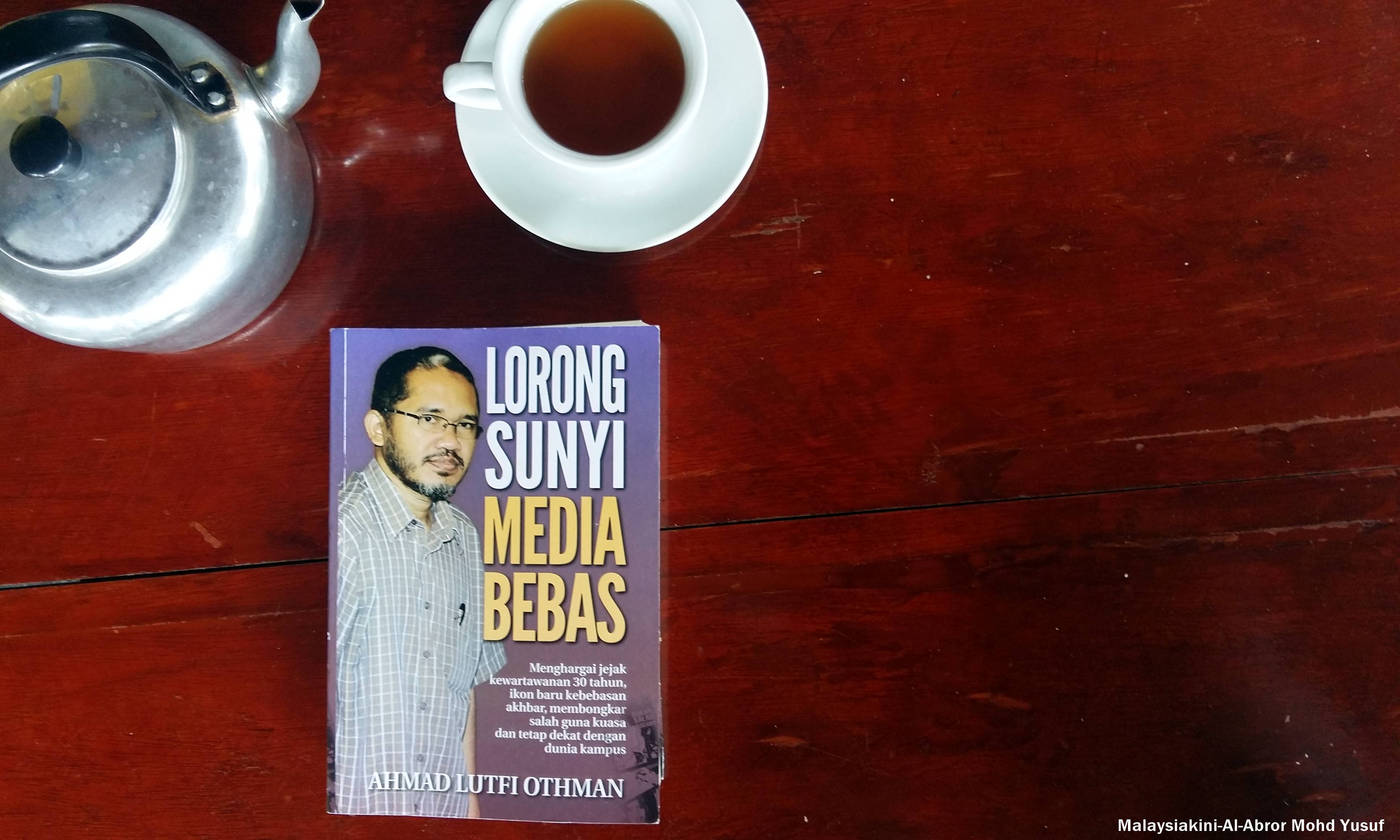

Ahmad Lutfi Othman, died yesterday just after turning 59. A fighter for media freedom during the heydays of reformasi, Lutfi served two stints as Harakah editor before the PAS organ was taken over by conservative forces within PAS. This article was written in 2013.

Ahmad Lutfi Othman never stops surprising me.

When I interviewed him for the first time in July 2013, I was so surprised by what he said that I asked if we could meet again, just to be sure I had understood properly.

I was working on a study of journalism and Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia. I was interested in Harakah because it's the newspaper of PAS, the Pan-Malaysian Islamic party.

I first met Lutfi during a training I was doing at Harakah Daily online. I had previously met Lutfi's counterpart, Zulkifli Sulong of Harakah Daily, during a conference at the Universiti Malaya, and was teaching a narrative writing workshop at the online news portal. After the first day of the training, several of the reporters who were there said that I had to meet "Cik Lutfi."

Before I met Lutfi, I asked about him at Malaysiakini, where I was also doing research. Although I can't remember his exact words, Malaysiakini's editor-in-chief Steven Gan said something to the effect of how Lutfi was a great man, and that I had to meet him.

"He's a fearless fighter for press freedom," Steven said. "Ask him about the newspaper that he kept publishing each month with a different name in order to stay one step ahead of the Home Ministry."

I was intrigued. Who would have thought that the editor of PAS' newspaper would be described as a fearless fighter for press freedom?

So my friends arranged a meeting.

I remember being quite nervous before we met. Zulkifli I already knew, and the jolly, bespectacled editor of the daily was my friend. We had met and talked several times about his view of journalism and Islam, and what he was trying to do with the online edition.

I got to the office a bit early and met my friend Arif Atan, who took me up to the third floor. As at the daily, we left our shoes in the hallway. Arif turned on the air conditioner in the conference room, and we waited for Lutfi to arrive. Several other journalists drifted in.

Harakah's building is in an older shopping centre off Jalan Pahang Barat, not far from the Titiwangsa LRT stop. The meeting room has one glass wall, a big table, and about 10 red chairs. It smells faintly of room freshener. One wall features a framed issue of Harakah's pull-out section Fikra, with photos of PAS leaders Nik Aziz Nik Mat and Abdul Hadi Awang and headline readings "Islam Asas Kekuatan PAS," and "Kezaliman belum berakhir."

The conference room is a bit shabby, with worn carpet and newspapers piled up in the centre of the table. A whiteboard takes up one end of the room, with the word "Harakah" in red letters. On Tuesday, the morning after deadline night, the office is quiet.

Lutfi arrived at about 11am. He was wearing a purple shirt and silver-rimmed glasses, and he walks with a cane. His hair is silver, and he has a short goatee. The reporters seemed worried about him. One explained that he had been up very late working the night before, and that he wasn’t well. Heart troubles, diabetes, kidney problems – they said that he had recently spent a lot of time in the hospital. Given all of this, I was surprised by his energy. About 50 years old, he has an easy laugh and eyes that twinkle behind his glasses.

During that first conversation, which lasted for several hours, he told me of his history at Harakah, his dream of independent media in Malaysia, and his view of the relationship between journalism and Islam. I was impressed by his thoughtfulness, his intelligence, and his kindness. My Malay isn't as good as my Indonesian, and after a few sentences, I noticed that he had switched to Indonesian, using words that I could understand.

Lutfi tells me that he was born into a family that was "all PAS," and that everyone in his kampung belonged to the Islamic party. "If there were Umno members, they didn't want to admit it," he laughs.

"Since the time I was little, my family, my father, always emphasised the importance that as a Muslim person, in our entire life, Islam has to be followed. By our worship, our ritual, praying, fasting – even the issue of politics."

In Malaysia, there is only one Islamic party, so even if its leaders were "not perfect," Lutfi believed that he had no choice but to follow it.

"If there is only one Islamic party, and if there is a problem in that party, then it is my jihad to straighten it out from the inside," he says. "Freedom of the press, this is only one part of the larger struggle of Islam."

"I don't see Islam as opposed to press freedom," he adds. "Because for me, the issue of responsibility, the issue of assertiveness, of justice itself – these are the bases of Islam that have been passed down. Opposing tyranny, defending those who are oppressed, this is the true mission of Islamic freedom."

We speak about Harakah's history, and how he had joined it shortly after it was founded in 1987.

"During those 26 years," he said, "I entered and left Harakah maybe four times. I left, I came back. I left, I came back."

But why did Lutfi leave Harakah so many times? Because he wanted to have his own publication.

"I was a young spirit, oriented towards real politik," he said, "and at that time, I wanted to operate media on my own that could be more free."

"Harakah, as a party organ, had many regulations, guidelines, and I as a journalist cum publisher, I wanted to own my own company that could be more free."

"This was why I entered and left," he added. "But each of the four times I left, my connection with Harakah was still intimate."

In 1998, during one of the times he left Harakah, Lutfi did establish his own magazine, Detik, which he began with Fathi Aris Omar, who is now at Malaysiakini. He named the bi-monthly in honour of Detik magazine in Indonesia, which had been banned by Suharto along with Tempo and Editor in 1994.

Battles with Home Ministry

During the 17 years that I have been doing research on journalism in Indonesia and Malaysia, I have met many editors who talk about press freedom, but I have never met one who is more committed to it than Ahmad Lutfi Othman. His battles with the Home Ministry over getting a press permit have become legendary. He explained.

"As a journalist, from the very beginning, since graduating from university, I had requested a permit from the Home Ministry. I think I had requested that permit maybe 100 times. Not only was it never granted, but I was never even interviewed, or asked about issues connected with it. I was only refused, just like that."

With Detik, Lutfi wasn't the owner, but rather the publisher with a borrowed permit. And that permit had to be renewed every three months. If your permit wasn't renewed, you were banned.

After the results of the 1999 general election were announced (Dr Mahathir Mohamad retained power in the wake of the sacking of his deputy, Anwar Ibrahim), Detik's permit was recalled, along with those of any other Malay-language publications that were considered to have helped the Barisan Alternatif. This was how Detik was banned.

Although Harakah newspaper didn't lose its permit, its editors were also informed that the party organ could no longer be published twice a week, but only twice a month.

Lutfi explains what happened next. "Even though Detik was banned, I still had a staff of more or less 15 people, and an office for which I was responsible. So I put out a newspaper. It was a tabloid - it looked like Harakah - but each time the name was different. I published it twice a month.”

Lutfi says a few words to his secretary, and in a few minutes, he returns with a pile of papers: Warta, Kritis, Protes, Alternatif, Gerak, Memo, Bebaskan, Oposisi, Amanat, Memo 22, Memo 2, Memo 3 - there are dozens of them! I laugh as Lutfi piles the papers up on the table and I read the names. Later I learn that there were about 50 of these publications.

It is clear that Lutfi doesn't give up easily.

He explained how his biggest worry was for the distributors, who could be fined up to RM10,000 for a RM2 sale, and a commission of 20 cents on each newspaper sold. "My distributors," he said. "They were the ones who were afraid."

For Lutfi, it is sad that there is so little media activism in Malaysia.

"Why is that?" I asked. His answer pointed to the lack of independent media, and to the problem of ownership.

"Because Detik had been banned, the only thing I had left was my tabloid newspaper that I was publishing without a permit, and Wasilah magazine - a magazine for teen women. So the fewer people who worked for me, the fewer people there were who were working for free media, and the fewer people who wanted to become activists.

“Throughout this time I tried to meet with colleagues from mainstream media: Utusan, Berita Harian, and media owned by Bernama. But they had no desire to struggle. For them, these matters weren't relevant. First, they weren't directly concerned, and second, if they were concerned, they were connected with a company or a council that wasn't going to approve of this kind of activity."

After Detik was banned in 1999, Lutfi and Fathi established KAMI, Kumpulan Aktivis Media Independen. They met with Suhakam, the Malaysian Human Rights Commission, and presented a memo of their demands.

Yet even this was difficult. With a rueful laugh, Lutfi tells the story of how when he and his friends made a coffin to commemorate symbolically the death of independent media, they couldn't find even four people to carry it.

Getting serious again, Lutfi explains, "I feel that political people in general, no matter from what party or background, in general they don't like independent media. And no matter what party, before it becomes the government, media freedom is one of the issues they strive for.

“But actually, it is pretty difficult for them to implement, if their thinking isn't truly open, if they don't have a genuine understanding of democracy, and when they see that their power could be hurt, that their own power could be threatened.”

For Lutfi, if citizens don't continue to work together and to push for change, media freedom won't happen, regardless of who the party leaders are, or which coalition is in charge.

"Once, during a programme to launch my book," he says, "there was a colleague who asked me what do you hope for if PKR becomes the government? Rather openly, I said that for me, although I am a person who has long worked for the party organ of PAS, don't ask me what I hope for with independent media. For me, even with a new government, each citizen has to continue to demand the implementation of what we dream."

Islam and media freedom

When I suggest that maybe part of Lutfi's role at Harakah has been to educate the PAS leadership about the importance of independent media, he laughs. "As ordinary human beings, ordinary politicians, it's difficult for them to hear criticism," he says.

Yet Lutfi is also quick to explain why some PAS politicians are frustrated with Harakah, and want it to focus less on Pakatan Rakyat and more on the party itself.

In Malaysia, he says, where there is no media freedom, and where the government has many outlets but PAS has only one, there is a sense of "why do we have to give space to material that can quote-unquote hurt us? I can understand that. I try to understand their concerns, and I think they also try to understand what I struggle for."

We speak a little bit about Malaysiakini, which he also follows. We agree that whereas Steven Gan only has to think about journalism, Lutfi must also keep in mind not only the needs of the party, but also the teachings of Islam.

"I am in Harakah also as a responsibility to religion," he says. For religion, Harakah reporters will accept lower wages and allowances, and also higher expectations.

"I actually see that the teachings of Islam and the concept of media freedom are not very different from the principles of journalism," Lutfi says.

"We are guided by the truth - this is always our aim. Our journalism is based on the hadith that are given by the Prophet Muhammad. First, if there is any doubt at all about the truth of a story, however small, the story must be refused.

“And second, if a person comes bearing news, if it is felt that there is a problem with that person's character, especially if he is a trickster or a liar, then he must be refused. These are two teachings of the Prophet.”

For Lutfi, the "right of reply" is important within the context of justice, especially for opposition leaders who are denied a place in the mainstream media, who are criticised, and who are never given space to answer. From this perspective, he notes, Harakah has to give them space.

And finally, there is the issue of morality. "We aren't going to publish what we don't believe," he says. For example, in the world of entertainment, if there is a singer who appears with a group of Muslims, and she is not wearing a tudung, "Harakah will give her one."

On the other hand, there is the issue of openness, even a kind of pluralism. "PAS needed for a long time to open the party to non-Muslims, and I believe that these changes are going to happen,” he says.

“It is not a change in religion, religion stays the same. But in terms of interpretation; how we see ‘real politik.’ How we see environments that are maybe different. And for me, this is one development that is very positive."

It bothers Lutfi that it is Western nations that always come out on top in world rankings of democracy, transparency, and media freedom. Why, he asks, are nations that are not especially “Godly” ranked higher than nations that are “Islamic”?

"We have to have this as a target. That doesn't mean we have to leave behind things like hudud, clothing, things like that, but the issue of poverty, why are Islamic countries at the bottom? From the point of view of religious principles, it is something that has to be emphasised, and I always feel that it is my responsibility to educate.

“And I feel that press freedom is the key to it all, the key to democracy, the key to wipe out poverty, the key to reduce the gap between rich and poor."

Professionalism in media is Islamic, according to Lutfi.

"I see that journalism or the management of media that is professional is Islamic," he says. "The name of my column I took from ‘Catatan Pinggir’, from [Tempo magazine’s founding editor] Pak Goenawan Mohamad. So although Tempo can be seen as a group that is pretty liberal, I think there are several important matters on which there is no difference.”

“On liberal Islam, we can cooperate. We don't agree with everything, but we don't have to agree with everything in order to be able to work together,” he added.

‘We have to struggle’

Lutfi dreams that if Pakatan should ever win, there will be no need for permits. “Publications that disagree with us will be allowed to publish,” he says. “Utusan can continue! The Star can continue.”

When the weekly magazine The Heat was suspended by the Home Ministry at the end of December 2013, over alleged violations of the terms of its publishing permit, there was hope that maybe this would be the tipping point, that perhaps Malaysia’s journalists would finally decide that enough was enough.

Another movement was organised, and there was a town hall meeting at the Chinese Assembly Hall. Lutfi was there.

"We have to struggle, we have to be serious to develop a media system that is free," he said. "But until then, we still need this space [Harakah].”

Ahmad Lutfi Othman never stops surprising me.

He never stops inspiring me, either - not only as a writer and an editor, but also as a person who struggles to reconcile his faith with his work.

Lutfi has big dreams for Malaysia, and for a day in which media will be truly independent. But until that day comes, he is very much living in the here and now.

"I continue to feel that although there are sometimes big problems within the party," he says, "between religion, politics, press freedom - I see this as a process. And as a Muslim, I am certain that each process, or even each problem that I face, is going to be evaluated by God as a sign of piety.

Therefore, this becomes a motivation for me."

JANET STEELE is an associate professor at the School of Media and Public Affairs at the George Washington University. She is the author of ‘Wars Within: The Story of Tempo, an Independent Magazine in Soeharto's Indonesia’.