When Kara Finnigan communicates with her peers about reforming troubled school districts, she does so with journal articles such as “System-wide Reform in Districts Under Pressure: The Role of Social Networks in Defining, Acquiring, Using, and Diffusing Research Evidence.”

Or with presentations at academic conferences on such topics as “A Tale of Two Districts: The Importance of Collegiality in Urban Education Reform” or “Using Social Network Analysis to Understand Leadership Churn Under Accountability Policies.”

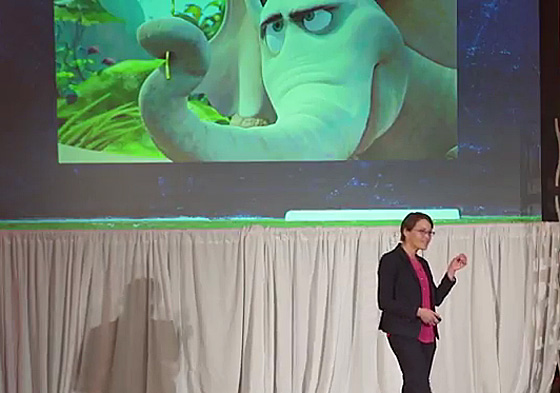

But when the associate professor of educational policy at the Warner School of Education wants to communicate with the policymakers who bring reform about — or with parents and other stakeholders who will be affected — she starts by talking about Horton the elephant.

That’s right: the Dr. Seuss character who placed a speck of dust on a flower and discovered Whoville inside.

Finnigan is not speaking down to her audiences when she talks about Horton; rather, she explains, she’s dangling a “hook” to attract and hold the audience’s attention. She’s acknowledging that scholars need to find different ways to communicate their work to non-academics if scholarly research is to have the broadest possible impact. “Otherwise, nobody’s going to pay attention,” she says.

The importance of this kind of public scholarship was brought home to Finnigan this year when she was one of 32 scholars chosen by the American Educational Research Association to participate in a series of events to better connect research and policy.

This included nearly two days of training in how to give TED-like “ED” talks to:

- Build a stronger bridge between research and policy

- Strengthen understanding of the knowledge base in the field

- Prompt dialogue

“It was a very humbling experience for everybody,” says Finnigan. “These are top scholars who are used to having more time and space to get into the complexities. These are scholars who want you to know the complexities.”

Instead they had to do just the opposite. They had to limit their presentations to five to six minutes. They had to concentrate on key points. Avoid academic jargon. Find a “hook” that non-specialists could relate to.

And they had to think at least as much about their presentation skills as their content. Speaking clearly. Making eye contact. Not cluttering the slides with too much data.

“They forced us to think about the bare bones ideas that we want to make sure people take way. The purpose is to engage people enough so they will then want to go to the papers and other things you’ve done for more information,” Finnigan says.

She’s pleased by the feedback she’s received, not just from these talks, but the blogs (click here for an example) she writes to communicate her findings.

“I didn’t realize how much people had an appetite for this, until I tried these different mechanisms,” she says.

“As academics, we tend to sit in our silos, but the cross-fertilization that occurs when we step out of those silos is what can really bring us to new levels. This is not just about getting my information out for somebody else to take up. I get information back, which pushes me further.”

And yes, the “hooks” do work, she says. People who have heard her ED talk will later meet her, for example, and say, “Oh, I remember. You talked about Horton.” It’s an easy shorthand instead of having to remember a talk’s actual title.

So what does Horton the elephant have to do with school reform?

When Horton looked very closely at that speck of dust, he discovered a community that everybody else overlooked. It provides a nice analogy for Finnigan’s premise that successful reform of troubled K-12 school districts requires a close look at the layers of the system, in order to build stronger relationships, for example, between central office administrators and school-based principals. It also requires focusing on geographic inequities that concentrate students from the poorest neighborhoods in inner city schools.

“Too often we pay too much attention to simple solutions without paying attention to the underlying complexities and layers of an educational system that need to be tended to,” Finnigan says.