As a freelancer and journalist of color, I use many sources to find jobs, but the Writers of Color account on Twitter has become one of my favorite go-tos. Besides posting jobs and pitch calls, the account cracks jokes about media’s pervasive whiteness, the perils of the media industry, and — most notably — polite-shames publications that don’t disclose pay rates.

When the deputy news editor of a big science publication recently refused to share the outlet’s pay rates in a lengthy thread on Twitter, igniting backlash from many, the Writers of Color account chimed in: “refusing to share rates is a bad policy which hurts writers of color.” (The editor has deleted the thread and created a new one with screenshots of his original tweets).

If you’re a follower, you’ll know that is a typical tweet the account sends to editors, who frequently tag the group hoping their open jobs and pitch calls reach more diverse writers. But editors often neglect (or, as the above example shows, refuse) to disclose how much these opportunities pay. It’s a problematic practice that is unfortunately still pervasive in media. Writers of Color, for its part, is holding recruiters accountable by posing the most basic of questions: how much does it pay?

*sad trombone*

— Writers of Color (@WritersofColor) July 23, 2021

As Jazmine Hughes, one of the journalists behind Writers of Color, tells it, the project was conceived when Hughes and fellow journalist Durga Chew-Bose were commiserating over the “inability — or unwillingness, tbh — of editors to find writers of color for their publications.” The solution was clear: if editors weren’t going to be proactive about recruiting more diverse talent, the group would do it for them.

Along with Vijith Assar, John Erik “Buster” Bylander, and Bijan Stephen, they created the Writers of Color website, a database of non-white writers with expertise covering various topics. When the initiative launched in 2015, there were roughly 700 people listed in the database. Today, the group’s project has expanded to social media with over 67,800 followers on Twitter. (The group declined to be interviewed for this article.)

As the group’s online presence has expanded, its advocacy has also moved beyond just representation. Kenneth Seward Jr., 37, a Black writer who covers video gaming and film and follows Writers of Color, says the account has encouraged more transparency. He recalls discussions about unequal pay between writers of color and white writers in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests last year. “We saw that a lot of the white editors or white writers got paid more than people of color, in some cases drastically more,” Seward, Jr., recalled. “And it was like, wow.”

Writers of Color’s M.O. of badgering publications about how much they pay has become so well-known that some job posters preemptively post their compensation, in an attempt to avoid public dragging.

look at @vice over here how-much-does-it-pay-ing itself https://t.co/wG7ueMjzEA

— Writers of Color (@WritersofColor) July 22, 2021

As the push for diversity across media grows, studies reveal race- and gender-based pay inequities inside newsrooms. A 2018 study by the Los Angeles Times Guild showed women of color experienced the largest pay gap in their newsroom, earning on average less than 70 cents for every dollar earned by a white man. Another by the Washington Post Guild also discovered employees of color were paid less than their white counterparts, even when they had more experience, with women of color receiving $30,000 less than white men.

As a freelancer myself, I know firsthand that pay inequities also persist for us. Freelance journalists do not have the support of a union, so we must negotiate the worth of our work each time we pick up a new assignment. That becomes difficult when we don’t know an outlet’s average pay rate which, once revealed, can sometimes show biases through disparate compensation offered by the same publication.

Doris Truong, director of diversity and training at the Poynter Institute, says pay transparency helps hold publications accountable, both by outside parties and internally. “You are going to have to be able to quantify why somebody is getting paid more,” Truong explained, “and it might be that somebody who has 20 years of experience is getting paid more than somebody who is in college, but I think you want to be able to explain why that [pay disparity] is.”

— From AJ with ♥️ (@fromajwithlove) April 9, 2021

Conversely, if a hiring manager is aware their publication is on the lower rung of pay compared to others, Truong said they might want to consider adjusting their rates to be more competitive.

For freelancers, pitching a story without knowing whether it’s worth the time is a gamble since time is money, especially for writers of color. “If I’m a Black writer — and my time is very valuable, just like everybody else’s — but I have all these other obstacles put in front of me, [the Writers of Color account] showing the pay first, it kind of removes one extra barrier,” Seward Jr., the video game writer, said.

Young journalists of color are particularly susceptible to unfair pay practices. The industry’s notoriety for offering unpaid internships on promises of prestigious bylines and “exposure” can greatly impact young writers from diverse backgrounds, who are often recruited into lower-level positions like internships and junior staff positions.

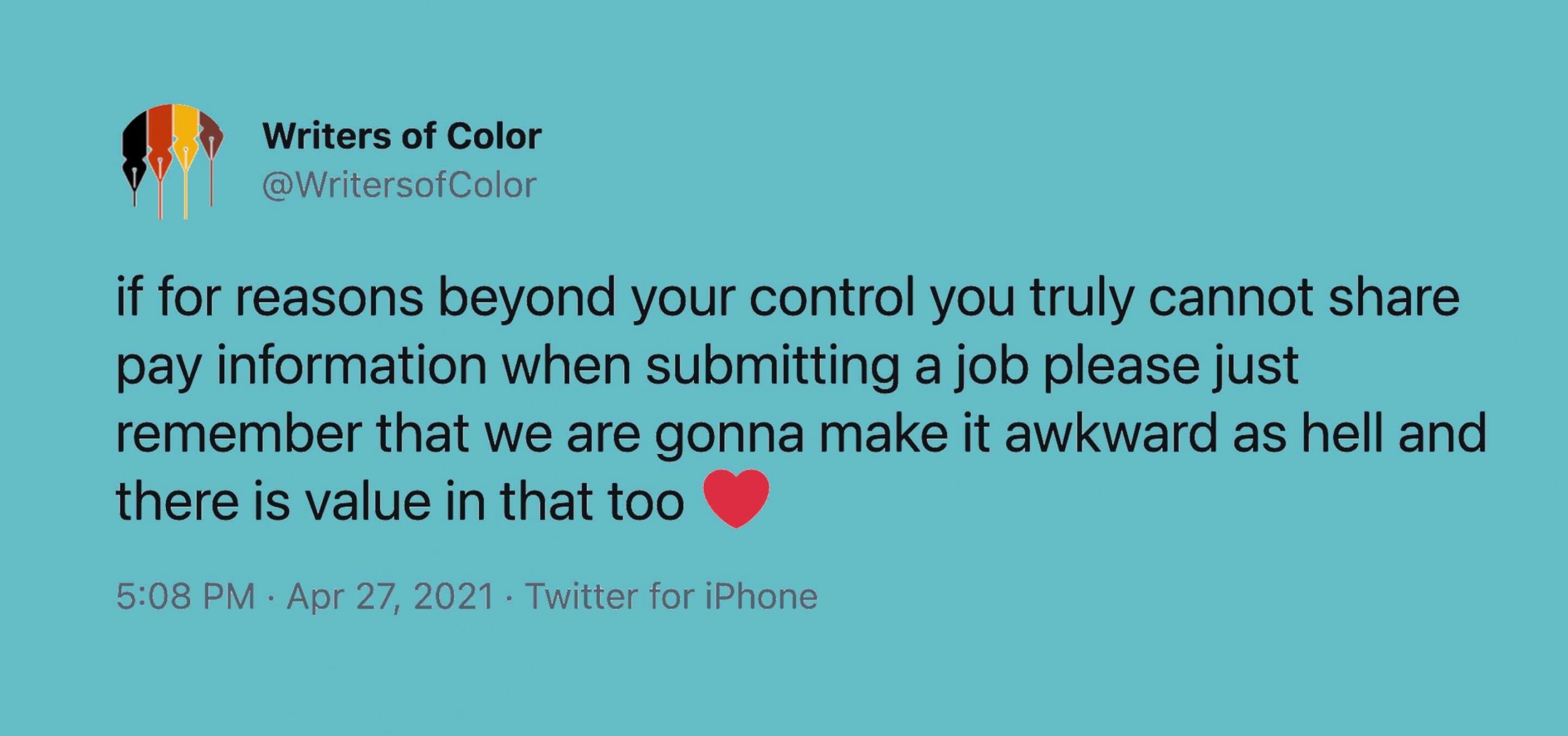

if for reasons beyond your control you truly cannot share pay information when submitting a job please just remember that we are gonna make it awkward as hell and there is value in that too ❤️

— Writers of Color (@WritersofColor) April 27, 2021

Jae Thomas, 22, a queer nonbinary food and lifestyle writer with Thai-Mexican roots, had unpaid internships at a number of publications under legacy media company Hearst before landing a fellowship at Mashable. Thomas says unpaid internships negatively impact students of color.

“I was getting help from my family but I still was working one or two other jobs on top of being a full-time college student, which definitely negatively affected my grades,” they said, “and my ability to maintain a social life because I was so worried about money all the time.”

Thomas has used the Writers of Color account to help with their job hunting and says the account’s increasingly assertive and often funny methods to push publications into disclosing salaries and pay rates shows that everyone can play a role in advocating for real change.

“I think Writers of Color is really pushing for [equity and diversification] and showing that it doesn’t have to just be left to the media companies to run things,” Thomas said. “Freelancers and staff writers and all people of color should have a voice, and can have a voice.”

Natasha Ishak is an international journalist from Indonesia based in New York City. She previously wrote for Nieman Lab about the Atlanta spa shootings.