Books & Culture

My Summer of Slam: Poetry, Tom Waits, and What Stays With You

“Slam is confrontational, from reader to listener and vice versa.”

I owned an expensive suit that summer — the gift of a hopeful father — and I had a few practiced skills. I could open a matchbook and light one of the matches using only one hand, and without detaching the match in question from the pack (what you do is bend it around back with your thumb — note that you can burn your thumb this way). I could also recite big swaths of Shakespeare and improvise convincingly when I missed a line or flubbed it. That brace of talents, along with how to mix a proper stinger (two parts brandy, one part crème-de-menthe, highball glass, rocks) were about all I knew of the bigger world. I certainly knew almost nothing about the world that came to life at first light and hummed till 5 pm.

I was mistaken for a bike messenger at my first corporate interview (“Who sent you?”) and turned away with instructions to get a haircut and lose the earrings before I rescheduled. When I did land a job — in the mail room of a sleepy monolith — I found the sorting so numbing I often took a puff of marijuana at lunch and spent the next hour casing nooks where I might curl up to sleep. One afternoon it came to light that an exceptionally thin woman who worked alongside me had shined for a year as a tap dancer in New York.

I was mistaken for a bike messenger at my first corporate interview (“Who sent you?”) and turned away with instructions to get a haircut and lose the earrings before I rescheduled.

“You were a dancer in New York?” asked our boss, a shifty man who carried no bag or briefcase (“I like to travel light”).

“Oh sure, I was in shows. I danced off-Broadway.”

The copier washed us green.

“Why’d you quit? You’re still young enough.”

“Well,” her mien was blasé. “I just gave up and faced reality and got a real job. Like John did, right John?”

: : :

The basement of the Cantab Lounge in Boston was hosting the 1999 National Poetry Slam finals and it was lousy with audience. Some of the seats were filled with kids and some with ghosts who were still alive. A sly old devil with a handshake that could castrate bulls took my three dollars at the door and welcomed me as though I were a prodigal son. It was my first time there and I’d never recited a poem of my own in public. When I stood up to read the folded pages I’d brought along — some piece of surrealist nonsense with “a basket of rain” inside it — somehow the crowd stayed with me. When they clapped at the end the host said they’d like to see me back the next week. “And bring a basket of rain!” It was the doorman with the ordnance-grip. I’d found an audience.

It was my first time there and I’d never recited a poem of my own in public.

College had ended that spring, and until that night I hadn’t known there was a club around the corner. A friend from class had invited me out dancing and I’d taken philanthropic drugs and made some friends. 6’4’’, black leather and slicked hair, right side of my face obscured by a maze drawn with eye-liner in the dark, I was getting on well. I’d been kissed by a few strangers and the night was young.

I wasn’t a gifted dancer. A friend on the floor with me said, “No, not like that. Try to imagine you’re making love.” Seconds later: “Oh wait, no, don’t do that.” Later, by the bar, it came out that I’d been writing some poems, inspired then by my former teacher Bill Knott. “You’ve got to go to the Cantab,” my class friend said. “It’s practically next door. Let’s go now and come back in an hour.”

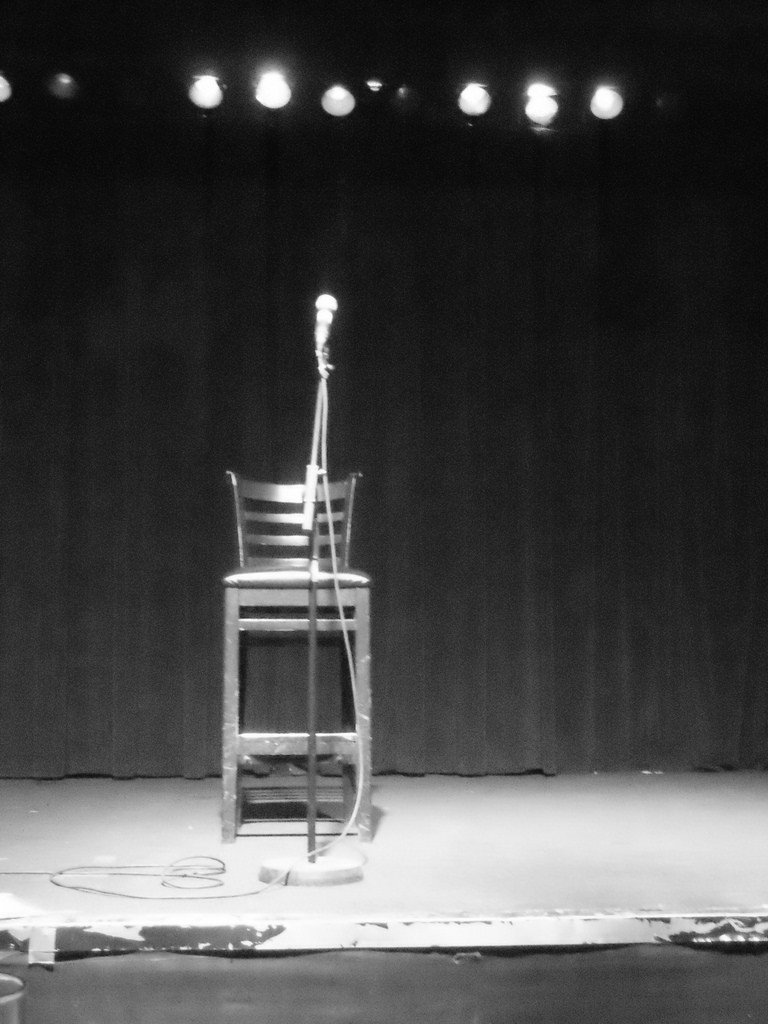

So we wandered down the steps of a dive bar filled with Cambridge locals (people who actually worked, as distinct from Harvard types) and into a room where I’d come to spend two years’ worth of Wednesday nights. Folding chairs and small Formica tables would always wait around a slightly raised black stage with a single microphone. The sign-up list would always fill up fast. Judy at the bar would always pour the well drinks strong.

That night, a woman my age — I’ll call her Vanessa — sat at a corner table with what I remember as two separate binders full of poems. They were her own poems and she and I started to flip through them and read them to each other, oblivious of the competition from the stage.

There are times when you feel attracted to a stranger simply because they’re attracted to you. That was Vanessa and me, both of us. We looked good together and people were good enough to note it. They’d tell us to get a room. But if they got a room, we decided, they wouldn’t have to watch us. Later that summer we’d go night swimming at Walden Pond, dance close at clubs, and talk about the real world not at all.

I’d only just met her — she’d just moved back to Boston from Cornell — but Vanessa made me proud when she reached the microphone that night. She looked at her notes and led us through our breathing by breathing herself, slowly. She backed away from the mic. The room settled back. She had that marvelous capacity to wave the room away and lure us into a kind of trance. How much of this was a put-on? And, in the context of performance poetry, does that question mean anything?

“Hush,” she said. The title? It seemed to be a known poem among the construction-job kids in the back rows and big-heeled barflies — they hooted. There were nods and hums. “Alright.” “Mmm.” Like some slam poets can do, she assumed authority by setting her shoulders, conjured the atmosphere of a Sunday service. We waited in attendance.

we children watch …

waiting for the marked to hum

for lips to leak and for the evening

to shadow to hover …

It wasn’t a revolutionary story and it was far from being, I’d later learn, Vanessa’s strongest work, but the manner in which she told it — the pauses, the casual leap that drops itself into sacerdotal water — allowed her to make something marvelous of it. The poem wasn’t something from the page but something from the air, a song, almost:

We knew the white folks and their kitchens

and bathrooms and broom-closets and their money.

We knew how to hold onto one another

“Hush,” she said again, and she held the hush. Slam poetry, then thoroughly derided in academic circles, is about as close as our culture comes to the kind of pre-literate half-chant of epics that Homer’s listeners would have known, or that Parry and Lord found in the Serbo-Croatian Folk Songs of the 1930s. Done well, it can have the same effect — like the best music, it makes us complicit in its progress; like the best stories, it moves quick and bright.

“And we hush.”

Applause.

: : :

“Hush your wild violet,” begins Tom Waits’ 1985 song “Hang Down Your Head.” Then: “Hush a band of gold.” I heard it nearly every day that year, and each time the story came fast: a gorgeous courtship, a marriage, but hush. He rumbles on: “Hush you’re in a story / That I heard somebody told.”

Has she been unfaithful? She has. “Tear the promise from my heart,” he whispers. There’s someone new in her life. He has to go and he’s broken about it. “Hush my love a train now …”

It’s standard ballad stuff, and you figure a ballad would be what he made of it, but he doesn’t. Instead he turns it into something that sounds like a pop song, maybe the Beatles. There’s syncopated drums, like Ringo’s in “Drive My Car.” The beat advances with a kind of lopsided rhythm. The baseline is tart and upbeat; the guitar is warm.

But because Waits is Waits, the parts don’t mesh, and therein lies the allure. A pump organ blankets the back with chords and harmonies, but from time to time it strays off-key. The lyrics resemble a Beatles song not at all. This is a song about shame: “Hang down your head for sorrow / Hang down your head for me.” The singer’s ashamed himself and yearns for the person who betrayed him to feel it too.

If anything, I dismissed the song completely when I first heard it on Rain Dogs, Waits’ masterpiece of 1985, because there was so much else there too. “Jockey Full of Bourbon” is the rocker, “Downtown Train” is the hit, and “Time” is the weeper (if you could watch Tori Amos sing the latter on Letterman right after September 11th and not choke up, then you were in a better place than the room full of people who saw it with me).

No, the first time I heard it, “Hang Down Your Head” head felt purely functional — something to transition the listener from what Waits calls a brawler to what he calls a bawler. In that capacity, it does its job, easing us into something more reflective while maintaining the drums and the electric guitar we’ve grown used to. But I didn’t see what else it did.

: : :

At the gig that succeeded my time in the mail room, I drummed out ad copy for Compaq’s high-end servers. It was regular work and I swallowed Vicodin and downloaded music from Napster to make the time pass. This until Carly Fiorina bought the company and disbanded it. Until then, for about two years, I made good money compiling booster pieces lauding the ProLiant DL380 and I did so to the sound of Rain Dogs, composing poems in my head that would sound good out loud.

And I read those poems out loud every Wednesday night. I was cocky at the Cantab, more so than I’d been before or have been since. I made friends at a heady clip. The kinds of verse they recited weren’t like the kind of verse I’d read on the page, and I liked that about them. Today, a settled snob, if I encountered that kind of poem-making, I’d call it bad poetry. But this is unhappy snobbishness and I didn’t hold it then.

Today, a settled snob, if I encountered that kind of poem-making, I’d call it bad poetry. But this is unhappy snobbishness and I didn’t hold it then.

Relying not on scansion or lexical delicacy but on the musicality of their delivery, the readers at the Cantab hummed and barreled their poems. I mentioned a church service above and I did so for a reason: slams and open mics and (some) featured guests at the Cantab felt more like such a ritual than anything I’ve experienced at a reading since — much more.

One night that February I sat between Vanessa and a woman I’ll call Ellen, a theater teacher from New York I’d dragged along. Ellen was skeptical, a mood that only deepened when it was revealed that the featured reader that night would be a towering and muscular poet named Zeus.

“Huh?” Ellen quietly scoffed. “Imagine if I started calling myself Zeus at school. Oh, here’s your professor this semester, Zeus.”

When Zeus himself appeared and it became apparent he was black (which Ellen and I are not) she waited until Vanessa had stepped out to smoke then added, “Does he realize ‘Zeus’ was the kind of thing slave masters used to call their property? It’s like what you’d name a mastiff. I just feel like … I don’t know his issues so maybe he knows and doesn’t care.”

Ellen was later described by a Wall Street friend we had in common as “a very unhappy young woman.” Probably because she rejected him. But there was something to it. She would change her identity periodically — her name, affect, milieu. There’s a book to be made about Ellen but she needs to write it. Suffice it to say I knew her in the drug-addled haze between her difficult girlhood in Appalachia and her suburbanite 40s as a mom. I loved her a little, and she loaned me good books. And we both loved Tom Waits more than we loved anything.

I loved her a little, and she loaned me good books. And we both loved Tom Waits more than we loved anything.

I don’t recall what Zeus read that night, probably the same sorts of pain and suffering every poet writes about. But his performance — his convincing, possibly authentic performance of sincerity — made Ellen bashful enough to quiet her. When Vanessa said, “That Zeus reading … I can still feel my skin tingling,” Ellen offered no retort. We made our way to my apartment in silence. Before that night I’d only seen Ellen that quiet when she was angry. But she wasn’t angry. I doubt she knew how she felt. That was me too.

: : :

On the uptown C to 81st Ellen and I sniggered over the college kid with the big grin at the end of our car. He was dressed in pointy buckled shoes with silver toes, a secondhand suit in carefully rumpled brown, and a porkpie hat. So of course we knew where he was going.

“It’s not a Tom Waits concert,” Ellen said, “it’s a Tom Waits lookalike contest.”

We thought ourselves superior out of habit but also, we reasoned, with cause. We both loved Tom Waits, and we were just as excited as the kid about the concert we were speeding toward, but we wouldn’t have imagined going so far as to dress like the guy. Was it cosplay or delusion? Surely he knew we were the only two to whom the mysteries had been revealed.

But then who had I pictured the audience would be made out of? Truckers on their final livers? Actual hobos from the ‘30s? You can sing all you want about Bowery bums — if you’re playing uptown, they can’t spring for tickets.

At the theater, we were incensed to discover that kid wasn’t the exception but the rule.

Even the old guys wore Tom costumes: fedoras and Cuban shoes and skinny ties. One especially dense example by the bar revealed himself only after a second glance to be Elvis Costello. Fellow lookalikes approached him for autographs. So this is what show business was: show, the careful re-creation of a slippery authenticity. Two or three years later the word hipster would be loaded with new carriage. So I had stepped away just in time, or just too late.

Once the show began, Tom was small onstage and he shouted through the first songs. He wore a bowler made of tiny mirrors, which I thought unbecoming. Cheering was compulsive and felt that way, as though there were Applause signs and points for the loudest. I was settling in for more disappointment when the lights dimmed and he sat at the piano for his solo set.

So this is what show business was: show, the careful re-creation of a slippery authenticity.

He began it with “Hang Down Your Head,” acoustic: Tom on upright piano and Greg Cohen on upright bass. All at once, the song opened up as it hadn’t before. I quit feeling critical of the dream, apart from it, and fell back into it. I was one with the song.

Tom only touched the keys as he sang — In pauses between verses the keys were quiet. Like Johnny Cash and Patsy Cline can do, he filled every word to capacity. “Hush, my love the rain now / Hush my love was so true.” I heard the trochees at the start of the lines, the spondees at the ends. Then in the chorus, everything’s stressed: “Hang down your head for me.” I’m ashamed, it says, I’m lost. Show me I still mean something to you. It’s please and sorry in the same breath.

It’s that moment of misfortune when you’re as humbled by the wrong that’s been done you as you are incensed at your betrayer. A fight with a love where you want her to be quiet and you also want to stop time, hush the clock. The one who says hush is both the betrayed and the betrayer who strays. The one who pleads hush can’t say more.

The one who says hush is both the betrayed and the betrayer who strays. The one who pleads hush can’t say more.

The act of empathy for fellow sufferers this slowed song evoked in me began in self-pity but didn’t finish there. Feeling sorry for one’s self is the mechanism by which we learn to feel sorry for others. I do you no harm because I know what harm is, how it feels. I’ll hang down my head, you hang down yours.

: : :

The doorman at the Cantab had bad lungs, so we smokers were advised to “please step outdoors.” We understood step as clamber and outdoors as the back stairway by the bar, within easy hearing of the stage. The steps wound up to an alley we never used and I was happy just to be hanging out on them with other poets in Cambridge. Vanessa was smoking Camel Reds that year but I’d wake up sore from them. Instead I’d share Dunhill’s and sips from flasks with the crowd Vanessa formed around her.

We were the hot shit that year, and we were fast becoming superior, chuckling over the bad poems, chuckling at anything. Vanessa sometimes joined the laughter, but more often remained serene, like the old woman in her poem, the one who chided hush. The rest of us, meanwhile, made fun of the way the worst of the open mic poets seemed more concerned with cataloguing their hardships than sculpting objets d’art.

We were the hot shit that year, and we were fast becoming superior, chuckling over the bad poems, chuckling at anything.

Probably, I ought to have regarded the least euphonious of the Cantab crew as the sort of writers Randall Jarrell described in Poetry and the Age, when he said, of bad print poets, “it is as if the writers had sent you their ripped-out arms and legs, with ‘This is a poem’ scrawled on them in lipstick.”

But if there’s a way to be a sophisticate and remain aesthetically egalitarian at the same time, I still haven’t found it. There’s a reason only magicians can make Shakespeare live out loud. The poets I wanted to read wrote about things that couldn’t be communicated simply, at exactly three and a half minutes in length, and onstage. My best poems were getting shorter and shorter as I pared my language down, cut out anything that seemed showy for its own sake, or that repeated itself, or that seemed too wordy. You can write a brilliant poem that’s both simple and short, but I couldn’t do it, and neither could 99 percent of the readers in Cambridge. Increasing sophistication narrows the spectrum of what we’re able to appreciate, or at least it did for me. To confirm I wasn’t misreading things, I’d read John Ashbery poems or Lyn Hejinian poems at the mic — I’d read them well — and all I saw greet them on listeners’ faces was apologetic confusion.

I’d read John Ashbery poems or Lyn Hejinian poems at the mic — I’d read them well — and all I saw greet them on listeners’ faces was apologetic confusion.

During the slam competitions (as opposed to the open mics) various audience members were deputized as scorekeepers. No special qualifications were required — democracy reigned. And in that reign it practiced every vice Polybius and Montesquieu warned us on and on it might.

: : :

The polity at the Cantab consisted of more-or-less the same audience every night; as a result, that polity developed relationships with one another and, when they were appointed judges, felt free to pursue any personal grievance that suggested itself.

More obviously, the listenership at the Cantab was generally unschooled. They didn’t read poems by people they didn’t know and they could have been a lot more critical of their own craft. Often, when a given poet didn’t have any new material to read that night, they’d read the same poem they’d read many nights before. This was encouraged as a way to perfect those poems. In all but a very few cases, I found it tedious. It reminded me of all the wrong parts of church, the parts I couldn’t stay awake through.

It reminded me of all the wrong parts of church, the parts I couldn’t stay awake through.

I did stay awake through the sex poems, mostly. Slam poetry remains the one medium outside of formal pornography in which I’ve seen the most naked expressions of human desire. There’s plenty of desire in music, of course, but it’s always more abstract. The sounds that go along with the words surround the performer and protect them, so do their instruments and the other musicians around them. The standard meter and rhyme of a pop song makes it seem less of a personal statement and more public, more of a ritual. The bodies of performers aren’t just bodies, they’re symbols.

The best songs immerse; the best slam dazzles. The simplicity, even anonymity of “Hang Down Your Head” remains with me in a way Vanessa’s “Hush,” much as I loved it then, does not. When I hear great slam I’m swept up, yes, but always with an eye on the performer. There’s a reason slam readings are judged — everyone without a scorecard is judging them too: judging the character of the reader, their looks, their right to brag or lament, the sincerity in their tone. Slam is confrontational, from reader to listener and vice versa.

Slam is confrontational, from reader to listener and vice versa.

The slam I admire doesn’t aim to comfort me. But the songs I admire do. Tom Waits, too, is just another white boy, but it doesn’t matter. I love his songs because they’re polymorphous. When a girlfriend strayed and I felt both angry and ashamed, it was “Hang Down Your Head” I played in the car. Likewise, when I began to lose my hearing — I’ll never again hear the song the way it sounded in my 20s — it was “Hang Down Your Head” that ran through me like a wound. Hush, I’d whisper to myself in loud restaurants. Hush I’d shout at the roaring tinnitus in my ears. “…the rain now … “ “ … because it takes me away … “ All I wanted was an echo of the sadness and beauty of the world, and I found it there.

Slam lives in the body, but it’s the performer’s body. You may admire them, or pity them, or desire them, but you won’t be them. When you hear a song you love, on the other hand, you’re both listener and speaker. Music has the ability, somehow, to do that. Both arts are necessary and both have their place: the one provokes empathy, the other sympathy.

I’ve grown more compassionate since 1999; a good deal of that was picked up from the hardship stories I heard at the Cantab Lounge, an apprenticeship that started in 1999 when the left side of my face was drawn with flowers, but a good deal also came from the practice of sympathy music can evoke, the spell it casts, the words and sounds that can bear your weight.

After an afternoon at a bad job lying for Silicon Valley, on my walk home through the Back Bay, the old money houses and the busy cars on Mass Ave and their Masshole horns, the word hush felt like the distillation of what I wanted the world to understand, to be for me and for anyone who needed it.