Shortly after the turn of century, America’s largest virtual retailer, famously founded to sell one product, made an extraordinary shift. After years of only mailing goods to home shoppers, it started operating dozens of physical stores throughout the country. A model of operational efficiency, the company was light-years ahead of its peers in both technology and strategy, with a devotion to low prices, unrivaled choice, and customer service. It grew to become a microcosm of the U.S. economy, spanning not only retail but also warehousing and marketing.

Is the above paragraph about Sears in the 20th century or Amazon in the 21st century? As I wrote last week, it’s both. Sears’s playbook both explains and predicts the awe-inspiring (and, occasionally, confusion-inspiring) strategy of Jeff Bezos and his Seattle juggernaut. But as much as Amazon’s leaders can learn about their own company by studying Sears’s incredible rise, they can learn even more by studying Sears’s steep decline.

Sears faced two identity crises in the 20th century, according to the wonderful essay “Sears, Roebuck in the Twentieth Century,” by Daniel M. G. Raff, an associate professor of management at Wharton, and Peter Temin, the former head of MIT’s economics department. In the early 1900s, Sears was famous for its capacious catalogue and mail-order delivery business. But a recession following World War I hurt farmers on whose income Sears had come to depend. Meanwhile, the rise of urban chain stores threatened to reshape the national retail industry. Sears was saved by Robert Wood, a retired military general who studied the U.S. Census and Statistical Abstract of the United States as if they were Talmudic literature. It was Wood who pushed Sears to expand in the South and West, where Americans were moving, and Wood who urged it to become a brick-and-mortar company. In January of 1925, Sears had no physical stores in the United States. By the end of 1929, it had 300.

This shift set up Sears for a long run as one of America’s most successful companies. The firm served as America’s top hardware outlet and service provider, which sold Americans both car parts and car insurance. In the middle of the 20th century, Sears’s domestic annual revenue hovered around 1 percent of U.S. GDP, or the equivalent of about $180 billion in today’s dollars. (In 2016, Amazon’s still-impressive North American revenue was “only” $80 billion.)

But Sears faced another existential crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, and that time, it failed to adjust. The decline of manufacturing (and manufacturing jobs) hit both its most devoted consumers and the value of its real estate near steel towns. The blue-collar families Sears counted on to buy “utilitarian Sears pants and dresses … were a fading force in the marketplace,” Raff and Temin write. What’s more, other stores had chased Sears into America’s middle-class suburbs—sometimes, they even snuggled up to Sears locations in the same strip malls—erasing the company’s geographical edge.

This second existential crisis called for a second strategy shift. But, lacking the vision of General Wood, Sears’s leadership made several grave errors that doomed the company.

First, Sears determined that it didn’t need to do anything to change its business. It simply needed more businesses. After all, its leaders must have thought, if a company that started selling only watches could get into car parts, and a hardware company could get into insurance, why couldn’t a watch-and-cars-and-hardware-and-insurance company get into, well, anything? Since it was the 1980s, anything, in this calculation, meant “financial services.” As the company’s head of strategy said in 1980, “There is no reason why someone shouldn’t go into a Sears store and buy a shirt and coat, and then maybe some stock.”

Eager to become America’s largest brokerage, and perhaps even America’s largest community bank, Sears bought the real-estate company Coldwell Banker and the brokerage firm Dean Witter. It was a weird marriage. As the financial companies thrived nationally, their Sears locations suffered from the start. Buying car parts and then insuring them against future damage makes sense. But buying a four-speed washer-dryer and then celebrating with an in-store purchase of some junk bonds? No, that did not make sense.

But the problem with the Coldwell Banker and Dean Winter acquisitions wasn’t that they flopped. It was that their off-site locations didn’t flop—instead, their moderate success disguised the deterioration of Sears’s core business at a time when several competitors were starting to gain footholds in the market.

Many decades after Sears had left Montgomery Ward, its old competitor, in the rural dust, another retailer was budding in small-town America. Its name was Walmart. Located on cheaper rural land than Sears, often paying cheap wages, and selling cheaper goods for cheaper prices, Walmart’s innovation seemed to be, well, a talent for cheapness. But its secret weapon was information technology. Walmart managed its supply chain with extraordinary precision. Its distribution centers were ingeniously located in central locations to optimize for efficient delivery to its stores.

Most importantly, Walmart used cutting-edge technology to manage its shelf space. It knew which items were selling fastest, at which prices, and in which cities. This data went not only to individual store managers but also to Walmart headquarters, so that the company could place huge orders for the best-selling brands and products. Rather than rely on the decision-making of individual buyers or store managers, Walmart’s data-driven approach allowed corporate leaders to oversee their stores’ performance, down to the minute level of what was popular on each shelf. Walmart’s obsessive focus on low prices was aided by an obsession with understanding exactly what products to order—and no more.

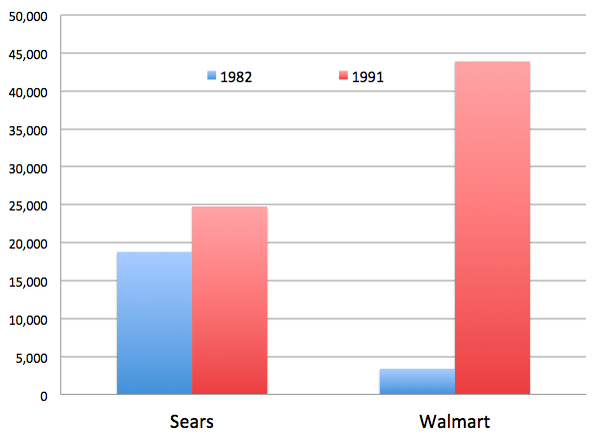

While Sears was expanding into stocks and mortgages, it failed to develop sophisticated ways of telling which types of merchandise, or which stores, were performing the best. Instead, they relied on store managers to be ambassadors, reporting local trends back to the mothership. Sears’s revenue was five times larger than Walmart’s in the early 1980s. By the early 1990s, it was bringing in scarcely half what Walmart was.

Total Annual Revenue by Retailer, in Millions of Dollars

There are four broad lessons that Amazon can glean from the story of Sears’s decline.

First, retail is in a state of perpetual metamorphosis. In the last 150 years, the locus of American shopping has moved from small supply stores, to mail-ordering, to department stores, to chain stores, to big-box superstores, back to mail-to-consumer shopping, and then, perhaps, onto some combination of pop-up retailers and national online behemoths. People are constantly seeking more convenient ways of buying stuff, and they are surprisingly willing to embrace new modes of shopping. As a result, companies can’t rely on a strong Lindy Effect in retail, where past success predicts future earnings. They have to be in a state of constant learning.

Second, even large technological advantages for retailers are fleeting. Sears was the logistics king of the middle of the 20th century. But by the 1980s and 1990s, it was woefully behind the IT systems that made Walmart cheaper and more efficient. Today, Amazon now finds itself in a race with Walmart and smaller online-first retailers. Jeff Bezos has invested in all sorts of emerging technology, many of which might lead to dead ends. But it’s important for Amazon to stay aggressive about experimenting with new platforms, in case one of today’s underdeveloped technologies—like ordering through AI assistants, delivery-by-drone, or virtual and augmented reality—turns out to be the next big thing that transforms retail, all over again. On this front, Amazon shows few signs of technological complacency, but the company is still only in its early 20s; Sears was overtaken after it had been around for about a century.

Third, there is no strategic replacement for being obsessed with people and their behavior. “Information technology was to the 1980s as the automobile was to the 1920s,” Raff and Temin write. “It provided a new way for consumers to interact with retailers.” Walmart didn’t overtake Sears merely because its technology was more sophisticated; it beat Sears because its technology allowed the company to respond more quickly to shifting consumer demands, even at a store-by-store level. When General Robert Wood made the determination to add brick-and-mortar stores to Sears’s mail-order business, his decision wasn’t driven by the pursuit of grandeur, but rather by an obsession with statistics that showed Americans migrating into cities and suburbs inside the next big shopping technology—cars. Amazon will benefit from a similar fixation on consumer behavior: where they live, how they spend time, and through what devices they’re starting to shop. On this count, too, Amazon appears to be extremely well positioned; it is renowned for scrupulously anticipating consumers’ every desire.

Finally, adding more businesses is not the same as building a better business. When Sears added general merchandise to watches, it thrived. When it added cars and even mobile homes to its famous catalogue, it thrived. When it sold auto insurance along with its car parts, it thrived. But then it chased after the 1980s Wall Street boom by absorbing real-estate and brokerage firms. These acquisitions weren’t flops. Far worse, they were ostensibly successful mergers that took management’s eye off the bigger issue: Walmart was crushing Sears in its core business. Amazon should be wary of letting its expansive ambitions distract from its core mission—to serve busy shoppers with unrivaled choice, price, and delivery speed.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.