A declaration of gratitude and humility, the Christian anthem Amazing Grace is sung around the world at significant moments. The stirring lyric sometimes expresses a sense of loss, yet equally often a shared hope for the future.

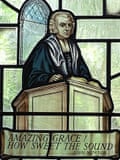

The song, familiar as the soundtrack to social protest, is also closely associated with the arrival of the new year, and its verses were first heard in public 250 years ago on 1 January in the small Buckinghamshire town of Olney, near Milton Keynes. The lyric, thanking God for enlightening a sinner, was originally part of a sermon written for New Year’s Day 1773 by the Rev John Newton, a repentant former slave trader who presided over the congregation at the Olney church of St Peter and St Paul.

Now a major new orchestral and choral piece entitled Forever will be performed in recognition of the landmark anniversary. The collaborative project, being created by leading black and ethnically diverse British talent, aims to celebrate the international resonance of Amazing Grace.

In the 20th century, the hymn earned a special role in the American civil rights movement, despite Newton’s links to slavery. Now the award-winning poet Rommi Smith is writing the libretto for music composed by the leading operatic baritone Roderick Williams. Their piece will be premiered this summer by Britain’s much-garlanded Chineke! Orchestra as part of the Milton Keynes International Festival.

“It is a hymn that seems to always have been there, but it has special resonance for me because I have specialised in writing about civil rights,” said Smith.

Newton worked on a series of hymns in Olney with the poet William Cowper, and the duo are a key part of the cultural heritage of the area. The town’s Cowper & Newton Museum has helped Smith with her research following her commission last summer, when The Stables, Milton Keynes’ theatre and music venue, approached her to write the libretto.

Smith plans to explain the wider impact of Amazing Grace, which is still such a standard in America that it accompanied the 2020 funeral of George Floyd, the victim of police violence whose death sparked worldwide protests. It was also sung by US President Barack Obama at the 2015 funeral for one of the victims of a mass shooting at a Charleston church.

“Our new musical piece will reflect on all that,” said Smith. “I want to look at the song’s enduring properties and its reach, as well as at the puzzle of Newton’s slave trading past.”

The tune that most people know, arranged in 1909 by the American music publisher and composer EO Excell, is one of several the lyric was first set to. Today, the many versions of the popular tune, whether sung in the gospel style, in a rowdy pub, or by a great soul diva, have given it a layered series of meanings.

“Black Americans have claimed it, with versions by Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson and Whitney Houston, each re-authoring it with their singing,” said Smith. “These performances, particularly the live ones in front of an audience, often have ad-libbed lines, or added jazz scatting, about issues of the moment.”

Newton’s own life story certainly lives up to the emotional rollercoaster of his powerful lyric. Born in Wapping, east London in 1725, his unhappy childhood at home and boarding school was followed by a career on the high seas. Press-ganged into the navy, he survived hardships at sea and also built up a reputation among shipmates for writing obscene rhymes. Then came an enforced period as the crew of slave ship and the beginning of a lucrative career investing in the trade.

Newton even briefly suffered a period of a slavery himself, held in bonded service to a high-ranking member of the Sherbro people in what is now Sierra Leone.

His religious conversion came in 1748 at the end of a stormy voyage back to England via Ireland. The level of his evangelical conviction then prompted friends to suggest he join the English clergy.

after newsletter promotion

Piecing together all the implications of this backstory, Smith has focused on the responses to a succession of interviews with refugees, activists, members of the clergy, asylum seekers, church-goers and some of the black residents now living in the area around Olney, as well as with contacts in Sierra Leone.

What was clear, Smith said, is that the hymn is seen as a kind of musical sanctuary in turbulent times. “It is regarded as a comfort, which is an idea I have used in the first stanzas I have written, using the imagery of a warm coat, after speaking to some refugees from Ukraine.”

Responses from people aware of Newton’s past in the slave trade came in one of two kinds. Some felt they owned a new, rewritten version of the hymn after hearing modern renditions by artists such as Judy Collins, Jackson or Franklin, while others felt conflicted but hoped that Newton’s eventual rejection of the slave trade meant he had been redeemed.

“Those who look to their faith for redemption saw hope in Newton’s later life, when he gave testimony against slavery in London and became friendly with the abolitionist William Wilberforce,” said Smith.

Even for interviewees with no religious belief, the song seemed to represent both comfort and hope at uncertain moments. “It is a song that holds you steadfast,” concluded Smith. “It is passionate and reassuring at the same time. And we all need reassurance and an answer to the question, ‘Am I on the right path?’”

The subheading of this article was amended on 3 January 2023. An earlier version incorrectly referred to the Chineke! Orchestra as a “black orchestra”; in fact it is comprised of majority black and ethnically diverse musicians. Also Roderick Williams was described as a tenor, when he is a baritone.