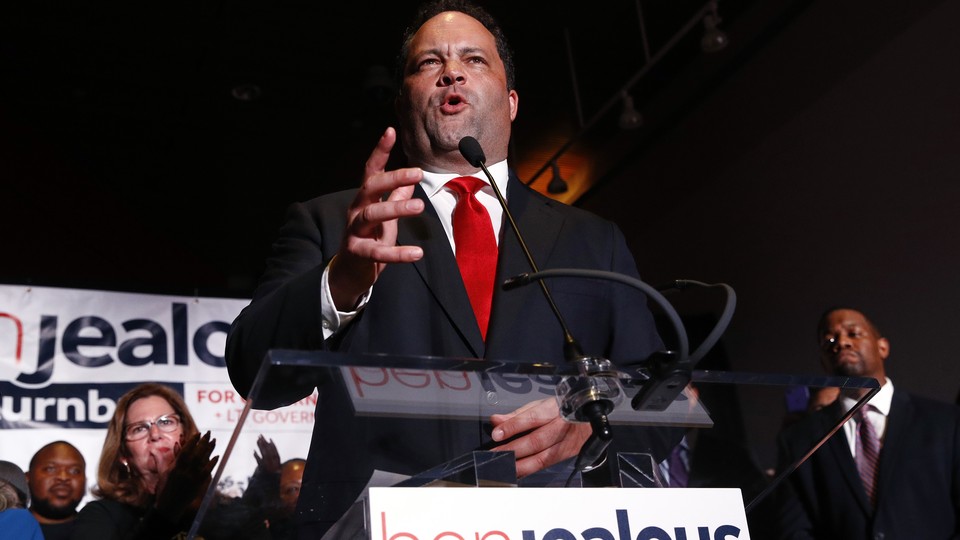

What Ben Jealous’s Win Means for Democrats

The former NAACP chief won Maryland’s Democratic primary on Tuesday by campaigning as an enthusiastic progressive. But he faces the very popular Republican incumbent Larry Hogan in November.

Ben Jealous has a theory of the 2018 Maryland gubernatorial election: that an enthusiastically progressive candidate can defeat the state’s popular Republican governor, Larry Hogan. After his victory in Tuesday night’s Democratic primary, Jealous will get to put that theory to the test.

“If someone voted for Hogan last time, I’m not trying to convince them to do different this time. If somebody didn’t vote last time, I’m focused on them and getting them to turn out,” Jealous told me in an interview in early June. “And we will have much higher voter turnout, and he will lose. It’s just that simple.”

Jealous pulled out a stronger-than-expected victory on Tuesday, on a night in which progressive candidates in several states edged out more conservative or establishment challengers. In a field with nine contenders, Jealous, a former NAACP chief who has never held elected office, won 40 percent of the vote. He defeated his closest opponent, Prince George’s County Executive Rushern Baker, by 10 points, suggesting a level of enthusiasm that wasn’t picked up in public polls ahead of the election.

“Looks like he picked up a ton of the undecided vote—remember polls had 30-plus percent undecided two weeks ago,” said Mileah Kromer, the director of the Sarah T. Hughes Field Politics Center at Goucher College in Maryland. “Not surprising, if you look at the money he received from outside sources and the big names who came and stumped for him in the Dem strongholds. He had the resources and campaign organization to put it away in the waning days.”

As I reported earlier this week, Jealous ran to Baker’s left on policy, campaigning on single-payer health insurance, free in-state tuition, marijuana legalization, raising taxes on the wealthy, and shrinking the prison system. He won the backing of unions, like Maryland’s teacher’s union and the Service Employees International Union, and benefited from big donations from out of state. He also had the backing of a number of national figures, including Senators Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, and Kamala Harris. Jealous’s policy agenda would turn the state into an experiment in progressive governance, testing many of the ideas popularized during Sanders’s presidential primary run in 2016 in a single state.

“I am not running to the left. I am not running to the right. I am running towards the people of our state. Health care, education, ending mass incarceration, ending the student-debt crisis, and protecting the environment are people issues,” Jealous told supporters on Tuesday night. “And unlike Larry Hogan, I have the vision, the plans, the experience, and the courage to risk my own political standing for progress.”

But before he can do anything, Jealous has to beat Hogan, and that’s going to be a lift. A moderate who has worked with Democrats on many issues—while opposing them on others—Hogan has a 70 percent approval rating in Maryland, in which there are twice as many registered Democrats as Republicans.

“The question is whether a Sanders-style progressive can break apart the Hogan coalition of moderate Democrats, Independents, and Republicans,” Kromer said. “Turning out new or, as Jealous says, ‘unlikely’ voters is hard.”

At the same time, Hogan may be more vulnerable than he looks. Maryland’s 2014 gubernatorial election saw the lowest Democratic turnout since Reconstruction, according to John T. Willis, a former Maryland secretary of state and a professor at the University of Baltimore. Hogan’s margin of victory that year over Democrat Anthony Brown was a mere 66,000 votes.

Jealous’s backers believe that their candidate’s progressive policy agenda and organizing background will solve the enthusiasm problem that plagued Democrats in 2014. They’ll have help—President Trump is deeply unpopular in the state, and the opposition party is always spoiling for a fight in the midterms.

In the aftermath of the Democrats’ 2016 election defeat, many political analysts argued that the party would have to pick between a populist economic agenda or one focused on civil rights and social justice. Jealous’s victory, along with others on Tuesday, suggests that, in liberal strongholds at least, Democratic voters are comfortable pursuing both at once.