debates briefly galvanized broad opposition for police surveillance anchored by prominent city groups like the NAACP, the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition, the American Muslim Advisory Council, Conexión Américas, Open Table Nashville, Stand Up Nashville and SEIU Local 205, constituencies that comprised O’Connell’s political base. In regular floor speeches, Councilmembers Zulfat Suara (a Black Muslim woman) and Sandra Sepulveda (a Latina woman) appealed to their colleagues about how constant surveillance threatens people to whom society regularly denies the presumption of innocence.

“If it doesn’t happen to you, if you’re not part of that group, you really don’t know,” Suara said on the Metro Council floor in February 2022. “As a Black mother, as an immigrant, as someone invited here by the United States government, I am still under a microscope. That is what we are talking about. For one life that is lost or one family that is impacted by this, I would lose a million cars.”

She drew applause from the gallery.

Back in 2018, Nashville allocated money to pilot ShotSpotter in Cayce Homes, Napier and parts of North Nashville, including Buena Vista and Elizabeth Park. These majority-Black neighborhoods make up some of the city’s highest concentrations of poverty and gun violence. Crucially, they also include properties overseen by the Metro Development and Housing Authority. More government-owned real estate means greater control over the neighborhood — ideal for ShotSpotter, which relies on a series of acoustic sensors that need to be placed and secured across a few square miles. Together, these sensors form an audio dragnet that, in theory, immediately notifies police of gunshots without a 911 call.

ShotSpotter, which has since rebranded to SoundThinking Inc., required Nashville to sign for at least two years. The city wanted to sign for one. Over the next two years, as city finances got rocky and the public began to look at local law enforcement more closely, MNPD’s push fell apart. Hoping to address gun violence in North Nashville, Councilmember Brandon Taylor prompted MNPD to reexamine ShotSpotter in early 2021.

“I love this technology,” Chief Drake wrote to Hagar in January of that year. A week later, Deputy Chief Natalie Lokey summarized the department’s ShotSpotter history in an email with the subject line “RE: Spot Spotter.”

“At the time it was being considered, all the key players that would be needed to put this program in place were onboard and ready,” wrote Lokey. (Lokey retired from MNPD in April 2022 and now serves as president of the National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives. She declined the Scene’s interview request.) “The program would cover a 3 square mile area, and the areas that were identified were generally around Cumberland View, Cheatham place, Andrew Jackson Courts, Casey [sic], Napier, and Sudekum.”

“We need to consider how we want to introduce this to the citizens of Davidson County,” she continued. “We will have to convey that this is not an intrusive tool and is a safety measure that is vital to all our citizens.”

Drake, Hagar, Lokey and other top MNPD officials reviewed the use of ShotSpotter in Detroit, Baltimore and Chicago. In June 2021, the city’s Capital Improvements Budget approved (but did not allocate) $800,000 for the system. ShotSpotter costs ticked up to $810,000 in the 2022 CIB but remained a single line in a 376-page document. That same spring, the Nashville CRB (then the COB) released a memo questioning ShotSpotter’s efficacy.

“There is great excitement in the policing community regarding ShotSpotter, but there is also some significant trepidation surrounding the technology,” the report reads. “It is a fair characterization to say that evidence surrounding the technology is mixed at best, and that the majority of evidence in favor of ShotSpotter comes from the company itself.”

In 2023, ShotSpotter funding was approved again over two years — $380,000 in FY24 and $410,000 in FY25 — but tagged as a low-priority request without an official department recommendation. Deputy Chief Blair tells the Scene that MNPD is no longer pursuing ShotSpotter, part of a trend that includes Atlanta and Chicago.

“It’s not moving forward anytime soon,” Blair tells the Scene. “It’s sitting out there in la-la land.”

I ask Councilmember Taylor what happened.

“It doesn’t work,” he tells me in a text. He follows up a few minutes later.

“Inaccurate readings which can lead to inaccurate policing.”

Metro’s CRB, then operating as the Community Oversight Board, furnished reports on LPRs, ShotSpotter and Fusus that dug into Taylor’s same concern: What does it mean for police surveillance technologies to work?

First, there is the immediate question of whether the electronics literally function correctly. License plate readers require certain contrast, light and resolution to accurately pick up numbers, for example — a glitch that hit headlines when new Tennessee tags stumped highway cameras in 2022. They miss some plates and misread others. Wind, ambient sounds, tree canopy and structures can all cause faulty ShotSpotter readings; sensors misidentify loud noises and miss actual gunshots.

Police, councilmembers, businesses and neighbors often push for expanded surveillance under the impression that it reduces crime — the second capacity in which the public understands these technologies to work. Crime rates across the board are far below highs from the 1980s and 1990s according to the most recent statistics provided by MNPD.

“Safety is something that needs to be co-produced,” says John Buntin of policy group the Council on Criminal Justice. “It’s not just the job of the police or the courts. It’s something that healthy neighborhoods naturally produce. We don’t have a great understanding of some of these tools, and they haven’t been rigorously studied. They need to be part of a strategy that’s developed with community and with community input.”

From 2019 to 2023, Buntin served as the director of policing and community safety under Mayor John Cooper. He points to the work of Ron Johnson, now formally under the Metro Health Department, to secure grants for public art, library programs, community center upgrades, lighting repairs and traffic calming at Napier and Sudekum as an example of “co-producing safety.”

Surveillance tools, like other policing strategies, require vast amounts of money and time to have even a marginal effect on illegal activity. Over a 10-day stretch studied by the CRB, license plate readers scanned 3.5 million plates, of which they flagged 1,458 as “hits” — meaning they were possibly plates related to stolen cars or criminal activity. Of these, 119 were confirmed by a human officer as hits. Nine resulted in an apprehension, arrest or vehicle recovery. Over all six months, MNPD verified 1,316 hits, stopped 79 vehicles, recovered 80 stolen vehicles, and made 63 arrests. A picture emerges with needle-in-the-haystack levels of tedium: Twenty-four cameras scan and store tens of millions of license plates, which prompt thousands of potential hits, which yield verified hits at less than 10 percent. Each verified hit is another massive gamble for an already understaffed force that results in no arrest or vehicle recovery about 90 percent of the time.

The same is true for ShotSpotter alerts. In 2022, the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project published a third-party analysis of the product, concluding: “ShotSpotter surveillance increases police activity, but it wastes officers’ time. One major study of the technology showed that ShotSpotter fails as an investigative tool, providing no evidence of a gun-related crime more than 90% of the time and producing exceedingly few arrests (less than 1 per 200 stops) and recovered guns (less than 1 per 300 stops).”

As the city decides how to proceed with LPRs, Fusus or ShotSpotter, determining a worthwhile rate of arrests, rules for data retention, training for law enforcement, legal protections for citizens and subsequent questions about privacy and efficacy will fall to O’Connell and the Metro Council. As of August, MNPD had no “Fusus-specific policies, draft policies, or Standardized Operating Procedures” governing its video-collection nerve center. An active memorandum of understanding regarding Fusus between MNPD and Metro Nashville Public Schools prompts further concerns about surveilling people under 18. Cameras during the LPR pilot initially went up without signage required by ordinance, proving that regulation can be ignored even when it has been written into law.

During that same pilot, Bell Road and Trinity Lane had seven cameras between them. Green Hills had none. Across more than 130 cities, ShotSpotter was regularly deployed in Black and Latinx neighborhoods, the same racial demographics that disproportionately face police violence and incarceration. Nashville’s CRB flags all three technologies — ShotSpotter, Fusus and LPRs — as latent threats to equitable policing and citizens’ civil rights.

LPR boosters have dismissed concerns about video being used for immigration enforcement or hypothetical instances of state surveillance. Skeptics have brought up hypothetical situations, like a resentful cop tracking a former romantic partner or state law enforcement commandeering local technology to surveil individuals seeking out-of-state abortion care. In reality, data ownership between governments and private entities — like Fusus or the tech companies that sell LPRs — is new terrain.

“It’s not entirely clear the city can prevent a state or federal subpoena from being executed, if an agency wants to access the data,” Vanderbilt Law School professor Christopher Slobogin told the Scene back in August. Slobogin, a nationally renowned authority on police power and privacy, helped draft Nashville’s LPR legislation. “In the case of immigration, it’s possible immigration authorities could override any attempt by the city to stop access to the data. I think it’s a live issue. If I were the city, I’d be prepared to resist that, probably through litigation.”

Slobogin shares the Vanderbilt campus with Andrew Jackson Professor of History Sarah Igo, a prominent privacy researcher currently working on a book about the Social Security number.

Vandy’s 700 acres in the middle of Midtown are among the most surveilled places in Nashville. Cameras are everywhere. Building entrances are outfitted for swipe cards. Students use university digital infrastructure, from internet access to email accounts. Students involved in divestment activism and graduate student unionization have reported efforts by the administration to track their organizing — the potential consequences of a closely monitored world.

Proponents of mass surveillance commonly respond to concerns with some version of the following: “If I’m not doing anything wrong, I have nothing to fear.”

“That notion breaks down pretty quickly as you think about the freedom you want as a private citizen in a society,” Igo tells the Scene. “On LPRs or other types of capture, you may be fine with that until the moment that you’re not. Information is increasingly mobile, and it doesn’t always stay where you think it should stay.”

After studying centuries of data and privacy, Igo offers a few considerations as Nashville prepares its stance on privacy and public safety.

“Pretty much always, data gathering, maintenance, capture and collection are framed as public goods and offered as some kind of service, convenience, security, safety, protection or knowledge,” she says. “But we don’t have a lot of practice with anticipatory thinking. You think you would never do anything wrong, but you just don’t know what might happen to this data a month or a year down the line.”