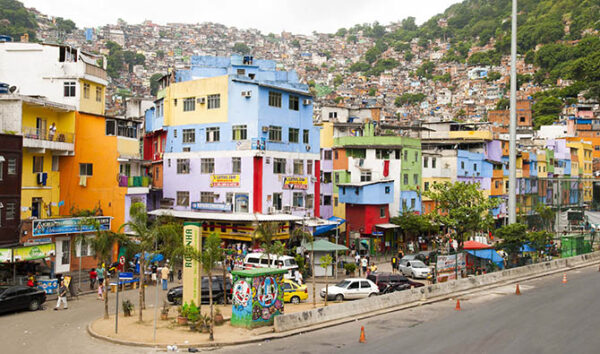

A study co-led by Vanderbilt University’s Dominique Béhague found that Brazilian citizens without traditional public health expertise have stepped up and worked together in poor neighborhoods known as favelas to make significant strides in their community’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Béhague, associate professor of medicine, health, and society, and Francisco Ortega, research professor at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Barcelona, Spain, co-authored a recent article in The Lancet about their findings.

They contend that collective social medicine—built on mutual aid and solidarity practices among neighborhood groups and local journalists—challenges conventional assumptions about the efficacy of hierarchical leadership models, disease-specific programs and other common practices in public health.

“Government and institutional investment in public health is vital, but we have also seen a growing number of distinct initiatives and funding streams, which can lead to duplication of efforts, lack of coordination and unnecessary hyperspecialization,” said Béhague, who is also affiliated with King’s College, London. “Favela community organizers are showing us that effective public health action can take shape at a local level in a synergistic and multi-pronged way. This begs the question of why the public health community has not been more effective at the national and global levels with all the resources they bring to bear.”

“Favela community organizers are showing us that effective public health action can take shape at a local level in a synergistic and multi-pronged way. This begs the question of why the public health community has not been more effective at the national and global levels with all the resources they bring to bear.”

The researchers observed that the community activists’ work in the favelas target COVID-specific issues while also tackling overarching societal factors of unemployment, mental health and food security. Their work is decentralized and shared collectively among local groups and individuals, including journalists who assist with the food distribution while continuing to report and counter misinformation about COVID-19.

Favela activists have created their own data collection systems to get an accurate view of the local COVID-19 situation and respond rapidly, from monitoring and distributing donations to managing volunteers and countering disinformation.

“The community activists’ alliances, which reject traditional hierarchies and commit to working through political differences, are fighting COVID-19 in a much more equitable manner,” Behague said. “These unorthodox approaches demonstrate that social medicine is a model for reimagining public health—not just in the favelas of Brazil but also around the world.”

The publication is part of a special series, “Revitalising global social medicine,” edited by Michelle Pentecost, Vincanne Adams, Rama Baru, Carlo Caduff, Jeremy A Greene, Helena Hansen, David S Jones, Junko Kitanaka and Francisco Ortega.