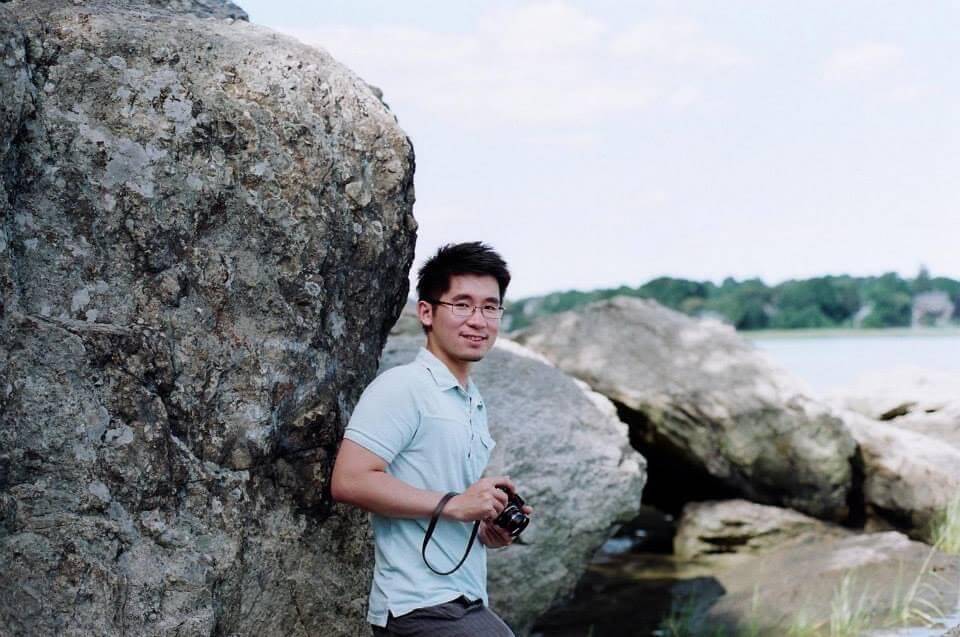

Khiem Tran’s response to drug therapy for advanced colorectal cancer seemed to defy the severity of his disease. After just a few doses of chemotherapy and a targeted drug, the cancer, which had spread from his rectum to his liver, was in full retreat, with a key marker of tumor burden dropping from stratospheric levels to those normally found in people without cancer.

Almost from the start, however, there were hints of a potential problem.

When Tran came to Dana-Farber for chemotherapy infusions or to have a drug pump disconnected, his nurses noted that he appeared to be a bit “off,” not quite himself. They wondered if it might be anxiety — not unusual in someone beginning cancer treatment — or a side effect of medication.

One morning after Tran had undergone a few more cycles of treatment, his family found him in his Watertown home nearly unresponsive, unable to answer questions or speak coherently. At Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), he underwent a series of tests as doctors strove to determine whether he was suffering from an infection, a brain injury, or other disorder. The lab tests, combined with a search of medical literature, led to the discovery that the delirium was caused by a genetic quirk in the way Tran’s body metabolizes chemotherapy — an abnormality reported in only a handful of other patients in medical history.

A treatment that was routing Tran’s cancer was producing alarming abnormalities and delirium. Unless the medical team could find a way to tame the side effects, the therapy would have to be abandoned.

The solution was a treatment protocol designed specifically for Tran, one that curbed his body’s overreaction to chemotherapy and softened the side effects. With it, he was able to continue receiving chemotherapy until his tumors shrank to a point where they could be surgically removed.

The whipsaw of first having a profound response to therapy, then facing the prospect of its cessation, then receiving a novel treatment to make chemotherapy manageable would try the endurance and spirit of any patient. But Tran, who had taken up meditation in college, found in Zen meditation not only an antidote to the uncertainties of his disease but also, he believes, an avenue for marshaling his body’s powers of self-healing. His practice of Zen meditation would increase over the course of his treatment, becoming, in the process, an essential source of strength and clarity.

Ominous signs

Being diagnosed with cancer is always a shock — especially so when the message is delivered by a call to one’s cell phone. Tran was 32, a director of analytics at a local healthcare company, when the call came in late 2019.

The diagnosis was colorectal cancer and the prognosis wasn’t promising.

“When we saw the results of the scan, it was clear it was severe, so we moved fast,” Tran says.

He came with his family to Dana-Farber, where he started care with Douglas Rubinson, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist in the Center for Gastrointestinal Oncology at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center. He also had the support of Dana-Farber’s Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center, which is dedicated to the needs of patients with colorectal cancer who are diagnosed before the age of 50. At the time of diagnosis, Tran’s cancer had spread from his rectum (the lower part of the large intestine) to nearby lymph nodes and formed metastases in his liver.

Once cancer has spread, it often isn’t considered curable, but colon cancer is a rare exception.

“Even when it has metastasized, we have the potential to cure patients,” Rubinson says, “but we need to remove the tumor in the rectum, where it started, as well as the liver — and there needs to be enough healthy liver remaining to perform all its functions.”

So much of Tran’s liver had been overrun by cancer that it wasn’t clear this latter condition would apply.

“Khiem’s burden of disease at diagnosis, with multiple lesions that were each several centimeters in size, meant the likelihood of meeting all those criteria seemed improbable,” Rubinson remarks.

Doctors started Tran on an aggressive chemotherapy regimen called FOLFOXIRI, an acronym of the four drugs within it. It’s generally reserved for the youngest and fittest patients: Only 10% of colon cancers occur in people under age 50, and the vast majority of those are in people in their 40s. To develop it in one’s early 30s is exceedingly rare, although rates for young people have been rising in recent years.

[Learn more about signs and symptoms of colon cancer.]

As is standard at Dana-Farber, Tran’s tumor tissue was analyzed by Oncopanel, a technology platform that identifies genetic abnormalities that can be targeted by specific drugs. Had the scan shown his tumors harbored mutations in KRAS or certain other genes, Tran would have been ineligible for cetuximab, a targeted drug rendered ineffective by such mutations. As it happened, Tran’s tumors were not only free of KRAS mutations, they had another feature that rendered them extraordinarily vulnerable to cetuximab.

“Oncopanel showed that instead of having the normal two copies of the EGFR gene — the specific target of cetuximab — his cancer had 111 copies,” Rubinson says. His cancer seemed to be relying on EGFR to for its growth. “While we usually don’t combine cetuximab with chemotherapy in this situation, we decided to add it to the FOLFOXIRI in the hope that his cancer might be unusually sensitive to it.”

Their hopes were not disappointed. Tran’s response to the combination was, in Rubinson’s words, “really profound.” Scans showed his tumors shrinking dramatically. Tests of a tumor marker protein called CA19-9 — which physicians use to track whether a cancer is advancing or receding — fell from a staggering 8,000 units to a normal level of 26 after just a few treatments.

A sudden turn

Excitement at the exceptional response soon turned to bafflement and concern at the exceptional side effects Tran suffered — the loss of awareness, the confusion. Laboratory tests performed when Tran was in the emergency room showed extremely high rates of ammonia, a sign that his liver was failing, and of lactic acid, usually a sign of pervasive infection.

“An astute hospital resident, Sanjay Kishore, MD, wondered if, instead of being caused by an infection, the problems arose from an idiosyncrasy in Khiem’s metabolism,” Rubinson remarks. “Does his body produce high levels of these chemicals because of a genetic irregularity that alters how his body metabolizes sugar when chemotherapy is used?”

The inpatient genetics team at BWH was called in and began scouring medical literature for similar cases. Joel Krier, MD, MMSc, clinical chief of the hospital’s Division of Genetics, found only a few. Based on a report of a patient in France, he deduced what was likely happening with Tran’s metabolism.

“My care team was extremely helpful. They laid out a clear path for treatment. I wanted to do my part — what I could do every day as a patient.”

Khiem Tran

“We wanted to keep Khiem on this treatment since he was having such a great response,” Rubinson observes. “The last thing we wanted to do was to abandon the therapy, but we couldn’t use it if it was going to be unsafe.”

Rubinson and Krier devised a protocol in which Tran would be admitted to BWH every time he received a chemotherapy treatment and would be given a mixture of nutrients and dietary supplements designed to prevent his body from overproducing the toxic metabolic products that had flooded his system. Over the next few months, he would eventually be admitted to the hospital six times for chemotherapy treatment and the accompanying potion.

To save Tran’s liver, doctors performed a portal vein embolization, cutting off blood flow to the diseased half of the organ and forcing blood into the normal portion, allowing that section to grow. Tran received radiation therapy to his rectal cancer in April 2020. In April, he had surgery to remove the right side of his liver and a small portion of the left side, leaving enough healthy liver to survive. The next month, he had surgery to remove the cancerous tissue in his rectum.

Tran’s liver has now grown back to normal size. Although there have been some complications since his surgery, Tran today is cancer-free.

A mindful ally

For Tran, treatment was a joint undertaking, a blend of medical care and self-care.

“My care team was extremely helpful. They laid out a clear path for treatment,” he relates. “I wanted to do my part — what I could do every day as a patient.”

He began researching ways to enhance the effectiveness of the chemotherapy he was receiving. Drawing on a Dana-Farber study, he began taking vitamin D supplements with his physicians’ approval. On the basis of research emerging from China and Japan, he added turkey tail mushrooms (formally known as Trametes versicolor) to his regimen, again with doctors’ approval.

Bringing his life into alignment with his treatment also had a mental component. He deepened his meditation practice, meditating for hours a day. The practice helped keep him grounded and less prone to runaway fears.

“There’s always anxiety and suspense with this kind of treatment,” he observes. “But your mindfulness of anxiety is not the anxiety itself: you can be aware of it without feeling intense emotion.”

[Get tips on how to start meditation.]

Meditation allowed him to be, if not detached from his fears, more open to them — and less inclined to see cancer as a battle.

“When you read the news, people always talk about the fight against cancer, but that combative attitude can be quite exhausting,” he says. “For me, it was a process of healing, care, kindness, and the motivation to be there for my loved ones and others.”

Tran’s care team marveled at his composure.

“He’s one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever interacted with,” Rubinson says. “He always had a smile, he was never anything but gracious and appreciative of the care he received. I’m sure that behind the scenes he and his family had a lot of tough days, but he didn’t let it impact with how he interacted with his medical team, other than being so thankful for everything Dana-Farber and Brigham and Women’s had provided for him.”

Excellent article.

Excellent patient.

Excellent medical team and excellent

medical care.