Why Your House Was So Expensive

Material-cost inflation, anti-building rules, NIMBY attitudes, and barriers to innovation have created a housing-affordability crisis.

Sign up for Derek’s newsletter here.

There’s no hiding from America’s housing crisis. Do you want to buy a place? Home prices recently surged to all-time highs, after the inventory of available homes plunged to a record low. Want to rent, instead? Rents in June rose at the fastest pace in four decades, in part because new housing construction relative to the total population was lower in the 2010s than in any decade on record.

America’s housing crisis doesn’t just show up in higher prices. It shows up in surging homelessness in states such as California that do a miserable job housing its population. It shows up in climate change, because the inability to build sufficient homes in and near cities pushes more people out to the suburbs, where their carbon footprint is higher. It shows up in declining fertility, because the cost of housing discourages families from having as many kids as they’d like.

Name just about any problem the U.S. has suffered from in the past decade. Inequality? Obesity? A vague, pervasive sense of doom? You could tell a housing story about all of them. In the essay “The Housing Theory of Everything,” the writers Sam Bowman, John Myers, and Ben Southwood argue that the housing shortage in the Western world—“too few homes being built where people want to live”—prices out middle-class workers from high-productivity zones, forces people to spend more time sitting in their cars to commute long distances, and reduces the availability of homes and overall growth rates. There you have housing’s contribution to more inequality, obesity, and gloom. And this generalized Western trend is especially bad in the U.S. Although homeownership is strongly encouraged by federal tax law, America has fewer dwellings per thousand inhabitants than the European Union or Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average.

This year, I wrote that America needs an abundance agenda to increase the supply of the most important things in the economy. In the past six months, I’ve written about how to create medical abundance by tackling the scarcity of physicians. I’ve written about how to create energy abundance by deploying the clean-energy breakthroughs we’ve already achieved. I’ve written about new ways to kick-start scientific experimentation that could, down the line, yield incredible breakthroughs.

But you could argue that none of that matters if we don’t build enough homes for people to live in. So the most important question for American abundance might be: Why is it so hard to build a house in America, right now?

Parts and Labor

Let’s say you want to build a house in America. Congratulations. You’re going to need a lot of wood. Also, plastic, concrete, steel, glass, and maybe some porcelain tile. Unfortunately, no matter where you live—red state or blue state, the city or the sticks—material costs are rising. Even before the pandemic kinked global supply chains for metals, the average cost of wood, plastics, and composites (for things like railings and paneling) had doubled from 2008 to 2018.

Next, unless you plan on building the whole thing yourself, you’re going to have to find some construction workers. This is where the real trouble starts. The construction sector hasn’t hired enough people to keep up with housing demand in this century. Nearly one-third of construction laborers—and an even higher share of painters and paperhangers—are immigrants. But thanks to anti-immigration policies and the pandemic, annual immigration to the U.S. has fallen from about 1 million to 250,000 in the past five years. What’s more, the housing crash wiped out all sorts of specialists. Since 2006 in California, the number of tile installers, carpenters, and rebar workers has declined by 23 percent, 30 percent, and 52 percent, respectively.

Labor also helps account for why construction costs can vary significantly by area. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly wage of construction workers in New York and Chicago is about twice as high as in rural New Mexico or Texas. Even within a state such as California, local rules like “prevailing wages” (which set a floor for construction wages in government projects) can significantly affect the cost of labor.

The Rules

When you think of housing rules, you might immediately think of zoning. Cities and local governments will carve up an area into little blocks of land, or zones, and create specific rules about what kind of land use, or construction, or ownership is permitted there. One can zone for single-family houses or apartments, for short buildings or tall buildings, for museum-esque preservation or for “mixed-use” development that combines ground-floor retail and apartments. Though nothing is innately unethical about creating a rule for a particular parcel of land, the legacy of zoning in America is fraught. U.S. cities have used zoning laws to segregate white and nonwhite people, to make it near-impossible to build apartment buildings in high-income areas, and to discourage new construction.

In America’s most expensive housing markets, reformers often focus on the need to “upzone” neighborhoods to build taller. But other rules might be even more onerous. As the urbanist Brian Goggin wrote in 2018, some cities have permitting processes with dozens of stages, which can take hundreds of thousands of dollars to get through. When UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation interviewed developers and construction workers about the costs of building in San Francisco, everybody agreed on only one point: “The most significant and pointless factor driving up construction costs was the length of time it takes for a project to get through the city permitting and development.” The average San Francisco project takes nearly four years to be permitted.

One by one, each rule has its reasons. Design and building-code requirements can keep buildings safe and neighborhoods uniform and beautiful (in the eyes of some). Historic-preservation rules can protect a neighborhood’s sense of tradition. Local hiring requirements and prevailing wage rules can promote work for locals and set a wage floor for low-income workers. Parking requirements can ensure that people can access new stores or apartments. With development fees, local governments can directly benefit from new construction by collecting funds to be used for things like sewers, schools, or roads.

These rules might not sound utterly diabolical. Who’s against money for schools? Who’s against safe low-income housing? No one, perhaps. But when you add them up, defensible rules can become indefensible barriers to new construction.

This is especially true for affordable-housing projects, which depend on many different financing sources and government agencies. The Terner Center estimates that these projects in California cost $48 more per square foot than market-rate projects. That’s an extra $48,000 to build each typical apartment of 1,000 square feet, or nearly $4 million extra for an eight-apartment building. What happens when affordable housing isn’t affordable to build? You get less of it.

The Local Vetocracy

Let’s say you’re a developer. You find an empty lot in a major city. You propose to build a big apartment building on the cracked concrete, with dozens of units set aside for people experiencing homelessness. When you ask around the community, people tell you they love the idea. More housing, less homelessness. Who could possibly say no?

The answer is: one angry, litigious neighbor. By filing an environmental lawsuit, this single person can delay construction for years by demanding that the planners conduct expensive and time-consuming research on the ecological impact of new development.

This isn’t a hypothetical. As the author and city planner M. Nolan Gray wrote in The Atlantic, it’s the story of a housing dream deferred, at the corner of First and Lorena Streets in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the past few decades, Gray said, California’s environmental rules—particularly the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA—have allowed citizens to veto new projects by dragging developers to court and saddling them with hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees and environmental research. “CEQA lawsuits have imperiled infill housing in Sacramento, solar farms in San Diego, and transit in San Francisco,” he wrote.

Researchers sometimes call this phenomenon “citizen voice.” Because I’m fond of both citizens and voices, I don’t like this term. I prefer vetocracy—rule by veto—which is Francis Fukuyama’s phrase for systems that empower minority objectors to stop anything from happening. Local vetocracy sounds appropriately vomitous to describe this situation.

Local vetocracy is expensive in two ways. It not only limits the supply of housing but also raises the cost of building. Interstate-construction costs tripled from the 1960s to the 1980s, even after adjusting for inflation, according to research by the George Washington University professor Leah Brooks and the Yale Law professor Zachary Liscow. Basic costs, such as labor and materials, didn’t explain the increase. But the researchers found suggestive evidence that CEQA and other environmental laws passed in the 1970s empowered citizens to veto new construction projects, which “caused increased expenditure per mile,” Brooks and Liscow concluded.

Just as many housing rules are mildly defensible in isolation, you might say there’s nothing wrong with people offering feedback on construction that will affect their neighborhood. Isn’t this just democracy in action? Well, no. Democracy is government by the people—all of them. By contrast, local vetocracy is government by a very small group “yelling loudly with [their] lawyer on speed dial,” as the The Atlantic’s Jerusalem Demsas put it.

When you turn over governance to the most litigious shouters, you implicitly allow older and richer homeowners to block construction for younger, poorer renters. That’s not a recipe for housing abundance. It’s a recipe for the status quo.

The Stagnation

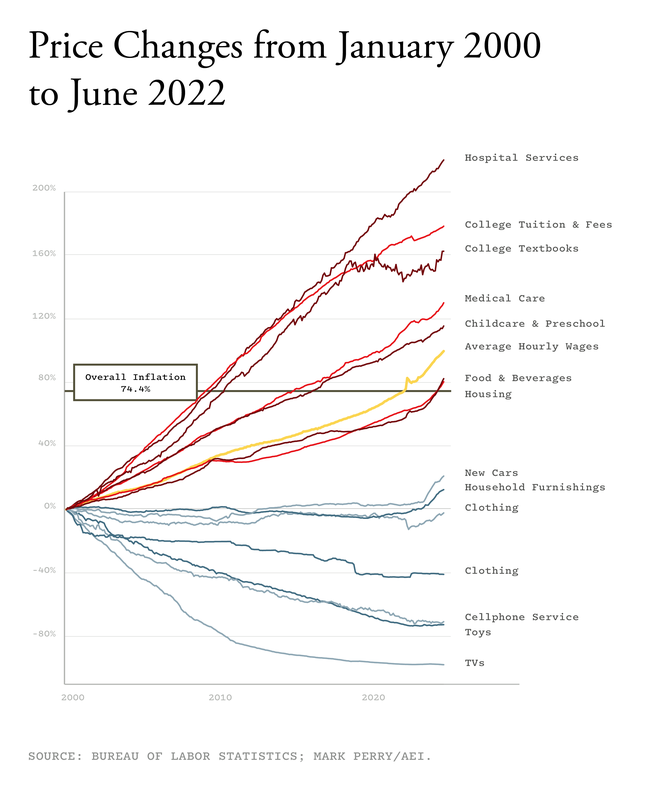

In the past half century, prices for TVs, electronics, computers, toys, clothes, and even cars have fallen in inflation-adjusted terms. But housing prices haven’t. Nobody has figured out how to do for housing what Henry Ford did for cars or Samsung did for flat-screen TVs.

Around the world, construction appears to be one of the only commodity-producing industries that isn’t getting more productive. The Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon has estimated that the construction industry recorded negative productivity growth around the turn of the century in both the U.S. and Europe due to a decline in “multifactor productivity,” which is a complicated proxy for innovation.

Why is innovating in housing construction so hard? Maybe people are just weird about houses, in that they’re happy to buy the same iPhone as everybody else but they want a home that looks unique. (Snooty people who say they hate “cookie-cutter” condos still buy Rolex watches and luxury cars that are mass-manufactured by the zillions.) Relatedly, maybe changing fashions impede lasting productivity gains. (Open kitchens might be cool today, dowdy tomorrow.) Maybe the different rules around the country make construction innovation unattractive, because you might end up designing a housing part that’s useful in Raleigh but illegal in Seattle.

“I think the simplest, high-level way of explaining the lack of productivity [is] it’s hard to make money trying new ideas in construction, and strategies that improve productivity in other industries don’t really seem to work in construction very well,” Brian Potter, whose Construction Physics newsletter analyzes the building industry, told me. Innovation thrives when entrepreneurs can experiment cheaply and fail without too much catastrophe. In housing, experimentation is expensive, and design failures can be fatal.

I asked Potter whether videos of super-fast apartment-construction projects in China suggested that other countries might be cracking the code of housing innovation. Many of these videos feature the company Broad Sustainable Building. “Just because it’s fast doesn’t mean it’s productive,” he said. “These things basically work by just throwing a huge amount of resources and labor at the problem. If you watch the buildings going up, they’re using, like, three to four cranes at once just to keep things moving.” Companies such as Broad Sustainable Building might achieve a breakthrough in construction technology someday. But for now, they’re basically doing normal stuff on fast-forward.

***

Housing is held up not by one bottleneck but rather by several very different kinds of bottlenecks: material-cost inflation, anti-building rules, NIMBY attitudes, and barriers to innovation.

With that in mind, here are some solutions for each bottleneck:

- The U.S. can do only so much to change the global price of lumber. But we do have control over our immigration policy. Right now, low levels of immigration are constricting our construction capacity. More immigration would improve the construction labor pool and, perhaps, improve the innovation labor pool as well. We should welcome bright young minds who can try to solve the problem of stagnation.

- Lawmakers should end single-family zoning, which makes building duplexes and larger apartments illegal. But when permitting takes several years and costs several hundred thousand dollars, you can’t expect a sudden explosion of new construction. So lawmakers should also make development faster and easier. For example, Minnesota’s housing-finance agency streamlines the permitting process by allowing developers to fill out a single application for multiple agencies and funding resources. The newsletter writer Potter also advocates for a state-level cap on maximum time to review building permits.

- As Demsas and the transit-costs researcher Alon Levy have reported, some European countries don’t let loud, angry neighbors demand infinite environmental reviews. For example, French building agencies conduct environmental studies in-house and don’t open the door to citizen lawsuits that can stymie new development. When construction policy is left to the loudest neighbor, the common answer to new units is no. But when the state is in control, it can serve the broad public’s need for more housing.

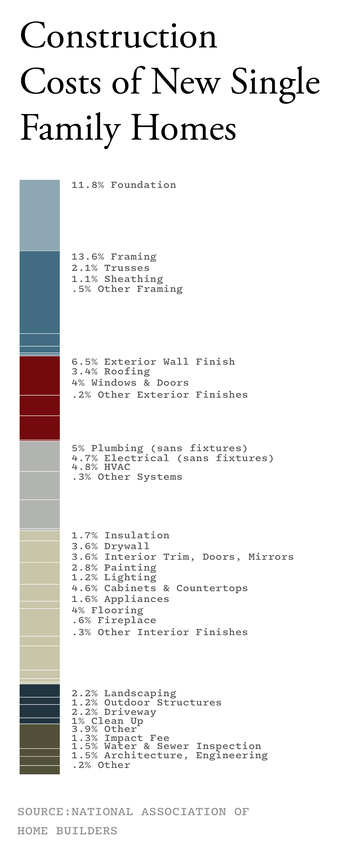

- Housing construction is so complicated—the framing, the HVAC, and the interior trims are entirely different processes—that no single general-purpose technology will immediately make construction more productive. But there might be lots of little silver bullets. For example, the construction-robotics company Canvas has revealed a robotic drywall system that looks promising. Drywall is only about 4 percent of the cost of building a new single-family home. But with 25 Canvas-style companies working on 25 different parts of the construction process, we could really get somewhere.

So the short answer to the question “Why is it so expensive to build a house in America?” is: There is no short answer. Housing costs are complex because nearly half the cost comes from local rules and preferences rather than just materials and labor. That’s appropriate, in a way. A house is not just a pile of wood and stone and work. It is a depository of our values. America’s housing system could prioritize abundance—more houses, permitted faster and built cheaper. Instead, by putting rules over outcomes and litigation over public benefit, we are getting fewer houses, interminable permits, and expensive projects. As in health care, energy, and scientific research, the failures of U.S. housing policy aren’t mysterious error codes. They’re design flaws. This is what happens when a bad blueprint is built to plan.

Want to discuss more? Join me for Office Hours August 9 at 11 a.m. ET. I’ll continue to hold office hours on the second Tuesday of each month. Register here and reply to this email with your questions about progress or the abundance agenda. If you can’t attend you can watch a recording any time on The Atlantic’s YouTube channel.