Gun Violence and COVID-19 in 2020

A Year of Colliding Crises

Learn More:

Summary

The United States has seen the collision of two major public health crises over the past year: COVID-19 and gun violence. We still don’t fully understand how damaging this collision has been, and we don’t yet fully know how it will continue to affect Americans. But what we do know is the effects have been far-ranging. For one, the pandemic has had a pronounced impact on gun violence in the United States as both homicides and unintentional shootings increased to record levels in 2020.

Introduction

At the time this report was published some 2020 data was still preliminary and not fully understood. For the most recent data on gun deaths in 2020 see Gun Violence in America, EveryStat for Gun Safety, and City Dashboard: Murder and Gun Homicide.

Firearm Deaths and Injuries: 2019 to 2020

Key Findings

- The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the impact of our country’s gun violence crisis. There were 3,906 additional firearm deaths and 9,278 additional firearm injuries in 2020 compared to 2019.

- Cities saw historic levels of violence last year. Three in four big-city law enforcement agencies saw increases in firearm homicides in 2020. And as the coronavirus has rolled across the country, the impacts of both COVID-19 and gun violence have not been evenly felt. Black Americans, while not more susceptible to contracting the disease, are nearly twice as likely as white Americans to die from COVID-19. They are also 10 times as likely as white people to die by firearm homicide.

- Gun sales have surged during the coronavirus pandemic. Based on the number of background checks, Everytown estimates that people purchased 22 million guns in 2020, a 64 percent increase over 2019.

- Unintentional shooting deaths by children increased by nearly one-third comparing incidents in March to December of 2020 to the same months in 2019. The pandemic saw millions of children out of school while gun sales hit record highs, bringing more guns into homes. This resulted in a tragic surge in the number of children accessing firearms and unintentionally shooting themselves or someone else.

- Domestic violence spikes during times of prolonged emotional and financial stress. Stay-at-home orders and reduced capacity in shelters left domestic violence victims trapped with abusive partners. Too many of these abusers had easy access to guns. Data from over 40 states showed about half of domestic violence service providers surveyed saw an increase in gun threats toward survivors of intimate partner violence in their communities during the pandemic.

- Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rise in violence against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community, particularly against AAPI women. Violence against women and the AAPI community, fueled by hate, is made more deadly by easy access to guns.

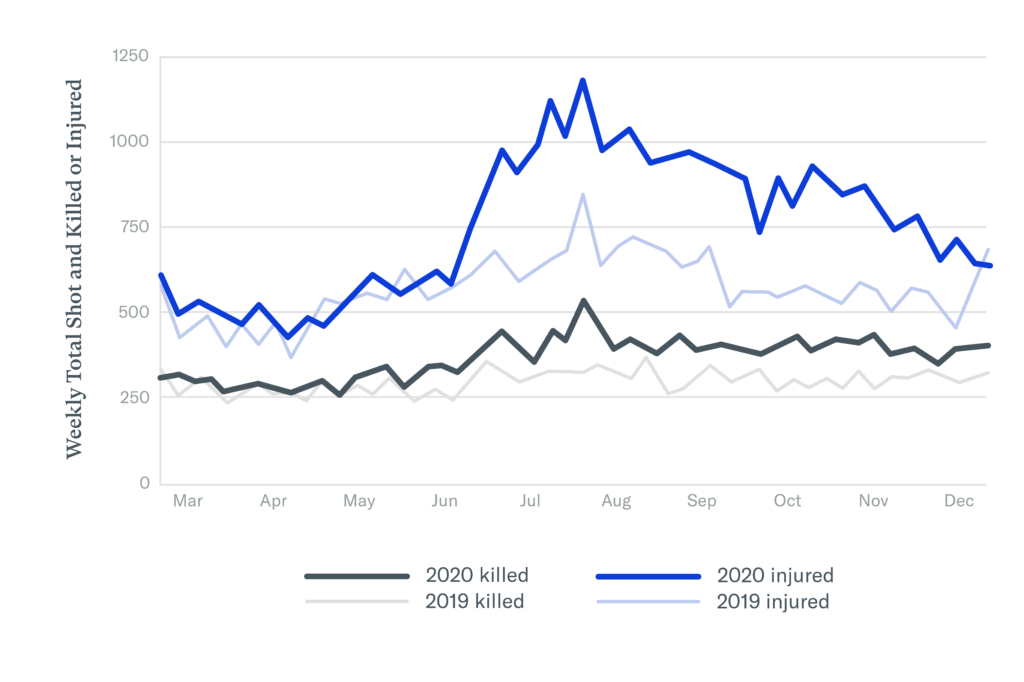

Historic Levels of City Gun Violence

At the beginning of the pandemic, governments enacted shelter-in-place orders and social distancing requirements. There was hope that these measures would not only reduce the spread of COVID-19 but also help reduce city-based gun violence. Yet starting in the summer of 2020 and continuing through the rest of the year, city gun violence surged.

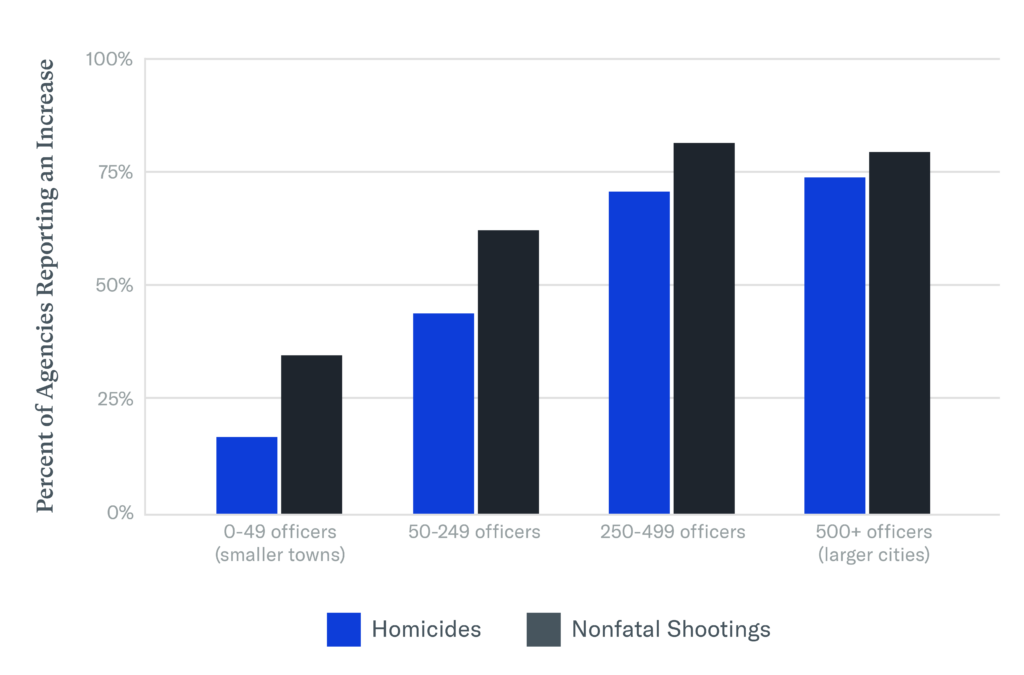

In many cities, the number of people shot and wounded or killed increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2021, researchers surveyed 129 law enforcement agencies representing a diverse set of cities across the United States in terms of size, demographics, and geographic coverage. They found that in nearly 70 percent of these agencies, nonfatal shootings increased, and in 57 percent, there was an increase in gun homicides from 2019 to 2020. This survey also found that the largest agencies—that is, those serving the largest cities—were more likely to report an increase in gun homicides and nonfatal shootings: Nearly three in four reported an increase in firearm homicides and four out of five saw increases in nonfatal shootings.5Police Executive Research Forum, “Daily Critical Issues Reports: Survey on 2020 Gun Crime and Firearm Recoveries,” January 26, 2021, https://www.policeforum.org/criticalissues26jan21.

Law Enforcement Agencies Reporting Increased Firearm Homicide or Nonfatal Shootings, Percent Change Since 2019

One explanation for this rise is that the pandemic aggravated the very factors driving city gun violence. Black and Latino communities have borne the heaviest burden of gun violence in cities for years. Generations of systemic racial discrimination and inequities in health care, housing, education, and other factors have exacerbated the risks of gun violence.6National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, ed. James N. Weinstein et al. (Washington, DC: National Academies Press [US], 2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/. These inequities have also made Black and Latino communities more vulnerable to the devastating effects of COVID-19.7Fatimah Loren Muhammad, “The Pandemic’s Impact on Racial Inequity and Violence Can’t Be Ignored,” The Trace, May 7, 2020, https://bit.ly/2TuMkQ7. In fact, Black people in the United States are nearly twice as likely as white people to die from COVID-19.8“Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity, as of March 12, 2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 18, 2021, https://bit.ly/3bbmB8N. They are also 10 times as likely to die by gun homicide as white people.9Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using five years of the most recent available data: 2015 to 2019. Analysis includes: all ages, non-Hispanic or Latino only, and homicide including legal intervention. The disproportionate impact of both the virus and gun homicide on Black communities reflects and intensifies the United States’ persistent racial inequities and underscores the need for meaningful structural change and for sustained financial investment in previously under resourced communities.

Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 Deaths and Gun Homicide on Black Communities

- The COVID-19 death rate of Black Americans is double the rate of white Americans, despite similar rates of infection.10“Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity, as of March 12, 2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed March 15, 2021, https://bit.ly/3bbmB8N.

- Black Americans are 10 times more likely than white Americans to die by gun homicide.11Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using five years of the most recent available data: 2015 to 2019. Analysis includes: all ages, non-Hispanic or Latino only, and homicide including legal intervention.

Why? Both the pandemic and gun homicide reflect and intensify this country’s long-standing racial inequities in health care, housing, education, exposure to environmental hazards, and more.

Unemployment resulting from the pandemic has also contributed to the disproportionate impact of city gun violence on Black communities. To contain the virus, thousands of businesses temporarily closed, and many of those closures turned permanent.12Chris Arnold, “America Closed: Thousands of Stores, Resorts, Theaters Shut Down,” NPR, March 16, 2020, https://n.pr/2Ttp4C7; Anjali Sundaram, “Yelp Data Shows 60% of Business Closures Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic Are Now Permanent,” CNBC, September 16, 2020, https://cnb.cx/3cX50lJ. These layoffs disproportionately affected Black communities because they are overrepresented in jobs that cannot be done remotely—jobs that needed to be cut as the pandemic worsened.13Graham Rapier, “This Chart Shows Fewer Than Half of Black Americans Were Employed in April, Highlighting How Coronavirus Layoffs Have Disproportionately Affected Black Communities,” Business Insider, June 4, 2020, https://bit.ly/3cSop7p. This kind of economic distress has a significant bearing on all forms of gun violence, as research shows that neighborhoods with high unemployment or high poverty rates have higher rates of gun homicide.14Daniel Kim, “Social Determinants of Health in Relation to Firearm-Related Homicides in the United States: A Nationwide Multilevel Cross-Sectional Study,” PLoS Medicine 16, no. 12 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002978.

Employment opportunities can serve as a critical protective factor in disrupting cycles of violence. Another proven way to mitigate the effects of city gun violence is through funding community-based violence intervention programs. These programs work with individuals at the highest risk of shooting or being shot and help reduce violence through targeted interventions—including job readiness and workforce development programming—in their communities and in hospitals. Despite their effectiveness,15Andrew V. Papachristos and David S. Kirk, “Changing the Street Dynamic: Evaluating Chicago’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy,” Criminology & Public Policy 14, no. 3 (2015): 525–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12139; Caterina G. Roman et al., “Philadelphia CeaseFire: Findings from the Impact Evaluation,” Key Findings Research Summary (Philadelphia: Temple University, January 2017), https://bit.ly/3wz0YI7. these programs are too often underfunded.16Lois Beckett, “How the Gun Control Debate Ignores Black Lives,” ProPublica, November 24, 2015, https://bit.ly/2v1Ftou. Street outreach organizations, in particular, have long been at the front lines of gun violence prevention work in our cities. Now they must battle two public health crises at once, as they also face the challenge of being frontline workers.17David Muhammad and DeVone Boggan, “The Very Essential Work of Street-Level Violence Prevention,” The Trace, April 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/3dhn1dv.

Cities and states are grappling with the financial impact of COVID-19. Despite this, it is imperative that they sustain funding for these critical gun violence prevention programs. Localities can bolster funding for these programs by drawing from the American Rescue Plan. Signed into law in March 2021, the law authorizes $130 billion for local governments to counter the economic toll of the pandemic, which can include investment in violence intervention programs.18Public Law No. 117-2 § 9901; Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “American Rescue Plan for Gun Violence Reduction,” April 5, 2021, https://everytownresearch.org/report/american-rescue-plan-for-gun-violence-reduction/. Support for these programs is an investment in reducing gun violence in cities.

It is imperative that cities and states sustain funding for gun violence prevention programs.

Of course, community gun violence intervention programs alone cannot mitigate the structural inequity that fuels gun violence. Lessons learned from this pandemic include the imperative to invest in the broader resources communities require to be safe and healthy. Long-term interventions include support for community-driven crime prevention by environmental design (e.g., cleaning vacant lots, greening parks, and providing additional outdoor lighting)19Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “Crime Prevention through Environmental Design,” April 28, 2019, https://everytownsupportfund.org/report/crime-prevention-through-environmental-design/. and summer youth employment programs.20Alicia Sasser Modestino, “How Do Summer Youth Employment Programs Improve Criminal Justice Outcomes, and for Whom?,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 38, no. 3 (2019): 600–628, https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22138. Counseling and mentorship services for youth21Ellicott C. Matthay et al., “Firearm and Nonfirearm Violence after Operation Peacemaker Fellowship in Richmond, California, 1996–2016,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 11 (2019): 1605–11, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305288. and cognitive behavioral therapy22Sara B. Heller et al., “Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chicago,” Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2015), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21178. are also proven to help reduce violence.

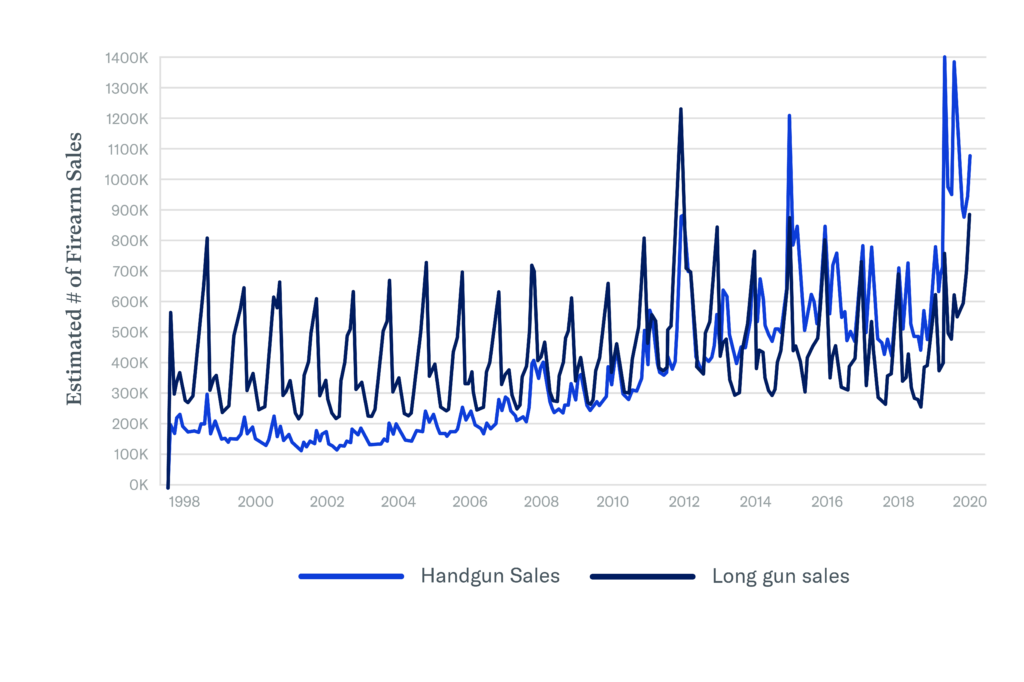

Surging Gun Sales

The US government declared a national emergency and states released social distancing guidelines in mid-March 2020. Almost immediately after, many Americans purchased guns; they felt they had to protect themselves, partially in response to gun lobby propaganda that social unrest was inevitable and that the government would not protect them.23Harry Eberts and Miranda Viscoli, “Gun Lobby, NRA Use Crisis to Boost Gun Sales,” Santa Fe New Mexican, April 13, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Tsl7hb; “Americans are flocking to gun stores because they know the only reliable self-defense during a crisis is the #2A. Carletta Whiting, who’s disabled & vulnerable to #coronavirus, asks Dems trying to exploit the pandemic: Why do you want to leave people like me defenseless?” NRA, “Twitter Post, 1:36 PM,” March 21, 2020, https://t.co/wDeEYHqzOU.

People responded to these messages. Throughout 2020, federally licensed gun dealers requested nearly 40 million background checks—40 percent more than during 2019. Based on these checks, Everytown estimates that people purchased 22 million guns in 2020, a 64 percent increase over 2019.24Everytown Research estimates using Federal Bureau of Investigation, NICS Firearm Checks: Month/Year by State and Type, https://bit.ly/2MllXs6; Jurgen Brauer, “Demand and Supply of Commercial Firearms in the United States,” Economics of Peace and Security Journal 8, no. 1 (April 22, 2013): https://doi.org/10.15355/epsj.8.1.23; Everytown estimated the number of firearms sold for each month and year using the methodology of the Small Arms Survey, an adaptation of the method used by Small Arms Analytics & Forecasting. They estimate that 1.1 firearms are sold for each handgun and long gun check, and 2 firearms are sold for each “multiple” check conducted. The state numbers are as provided by the FBI. The sum of these numbers does not equal the US FBI totals. Everytown excluded the US territories from this analysis. According to FBI data, nine out of the 10 weeks with the highest demand for National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) checks since the system became operational in 1998 occurred during 2020.25Federal Bureau of Investigation, NICS Firearm Checks: Top 10 Highest Days/Weeks, November 30, 1998–December 31, 2020, accessed January 6, 2021, https://bit.ly/31R98NV.

There were an estimated 22 million guns purchased in 2020, a 64% increase over 2019.

This surge in gun sales has continued into 2021. In January 2021, it is estimated that 2.1 million guns were sold.26Daniel Nass, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom,” The Trace, August 3, 2020, https://bit.ly/3e3aDiK. These sales contributed to January setting an all-time record for the highest number of NICS checks requested in a one-month period since the system’s creation. That record was broken again in March, with an estimated 5.9 million guns sold in the period from January to March 2021.27Federal Bureau of Investigation, NICS Firearm Checks: Month/Year, November 1998–March 31, 2021, accessed April 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3eldbXB.

The surge in guns purchased from federal dealers put a huge strain on the background check system. It also highlighted that this otherwise strong system is exposed to a series of loopholes and end runs that undermine our gun safety laws and gun violence prevention efforts. The NRA-backed28Jennifer Mascia, “How America Wound Up with a Gun Background Check System Built More for Speed Than Certainty,” The Trace, July 21, 2015, https://bit.ly/2Q0k9Kb. “Charleston loophole”29The loophole takes its name from the 2015 shooting of nine worshipers at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina, where the shooter, though legally prohibited from having a firearm, was able to buy the gun he used in the shooting because his background check was not completed within three business days. Michael S. Schmidt, “Background Check Flaw Let Dylann Roof Buy Gun, FBI Says,” New York Times, July 10, 2015, https://nyti.ms/2VmlD0y. and unlicensed seller loophole, as well as the ATF’s flawed interpretation of law that has allowed for the proliferation of ghosts guns, have made it far more likely that guns will fall into the wrong hands.

The surge in gun sales put a huge strain on the background check system.

These loopholes and end runs can be closed. Some states have already implemented laws to require background checks for gun sales by unlicensed sellers, to give authorities more than three business days to complete a background check, and to regulate the sale of ghost guns and the parts necessary to build them. Recently, Congress and the Biden-Harris Administration have started to take steps to address these issues. In March 2021, the House of Representatives passed the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2021, which would update federal law to require background checks on all gun sales30117th Congress (2021–2022), H.R. 8, the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/8. and passed the Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2021, to address the Charleston loophole.31117th Congress (2021–2022), H.R. 1446, the Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1446. In April 2021, the Biden administration announced it would be taking action to stop the spread of ghost guns.32Biden-Harris White House, “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Initial Actions to Address the Gun Violence Public Health Epidemic,” April 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/32VYp5b. Swift action by state legislatures and the US Senate can help change the tide of the spikes in gun violence we have seen across the country.

Unintentional Shootings by Children and the Risk of Youth Gun Suicide

One defining aspect of the COVID-19 crisis has been the closing of America’s schools. This kept children home across the country and, in too many cases, put them into direct contact with the millions of guns in American homes. In some households, these were first-time gun owners, who were often unable to access training due to the pandemic—leaving many of them without essential knowledge on how to securely store firearms.

Before the pandemic, on average nearly one child per day was accessing a gun and unintentionally shooting themselves or another person.33Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “#NotAnAccident Index,” 2020, https://everytownresearch.org/maps/notanaccident/. With children stuck at home, we clearly see the consequences of guns not being stored properly. The period from March to December 2020 saw a 31 percent increase over the same months in 2019 in unintentional shooting deaths by children. In total, there were 314 incidents of unintentional shootings by children between March and December of 2020, resulting in 128 gun deaths and 199 nonfatal gun injuries.34Everytown analysis using #NotAnAccident Index 2019–2020 data. Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “#NotAnAccident Index.” This includes toddlers, young children, and teenagers 17 and younger accessing a gun and unintentionally injuring or fatally wounding a sibling, a schoolmate, another family member or friend, or themselves.

While millions of responsible gun owners store their firearms securely—that is, unloaded and locked, with ammunition kept in a separate place—more than half of gun owners do not store all of their guns securely.35Cassandra K. Crifasi et al., “Storage Practices of US Gun Owners in 2016,” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 4 (2018): 532–37, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304262. Researchers estimate that roughly 4.6 million children in the United States live in a home with an unsecured firearm.36Matthew Miller and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Storage in US Households with Children: Findings from the 2021 National Firearm Survey,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (2022): e2148823, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48823. This has likely increased as gun sales have surged. A recent survey of teens in gun-owning households found that more than half reported they could access a loaded gun in their home in under an hour. And most said they could access the gun in under five minutes.37Carmel Salhi, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Parent and Adolescent Reports of Adolescent Access to Household Firearms in the United States,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 3 (March 9, 2021): e210989, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0989. This easy access to firearms by children increases the risk of unintentional shootings and suicides.

Unintentional Shooting Deaths by Children Went Up Over 30% in March to December of 2020 Compared to 201938Everytown analysis of #NotAnAccident Index.

| March–December 2019 | March–December 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Unintentional gun injuries (by a child 0–17) | 169 | 199 |

| Unintentional gun deaths (by a child 0–17) | 98 | 128 |

| Unintentional shootings (by a child 0–17) | 255 | 314 |

4.6M

4.6 million children in the US live in a home with at least one unlocked and loaded firearm.

The COVID-19 pandemic fractured the lives of young people in the United States. Being socially isolated from others as a precaution against COVID-19, though necessary, has been damaging to their mental health. Many young people, particularly teenagers, remain socially isolated at home or on campus, missing out on peer interactions and milestones they have been looking forward to for years.39Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “COVID-19 Parental Resources Kit,” COVID-19 and Your Health, December 28, 2020, https://bit.ly/3wABji1. One study found that precautions related to the pandemic cut in half the amount of time young adults spent socializing.40Osea Giuntella et al., “Lifestyle and Mental Health Disruptions during COVID-19,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 9 (March 2, 2021): e2016632118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2016632118.

Social isolation along with fear about the virus increased feelings of anxiety and loneliness.41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Coping with Stress,” Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), July 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/3l4gq9u. These two factors elevate the risk of suicide for people of all ages. A 2020 study from the CDC found that a quarter of young adults (ages 18–24) contemplated suicide since the beginning of the pandemic.42Mark É. Czeisler et al., “Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, no. 32 (August 14, 2020): 1049–57, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. The proportion of young people at risk for clinical depression nearly doubled in the early months of the pandemic compared to before the pandemic.43Giuntella et al., “Lifestyle and Mental Health.” This is particularly troubling since students have been away from school counselors and other mental health resources. Schools have proven to be an important place to receive mental health services for children and youth, especially for some Black students who may not have access to medical care in other settings.44Rachel N. Lipari et al., “Adolescent Mental Health Service Use and Reasons for Using Services in Specialty, Educational, and General Medical Settings” (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013), https://bit.ly/2PupuJw.

With 70 percent of unintentional shootings by children (of themselves or others)45Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “#NotAnAccident Index.” and 80 percent of child gun suicides46Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), Ages 0–17, Five-Year Average: 2013 to 2017. taking place at a home, practicing secure firearm storage can prevent access by children and save lives. One study in JAMA Pediatrics estimated that if half of households with children that contain at least one unlocked gun switched to locking all their guns, one-third of youth gun suicides and unintentional deaths could be prevented.47Michael C. Monuteaux et al., “Association of Increased Safe Household Firearm Storage with Firearm Suicide and Unintentional Death among US Youths,” JAMA Pediatrics 173, no. 7 (2019): 657–62, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078.

Across the country, medical professionals, gun dealers, law enforcement, community members, and local leaders are working to promote public awareness campaigns. Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America’s Be SMART program, for example, encourages secure gun storage practices. The initiative also highlights the role of guns in suicide and unintentional shootings. As more adults have brought guns into their homes during the pandemic, the need for secure firearm storage has become even more critical.

Impact on Gun Suicide

COVID-19 created a perfect storm of risk factors for suicide and the fear that we would add additional firearm suicides to what is already an epidemic at crisis proportions. These risk factors included financial distress, social isolation caused by lockdowns, anxiety about a new disease with many unknowns, increased alcohol use, and vulnerability of frontline workers to exposure to the disease. Further, as gun purchases surged, the risk of a worsened gun suicide crisis intensified.48Tara Nurin, “During Self-Isolation, More People Show Online Interest in Alcohol Than Healthcare,” Forbes, April 11, 2020, https://bit.ly/2VJgEb9; Carrie Henning-Smith, “COVID-19 Poses an Unequal Risk of Isolation and Loneliness,” The Hill, March 18, 2020, https://bit.ly/2yymDHa; Ashley Kirzinger et al., “KFF Health Tracking Poll—Early April 2020: The Impact of Coronavirus on Life in America,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2, 2020, https://bit.ly/3bH67D0; Panchal et al., “Implications of COVID-19”; Federal Bureau of Investigation, NICS Firearm Checks.

While we are not out of the woods yet, preliminary CDC data on overall suicides in 2020 shows the possibility that suicide may have gone down slightly compared to 2019.49Farida B. Ahmad and Robert N. Anderson, “The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020,” JAMA, March 31, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.5469. Final data on firearm suicide during the pandemic is still forthcoming. But this early promising news may be due, in part, to a set of concerted relief efforts that address economic, mental health, and other suicide risk factors: Congress enacted three stimulus packages;50Public Law No. 116-136; Public Law No. 116-260; Public Law No. 117-2. Unemployment benefits and public assistance programs (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) were expanded.National Conference of State Legislatures, “COVID-19: Unemployment Benefits,” July 16, 2020, https://bit.ly/3tfNUo6; Katie Shantz et al., “Changes in State TANF Policies in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic,” (Urban Institute, August 4, 2020), https://urbn.is/3ufvrcJ. Rent assistance and eviction moratoriums were implemented;51US Department of the Treasury, “Emergency Rental Assistance Program,” accessed May 3, 2021, https://bit.ly/3xH0YpX; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19,” April 13, 2021, https://bit.ly/2RjXwB5. Insurance companies increased coverage of mental health services;52“Health Insurance Providers Respond to Coronavirus (COVID-19).” America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), accessed May 3, 2021, https://bit.ly/3h0fZ0a. Health equity efforts were deployed;53Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC COVID-19 Response Health Equity Strategy: Accelerating Progress Towards Reducing COVID-19 Disparities and Achieving Health Equity,” August 21, 2020, https://bit.ly/3aZmz3d. And access to suicide prevention services were strengthened.54Danuta Wasserman et al., “Adaptation of Evidence‐Based Suicide Prevention Strategies During and After the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” World Psychiatry 19, no. 3 (2020): 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20801.

3x

Access to a gun triples the risk of death by suicide.

Anglemyer A., Horvath T., & Rutherford G. “The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. Annals of internal medicine, (2014). https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301

Notwithstanding this preliminary data on 2020, research on the impact of the pandemic on suicide risks shows that cause for concern persists. One survey of people who bought guns during the summer of 2020 found they were more likely to report thoughts of suicide than gun owners who did not buy them during the pandemic.55Michael D. Anestis et al., “Suicidal Ideation among Individuals Who Have Purchased Firearms during COVID-19,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 60, no. 3 (March 2021): 311–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.10.013. This finding is alarming since access to a firearm in the home triples the risk of death by suicide.56Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (January 21, 2014): 101–10, https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301. The firearm suicide risk is exponentially higher—100 times higher—immediately after buying a handgun.57David M. Studdert et al., “Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California,” New England Journal of Medicine 382, no. 23 (June 4, 2020): 2220–29, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1916744. Tracking of mental health throughout the pandemic showed that approximately two in five US adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression. This is a rate four times higher than pre-pandemic levels.58Nirmita Panchal et al., “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 10, 2021, https://bit.ly/3cFnffp. It is not surprising, then, that the volume of calls and texts to crisis helplines spiked in March 2020 and stayed high throughout the year.59Amanda Jackson, “A Crisis Mental-Health Hotline Has Seen an 891% Spike in Calls,” CNN, April 10, 2020, https://cnn.it/3dkTcHc; Bethany Ao, “Calls Keep Soaring at Philly and National Crisis Hotlines: ‘It Spiked and Hasn’t Stopped,’” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 26, 2020, https://bit.ly/3wgLeJv.

Focusing in particular on the economic impacts of the pandemic, historical research indicates that access to a gun and economic stress significantly increase the risk of adult suicide.60Anglemyer, Horvath, and Rutherford, “Accessibility of Firearms and Risk”; Aaron Reeves et al., “Increase in State Suicide Rates in the USA during Economic Recession,” The Lancet 380, no. 9856 (2012): 1813–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61910-2; Feijun Luo et al., “Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928–2007,” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. 6 (2011): 1139–46, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300010; Camilla Haw et al., “Economic Recession and Suicidal Behaviour: Possible Mechanisms and Ameliorating Factors,” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 61, no. 1 (2015): 73–81, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014536545. In March and April 2020, unemployment in the United States approached levels not seen since the Great Depression. Nearly a year later, 9.7 million people were still unemployed in March 2021. Job loss, particularly when sustained, can result in eviction, foreclosure, and increased debt. These extreme economic stressors contribute to a sense of hopelessness, depression, and strained relationships. All of these can lead to suicidal behaviors.61Haw et al., “Economic Recession and Suicidal Behaviour.”

Access to a gun and economic stress significantly increase the risk of adult suicide.

An important tool to prevent gun suicide is Extreme Risk laws. They empower loved ones and/or law enforcement to intervene to prevent someone in crisis from accessing firearms. These laws, enacted in 19 states and DC,62CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, HI, IL, IN, MA, MD, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, RI, VA, VT, and WA. have continued to be lifesaving tools during the COVID-19 pandemic. States and court systems have protected public safety by adapting to the challenges created by the pandemic, taking measures to ensure that Extreme Risk interventions can continue even with social distancing restrictions in place.

Impact on Domestic Violence

Prevention measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 had an immediate and grave impact on domestic violence. In the early days of the pandemic, countries around the world were reporting increases in domestic abuse.63Edith M. Lederer, “UN Chief Urges End to Domestic Violence, Citing Global Surge,” NBC 4 New York, April 5, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Tsd6Zh. Victims and their children were trapped at home with abusive partners and the financial stressors of the dramatic economic downturn and the social isolation of lockdown orders worsened this abuse. Ready access to guns can make this problem more deadly.64Jacquelyn C. Campbell et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results from a Multisite Case Control Study,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 7 (July 2003): 1089–97, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1089.

5x

Access to a gun makes it five times more likely that an abusive partner will kill his female victim.

Campbell, J. C. et al. “Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study”. American Journal of Public Health. (2003). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089

Fast forward to later in 2020, and while hard data is not yet fully available, a survey conducted in the final quarter of 2020 of domestic violence service providers in over 40 states shed some light on domestic violence and guns. A significant proportion of respondents identified guns as a larger threat in intimate partner violence during the pandemic and about half were seeing an increase in gun threats toward survivors of intimate partner violence in their communities.65Kellie Lynch and T. K. Logan, “Assessing Challenges, Needs, and Innovations of Gender-Based Violence Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results Summary Report” (San Antonio: University of Texas at San Antonio, February 2021), https://bit.ly/2OZRx32. Additionally, a study of 14 large US cities found that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with an eight percent increase in domestic violence calls to police in the initial three months of the pandemic. Households without a recent history of domestic violence calls drove much of this increase.66Leslie and Wilson, “Sheltering in Place and Domestic Violence.”

Research shows that access to a gun makes it five times more likely that a woman will die at the hands of a domestic abuser.67Campbell et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide.” The COVID-19 crisis worsened the factors that contribute to our current gun-related domestic violence crisis. Gun ownership surged and personal finances were strained. Quarantine requirements and school closures meant victims and children had fewer opportunities to interact with friends, teachers, co-workers, and others who might see signs of abuse or help to report them. Nationwide social distancing measures have ravaged sectors (such as retail and hospitality) where female workers constitute a significant portion of the workforce.68Rafael Nam, “Women Suffering Steeper Job Losses in COVID-19 Economy,” The Hill, May 25, 2020, https://bit.ly/31CCajY; Titan Alon et al., “This Time It’s Different: The Role of Women’s Employment in a Pandemic Recession” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2020), https://doi.org/10.3386/w27660; Maria Aspan and Emma Hinchcliffe, “5 Steps the US Government Could Take to Tackle the Crisis Facing Working Women,” Fortune, February 1, 2021, https://bit.ly/31Ccjcf. The culmination of all of these factors has made women especially vulnerable during this time.

13%

States that prohibit domestic abusers from possessing guns have seen a 13 percent reduction in intimate partner firearm homicide rates.

Zeoli, A. and et al. “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Associations With Intimate Partner Homicide”. American Journal of Epidemiology. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx362 (Retraction published Am J Epidemiol. 2018 Nov 1;187(11):2491)

Domestic violence and the compounding effects of the pandemic highlight the importance of strengthening and enforcing laws to keep guns out of the hands of abusive partners and of providing support to domestic violence shelters, hotlines, and courts. States can help keep guns from domestic abusers not only by prohibiting abusive spouses from having guns, but also by prohibiting abusive dating partners from having them69Federal law prohibits domestic abusers from having guns, but only if they have been married to, have lived with, or have a child with the victim. It does not otherwise prohibit abusive dating partners from having guns. This gap in the law is known as the “boyfriend loophole” and has become increasingly deadly. The share of homicides committed by dating partners has been increasing for three decades, and now women are as likely to be killed by dating partners as by spouses. and by requiring abusers to relinquish the guns they already own. Currently, 26 states and DC prohibit abusive dating partners from having guns,70CA, CT, DC, DE, HI, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, ME, MN, NC, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OR, PA, RI, TX, VT, WA, WI, and WV. These states prohibit dating partners under final domestic violence restraining orders and/or dating partners convicted of misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence from having guns. and 23 states and DC require prohibited domestic abusers to relinquish their guns.71CA, CO, CT, DC, HI, IA, IL, LA, MA, MD, MN, NC, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, PA, RI, TN, VA, WA, and WI. These states require abusers under final domestic violence restraining orders and/or abusers convicted of misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence to turn in their firearms when they become prohibited from having them. Research shows that states that have these prohibitions from possessing guns for both spouses and dating partners have seen a 13 percent reduction in intimate partner firearm homicide rates. Those that also require abusers to turn in guns they already own have a 16 percent lower intimate partner firearm homicide rate.72April M. Zeoli et al., “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Associations with Intimate Partner Homicide,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187, no. 11 (November 2018): 2365–71, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy174.

Increases in Anti-Asian Hate Crimes

In March 2021, a gunman took eight lives—six of whom were Asian women—in an act of hate-related violence at spas in metro Atlanta.73Henri Hollis, Shaddi Abusaid, and Alexis Stevens, “‘A Crime against Us All’: Atlanta Mayor Condemns Deadly Spa Shooting Spree,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 17, 2021, https://bit.ly/2PKJhER. This was a continuation of violence against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community that exploded throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Stop AAPI Hate, an organization tracking incidents of hate and discrimination against the AAPI community, received nearly 3,800 reports of anti-Asian hate incidents from March 2020 to February 2021.74Russell Jeung et al., “Stop AAPI Hate National Report, 3/19/20–2/28/21,” Stop AAPI Hate, March 16, 2021, https://bit.ly/3rDkkbr. This is an average of roughly 10 incidents every day. Police departments in the 16 largest US cities reported a nearly 150 percent increase in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans in 2020.75Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, “Anti‐Asian Prejudice March 2020,” March 1, 2021, https://bit.ly/3cJcU1O. AAPI women have been particularly targeted during the pandemic. Nationally, Asian American women were more than twice as likely to be targeted in hate incidents as Asian American men.76Jeung et al., “Stop AAPI Hate Report.” But violence against women, fueled by misogyny, racism, and fetishization, has plagued the United States for generations. Easy access to guns makes all hate-motivated violence, including that against AAPI women, even deadlier.

Easy access to guns makes all hate-related violence, including that against AAPI women, even deadlier.

We must invest in protecting marginalized communities, especially during this critical time. The root causes of hate-fueled violence will take a long time to address. But strengthening our gun laws by reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act77Everytown for Gun Safety, “Reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act,” March 9, 2021, https://www.everytown.org/report/reauthorize-the-violence-against-women-act/. can go a long way toward protecting women right now.

The Path Forward

Over the last year, the United States has seen the collision of two major public health crises: COVID-19 and gun violence. A full understanding of this collision’s impact on our country is still developing. But a few things are clear. Millions of Americans bought guns in the middle of a global pandemic. They bought these guns to protect themselves in the midst of one public health crisis but exposed themselves to the risks of another: gun violence. With more guns came exposure to higher risks of suicide, and more homicides and unintentional shootings.78Anglemyer, Horvath, and Rutherford, “Accessibility of Firearms and Risk”; Campbell et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide”; Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “#NotAnAccident Index.”

At the same time, the pandemic exacerbated economic and social inequities fueling gun violence. These inequities subject marginalized communities to structural and interpersonal violence that is damaging and can be deadly. The pandemic has become a sobering wake-up call to this country. It alerts us to existing issues that put all Americans, especially those in vulnerable communities, in harm’s way.

The increase in gun deaths during this pandemic has shined a light on our nation’s shortcomings. But it has also illuminated the path forward. Our work must include implementing proven policies that protect ourselves and others. We must strengthen our background check system and promote secure gun storage. It is imperative that we fund community-based violence intervention and suicide prevention programs. And that we adopt and implement Extreme Risk laws and policies separating domestic abusers from their guns, both of which are proven to save lives.

We need to advance the essential work of rectifying the ills of economic, social, and structural inequity. This means ensuring access to fundamental services such as health care and domestic violence and mental health services. The benefits of instituting evidence-informed policies are manifold. In doing so, we invest in the cost-effective strategy of prevention, improve the plight of Americans across the country, and ultimately save lives.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.